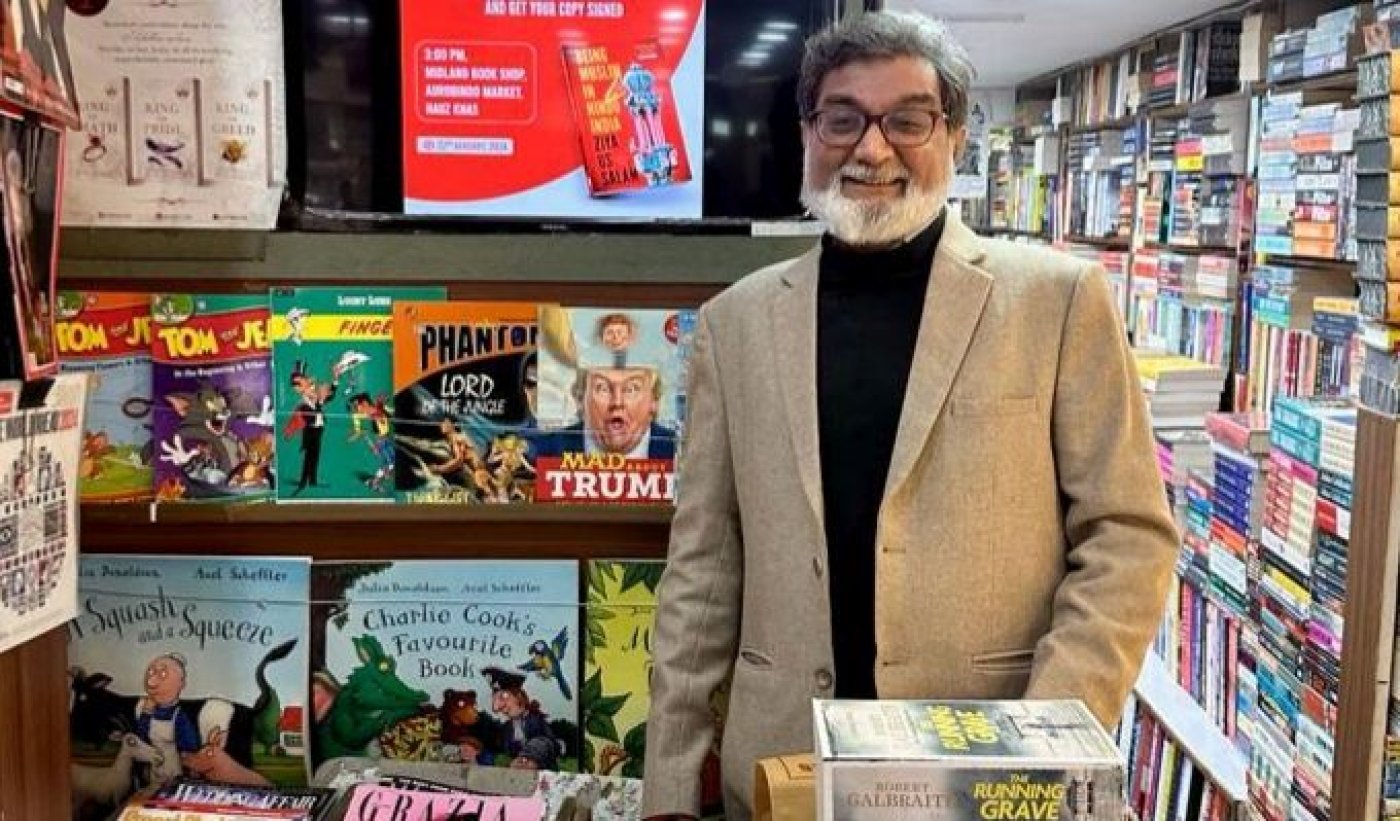

New Delhi: Among the six books Ziya Us Salam, 53, has written on the subject of Islam and lives of Indian Muslims, Being Muslim in Hindu India is probably the grimmest.

There are specks of optimism in his narrative, which discusses genocidal calls against Muslims given from public fora, the witch hunt of the Tablighi Jamaat during a global pandemic and the passion of Shaheen Bagh protests, but these are drowned by the reality of India’s treatment of its largest minority, which the book attempts to document.

However, the focal point of Salam’s narrative is the truth of being Muslim in today’s India and the community’s battle against prejudice and persecution, without any sense of bitterness against the nation.

In his book, he captures the transformation of India in a country where the survival of Muslims hinges mainly on one thing—appeasing the whims of the majority and accepting their status as second-class citizens.

