Prayagraj, Uttar Pradesh (UP): On a warm summer’s day on 14 April 2022, pastor A* was at home on the premises of Broadwell Christian Hospital in Fatehpur when he received a panicked phone call.

The call came from the 118-year-old Evangelical Church of India, located barely 500 m away in the Hariharganj locality of the eastern UP town. At the church, pastor Vijay Masih was about to finish up a daily prayer service, when all hell broke loose.

Around 55 Christians had gathered inside the church that day to commemorate Maundy Thursday—a holy Christian date to signify the last supper of Jesus Christ. The schedule for the prayer service was between 6 and 7.30 pm.

At 7 pm, around 200–250 people affiliated with the Hindu right-wing group Vishwa Hindu Parishad (VHP), stormed the church and locked the doors. Slogans against an alleged conversion at the church were raised, along with chants of “Jai Shri Ram”.

The VHP held those inside the church captive for one-and-a-half hours, before the police arrived at 9 pm, along with the local media. As a part of the initial inquiry based on the VHP’s allegations of conversion, the police asked everyone in the church to produce Aadhaar cards.

It was A who had called the police. At the scene, based on a complaint by a VHP member, the UP police booked 55 people present inside the church in a first information report at Fatehpur’s Kotwali police station.

There was no police action against the VHP.

In this concluding part of our three-part series on the misuse of the Uttar Pradesh Prohibition of Unlawful Conversion of Religion Act 2021, we explain how the Fatehpur church case has led to cases against 201 Christians in four FIRs filed over nine months—making this one of UP’s largest anti-conversion cases.

In Part 1, our investigation of 101 FIRs registered in anti-conversion allegations revealed that most complaints were filed by third parties with no legal standing, even under the state’s anti-conversion law, itself criticised for being unconstitutional.

In Part 2, our analyses of 37 bail orders by district courts in UP revealed a pattern of questionable investigation, with FIRs based on complaints by third parties, not victims but Hindu extremists.

UP’s anti-conversion law and similar ones in at least 12 states have been frequently criticised. The law has provisions that violate the Constitution, upends the burden of proof and contradicts established laws that the Supreme Court has often restated, as Article 14 reported on 14 February 2024.

Challenges to UP’s anti-conversion law and similar ones in four other states are pending in the SupremeCourt, which last heard the case in April 2023. The law “takes away the right of choice of every human being & is absolutely unconstitutional,” former SC justice Justice Deepak Gupta said in 2020.

A Pattern Is Evident

The case against the Fatehpur church set off a chain of FIRs against other Christian institutions in the town over the next nine months, including the Broadwell hospital, a Christian-run university, and a NGO.

In all instances, police reports against these institutions seem to follow the same pattern:

—There are six FIRs from “complainants” that parrot each others’ statements

—No complainant spoke of being coerced to convert to Christianity

—The police had, often, in a manner that the law does not allow, drawn conclusions based on third party complaints and anonymous complaints

—Raids on institutes resulted in little evidence of forcible conversion

As the UP police tried to build a case, the government of Prime Minister Narendra Modi of the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP), the ruling party in UP and India, acted against the finances of one these institutions.

A Flurry Of Criminal Cases

The 55 people initially named in the Fatehpur church case were accused of attempts at conversion under UP’s anti-conversion law and criminal intimidation, cheating, promoting enmity and forgery under the Indian Penal Code, 1860.

VHP sahmantri (secretary) Himanshu Dixit alleged in the first of the four FIRs that 90 “innocent Hindus” were being converted “by means of cheating… as part of the 40-day ritual”.

“The church pastor, Vijay Masih, was aided in this conversion process by the employees of the (Broadwell) hospital,” according to Dixit.

Several hospital employees attend prayer services at the church, since it is close to the hospital.

A said he could not forget the VHP invasion of their church. Nine months after the registration of the FIRs in which he was accused, his life has not returned to normal.

Between 23 January 2023 and 24 January 2023, three FIRs alleging conversion at the Evangelical Church of India were filed at Fatehpur’s Kotwali police station.

The three complainants were Fatehpur locals—Virendra Kumar, Sanjay Singh and Satyapal—who claimed they were among those present inside the church on 14 April 2022.

A was named in all the three FIRs filed in January 2023.

The case has set back the 114-year-old hospital, one of Fatehpur’s oldest. Outpatient numbers have fallen, from 125 a day to about 25-30 now.

“Our image has been tarnished and people look down upon us now,” said A.

After wild allegations in the local media, 40 employees of the Broadwell Mission Hospital, mostly Christians, quit their jobs.

