In a career spanning more than four decades, Harinder Baweja has borne witness to some of India's most turbulent moments—from Punjab’s insurgency to the long, bruising conflict in Kashmir. A veteran war correspondent and one of India’s most respected journalists, Baweja, 64, has won the Ramnath Goenka Award for excellence in journalism, the Prabha Dutt award, and the Haldighati award, among others.

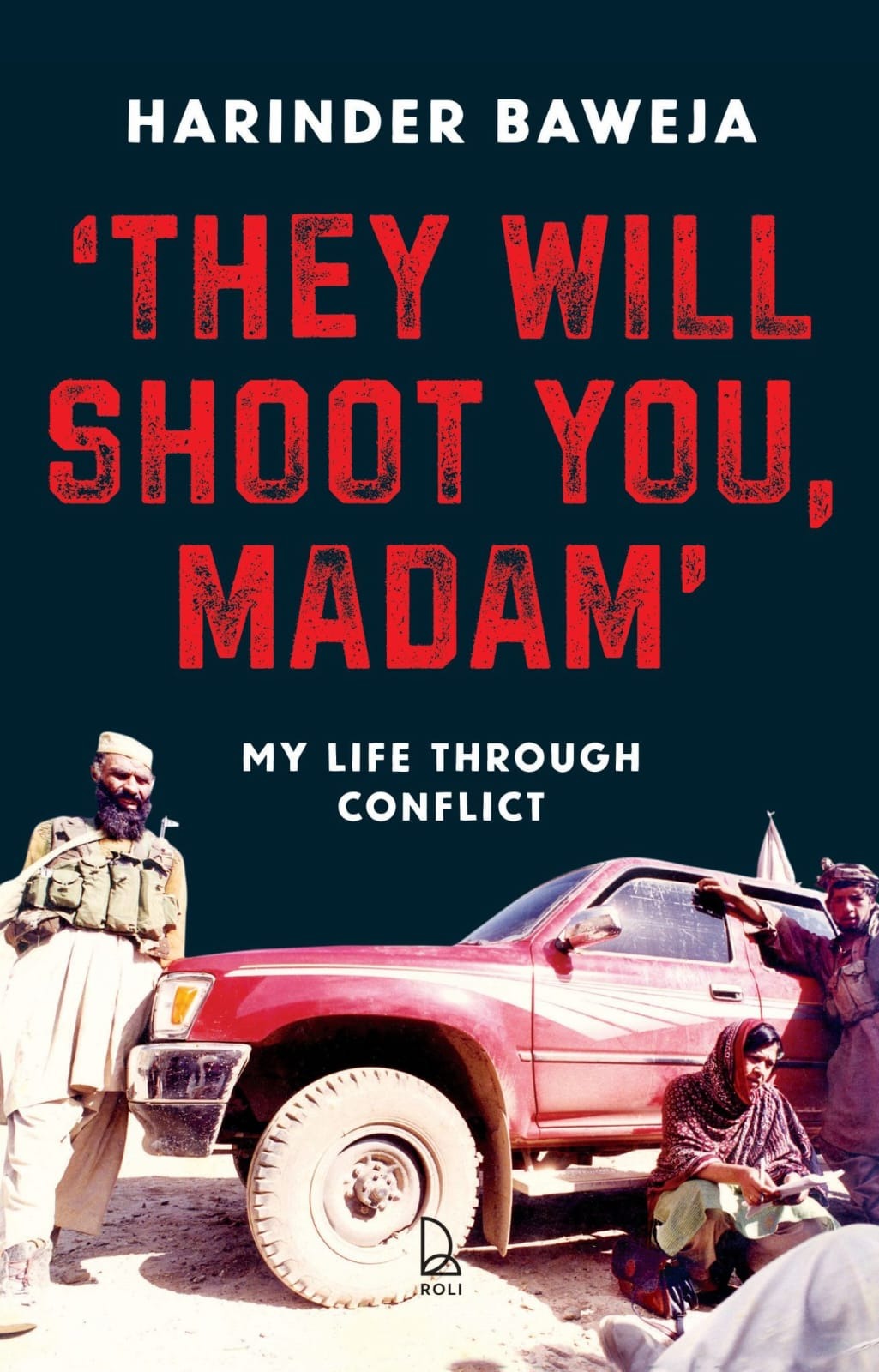

Her new memoir, They Will Shoot You, Madam, is both a deeply personal and political chronicle—an unflinching look at what it means to report from battlefields, the costs that came with her newsroom nickname, ‘Bullet Baweja’.

