Kolkata: “I ran from his room, my head feeling dizzy and my heart pacing wild, as his words, ‘hug me and get back to work’, played on repeat. I rushed down the stairs, grabbed my bag from the chamber downstairs and headed out, refusing to look back till I was sufficiently far from the house…”

After graduating in law at the age of 22, A*, like most first-generation lawyers from traditional law colleges in Kolkata, who join chambers of senior dada’s (alumni who now have their own practice or strong contacts with big chambers), approached a senior from her college to assist.

On her first day in court, the senior, in turn, took A to another advocate he worked under, a regular face at the High Court at Calcutta. After a brief conversation, the advocate, in his fifties at the time, sitting inside a courtroom, surrounded by many juniors/interns, allegedly said, “… this one is really shy, huh? You can join, but in this profession, you need to free up.”

In an interview in the summer of 2023, three years after the incident in 2019, A recalled nodding awkwardly.

In a few moments, everyone prepared for a chamber photograph as it was the advocate’s birthday, and A was asked to join too. She hesitated, but he insisted that she stand beside him. There were giggles and comments from his juniors, one of whom allegedly said, “In three months, all the shyness will disappear.”

The advocate laughed too and posed by wrapping his hand around A’s shoulder, briefly rubbing his fingers against her arm. The photograph was taken, yet the hand remained there for a few more seconds.

Scared and confused, A told herself she was misunderstanding.

Three months later, A assisted him in a rape case along with two juniors. As directed, she read the victim’s complaint aloud. At times, discomforted by certain explicit details, she omitted words including ‘penis’, etc and moved on with the sentences.

“He asked me, 'Don't you have a boyfriend? Have you never seen?' I froze for a moment and said no. Some juniors smiled amongst themselves. Visibly angry, he said this was the reason girls like me should not enter litigation,” she said.

“I started crying, and he sent others out and then yelled at me saying I was incompetent, while frantically drawing images of a penis and a vagina on a paper…asked me to look at it and learn,” she said.“As I looked away and sobbed louder, he was quick to throw the page in the bin and asked me to leave”

After the incident, A stopped attending the chamber for a week. She said the other juniors messaged her saying that seniors get angry and one cannot be sensitive. She added that the advocate also messaged her, saying that, in criminal practice, inhibitions should be shed, and since he treats everyone the same, A should not feel uncomfortable. He allegedly insisted she meet him in his chamber at his house at 9 am the next day.

“I was extremely confused at that point, and would blame myself for feeling uncomfortable and crying in public,” she said. “That day’s events replayed in my head, and I shrank in embarrassment. Reading his text made me feel more guilty about myself, and I wanted to go back to work.”

A reached the advocate’s chamber. Within a few minutes, she said, he summoned her upstairs to his room. The floor was empty, so she waited in the sitting area.

She said, “He called me from somewhere inside, and I responded, but he kept saying he couldn’t hear me, so I followed his voice inside the room. In a few seconds, he appeared, wrapped in a towel, and drying his hair, saying, "Nowadays, you people are so sensitive that the senior has to cajole you. We have been yelled at louder but never shed a tear.”

A looked down quietly.

He allegedly continued while putting on a shirt, “I have never allowed any junior in my room, but I saw an honesty in you, very important for this practice, therefore, I am making an effort, being frank.

“‘Now give me a hug and let's get to work,’ were his words,” she said, as he allegedly walked towards her, still bare bodied. A’s heart sank for a few seconds, her head felt dizzy, but she finally gathered the courage to run away.

A few days later, she said, she received a message from his junior stating that she should not have gone upstairs, but now that she has seen the senior in that state, she should forget about it and return.

“At that point, I was scared, confused and mentally drained, but later, after replaying the events a thousand times in my head, I realised how he caught on to my weakness and was documenting a different version of the incident with his team each time. So, if I ever raised my voice, I’d not have their support but be blamed instead.”

A never returned.

A said that when this happened in 2019, she didn’t know of the existence of any internal complaints committee (ICC) within the high court, which may have been formed under the Sexual Harassment of Women at Workplaces (Prevention, Prohibition and Redressal) Act, 2013 (2013 Act), that mandated ICCs in every workplace.

ICCs were established under the 2013 Act, which arose from the Supreme Court’s 1997 Vishaka judgment that issued the Vishaka Guidelines to address workplace sexual harassment. The ICC consists of a woman Presiding Officer, at least two employee members, and one external expert from an NGO or similar body. It is meant to receive and investigate complaints, ensure fair inquiry and recommend appropriate action to promote a safe, gender-sensitive workplace.