The Evangelical Church was called the adda (“epicentre”) of conversion (ABP News, here), the police confiscation of religious books was reported as “proof of conversion” (Dainik Jagran, here), and a complainant’s version of events was reported without any contradicting views (Hindustan, here).

4 Christian Institutions Investigated

Along with the Fatehpur church and the Broadwell hospital, two other Christian-run institutions in UP have now been accused of running a forced conversion racket in the state.

These include World Vision India, a NGO based in Fatehpur, and the Prayagraj-based Sam Higginbottom University of Agriculture, Technology and Sciences (SHUATS).

All four have been mired in legal cases filed under UP’s anti-conversion law.

An Article 14 analysis of the FIRs in the Fatehpur church case revealed a copy-paste model of accusations, where complainants spoke of a conversion model known as “Mission UP”.

Here’s what we found:

—All three FIRs were identical in terms of language and use of specific phrases

—The allegations of all three complainants tally with each other

—All three claim to have been “coerced to undergo conversion” by a female nurse employed at the Broadwell hospital named Lilly C

—Sanjay Singh first mentions the phrase “Mission UP”—supposedly a state-wide conspiracy to forcibly convert people to Christianity. All three complainants named pastor A as one of the chief proponents of the programme

—All three complainants alleged that “foreign funds” were being received by the Christian institutions mentioned for the conversion “task”

On 21 February 2023, the UP police set up a special investigation team (SIT) to look into each of these complaints. It was led by Fatehpur deputy superintendent of police (DSP) Veer Singh.

Article 14 accessed the 700-page SIT chargesheet submitted to the Fatehpur chief judicial magistrate in the case related to one of the FIRs (FIR no. 55, the second FIR filed on 23 January 2023), as we examined the evidence gathered by the police.

The trial in this case is going on, with those named in these FIRs required to attend court as part of monthly hearings.

Conversion Conspiracy: Broadwell Hospital

Founded in 1894, the Broadwell Christian Hospital began in Cincinnati in the US.

The Fatehpur branch, established in 1906, is now 118 years old. In 1973, the hospital’s management was handed over to New Delhi’s Emmanuel Hospital Association. Part of a network of 19 hospitals under the association, the hospital’s community health programme catered to rural areas during the COVID-19 pandemic.

A, 51, has been employed at the hospital since 2010. He sang as part of a choir and held daily prayers at the hospital. It was A who informed the police about the VHP locking up people inside the church on 14 April 2022.

“That day, the police had arrested women and children, some as young as one or two years old and had taken them to the police station,” A told Article 14.

In October 2022, the Fatehpur police began visiting the hospital frequently.

“They asked for documents, including land records,” said A, who lives on the hospital campus. “We provided them with all relevant documents, including papers related to charity work.”

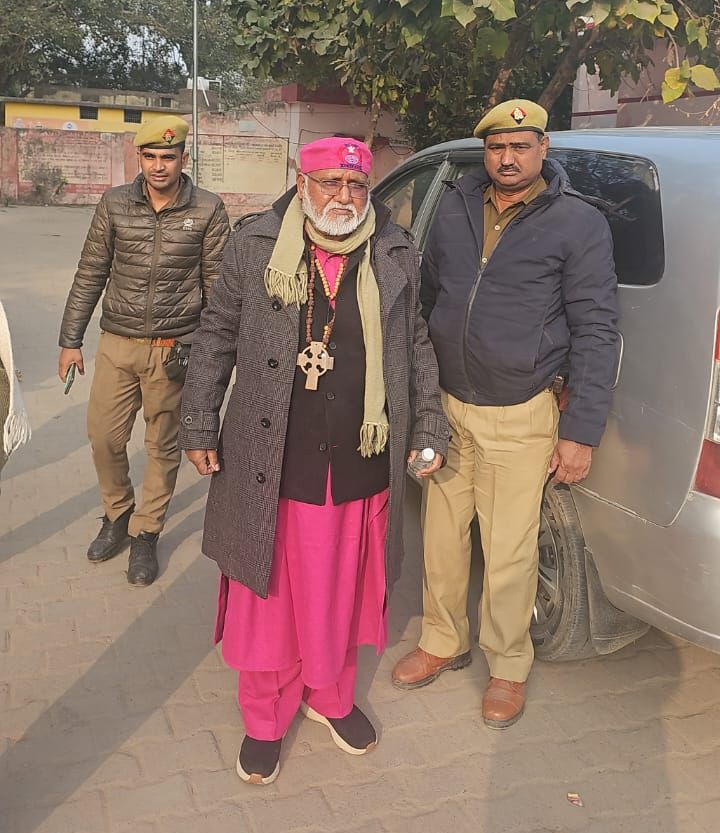

On 18 January 2023, 30 police personnel raided the hospital and arrested 58 hospital staffers, including A. Two days later, on 20 January 2023, A found out that he had been named in a conversion-related FIR.