The book travels through the smoke and silences of India’s conflicts, from Operation Blue Star and the 1984 anti-Sikh riots to the Babri Masjid demolition and the ongoing alienation in Kashmir. It maps the steady erosion of the country’s secular fabric as she witnessed at multiple instances.

In this interview, through the lens of her own experiences, Baweja recounts how the journalist’s task of holding truth to power and the ethos of fearless journalism are fading in an era of eroding press freedoms; and she describes how the conflicts she covered punctuated the evolution of a country where the right to question, to dissent, even to pray, stands diminished.

You belong to a generation of journalists that truly “walked the talk.” How do you reflect on the contrast between that ethos of journalism and the work produced by reporters today, especially from conflict zones?

I’ve often been called fearless, but there was a time when journalism itself was fearless. I was very lucky to be out in the field 40 years ago when you could actually hold a mirror to the ground, follow what is a journalist's essential remit, to hold truth to power. We did not think twice. We did not second-guess. Operation Sindoor, on the other hand, actually taught us what journalism is not about. We were taking Karachi one day; we were taking Lahore one day. Every single channel says they offer sense, not sensationalism. But all we seem to get on mainstream television is sensationalism. I've been covering conflicts for four decades and I had a problem watching news channels during the course of Operation Sindoor, even though it was an important part of my beat and my core interest. So, journalism the way it's practised today, to be honest, I do not recognise it.

You write of the BJP’s claims after the Babri Masjid demolition that there were over 50 temples destroyed in Kashmir, and you set out as a journalist to fact-check the BJP. Can you recount that experience?

On the 6th of December, 1992 when we saw the domes of the Babri Masjid being torn down and the sky was billowing with smoke, and the riots started soon after, it was clear that the charioteer, L K Advani, had lost control of the mob. That's how conflicts begin.

I was reminded about Punjab that year, about how Indira Gandhi had let the genie out of the bottle when it came to Jarnail Singh Bhindranwale, and she had never been able to put it back. I knew what a deep wound was caused when she had to order the army into the Golden Temple, which is the most sacred of Sikh spaces. My family lived through the 1984 carnage. As I've written in the book, my father had to take off his turban one day and don a helmet to reach home alive.

Coming back to your question, Advani was sort of swinging between two emotions and arguments after he'd lost control of that mob. One, he said it was the saddest day of his life. And two, on the other hand, he started to justify the demolition by saying, “But what about the 40 temples in Kashmir?” The contention was almost that as temples had been damaged in Kashmir, it was okay that the Babri Masjid had been torn down. He was trying to draw that equivalence.

I was working with India Today magazine at the time. Aroon Purie, the editor-in-chief, called me to his office and said, “Get a list from the BJP. This is the only way to do this story. We have to demolish this myth if it is in fact a myth.”

I went to the BJP office but it was very difficult to even get a list. And when I got lists, I got different ones. The BJP office in Jammu had 81 temples on its list. The Delhi office had a separate list. Within the BJP in Delhi too there were separate lists. Anyway, I went armed with all these different lists to Kashmir, accompanied by a woman photographer who was going to Kashmir for the first time.

This was one of my toughest assignments because when we reached various temples around Srinagar, we were suspects as far as the local population was concerned. By then, the Kashmiri Pandit community had migrated. (That's another story I've covered. And it's important to point out the pain of them having lost their home, and the thought that they would never make it back. They simply haven't been able to come back to a place called home.)

The valley obviously didn't have too many Kashmiri Pandits, but the temples were there, as were pujaris. As my chapter recounts, the Kashmiri Muslims were very agitated. They thought I was there to defame them, to say that there actually had been some damage to the temples. It was a risky assignment, and Shipra and I had at one point bullets flying over our heads.

But my findings were completely the opposite of what Advani was trying to showcase. At the time, India Today did fearless journalism. I remember the article being reproduced in so many other publications.

Our finding was that temples had been demolished in Jammu & Kashmir after the demolition of the Babri Masjid, not before. In 1986-87, there had been riots in Kashmir, and mosques and temples were both damaged but they had been rebuilt. The ones that had been rebuilt were the ones on the BJP’s list.

1992 was quite a turning point in contemporary Indian political history. The communal divide was born with the demolition of the Babri Masjid, and has deepened and now become a full-scale fault line.

