Daman (Daman & Diu): Hansa Ganesh Tandel was taking her morning medicines when neighbours told her that “JCBs” were coming to demolish their homes. It was 7:30 am on 3 February 2023, and as she rushed out of her one-room, concrete home with her husband and son, she could hear the unmistakable roar of backhoe excavators making their way towards her.

When the JCBs—used as a generic name after India’s largest-selling excavators—arrived, Hansa wept but could do little to convince officials to halt the demolition. They soon got to work, tearing down the walls of her home with most of her belongings still inside.

“We had lived in these houses since 1971, and one fine day the administration came and demolished them,” said Hansa Tandel, a stocky, saree-clad fisherwoman in her late 50s, weeping as she described the trauma of seeing her home of 20 years reduced to rubble in a few hours.

“We sold fish every day to save up to build that house, and suddenly it was gone,” she said. “We have nothing left. Hume road par le aaye hai (they’ve left us on the road).”

Raised with six brothers in a family of native fisherfolk, Hansa wistfully recalled a childhood running along the white sand beaches of the former Portuguese colony of Daman. She lived all her life in Master Sheri, next to Daman’s newly reconstructed 5.45-km-long, coastal promenade—named Namo Path after Prime Minister Narendra Modi—overlooking the Arabian Sea.

Hansa Tandel’s now-demolished home was, like most houses in Master Sheri—one of 18 sheris or localities in Daman—once a rough hut, transformed by her and her husband to a colourfully painted concrete house of one or two bedrooms, harking to an era of housing rarely seen across urban landscapes today but which continue house native fisherfolk.

When the JCBs had done their jobs, 16 homes in Master Sheri were demolished on the orders and supervision of officials from the office of the collector and Daman’s district magistrate. More than 80 people, including Hansa Tandel, found themselves homeless.

“It was our home,” said Hansa Tandel. “They should at least have thought about where we could go after the demolitions.”

The demolitions of houses in Daman’s Master Sheri follow a series of forced evictions and home-demolitions in states governed by the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP), such as in Madhya Pradesh, Gujarat, Uttarakhand, Uttar Pradesh, and Haryana, or indirectly controlled, as in New Delhi, the majority of homes and properties demolished belonging to Muslims and other minorities.

In the first four months of 2023, the administrator of the union territory of Dadra & Nagar Haveli and Daman & Diu ordered two demolition drives, in Master Sheri and a neighbourhood called Mitnawad to clear houses deemed to be ‘illegal encroachments’ on government land. There were no minorities involved, but officials mentioned that most of the homes belonged to “outsiders”. Those evicted said they belonged to traditional Damanese fisherfolk communities.

The union territory does not have an elected government, but the administrator, Praful Khoda Patel, is a close associate of Modi. Patel is also the administrator of the Muslim-majority Lakshadweep Islands, also administered directly by New Delhi and where he has generated local resentment by trying to change or otherwise disrupt local life, as Article 14 reported in 2021 and 2022.

In Daman, where about 59,000 people—90% Hindu, 8% Muslim and 1.5% Christian—live over 79 sq km, locals contend that all the alleged encroachments are homes that were previously “regularised” or granted official status by the State, directly or otherwise.

The local administration, for instance, gave homes in Master Sheri house numbers, electricity connections and water lines. Residents paid property taxes for several decades. In Mitnawad, six homes, either demolished or given eviction notice, were built with monetary assistance from the Prime Minister’s flagship housing programme.

Even though residents provided officials with property tax receipts, electricity and water bills, officials backed by local police rolled in with a cavalcade of backhoe excavators and trucks and demolished their homes.

No Evidence Of Due Process

Hemaxi Tandel’s home was one of the 16 demolished on 3 February 2023 in Master Sheri. She and her father, Bhagwanbhai, an unshaven, silver-haired septuagenarian, weakened by a decade-long paralysis to the left side of his body, were distraught when we met them.