Article 14 sought comment from Fatehpur deputy superintendent of police Veer Singh, who is also the SIT’s investigating officer, calling and sending him WhatsApp messages, and an email questionnaire to the station house officer of the Kotwali police station in Fatehpur, but there was no response.

We also called and sent messages seeking comments from UP director general of police Prashant Kumar.

There was no response from any of the three officers. We will update this story if they respond.

‘I Spent 140 Days In Jail’

“I spent 140 days in jail,” said A, among the few staffers still working at the hospital. “My wife still breaks down thinking about the toll this case took on us and the money we had to spend.”

The SIT chargesheet comprises two statements by the complainant Sanjay Singh, both recorded by the police in February 2023.

Such statements have little evidentiary value, said experts, since these are recorded while a person is in police custody and are usually aimed at building the prosecution’s case.

“It is a well-established fact and law that statements that are given before the police officer under section 161 (allows the police to examine witnesses and record statements) of the CrPC (Criminal Procedure Code) are not admissible in court,” said advocate Areeb Uddin Ahmed, who practises at the Allahabad High Court.

Unless these statements are recorded before a magistrate, they remain allegations, Ahmed said.

“If the victim has said that he or she has been lured, what is the reason for doubting a police statement?” asked Yashovardhan Azad, a retired Indian Police Service (IPS) officer and former special director of the Intelligence Bureau.

With respect to the inclusion of statements under section 161 of the CrPC, Azad cautioned:”There has to be proof that something had passed hands.”

Sanjay Singh told the SIT that in January 2022, he was approached by auxiliary nurse and midwife Lilly C from the Broadwell hospital, along with SD Rao, manager at the NGO World Vision India, to “leave Hinduism and embrace Christianity”.

In his complaint, Sanjay Singh alleged that he was promised “cash and gifts” by Lilly and Rao, with the promise of “free education (for his children) at the mission school, along with free treatment at the Broadwell hospital”.

There is no other proof in the chargesheet to substantiate conversion claims, or of a conversion model named “Mission UP”.

“We were told to propagate Mission UP so that every individual in Uttar Pradesh becomes a disciple of Jesus, since Hinduism and other religions are based on falsehood and hypocrisy,” Sanjay Singh wrote in his statement.

“As a preacher (sic) of Mission UP, we were told to visit villages and convince locals to convert, including pregnant women, by telling them about the free treatment at the Broadwell hospital.”

Identical Complaints

The other two complainants—Virendra Kumar and Satyapal—submitted almost identical statements as Sanjay Singh.

All three told the police about their original Aadhaar card “being taken away”. They were promised a new Aadhaar “with a Christian surname”. They claimed that their names were changed to Sanjay Albert Francis, Virendra D’Souza and Satyapal Samson.

Sanjay Singh refused to comment. The other two complainants were not reachable.

Since the trial is underway, the Broadwell hospital refused to comment.

Dr Sujith Varghese Thomas, who served as a senior administrative officer at the Fatehpur branch of the hospital from 2008 to 2019, said he had been called in 2023 from Coonoor in Tamil Nadu, where he is now posted, to manage the crisis at the Fatehpur hospital.

“We have never been involved in conversion, that’s not our goal,” said Thomas. “As part of a charitable institution, members from our team would reach out to locals in villages regarding treatment.”

Thomas said public health initiatives by the hospital’s community health department were “appreciated by the administration, including the local CMO (chief medical officer)”.

In 2018, a crowd led by VHP members had roughed up individuals inside the church. According to Thomas, church authorities submitted a complaint to police.

“We don’t know whether that complaint was converted into an FIR or not,” said Thomas, who added that Himanshu Dixit was part of the 2018 crowd. “He would visit our hospital for treatment.”

Conversion Conspiracy: Evangelical Church of India

The only plausible evidence connecting Fatehpur’s Evangelical Church of India with the alleged conversions are statements by shopkeepers around the church’s locality—individuals who have not been named in the chargesheet.

Based on these statements, the police arrested pastor Masih twice. He was first arrested on 14 April 2022, the day the VHP broke into the church, and released on bail two days later.

Masih was arrested again on 30 October 2022 and incarcerated till 14 June 2023. He was named in the three FIRs registered by the Fatehpur police in January 2023.

In the daily diary note at Fatehpur’s Kotwali police station dated 24 February 2023, the investigation officer mentions “protests against conversion” from “a year ago”, referring to 2022. No one who alleged such conversion is named, citing the “influential” status of the Christian community.