The High Court at Calcutta too has such a committee, called ‘The Committee for Prevention of Sexual Harassment of Women at Office/Workplace’, that was formed in April 2010 by the then Chief Justice, pursuant to the aforesaid Vishaka guidelines. Currently, chaired by Justice Shampa Sarkar, the committee includes judges and registrars of the court, and an independent member from Legal Aid Services, West Bengal.

The population of female lawyers is minuscule in Indian litigation, with the ministry of law and justice’s department of legal affairs data showing that, in 2022, only 15% of advocates enrolled with state bar councils were women.

Travelling across West Bengal, I saw that women lawyers are concentrated mainly around the High Court and a few big district courts, such as 24 Parganas South and Calcutta; the number decreases drastically in the rest of the courts.

The Missing Internal Complaints Committee

A’s exit is not exceptional.

Neither is her lack of knowledge of a redressal committee in the court.

In 2023, I interviewed a woman practising at the Calcutta High Court for 10 years who said, “Even though I have not faced sexual harassment, but have seen many of my colleagues being in such situations, some of who had to leave litigation and pursue career in teaching, etc, seeing their experiences, I have been apprehensive about my safety too.”

On asking if she advised her colleagues who quit litigation to report to an ICC, she said, “Is there an ICC in our court? I don’t know.”

In fact, of the 70 women lawyers at the Calcutta High Court whom I interviewed from 2022 to 2024 (based on their experiences as women in Indian litigation), most believed there was no ICC. Though three women vaguely recalled having one, they were not sure whether it even included female lawyers within its ambit of ‘aggrieved women’.

On 31 January this year, the Calcutta High Court publicised a notification of its 15 year old ICC on its official website for the first time.

However, to truly understand the significance of this publication, it is important to document the decade-long institutional silence the high court maintained on the committee and the data available on it.

In 2022, I discovered the existence of this now-publicised ICC through the High Court registry. Although the committee was formed so long ago, it remained behind a veil, neither appearing in the court premises nor on its website.

In response to my Right to Information (RTI) queries, only three complaints were filed by May 2022: one was disposed of with an apology from the perpetrator, and two were ongoing.

Before 2025, even though the Annual Report of 2022-23 of the Court did briefly mention the ICC (with no further detail), responses received from RTI requests from 2021-2023 showed there was no documentation of an official notification or an internal policy/ charter, no workshops or training programs conducted, and, no data on a complaint box for a victim to file a complaint of sexual harassment.

While some of the court's senior officials, whom I met multiple times from 2021 to 2022, mentioned a “certain register book” they remembered or a meeting they had heard of long ago, little data was ultimately found. More importantly, until this time, there was a lack of clarity on who was included as ‘aggrieved women’ within this committee; officials informed me orally that it was perhaps for the women staff.