In a passage, as an advice to the Muslim community facing ‘othering’ and persecution, Salam, a noted social commentator, writes: “For the Muslim community, life is all about a silent, peaceful jihad within, striving to make tomorrow better than today, everyone doing his bit to make sure the community focuses on the larger challenges of peace, and capitalises on the opportunities that it throws up.”

At other places, he turns the focus on those who, directly or covertly, support the blatant Islamophobia, among them, sections of national media. “Today, vast multitudes swear by the Hindutva hegemony. In this relentless, even violent bid for supremacy, there is no space for peaceful dialogue, for appreciation of differences,” writes Salam. “The Hindutva practitioner, in his mind, is sorting out the equations of the past.”

In a conversation with Article 14, Salam talked about his own relationship with his country. “Whenever I came home from a foreign country and got down from the flight, the first thing I’d do was to touch the land with my fingers, smell the soil and then exit,” he said. “Hindutva politics cannot take that away from me.”

Salam has worked with The Hindu for over two decades. Hailing from a family of Islamic scholars from Rampur, he lists Oscar Wilde, Arundhati Roy and Amitav Ghosh among his literary influences.

Salam talked to us about his book, his writing processes, the nuances of the Muslim identity under Hindutva, the changing face of nationalism and the upcoming general elections. Edited excerpts from the interview:

What was your intention behind writing Being Muslim in Hindu India? Were you concerned when you picked this title for your book?

The idea behind doing this book was two fold. At one level was the desire to bring attention to the constant othering of Muslims and repeated attacks on the idea of India. India is my motherland and I realise even the mother doesn't suckle her baby till it cries. This book then is an attempt to raise a voice.

At the second level, I wrote this book as a responsibility to posterity. Years later when history will be written of these dark times, the youngsters shouldn’t think we were too timid to speak up. For all the wrongs inflicted today, they must understand we did not succumb to fascist forces and did our bit.

You were born in a family of Islamic scholars in Rampur. Except for two, all your books have been on politics, Islam and the condition of Muslims in India. How much of your literary work comes from your decades in journalism and how much does it come from your formative years and your family?

I guess a man is a mixture of multiple influences. We inherit values from our parents, then we add lessons from our life experiences. My books have largely been an attempt at drawing attention to the wrongs being committed within the Muslim community and outside.

I am considered an outsider everywhere. Within the Muslim community, often there is a criticism against my writings revealing wrongs within the community. In the larger society, when I do a book like Being Muslim in Hindu India, there is no shortage of trolling and advice to go to Pakistan.

By the way, I have done a couple of cinema books too. They draw from my experience of being the film critic of The Hindu for close to nine years.

The first part of your book talks about the marginalisation of Muslims from politics. As of now, not even one of the cabinet ministers are Muslims. What are the steps Muslims can take to influence politics in such a time?

Honestly, there is little the community can do to change the discourse, except exercising its right to adult franchise and rallying like-minded people from all communities. The community is paying a heavy price for believing in tokenism of the so-called secular parties. The realisation has dawned that Muslims are the new orphans of India. Nobody wants to use the word ‘Muslim’ from a public platform.

You talk about being Indian and being Muslim many times in the book. What do you think are the reasons behind the majority opinion that being a Muslim and being an Indian are at loggerheads with each other?

Being Muslim and Indian are not diametrically opposite terms. Contrary to common perception, India is the land of our prophets. The first mosque here was built even before the instruction came for change of direction for offering namaaz (from Jerusalem to Mecca). During the Prophet's time, two mosques had been built here.

Islam teaches you to love your land and respect its laws. There is no contradiction between being a good Muslim and a good Indian. Those who think otherwise are willing consumers of fake stories being spread with the aim of othering Muslim. Muslims were here much before Savarkar and Golwalkar and their theories of pitrabhu (fatherland) and punyabhu (holy land).

Please take us through your writing process in writing this and other of your books. Is it consistent or dynamic, or depending on the subject matter of the book?

I am generally a slow starter. When I begin working on a book, I write little for the first few days, maybe just 500-700 words a day for a week or two. Then like a rickety car, I pick up momentum gradually. I don’t do many drafts before sending the book to publishers. Once the manuscript is submitted, I leave it to the editors, and avoid much debate unless essential.

In your book, you say Shaheen Bagh protest was “too much to take for the pro-Hindutva male, used to imagining the Muslim woman as a meek, helpless being, living under the fear of marital violence, used as a child-rearing machine, and dumped with the pronouncement of triple talaq”. Why do you think such simple, monolithic ideas about Muslims still continue to gain acceptability, even among even educated elites?

There are a couple of reasons. Our media, particularly the Hindi media, has spread this canard for years about Muslim women being the most exploited and vulnerable. And many have happily accepted that piece of media bigotry as the truth. While we saw a lot of attention on the issue of instant triple talaq, how come we do not hear much about child marriages in the majority community or why should in today’s age, a grown up, well-educated and earning woman be given away in marriage as kanyadaan.