On the basis of these anonymous statements, the SIT concluded that the accused were indeed involved in “mass conversion of Hindus” at the Fatehpur church.

The SIT also concluded that the motive for such large-scale conversions was to let “Christianity… emerge as the most powerful religion in the state”.

In October 2023, in the Article 14 study of 101 FIRs previously quoted, we revealed how 62% (63 of 101) of FIRs were filed in response to complaints by third parties (other than the accused or victim), including Hindutva outfits such as the VHP, the Bajrang Dal and the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh (RSS).

In February 2023, the Allahabad high court observed that Himanshu Dixit, the VHP office-bearer, “was not a competent person to lodge an FIR in the Fatehpur mass religious conversion case”.

Section 4 of UP’s anti-conversion law says that “any aggrieved person, his/her parents, brother, sister or any other person who is related to him/her by blood, marriage or adoption may lodge a first information report of such conversion”.

Dixit was a “third party”.

“I had information from some relatives of Hindus regarding mass conversion to Christianity,” Dixit told the SIT, which acted on his statement.

As for the three other complaints filed in January 2023, Masih said, “We didn’t know these persons, nor had they visited the church before.”

For Masih, there has been no closure even after he was released from jail.

“Since local media reports had labelled me as the mastermind of conversions in Fatehpur, locals stopped visiting the church,” said Masih. “I’m also fearful of being implicated in more cases, so I no longer frequent the church.”

‘A Job, Money & A Beautiful Girl’

Following the allegations of conversion against the Fatehpur church and hospital, the Prayagraj institution at the eye of the storm is the Sam Higginbottom University of Agriculture, Technology and Sciences (SHUATS), in the UP town of Naini, 130 km southeast of Fatehpur.

Established in 1910 by an American missionary, the Christian minority institution received deemed university status in 2000, when the BJP’s Murli Manohar Joshi was union minister of human resources.

Since January 2023, SHUATS has been mired in legal cases in connection with alleged forced conversions and sexual assault.

The UP police first issued notice to SHUATS officials in December 2022, asking them to “explain their role in the mass conversion” reported in Fatehpur in April 2022.

On 20 January 2023, SHUATS vice-chancellor R B Lal and director Vinod B Lal were booked in a forced conversion case on the basis of a FIR filed by Sarvendra Vikram Singh, a former student of the university, at Fatehpur’s Kotwali police station.

Singh alleged that the vice-chancellor promised him “a job, money and marriage to a beautiful girl” if he converted to Christianity.

On 4 September 2023, a former woman employee of the institute alleged sexual assault and forced conversion against R B Lal, director Vinod B Lal, former supervisor Mohammed Rizwan, pastor Rajkaran and three unnamed persons.

R B Lal has had 16 cases filed against him between 1998 and 2021. In November 2023, another FIR alleging gang-rape and conversion was filed against him in UP’s Hamirpur district.

In 2007-08, SHUATS was embroiled in a controversy with a number of students alleging that the university was handing out fake degrees.

The ‘Court Of Jesus’

On 12 March 2023, a police special investigation team, led by Fatehpur deputy superintendent of police Veer Singh raided SHUATS.

The chargesheet it submitted hinges on the recovery of documents and CDs from the university premises and a printer and a scanner, allegedly used to print fake Aadhaar cards.

Charlie Prakash, a Prayagraj-based advocate handling the cases filed against SHUATS, alleged the FIRs were “problematic”.

“The original FIR in this matter was filed by someone who is technically not an aggrieved person,” said Prakash. “In a year’s time, the police have filed multiple FIRs on behalf of others that are now claiming to be victims.”

“This seems like an effort to help sustain the initial complaint,” said Prakash.

A religious congregation on the SHUATS campus, referred to as “Yeshu ka Darbar (court of Jesus)”, caught the attention of the UP police.

Meant for prayers and sermons and held regularly on campus, “Yeshu ka Darbar” is a well-documented public event, with regular videos and vlogs and no indication of forced conversions.

All the three complainants of the Fatehpur FIRs—Virendra Kumar, Sanjay Singh and Satyapal—said in their January 2023 complaints that they were told about “taking a bath at Yeshu ka Darbar inside SHUATS campus”, meant to “purify” them as part of a conversion ritual.

Several old CDs of these congregations were picked up by the SIT during its March 2023 raid. To lend credence to the conversion theory, snippets from old CDs of Yeshu Darbar, (held prior to the enforcement of UP’s conversion law in 2020) were included in the SIT chargesheet against the university.