These days, we have all kinds of jihad. If it's not love jihad, it's food jihad. If it's not food jihad, it's trade jihad. During Rakhi, there was a rakhi being sold with a moon and a star that people on social media called rakhi jihad. We're constantly looking out for jihads.

Was there ever a moment, whether this one or any other, when you questioned whether the story is worth the personal risk? And do you ever weigh the moral calculus of danger versus duty as a journalist?

I did face that moment, and it changed the way I approached my own reporting of conflict, and it happened early in my career, in Punjab.

I was covering Operation Black Thunder, the second operation after Operation Blue Star. For the second time, the Golden Temple had been converted into a fortress and was armed to its teeth.

One evening, I got an interview with Jagir Singh, a dreaded terrorist, also heading the Panthic Committee, which is an important body that controls the Sikh faith. The Panthic Committee was also where Bhindranwale himself had come from.

One evening, sitting face-to-face with Jagir Singh, I asked about the dip in violence in Punjab, where I was posted then. He fell silent for what seemed to me like a very long time, a disturbing silence when he seemed lost, deep in thought. Finally, he looked at me, and he said, "You know, you don't have the same level of hunger every day. You don't need to eat two chapatis for lunch and two chapatis for dinner. On some days you feel more hungry, and some days you feel less hungry.”

That was a freeze (sic) moment for me. Soon after I did that interview, I went to meet CPI leader Satyapal Singh Dang, one of the few who was calling out terrorism at the time. His landline phone rang, and I saw his face change colour. He put the phone down, and told me that there had been a terrorist strike. Nine to 10 people had been killed. I don't know why, but I felt responsible. I felt maybe my question had been the wrong one to ask.

I understood that day that the origin of conflict does not lie in numbers. It doesn't lie in so many terrorists killed or so many arrested, or so many numbers of weapons recovered. It actually lies in the sociology and psychology of violence. And, that's what I focused on afterward. I've centred my reporting on conflict through that compass, and of course, through the lives of the non-combatants because they are the ones who face the consequences of conflict the most.

At multiple points in the book, you write of events suggesting that India's secular dream was dying, in 1984, then in 1992-93, and then again in later years. Did you ever feel that you were almost documenting a pattern?

The word secular has become like a gaali (a perjorative) today. It's become a bad word. It's flung at you as if it's wrong to be secular.

Having grown up in Indian Air Force cantonments, secularism was for me a lived reality, not a label or a title. Growing up, and even as a journalist, I’ve seen temples, mosques, churches, and gurdwaras built side by side. That's how the defence forces functioned. Today, even the defence forces have forgotten that ethos of secularism.

I've seen the fault lines deepen in Kashmir, for example, a place I have visited once or twice a month since 1989. I remember the ground beneath Kashmir's feet shifting after the brutal lynching of Mohammad Akhlaq in Dadri, on the outskirts of Delhi, in 2015. He was the first of the several lynching victims who followed.

When I was travelling from one village to another to find out why young, educated boys were choosing to leave the comfort of their classrooms and pick up the gun, like Burhan Wani did and several others did, including men in uniform, I was surprised to find that Akhlaq had become a household name in Kashmir. One of the families I visited was that of somebody who had donned the uniform and then taken it off before disappearing into the jungles of South Kashmir with their service weapon.

What happened in Dadri, and later across several states, actually deepened the conflict in Kashmir.

I've been watching conflict zones for over four decades now. I've seen how politics can make conflict murkier, and it’s sad but the adage that governs political parties is that the more you divide, the longer you rule. Unfortunately, even though they try to redefine patriotism by giving it a very jingoistic, muscular form of nationalism, they unfortunately end up tearing the social fabric of India.

Whether in Punjab in the Eighties or Kashmir and beyond, did you ever have the feeling that the Indian State's learning curve on how to deal with conflict was moving upwards?

When it comes to state policy, I don't see a coherent, cogent state response. In so many conflict zones I’ve witnessed from up close, I've seen how prime ministers and chief ministers have approached the very critical issue of internal security, defence, national interest.

In Punjab, we had rivalries added to the murkiness of what was playing out on the ground. The chief minister was not getting along with the home minister, and thus two important stakeholders were at each other's throats.