She and her father now rent a house for Rs 3,000 a month, less than 100 m from where their former home of about 20 years stood. Bhagwanbhai spends most of his day on a small bed near the front door, requiring help with most daily activities.

“I was alone, I didn’t understand what to do, I kept crying,” said Hemaxi Tandel, 40, who is unemployed, weeping as she spoke of the day the machines came. She tried to frantically pull out what she could before the excavators flattened their home, but she lost clothes, utensils, her father’s medicines and furniture.

Many said that officials gave them only a few minutes to remove belongings and vacate their homes, before the excavators tore down their houses, as they watched in shock, anger and sorrow, the demolitions in obvious violation of court rulings.

The demolitions disregard a landmark Supreme Court judgement in 1985, which ruled that evictions and demolitions must: follow clear rules and procedures; include “meaningful” consultation; be “fair, just and reasonable”; and be “consistent with rights of life and dignity”.

In Sudama Singh & others vs Government Of Delhi 2010, the Delhi high court held that before any eviction, it was the duty of the State to survey all those facing evictions and to draft a rehabilitation plan in consultation with the “persons at risk”.

While notices had been served, there was no evidence of any rehabilitation of any of the displaced residents of Master Sheri, where most residents were vendors, blue-collar workers or fishermen, living life on the margins with few savings. Most said they were particularly struck by the unyielding nature of the officials who carried out the demolitions.

‘They Didn’t Even Let Us Take Our Fan’

Pushpa Devi, a 30-year-old mother of three, now rents a home opposite Hemaxi Tandel’s. She described how they lost most belongings when their house was brought down within a couple of hours.

“They didn’t even let us take our fan out,” said Pushpa Devi, crying. “These days, because of the heat, we have to sleep outside.” She clasped her back as she spoke, visibly discomfited by her pregnancy and the unforgiving coastal humidity of Daman.

With two girls aged 13 and 9, a boy aged 12, and another child expected, Pushpa Devi and husband, a paani-puri vendor, struggle to pay rent and other bills. She said she was going to pull her children out of school.

“The difference between the need of an animal and a human being for shelter has to be kept in view,” the Supreme Court said in Shantistar Builders vs Narayan Khimalal Totame 1990. “For the animal, it is the bare protection of the body, for a human being it has to be a suitable accommodation which would allow him to grow in every aspect—physical, mental and intellectual.”

The Supreme Court held that the right to life encompasses other rights.

"The right to life would take within its sweep the right to food, the right to clothing, the right to a decent environment and a reasonable accommodation to live in,” said the Supreme Court.

An official of the Daman collectorate, speaking on condition of anonymity because he was not authorised to speak to the media, said the demolitions were “part of the routine process of the administration in clearing illegal encroachments”. Most of those whose houses were demolished were not originally from Daman, he claimed, but were immigrants “living here in rented homes”.

Since the demolitions of 16 Master Sheri houses, no construction is evident and no plans have been revealed for what officials claimed was government land. Piles of rubble and the ruins of former homes remain.

For the displaced Damanese, the obiter dictum of the judiciary in Shantistar Builders offers little solace, if any.

Daman’s Complicated Land Tenure Regime

The Master Sheri demolitions were a consequence of eviction notices served to the 16 (now demolished) houses on 13 December 2022, by the deputy collector of Daman under section 40(2) of the Goa, Daman & Diu Land Revenue Code, 1968

The notices said the homes were “encroachments on government lands” and each notice asked residents to “show cause” why the “encroachment…should not be removed” within seven days, “failing which the government will take action to remove the encroachment at (the recipient’s) own risk and cost without any further notice”.

On behalf of the locals, a lawyer called Subhash Rakshe filed suit in January 2023, contesting these notices. The district judge of Daman refused to stay the eviction notices, leading to the demolitions of Master Sheri homes in February 2023.

An outspoken man with a fiery temper and a handlebar moustache, Rakshe was agitated, as he spoke to us across a table in his cramped chambers a few km from the demolished houses. “All the lands in Daman do not belong to the government!” shouted Rakshe, “These lands are gamdhani lands, and they belong to the people of Daman.”

