New Delhi: This year, the Bharatiya Janata Party-led Union government has consistently denied maintaining any centralised records of the number of Internet shutdowns in the country.

These denials, issued at least twice in Parliament, come despite the Internet being suspended in regions like Jammu and Kashmir, West Bengal, Assam and Rajasthan for long durations.

The government states that the Temporary Suspension of Telecom Services Rules, 2017, which enables them as well as state governments to shut the Internet, does not mandate them to maintain a record of such blockades, according to an answer to a question by Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) member of Parliament Varun Gandhi in the Lok Sabha on 9 February 2022.

But researchers and digital rights advocacy groups have found that such instances have only grown over the past 10 years, earning India the tag of being the “Internet shutdown capital of the world”.

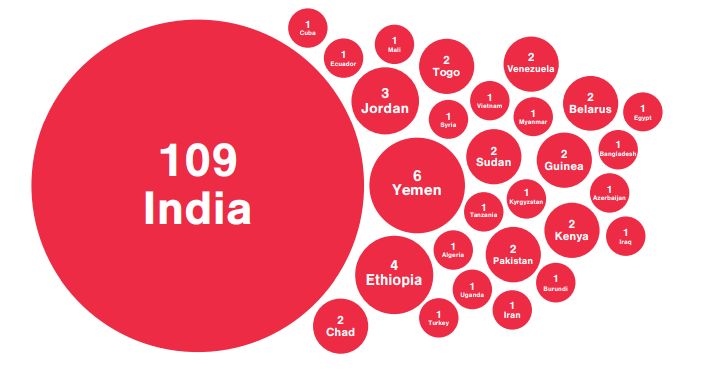

India accounts for over 70% of the world’s Internet shutdowns in 2020. The frequency of this kind of censorship appears to be increasing despite the soaring number of active Internet users in the country.

Now, a new report authored by the Centre for Human Rights of the American Bar Association, a voluntary bar association of lawyers in the US, paints a rather damning picture on the impact of such suspensions on human rights defenders in the country.

Internet blockades have made it harder for the media to function, for courts to continue their duties and for activists to mobilise or expose human rights violations, according to the report.

The report found that internet shutdowns, which were once only a feature in Jammu and Kashmir, have extended to other Indian states to deal with communal tensions and protests. It noted that the number of Internet suspensions ordered have grown between 2012 and 2021, with the most number of incidents recorded in 2020, the year India went into a nationwide lockdown as the pandemic struck.

It has turned into an “often-used tool the government relies upon to silence dissent and limit the rights to freedom of press and expression under the guise of maintaining law and order”, said the report.

Over the past few years, the judiciary has intervened to curb internet suspensions. In response to Kashmir Times editor Anuradha Bhasin’s petition, the Supreme Court in 2020 directed the union and state governments to publish internet shutdown orders on official government websites and periodically review them as well.

Currently, the Gauhati High Court is hearing a public interest litigation by Ajit Kumar Bhuyan, the editor of Prag News, an Assamese news channel, challenging the constitutional validity of the Temporary Suspension of Telecom Services Rules 2017.

Notably, the report stated that “without the Internet, journalists and civil society actors were unable to report on any human rights abuses that took place during protests and on the physical lockdown of Kashmir by both state and non-state actors.”

Researchers on digital rights in India have found it rather bizarre that the government has strayed away from keeping a track on Internet blockades given the push to digitise the country through initiatives like “Digital India”.

“Perhaps they do not want to do this [maintain records] because it may have ramifications for their image internationally,” said Krishnesh Bapat, a lawyer and associate litigation counsel at Internet Freedom Foundation, a digital rights advocacy organisation.

In The Dark

The longest Internet shutdown in India was imposed in 2019 when the BJP-led Centre stripped Jammu and Kashmir’s autonomy, downgrading its status to a union territory. Before the change was made, a strict curfew was in place, with a military build up and landlines and broadband services were stopped.

Residents in the region could not access online banking services, government filings and it severely limited the ability of activists to function, according to the report by the Centre for Human Rights of the American Bar Association.

The report is based on publicly available material, such as news reports, and interviews with 25 human rights defenders in 11 states nationwide. The researchers of this report did not wish to be identified because of “security mitigation”, according to an official at the American Bar Association who did not wish to be identified as well.

The report revealed that activists were unable to track some residents detained during the clampdown as they were shifted from Kashmir to prisons in Uttar Pradesh, where some still remain. “Many detained activists lack political connections and they may die in prison, where their stories die with them,” it said.

Residents of the region were only able to access a phone if they were connected to a “high-ranking official”. Even then the anxiety of being in a blackout continued for many, the report stated.

“Given the high level of risk, the threat of detention and/or physical surveillance, and the fear of online communications being monitored, people were ‘paranoid’ and did not feel comfortable speaking on the phone,” said the report.

Impact On The Media

The impact of this blockade on the media was even more severe, according to the report. Of the 55 dailies in Kashmir, only four managed to publish an issue on August 6, 2019, the day after the abrogation of Article 370, that granted the region its autonomy.

The report mentioned that absence of the internet caused both “direct and indirect censorship” as the curfew made it difficult for people to reach offices and the reporters were unable to reach their sources because of the communications blackout. It made basic tasks of information gathering and fact-checking impossible. Moreover, the report found that travel restrictions limited journalists from exploring the impact of the blackout in other areas of the region.