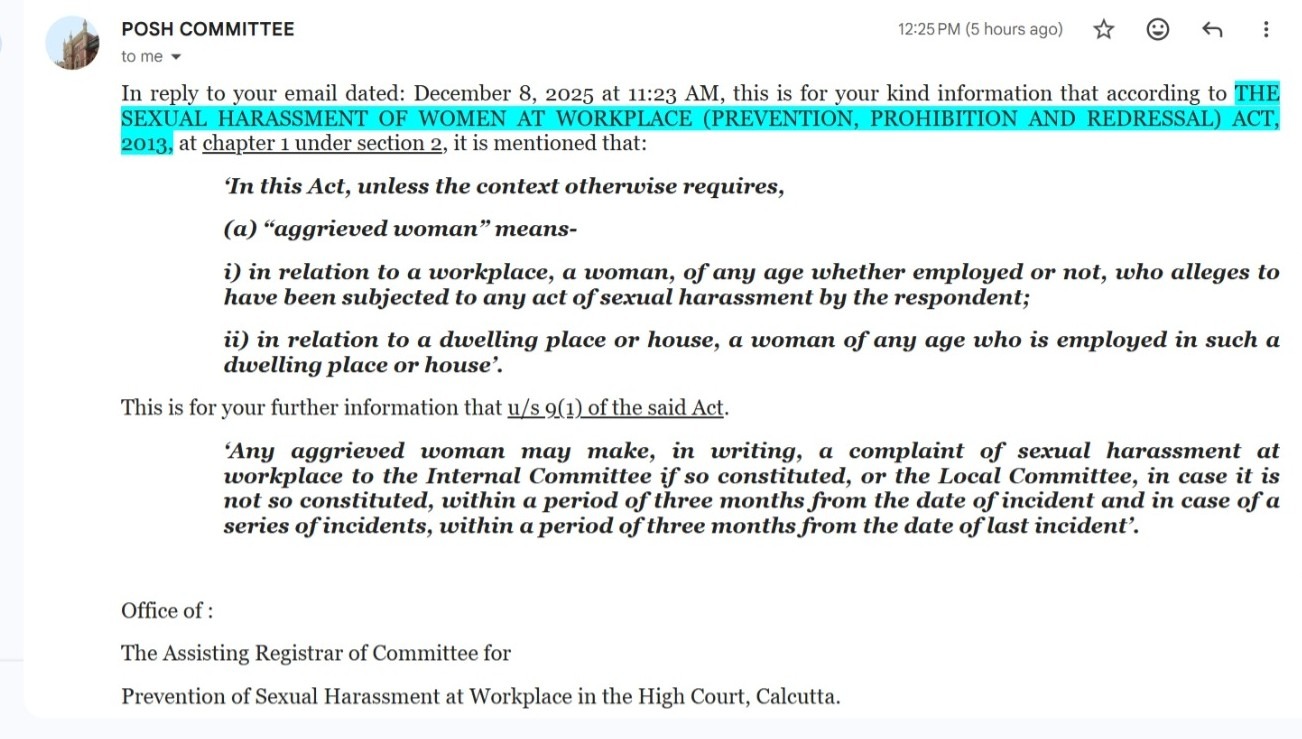

By January 2023, however, I had received a written response stating, “refer to the 2013 Act,” which states that it covers “a woman”, “whether employed or not”, during their course of work, thus technically covering lawyers, too.

Aiming to address these several lacunas and confusions, I filed a public interest litigation (PIL) in 2023 before the High Court, praying for a proper implementation of the ICC as per the 2013 Act, including its publicisation along with an internal policy/charter (among others), which a division bench dismissed as “premature”. I was directed to approach the court registry.

The registry, however, did not publicise the committee.

Finally, this year, a committee poster was seen on the wall in one of the corridors, listing a helpline number, an email ID to contact the committee, and the location of a complaint box. The ICC’s first ‘inaugural workshop’ on sensitisation of employees and members of the legal fraternity was held on 4th November 2024, while the second was held on 4 April 2025.

Even though this publicization is a statutory compliance with the 2013 Act and a minimal effort on the part of the institution, it remains a significant step given the 15-year delay.

The Supreme Court had taken note of the reality of sexual harassment of women within courts, particularly women lawyers, in 2013, in Binu Tamta vs State of Delhi High Court & Ors. It formed the Gender Sensitisation & Sexual Harassment of Women at the Supreme Court of India (Prevention, Prohibition and Redressal), Regulations, 2013 (GSICC), a grievance cell to redress complaints of sexual harassment within the precincts of the courts, and directed every high court and district court in the country to form the same.

Following this, at least 15 high courts formulated their own regulations, some excluding women already governed by the respective service rules from the ambit of ‘aggrieved women’ (thus including lawyers and others who are not employees, specifically). To date, each of these courts has the GSICC publicised on their websites.

The Calcutta High Court had not complied with this direction then. Now, it is unknown whether this was because the present ICC, formed in 2010, already included lawyers—no gazette notification or internal policy was available to show that.

However, as of now, the Chairperson, in the Annual Report of 2024-25, clarified that the committee ensures the safety of “all women within the precincts of the High Court”. In fact, an official response was sought from the committee this month as well, on whether the ICC includes female lawyers. It replied, stating the definition of aggrieved women in the 2013 Act, thus technically welcoming lawyers.