Daman was liberated by the Indian State on 19 December 1961 from Portuguese colonisers, whose land-tenure system vested village land with a “village proprietor” or gamdhani, who either bought village land or received it as a gift from the colonial government.

Gamdhanis would then grant land, usually fields, to farmers or other occupants. After the liberation of all former Indian Portuguese colonies in December 1961, the Indian State enacted the Daman (Abolition of Proprietorship of Villages) Regulation, 1962, which, among other things, abolished ‘the proprietorship of villages in the Daman District’, and transferred all land rights to the union government.

However, relying on the interpretation of these regulations provided by the Supreme Court in Gulabbhai Vallabbhai Desai vs Union of India in 1967, Rakshe argued before the Daman district court that “property which was with the gamdhani, within the limits of Daman Municipal Council, after the abolition of proprietorship, was not vested with the Central Government”.

Rakshe quoted the Supreme Court order: “The Writ Petition 216 of 1963 will, therefore, be dismissed with the declaration that the Municipal area does not vest with the Government under the Regulation…”

Rakshe was confident in January 2023 of winning the case and had even informed the locals that demolitions were unlikely, given the Supreme Court’s clear orders.

‘We Had Even Printed Her Wedding Cards’

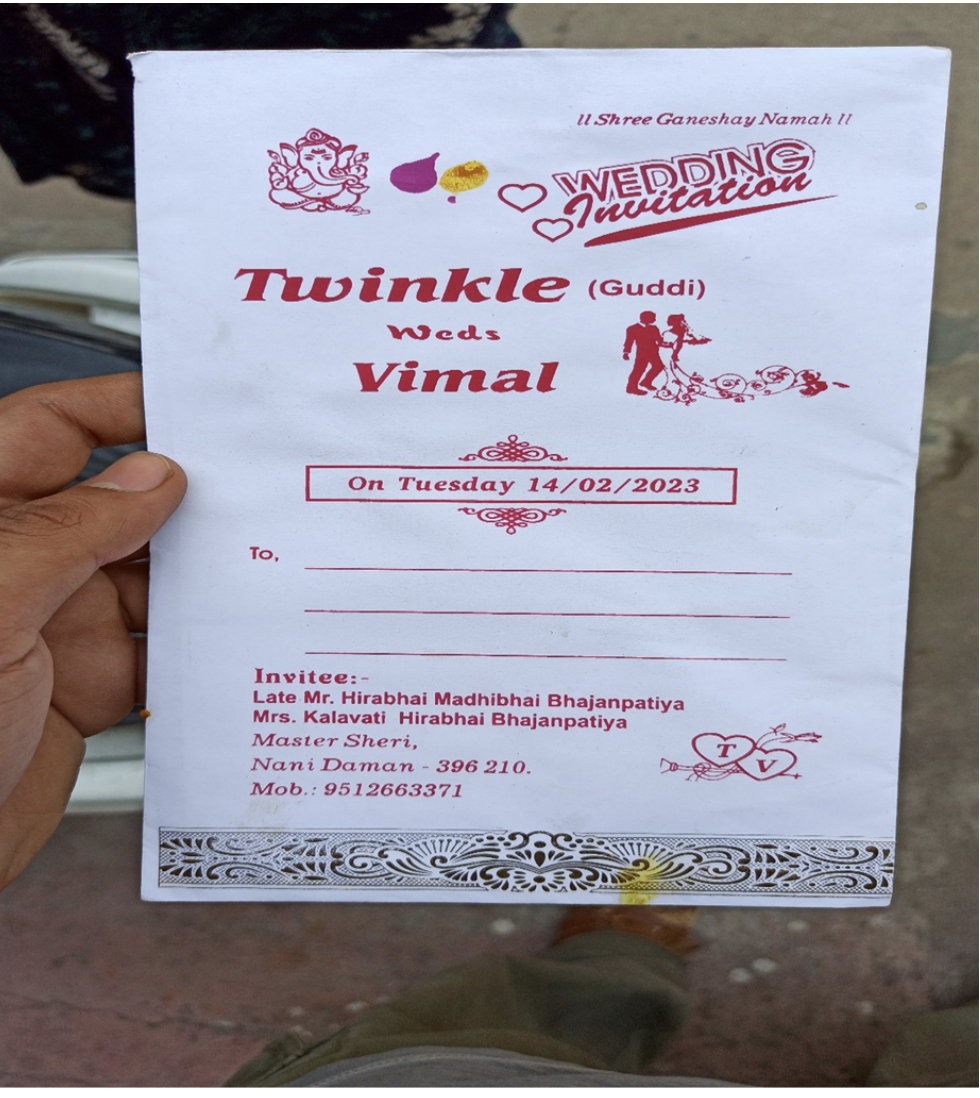

It was on Rakshe’s assurance that Poonam Chand Adi of Master Sheri planned the wedding of his niece Twinkle.

“[Rakshe] said they wouldn’t demolish our house and said that Twinkle’s wedding will happen,” said Adi. “Accordingly, we scheduled the wedding for 14 February. We had even printed her wedding cards. But early morning on 3 February, they arrived with their JCBs.”

Adi, more than 6’-6” tall and normally confident, recalled how the arrival of the administration’s cavalcade triggered debilitating worries about the health of his sister Kalavati. “I was afraid for my sister, Twinkle’s mother,” he said. “I was afraid that she would have another heart attack. She’s already had two.”

Adi recalled how he pleaded with officials to postpone demolitions until after his niece’s wedding, how he called and appealed to the collector of Daman for temporary clemency, but failed to get any sympathy from the administrator of Daman, Patel.