With fewer options, many were “forced to depend on the information circulated by the government”, the report said. For this reason, many of whom the researchers interviewed said they did not know the true scale of the arrests and detentions in the aftermath of the blockade.

For freelance journalists, reporting during the internet blackout was even more precarious as they were barred from using the media facilitation centre the government set up for journalists, the report found. It was the only centre where journalists could use the internet, send emails and file their reports. The reporters who could use the centre found it to be a “site for surveillance”, as they feared their online activity was monitored and their email passwords compromised.

Largely, the absence of the internet slows down journalists from doing their jobs who then have to scramble and find ways to “accommodate the inconveniences”, the report said.

“Journalists incur an opportunity cost when they are forced to spend significant time trying to file their stories and, combined with a surrounding chaos of a protest/conflict zone, some stories may be missed,” said the report.

Blackout At Protests & Courts

Internet services were suspended on various occasions during protests against the Citizenship Amendment Act, 2019, and the National Register for Citizens between 2019 and 2020, the report said. Such instances were reported from Delhi, Uttar Pradesh, Karnataka, Assam, Meghalaya, Arunachal Pradesh, Tripura, West Bengal, Madhya Pradesh and Rajasthan.

Orders to suspend the internet were not necessarily shared in advance, the report found. Though some activists the report quotes said that this effectively stopped citizens from “expressing their reality, which is tied to their protected right to exercise free speech and expression”, especially when the protests go against the state.

In such cases, Internet blockades impact the way activists go about their work to mobilise more people. Most of the time, they depend on social media to be able to gather more people for the cause. In the absence of the Internet, the report stated that a “great deal of human rights abuses recorded during protests were not brought to the attention of the public until days or weeks after the incident took place.”

The lack of internet also affected the way courts were able to perform their functions, the report found. It noted that lawyers were unable to download documents or print them. In court complexes, lawyers could not check what time their matters were listed or find out additional details like the case status, access case documents. Many litigants were unable to send lawyers their documents over WhatsApp either, the report added.

It made the following observation about the courts: “The judiciary has been reluctant to recognise a right to access the internet and that no order has been decided by the courts requiring the government to lift internet restrictions.”

How Journalists Cope

Internet shutdowns have not only adversely impacted local businesses and residents, but they also have a wide impact on the way human rights defenders, journalists and lawyers function. For journalists especially, the Internet is a key medium to file news reports, access data and contact sources.

The report said that the absence of the internet pushed media personnel to scramble and find innovative ways with their limited means to get their stories to reach the public.

When New Delhi shut down the Internet in Jammu and Kashmir for 552 days in 2019, one of the longest shutdowns recorded globally, most journalists in the region were unsure how they could do their jobs. At the time, the report stated, reporters relied on “pen drive journalism”.

This meant that reporters wrote their stories, took photographs and saved data on pen drives, which some of them would travel and deliver to offices in Delhi.

Months later, when broadband was restored in Jammu in November 2019, several travelled to a town known as Banihal in a train dubbed as the “Internet Express”. In Banihal, residents from the region and journalists would queue up outside cyber cafes to use Internet services for Rs 300 per hour, according to the findings of the report.

In other cases, journalists had to literally climb uphill to access the Internet.

In 2017, the internet was suspended for at least a 100 days while the agitation for Gorkhaland soared in Darjeeling, the northern most part of West Bengal. As the region borders Sikkim, journalists were able to get Reliance Jio signals on their phones after they climbed atop a hill in Darjeeling, according to the report.

“Rakesh’s [a journalist] routine during that time was to attend press conferences, write stories, and go to Jio Hill to catch a strong enough network signal to send out his stories,” said the report.

Such suspensions can also profoundly affect the way citizens engage with a government and express their dissent, the report said.

For instance, it noted that internet blockades were enforced during the protests against the CAA.

During that time, many took to Twitter to post updates of active protest sites, mobilise more protestors and share videos and photos depicting public participation or police attacks on protestors.

The shutdowns during protests also gave rise to a conversation about pushing back against the shutdowns, the report said. Twitter users shared articles on how to tweet during a shutdown and the communication apps to download which would work offline as well, it added.

Lack Of Accountability

The union government said it imposed a long shutdown in Jammu and Kashmir for reasons of “national security”, as stated in the parliamentary standing committee for communications and information technology report in December 2021.

The standing committee repeatedly questioned the efficacy of such shutdowns and asked the ministry of home affairs and the department of telecommunications under the ministry of communications for the relation between Internet suspensions and violence as civil unrest took place even before the Internet.

But both the ministries were unable to explain a correlation between the internet and communal riots, the standing committee noted. It urged the government to maintain a centralised database of such shutdowns with details of the duration and reason for ordering the shutdown.

The Centre for Human Rights’ report pointed out the numerous obstacles in the way of lawyers who wish to challenge Internet shutdowns and demand accountability from the government.

“The problem with short Internet shutdowns is that by the time the matter can be effectively heard and decided, the Internet has been restored and the case would likely be considered infructuous by courts,” the report stated.

Finally, the report asked—is there a “sensible” policy to shut down the Internet?

While the answer to this lies in how transparent the government is, the report noted that internet suspensions were “not worth the cost and collateral damage imposed on people”. There is no empirical evidence to support the argument that such shutdowns curb rumours and violence, it said.

(Vijayta Lalwani is an independent journalist covering politics, labour rights, polarisation and political violence.)