In Kashmir, I've seen prime ministers try to make an effort, but I don't see any continuum, and I think that's an important part of the problem. So in Kashmir you have a litany of broken promises. P V Narasimha Rao said, “Anything short of azadi.” Deve Gowda said much the same thing, you know, something about the sky being the limit. Atal Behari Vajpayee, who actually endeared himself to the Kashmiris, said, “Kashmiriat jamhooriat insaaniat (Kashmir’s syncretic identity, democracy, humanity).”

Let's talk about the current prime minister. Prime Minister Modi at one stage, I think at an all-party meeting soon after COVID and soon after Article 370 had been killed, talked about the need to reduce the distance between Delhi and Srinagar. So, we've heard articulations of state policy, but I have not seen too much of that being applied on the ground.

Pahalgam comes as a crucial reminder of the fact that Kashmir is still waiting for a political outreach. I've seen personalities play a role in how they approach conflict resolution, and I would say ideology is now playing a role in how the government is approaching conflict resolution. Because frankly, what was the killing of Article 370 all about? It was about fulfilling a promise that had been on the RSS's agenda for a very long time.

I don't think that kind of politics will allow too much room for actual peace. Anybody who tries to walk that road to peace has a very long walk ahead. And I don't see anybody on that road.

Conflict tends to present itself much more differently to women as compared to men. How was it different being a rare woman journalist in the field in conflict zones?

I've never sought concessions as a woman journalist because all I wanted is to chronicle and tell stories. As a journalist, I've never allowed gender to come in the way, but unfortunately, the players in the field do not see it the same way.

I had to go through a very petty and personal attack when I was posted in Punjab in the 1980s, when I had policemen show up at my door early in the morning. When I saw men in uniform at my door, as a journalist, my first thoughts were, “Is it to do with something that I've written? Or is it to do with the fact that I've interviewed militants in the Golden Temple?”

I wasn't prepared for what was coming. When I asked for a copy of the complaint, one of them said they cannot give me a copy. “But, you know, there's too much noise in your flat at night, and there's senior IAS and IPS officers visiting you,” one of them told me.

My knees were knocking. I was jelly. I was still in my 20s. It was my first battlefield as a reporter. I was taking baby steps into a conflict zone. I was very rattled, but managed to put up a brave front, and told them if they can't give me a copy of the complaint, then they could leave. I shut the door on their faces.

I later went to meet the then director general of police, Julio Ribeiro, who said something to me that was my first important lesson. He said, “Even if officers are visiting you, it’s none of the police's business.”

I had a sudden peace descend over me when I heard him say that. And I've never looked back, I was just unhindered. That freedom came very early in life and taught me that I should just pursue what I'm doing as a journalist without bothering about personal attacks.

Then there was the Yasin Malik chapter. Yasin Malik, the separatist leader who was about to announce that he had put down the gun, had just been released from jail. He was extremely loved by the people of Kashmir, the Valley in particular, and important enough for the Intelligence Bureau to strike a deal with.

Upon his release from jail, he flew from Delhi to Srinagar. I was asked to come to interview him late in the night, and I didn’t suspect the reasons—I was told there were too many visitors.

It was very, very risky to be out on the streets of Kashmir after sunset. Every conflict zone comes with its own rules, and you have to learn them very quickly.

By then, he was accused of kidnapping Rubaiya Sayeed, the daughter of the serving home minister. He was also accused of killing four Indian armed forces’ officers. In Srinagar, he announced, “I’m now a disciple of Mahatma Gandhi.”

I went to the hospital to interview him. He was lying in a hospital bed, and he made a pass at me. It is a memory that is very difficult to shake off. I decided to put it in the book because, one, maybe I needed the cathartic comfort of words. And two, more importantly, I don't see why women should whitewash what happens to them.

Going back to the Kashmir Valley, which remains a militarised democracy. Do you feel that there can ever be a balance between security imperatives that come with the kind of conflict Kashmir has experienced and democratic freedoms that the Constitution promises?

As a regular observer of Kashmir—honestly, from the bottom of my heart, I call it my second home—and because I've spent so much time there just trying to study the various ebbs and flows, many chapters in my book relate to Kashmir.

I have seen Kashmir swing between hope and hopelessness since I started covering it, which was in December 1989. The lesson I've learnt is that in Kashmir, the pendulum swings without notice. We saw that happening in Pahalgam when the government was trying to build a narrative of a Naya Kashmir.