“The collector agreed with me, and called up Praful Patel right there to postpone the demolition,” said Adi. “The collector put the call on speakerphone. On the speaker, as we were all gathered around the Collector, we heard Praful Patel shout at him, telling him to ‘do the job you’ve been told to do’. There was nothing we could do after that.”

Article 14 sought comment from the office of the collector, Saurabh Mishra, over email on 6 September 2023 about this account. This story will be updated if he responds.

Patel, The Unelected Administrator of Daman

Daman, part of the union territory of Dadra & Nagar Haveli and Daman & Diu, as we said, does not have a legislative assembly and is governed by an administrator appointed by the President of India, meaning the union government.

This means important departments, such as land and the police in Daman, are controlled by the union government. The Damanese have no say in electing their representatives and rely on the favour and good judgement of whoever New Delhi appoints as administrator, which has been Patel since August 2016.

A former BJP member of the legislative assembly of Gujarat, Patel served as a minister of state for home between 2010 to 2012 in state government, then headed by Modi as chief minister.

On 26 January 2020, Patel’s brief was expanded from Daman to the first administrator of the newly created union territory of Dadra and Nagar Haveli and Daman and Diu after the merger of Dadra and Nagar Haveli with Daman and Diu, which was previously attached to Goa.

Patel also took charge as administrator of the union territory of Lakshadweep Island on 5 December 2020, indicating the trust that Modi reposed in him.

Locals said Patel’s tenure as administrator of Daman has been marred with controversy over land rights, with his attitude described as ‘hard-to-reach’ at best and ‘dictatorial’ at worst.

For example, in December 2018, eviction notices, similar to those issued to Master Sheri residents, were served on locals living along the seafront of the Moti Daman area of Daman, ending in house demolitions in November 2019 and the detention of 70 protestors, with a criminal suit against several of them pending in the sessions court of Daman. They are accused, among other charges, of unlawful assembly.

None of the protesters, out on bail since 2019, were willing to comment, fearing persecution from the Daman administration. On 22 November 2022, a tribal man named Jayenti Baraf in Silvassa, headquarters of Dadra and Nagar Haveli district, self-immolated on the first floor of his home, which the administration wanted to take over against his wishes, as he repeatedly rejected compensation.