Institutional Silence In The District Courts

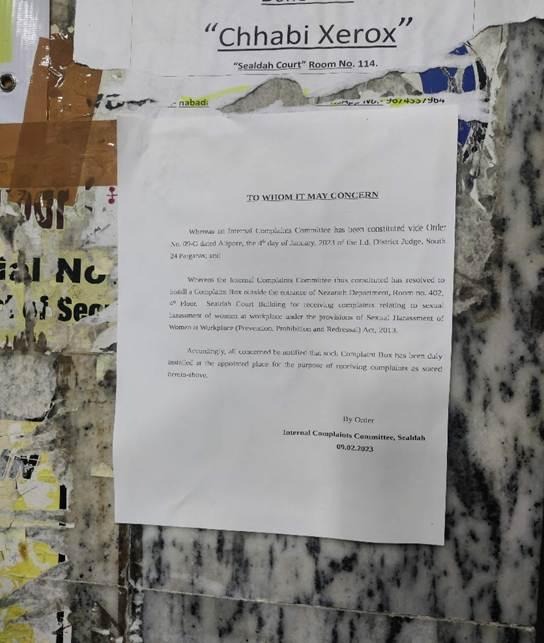

When I visited the Sealdah district court in the South 24 Parganas district in 2023, I saw a notice about the ICC attached to the lifts, and a complaint box was visible, even though the details of the adjudicatory committee were absent.

Through RTI responses (in July 2022), Jalpaiguri, Uttar Dinajpur, and Paschim Medinipur district courts said they had ICCs, two formed in 2018 and one in 2015, respectively. Yet, the 11 women in Jalpaiguri, 6 in Uttar Dinajpur and 15 in the Paschim Medinipur Bars that I spoke with did not know of their existence, nor were they able to direct me to any poster in the premises.

Also, Paschim Mednipur and Jalpaiguri did not have an external member in the adjudicatory body, while the former additionally had a lawyer and the 2 did not.

The remaining 20 courts to which I sent RTI queries were unresponsive (and no publication either found in the court premises or clarified by local women lawyers), even though the high court in January 2023 responded to me stating all district courts had complied with the 2013 Act.

Interestingly, whenever there is a question on the institution not complying effectively with the 2013 Act, the responses I received from the court registrars and male members of the Bar were two-fold: the burden of finding out about these committees was on the women, publicising would be met with false complaints, and male lawyers simply denied there was "bad behaviour" towards women.

In fact, both the responses were encapsulated together during the hearing of my PIL too where the then Chief Justice orally remarked whether I was being "sponsored" by someone or whether a "gun was being fired" from my shoulder (even though it is the same Chief Justice who before retiring, led the publication of the ICC and initiated conducting of inaugural workshops in 2024-25).

However, I was told that in cases of litigants harassing women lawyers, the Bar actively intervenes: FIRs get lodged and lawyers refuse to represent them. But as a woman from Siliguri court observed, “My complaint against a member of the Bar collects dust, while they protest against outsiders.”

‘Just Because I Said No’

When a lawyer from the Nadia District Court did not find an ICC, she complained to the local Bar against a male colleague who was allegedly regularly stalking and propositioning her to meet outside court alone.

“Who knows where my complaint is lying? Nothing ever happened,” she said

A woman lawyer in Paschim Bardhaman district court described how, after she left a senior’s chamber following lewd comments about her having an affair with him, and tried working independently instead of joining another senior, she was subjected to crude and unseemly comments by a group of lawyers, like, “you will only gain by sitting with us and not alone…”

“These comments were followed by them playing pornography in the Bar room, sitting beside me and engaging in sexually coloured conversations regularly,” she said. “Just because I said no, the male ego of the seniors was hurt; they would do anything to either make me conform or leave the Bar. I chose the latter.”

She built a makeshift chamber outside the Bar room, where the same group would throw garbage every day. Within a few years, she transformed it into a tile room too, but in her absence it would be dismantled and she would rebuild it.

A lawyer from a court in Paschim Medinipur recalled how 10 years ago, protesting in public against “unwanted physical touch” forced by a male lawyer had prevented her from sitting inside the association room from the next day and labelled a ‘meyechhele lawyer’ (derogatory term used for female lawyers) by the Bar.

She felt that women today, though more in number, are still compelled to tolerate bad behaviour by male counterparts, hoping silence would protect work opportunities.

“It’s a cycle,” she said. “If you stay silent and tolerate, words spread within a Bar like fire, and it is again you who gets slut shamed by the community, and if you break the silence, you heard my story. In both ways, the man at fault is never in the picture, so why keep quiet?

(Senjuti Chakrabarti is a criminal lawyer having practised in the High Court at Calcutta and Trial Courts in West Bengal. She is currently working at The Square Circle Clinic, NALSAR University of Law as a death penalty litigator)

Get exclusive access to new databases, expert analyses, weekly newsletters, book excerpts and new ideas on democracy, law and society in India. Subscribe to Article 14.