Shaheen Bagh shook the ideological foundation of Islamophobia. It started as a protest but soon became a pilgrimage spot for all believers in the idea of India. It is our Liberation Square.

Recently Randeep Hooda was in news for a biopic of Savarkar. One section of your book deals with misrepresentation of mediaeval history. How much do you think dishonest fictionalisation of real events in pop culture is responsible for the post-truth society we currently live in?

Hindi cinema is guilty of deliberate fictionalisation of history. As cinema has a vast reach and multitudes of audiences are not aware of historical facts, this distortion of history is consumed as a fact. I hold the filmmakers largely responsible for spreading hatred in the society. Films like Padmavat, Tanha ji and the more recent Swantantrya Veer Savarkar are examples of bigotry masquerading as artistic freedom. Of course, it suits the ruling dispensation as the bedrock of its politics is made up of hatred and social divisions. Anybody who accentuates social tension is an enabler of fascism in today's times.

How have your ideas of patriotism transformed since the nation turned to Hindutva?

India is my country. I was born here. My ancestors opted for a pluralist democracy of India instead of theocracy in Pakistan. An Indian’s responsibility is greater today than at any time since 1947. We have to protect our India, our Constitution and make sure those who stood with the British during our freedom struggle are not able to ruin our nation.

Much before the Modi regime came to power, I had my own way of expressing love for the land. Whenever I came home from a foreign country and got down from the flight, the first thing I’d do was to touch the land with my fingers, smell the soil and then exit. Hindutva politics cannot take that away from me.

In your book, you talk about how Sudarshan News ran a programme against Indian Muslims qualifying UPSC, calling it a conspiracy. Why do you think the right wing is afraid of educated Muslims?

The right wing is afraid of all educated Indians. For them educated Muslim is an anathema. Their politics thrives on ignorance, hate and violence. They are intrinsically opposed to knowledge. And an educated Muslim, man or woman, threatens to strip them of their fig leaf.

Why do you think Muslims rally behind so-called secular parties when most of their secularism seems to be for political benefit?

It is a Partition legacy. After 1947, Indian Muslims had to choose between the Jan Sangh and the Congress. They opted for the latter as the Jan Sangh blamed them for partition of the country and believed there was no space for Muslims here. The Congress and the other so-called secular parties at least offered them safety and security. In return, the parties took the Muslim community for granted. For optics they indulged in tokenism, a Muslim Governor here, an iftar party there. But there was no attention paid to the socio-economic uplift of the poor within the community. That is why the Sachar Committee found Muslims at the bottom of almost all socio-economic parameters.

The community still rallies behind them because it cannot form its own political party. We saw what happened in the UP Vidhan Sabha elections in 2022. The farmers protested against the farm laws and the BJP but ended up voting for the very party they were opposing tooth and nail for a year. Such is the poison of communalism in our country today.

In one chapter of your book, you talk about genocide calls against Muslims given from Dharam Sansad in 2021. No concrete action was taken against anyone. What if that moral conscience that you are trying to rouse is dead?

Today, the crime doesn't seem to matter. The religious identity of the perpetrator and the victim is considered more important. It's like the old formula of ‘Show me the man, I will show you the rule’. Sad but it shakes ones faith to see those who gave open calls for genocide roam free. It is an indictment of our system. It’s not about Muslims anymore. It is about the rule of law.

What do you feel is the sentiment among young Muslim journalists towards the fourth pillar of democracy?

Most of the young journalists who started their career with me are well settled. Today’s youngsters have retained their spark and are pushing the frontiers of possibilities. When I see them making a mark in the cut throat world of journalism, I silently admire them. They are clearly keen to make the media more honest and responsible.

How crucial do you think the upcoming general election will determine how difficult or easy it will be to be a Muslim in India?

The upcoming elections are crucial not just for Muslims but for India's identity as a pluralist democracy. The world is watching. Our international honour is at stake. Will we survive multiple assaults at our institutions and have a free and fair election? The fear is mounting each passing day. More so when we see the bank account of the leading Opposition being frozen, the leaders of Opposition parties thrown into jail and even Chief Ministers not being spared.

Yes, Muslims have a lot at stake after systematic attempts at invisibilization of the community. Forget jobs and education, the largest minority community is in desperate need of peace and security. But one could say the same about a large segment of India's population.

(Zeyad Masroor Khan is a freelance journalist and author of City on Fire: A Boyhood in Aligarh.)

Get exclusive access to new databases, expert analyses, weekly newsletters, book excerpts and new ideas on democracy, law and society in India. Subscribe to Article 14.