More recently in November 2022, Patel’s plan to demolish a 400-year-old Catholic chapel and build a football field there became public, drawing criticism not only from local Catholics but the Damanese in general, who view the chapel as a heritage site.

Patel’s bio on the union territory’s official website says he has paved the way “for world-class projects while also showing sensitivity to people’s various needs, particularly those of the marginalized sections”. The former residents of Master Sheri said they only remembered his dedication to destroying their homes.

Article 14 sought comment from Patel over an email sent to his office on 5 September and followed up with a phone call on 6 September. There was no response to the email. Patel’s office said over the phone that he was not in Daman, and it was uncertain when he would return. We will update this story if he responds.

PM’s Programme Housing Declared ‘Illegal Encroachments’

A few kilometres from Master Sheri is Mitnawad, a settlement primarily housing the Mitna community—officially designated an OBC or other backward caste—where the Daman deputy collector served 59 houses with eviction notices on 20 February 2023.

A representative of the local municipal body, speaking on condition of anonymity, criticised “arbitrary administrative action”: six of the 59 houses scheduled for demolition were partially funded and built in November 2022 under the Pradhan Manti Awas Yojana (PMAY) or the Prime Minister’s Housing Programme.

Pravinaben Mitna, one of six Mitnawad PMAY beneficiaries served eviction notices on 20 February, said she was ordered to vacate the land within 15 days. Her house, less than a year old, is home to herself, her husband Kapil, a private electricity company worker, his elderly aunt and their two school-going children.

The notice said her home was an “encroachment” on government land and that she was liable “to pay a penalty of two times the assessment of rent for the land for the period of unauthorized use or occupation”, an amount not levied on the Master Sheri victims.

“The DMC (Daman Municipal Council) has given us completion certificates after inspecting the house construction,” said Kapil Mitna. “Now, how can they say it’s illegal?”

“We even have government-painted PMAY name plates on the front wall of the house,” said Kapil Mitna. “If we can't be allowed to live in a ‘Pradhan Mantri’ built house, where can we stay?”

High Court Stay After Walls Are Torn Down

On 13 March 2023, Pravinaben Mitna and the five other PMAY ‘beneficiaries’ were served another “show cause notice”, this time from the DMC, ordering them to reimburse PMAY payments of Rs 279,000 to the municipal body.

“First, they want to break our homes, now they want us to pay for it?” said Kapil Mitna. “Where will I get the money from?”

Article 14 sought comment from DMC’s chief officer, Arun Gupta, under whose name the notices were served. He was later transferred. On 6 September, we sought comment from Sanjam Singh, the new chief officer, over email and telephone. There was no response. We will update this story if there is one.

On 20 February, the 6 PMAY beneficiaries moved the Bombay High Court challenging the notices. On 6 April, a division bench of Justice Neela Gokhale and Justice G S Patel stayed any demolitions, but the order came two days after a single JCB had torn down street-facing walls of Pravinaben Mitna’s home, leaving it uninhabitable. Government officials sealed the other five PMAY houses.

On 12 June 2023, the union government issued a press release saying that “PMAY(U) has transformed the lives of the poor by providing affordable housing, improving living conditions, and empowering women”.

Pravinaben Mitna and her family now live in rented accommodation close to Mitnawad. Like Pushpa Devi, Pravinaben and Kapil said they could not afford to pay for their children’s education and rent.

On 18 July 2023, the Bombay High Court extended the interim stay on further demolitions of the PMAY houses until 13 September 2023. On the day of the demolitions, officials told Mitnawad locals that the land would be used to build a police headquarters and a playground for children.

(Maitreya Prithwiraj Ghorpade is a freelance reporter with Land Conflict Watch and an independent environmental lawyer.)

Get exclusive access to new databases, expert analyses, weekly newsletters, book excerpts and new ideas on democracy, law and society in India. Subscribe to Article 14.