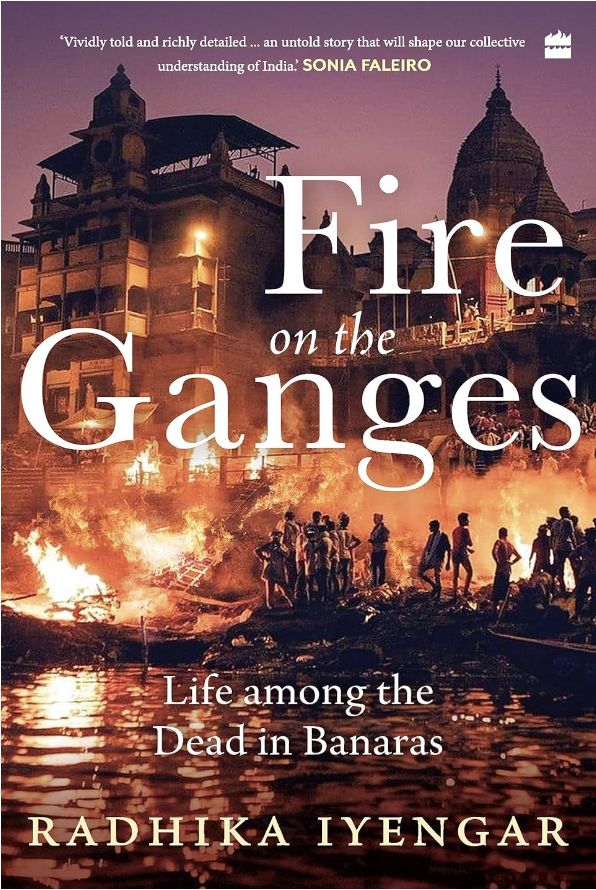

New Delhi: Varanasi, Banaras, Kashi, call it what you will, is considered the holiest city of the Hindus. Teeming with temples, pilgrims milling on the ghats along the Ganges, the air heavy with smoke and ashes, it is also one of the most photogenic cities for visitors from across the world. But under its mystique and spectacle lives a community, which, by the ancient laws of caste, has been tasked to emancipate the dead from moksha, the cycle of death and rebirth.

Radhika Iyengar’s debut book, Fire On the Ganges, focuses on the lives of the Doms of Varanasi, who, through generations, have been cremating the dead on Manikarnika and Harishchandra ghats. Without their fire, the dead can’t attain moksha, and yet, the living shrink away from their touch. The Doms are pushed outside the city, forced to live in an unsanitary ghetto, deprived of government welfare benefits and not given a chance to liberate themselves from the oppressive cycle of the caste system, which, by the accident of birth, condemns them to stay untouchables.

With eight years of field work, two to three annual visits to Varanasi, countless interviews done in person, on phone and via video calls, Iyengar captures the realities of the Doms by closely following the lives of five or six characters. The basti, where she focused her reporting on, had around 25 families living there. According to the 2011 Census, there are 110,353 Doms living in Uttar Pradesh.

A work of careful documentation, Iyengar’s book is also an investigation into the injustices that Dom women like Dolly Chaudhary live with. Yet, glimmers of hope shine through the cracks of unrelenting gloom. Lakshaya, a Dom boy, falls in love with Komal, a Brahmin girl, and against all odds, they manage to get married and have a life together.

We spoke to Iyengar about her reportage to understand the reality of the lives of the Doms of Varanasi, a city that is also the constituency of India’s Prime Minister Narendra Modi. Edited excerpts from the interview:

What drew you to the lives of the Doms of Varanasi?

When I was pursuing my masters in journalism at Columbia University in New York, I was researching for a thesis subject. I read an article about the Dom community and was intrigued. I wanted to learn more about the community. However, when I accessed articles and academic literature on it, I realised that there wasn’t sufficient information available on the community. Whatever was available focused solely on their work at the cremation ground.