One point that governments perhaps understand but ignore is that the military, the security matrix that you referred to, also called the counter insurgency grid, can only contain the level of violence and bring it to a point when you then need to make a political outreach. And interestingly, the authors of the first surgical strike, Lieutenant General D S Hooda, who was commanding the Northern Command after the first surgical strike in Uri, and Lieutenant General Satish Dua, who was heading the 15th Corps headquarter in Srinagar, both felt there is a need to not treat Jammu and Kashmir like a piece of real estate, that we need to pay attention to the people who live there.

Not in my wildest dreams did I ever think that I would see the people of Kashmir take out a procession holding the national flag, and they did just that after Pahalgam. They were so upset that the blood of tourists had singed their soil, it was a very spontaneous outpouring, a condemnation of the attack. Local people opened their hotels, their mosques and their; locals drove panicked tourists to the airport.

Then we also saw two very sad things. One, Himanshi Narwal, the widow who'd been married less than a week before the attack when she was pictured sitting next to the lifeless body of her husband, had to call out hate. She was the one who said, “Do not demonise the Kashmiris and the Muslims. They are the ones who saved us. They are the ones who helped us.”

That was a perfect window of opportunity, but what was the response? The response was focused through Operation Sindoor.

Of course, the government is free to decide how to respond to the attack in Pahalgam, but what about the window of opportunity on the ground in Kashmir itself? What was the response there? Houses were strapped with explosives and shot to pieces.

I did an interview with Mirwaiz Umar Farooq, a very important stakeholder in Jammu and Kashmir, who leads prayers at the Jama Masjid on Fridays if he's allowed to. He said to me in the interview, “Why is it that my effort for peace is being seen as an anti-national activity?” He said something else that broke my heart. He said, “Why is New Delhi afraid of our prayers?”

For me, that's a very deep question, one that deserves an answer. Why can't we offer Namaz?

So there is a very dark cloud hovering over Kashmir, and the effort should be to try and win the people, instead of trying to focus on the territory.

It has been six years since Article 370 was hollowed out. It had been diluted over the years, but it still gave some amount of dignity to local Kashmiris. I think they would respond to a softer approach. Kashmir is crying out for a political outreach, which I don't see to be in the making as of today, at least.

Today, even Ladakh is upset with New Delhi. Sure. The same Ladakh celebrated their being made into a separate union territory, and now they're demanding statehood. If the BJP is waiting for saffron to reach the polling booths, then I'm afraid it's going to be a very long wait.

Tell us about the incident from where the title of the book emerged, They Will Shoot You, Madam.

The title of the book could apply to a lot of chapters because covering conflict is risky, and you're always in zones where guns are pointed from different directions. But in this specific instance, I was in Anantnag, where we were trying to go into one of the temples listed as damaged by the BJP.

We made our way in, on all fours after bullets started flying over our head, and the pujari came to meet me. He was trembling with fear because he'd also heard the sound of bullets—several rounds had been fired. He was very shaken. He told me, “Don't quote me, but I'll talk to you."

Then he leaned forward and demanded to have my notebook. I really had no choice but to give it to him. He tore out the page on which I had written ‘Raghunath Mandir’, where this exchange occurred. He tore those notes into little shreds, etching in my mind a deep memory I'll never forget.

He thought that when I left, people outside the temple would want to know what he had said. He did not want to leave any trace of his conversation with me. The BSF, which was guarding the temple, was asking us to be prepared. They said, "Madam, goli toh chalegi. (Weapons will be fired.) They will shoot you."

As it was my colleague Shipra Das’s first visit to Kashmir, I felt responsible for her life. I also knew I couldn’t make the temple my home, so I had to leave. I also had a very simple rule in conflict zones—the art of neutrality. Everybody tries to co-opt you to their side, whether it’s a militant, a separatist, a politician, or any of the players. So I decided that I needed to get out of the temple.

I held Shipra by the hand and we came out of the temple. I was waiting for a bullet to hit my back. The same street that had been bustling when we entered, it now resembled a street under curfew.

I was worried about my local Kashmiri driver who I couldn’t see. As I took tentative steps towards where my car was parked, somebody signalled from one of the windows above the shops. Those last few steps until we reached the car and left were terrifying.

That’s where the title came from, the moment I was told, “They will shoot you, madam.”

(Kavitha Iyer is a senior editor with Article 14 and the author of ‘Landscapes of Loss’, a book on India’s farm crisis.)

Get exclusive access to new databases, expert analyses, weekly newsletters, book excerpts and new ideas on democracy, law and society in India. Subscribe to Article 14.