A Law Applied Retrospectively

The snippet of a “Yeshu ka Darbar” held on 24 July 2016 finds mention in the chargesheet. “Between 8 minute and 36 seconds to 18 minute and 31 seconds, accused R B Lal (vice-chancellor) along with his wife Sudha Lal are addressing people at Yeshu ka Darbar and rechristening their names as per Christianity,” wrote an investigating officer.

The SIT draws a similar conclusion in reference to a “Yeshu ka Darbar”organised on 24 March 2019, where the child of a kesarwani caste couple was “blessed” by R B Lal.

Prakash said the anti-conversion law could not be applied retrospectively. He referred to R B Lal as a “spiritual leader”, adding that many families visited him, seeking blessings for their children. Such acts, said Prakash, “do not signify forced conversion”.

“Every community has its practice of carrying out charitable initiatives,” said advocate Azizullah Khan, who practises at the Allahabad high court, “These cannot be seen with the lens of criminality.”

“These (Yeshu ka Darbar) were weekly congregations that began on Friday evenings and went on till Sunday,” an assistant professor at SHUATS told Article 14, “Items like blankets were distributed at these events, along with money ranging from Rs 50-100.” The professor is associated with the union of teachers and staff members protesting against the management.

There were no indications of conversions at these congregations.

“How will it be established that distribution of items amounts to allurement or results in gratification?” said Khan. “There will have to be supporting evidence that forced conversions were indeed carried out.”

For around 1,300 current employees of SHUATS, including teaching and non-teaching staff, conversion cases against the institution have delayed salaries since 2019.

Ajay Singh, 52, an assistant professor employed at the university since 2005, has already written a letter to Prayagraj district magistrate Navneet Singh Chahal on 5 January 2024, seeking a probe into delay in payment of salaries. He now plans to write to UP chief minister Yogi Adityanath.

Conversion Conspiracy: World Vision

On its official website, the Christian NGO World Vision India, describes its work on “empowering vulnerable children and communities living in the context of poverty and injustice”.

On 21 February 2024, the union government cancelled the permission granted to World Vision to receive foreign contributions under the Foreign Contribution Regulation Act (FCRA) 2010.

The SIT chargesheet against the NGO primarily comprises statements by locals from rural Fatehpur. Most of these have been recorded under sec 161 of the CrPC, meaning they cannot be used as evidence unless confirmed by a magistrate.

On 2 March 2023, Deepak Kumar, a resident of Hasimpur village, was quoted as saying that representatives of World Vision India had visited in 2022 and offered “Rs 35,000 to anyone willing to leave Hinduism and embrace Christianity.”

Kumar alleged he was promised free treatment at the Broadwell hospital and free education at SHUATS if he converted—exactly like Sanjay Singh, Virendra Kumar and Satyapal, the three complainants against the Fatehpur church.

In an almost identical statement, another resident of Fatehpur’s Thariyaon village, Satish Chandra Srivastava, told the SIT that he “didn’t know the names of volunteers (who spoke about conversion) but can recognize them (if produced)”.

Locals said among the things World Vision gave them were a bar of soap, a mosquito net, goods required to set up a gumti (kiosk), biscuits and a tin drum to store foodgrain.

“Merely receiving eatables or household stuff from an NGO cannot be a sole reason or objective behind conversion,” said advocate Ahmed.

Referring to an individual’s right, under part 3 of the Indian Constitution (to freely profess, practise and propagate any religion), Ahmed said, “The anti-conversion law is only applicable to forced conversions, not consensual conversion.”

On the issue of whether such distribution of items would comprise a “quid pro quo”, former IPS officer Azad said, “As an investigation officer, if I find that a kiosk has been transferred by an NGO, I would certainly include it in the probe.”

But this could be done, Azad explained, “provided there are exact dates of meetings and the NGO has maintained record of such meetings”.

The SIT recorded such statements from 47 “labharthi”s (or beneficiaries) of the alleged conversions—locals who the police believed were “from Hindu religion and were offered allurement” by the representatives of World Vision India.

None of the labharthis said they were forced to convert to Christianity.

Yet, the SIT uses these vague statements, third party complaints and has little evidence that the four Christian-run institutions were forcibly converting locals to Christianity.

Prakash, counsel for the four institutions, said that the Christian community was being “targeted” by UP’s BJP government—“just like Muslims were targeted when (chief minister) Yogi (Adityanath) came to power in 2017”.

* Name withheld on request

(Akanksha Kumar is a Delhi-based multimedia journalist.)

Get exclusive access to new databases, expert analyses, weekly newsletters, book excerpts and new ideas on democracy, law and society in India. Subscribe to Article 14.