I wanted to know more and learn more about them. Where were narratives that detailed other aspects of their lives? For instance, I wanted to understand how working at the cremation ground, handling the dead and earning a pitiable income, impacted the Dom men psychologically. I wanted to understand why the women from the community were not seen in public spaces. What were their aspirations? I wanted to know whether the Dom children were enrolled in schools. If they were, were they attending classes or expected to work at the cremation ground instead to contribute towards the household income? Many questions lingered in my mind. So, I decided to pursue it further.

As someone from a privileged caste and class, how did you build rapport and trust with your subjects?

I would like to respond to this question by citing a personal experience. The first few times I visited Chand Ghat (name changed), which is a Dom basti in Banaras, one of the community members offered me tea. We were all sitting on the ground and talking. The conversation was stiff and to the point.

When the tea arrived, we drank and chatted some more. I noticed then that the mood of the space had transformed. Those around me appeared more at ease. The stiffness disappeared. Our conversations became more interactive and engaging.

It was much later, after a few years had passed, that I realised that, of course, offering tea was a gesture of hospitality by the Doms, but it also carried a profound meaning. It was a way for them to gauge whether a person such as I, who was quite visibly from a privileged caste and class, was going to sit with them and drink tea as equals. It was this simple act of having chai together that day that broke an invisible barrier between us.

What were the initial years of reporting like? Did your gender affect your work within the ecosystem of Manikarnika Ghat?

Initially, when I began my field visits to Manikarnika Ghat, the Dom men weren’t very welcoming. I was an outsider, and they weren’t comfortable opening their world to me. More importantly, they were not used to a woman approaching them. So, I wasn’t taken seriously. I decided to then stand at a distance and patiently observe the men work and interact with each other. That enriched my reporting. However, I feel that my persistent return to Manikarnika Ghat and sustained efforts in trying to learn about their lives, eventually changed their opinion of me. They slowly began giving me some time of day for the brief periods when they weren’t too busy.

When it came to speaking to the Dom women, it was relatively easier. I was able to sit with them in the privacy of their homes (and not necessarily in the company of their husbands), which perhaps a male reporter would not be able to do. However, it did take them time to reach a point where they could be themselves or feel secure enough to have honest conversations with me. I was, of course, respectful of their time and ensured that I did not intrude on their space. Over the years, as we became better acquainted, our conversations became more intimate and more detailed. There were moments when they voluntarily shared certain experiences which they felt might help me.

You focus on the lives of a handful of extraordinary individuals. Tell us about a couple of them.

When I began writing the book, I was certain that I wanted to focus on the lives of a few individuals who were navigating a deeply caste-ridden, gender-biased landscape and taking life-altering decisions to live quite differently from the one imposed on them by society. So, while the book delves into the crematory work at Manikarnika Ghat to provide a broader context, it simultaneously narrows its lens on the lives of five or six individuals.

One of the protagonists is Dolly, a young widow and mother of five children, who opens a small kirana store right at the threshold of her one-room, ground-floor home in Chand Ghat. In the Dom community in Banaras, women are moored to household responsibilities and are not expected to earn a living. They are not allowed to have any financial autonomy. So when Dolly opens a store after selling all her jewellery, to support her children, it creates deep resentment within the community. The book follows her life, focusing on how she transforms from a naive woman who trusts everyone into a sharp, no-nonsense businesswoman.

There is also Bhola, a remarkably ambitious and intelligent young man. He is the only one from his basti who has managed to leave Chand Ghat and Banaras to pursue higher education in another city. However, at college in Ludhiana, Bhola hides his caste and identity. In his experience, he has realised that when he reveals his caste to anyone, they distance themselves from him and ridicule or humiliate him. But Bhola is determined to carve his own identity through his efforts, one that isn’t inextricably linked to his caste but his merit. I track his life to show how he manages to grow in his professional career. There are more such individuals whose experiences are encapsulated in the book.

Did you ever question your vantage as a reporter and whether you had the right to tell this story?

I am deeply aware of my background as someone from a privileged caste. I was extremely careful when I was writing the book, and I wanted to ensure that my voice did not overshadow that of the Doms’. I only inserted my voice when I needed to ask questions to propel the narrative forward. For this book, I also worked closely with a sensitivity editor.

However, I think it is important to understand that as a journalist, one’s loyalty is towards one’s job. When I began reporting on the community, I went there as a journalist. I felt that the community and other aspects of their lives had not been reported in detail. Their personal stories had not been documented and made accessible. The Dom men perform a highly specialised, caste-bound work that is dangerous and demanding, yet they are absent from mainstream conversations. Why? Even during the pandemic, the Doms fleetingly made news with relation to their crematory work. To my mind, their lives and experiences needed to be documented and compiled.

I believe if one writes from a place of empathy, if one is deeply committed to research, asking informed questions and listening carefully, and if one spends a considerable time reporting on a community, then the person is doing their job.

You have traced strong patriarchal biases that run through the community. While it starkly affects the women, what impact does it have on the men?

It certainly affects the men. There are many expectations placed on them. From a very young age, Dom boys (as young as 5 or 6 years old) are pushed out of their homes to go out and work at Manikarnika Ghat or Harishchandra Ghat–two cremation grounds in Banaras. They scavenge for kafan or shrouds–a glimmering cloth (available in hues of yellow, red or orange) that is draped over the corpses that are delivered to the cremation ground. The children sell the salvaged shrouds to shopkeepers for a small sum of money, who, in turn, wash, iron and package the shrouds and resell them to mourning customers.

The boys grow up watching corpses burn. They get bullied and beaten around at work. All this certainly affects them psychologically. Yet, they can’t remain within the safety of their homes. They have to depend on the dead to earn a livelihood.

They grow up to work as corpse burners. To cope with terrible working conditions, they drink copious amounts of alcohol and consume drugs. They must earn, since their families depend on it. The women, as you know, do not earn. The pressure to earn enough for a large family, then, is too much.

One of the corpse-burners told me that even when they injure themselves, they push themselves to work, otherwise “Choola kaisa jalega? (How will the kitchen run?)” Another said that he takes two or three hits of ganja before getting down to work. “If I take one or two shots, my mind eases up. Then I can burn eight-eight bodies in one go. Otherwise, the fire whips me so terribly, I cannot bear it.”

How would you situate the Doms, whose identity rests on caste and tradition, within the legal and social paradigm of the modern Welfare State?

You’re right that the Doms’ identity rests at the intersection of caste and tradition. They have ownership of the sacred fire which has supposedly been burning for centuries. It is believed that if a Hindu is cremated by this fire, only then can their soul receive moksha, liberation from the cycle of death and rebirth. Yet, the Doms continue to be treated as ‘untouchable’ by many caste Hindus.

Untouchability was outlawed in 1950. But the practice continues to exist in many parts of the country even today. While reporting in Banaras, for instance, I was told by the Doms about a shop-owner from a dominant caste. Sometimes, the Doms purchase items from his shop. During the transaction, the Doms are expected to place the money on the counter and stand back. If any change is to be returned, the shop owner asks them to cup their hands as he drops the coins into their palms. He does this to ensure that their fingers don’t accidentally touch his.

When it comes to accessing government schemes, the situation on-ground remains dire for the Doms, or has improved only by a margin. First, they live in a basti that is away from the city so, in a sense, they are away from the public eye. The people in the basti experience water shortage; many of the homes are too small to accommodate 6-8 family members. Most of the time, the Doms are not aware of the existence of government schemes. Even if they are, they don’t always have the necessary documents to avail themselves of schemes such as the Pradhan Mantri Awas Yojana, which provides affordable housing to low income families.

Bhola, for instance, feels that often it is the rigid bureaucratic system that prevents them from getting the full benefit of government schemes. Sometimes, the intended beneficiary does not receive the benefit at all because it is misdirected elsewhere—i.e. too many middlemen are involved.

(Somak Ghoshal is a writer and editor based in Delhi.)

Get exclusive access to new databases, expert analyses, weekly newsletters, book excerpts and new ideas on democracy, law and society in India. Subscribe to Article 14.