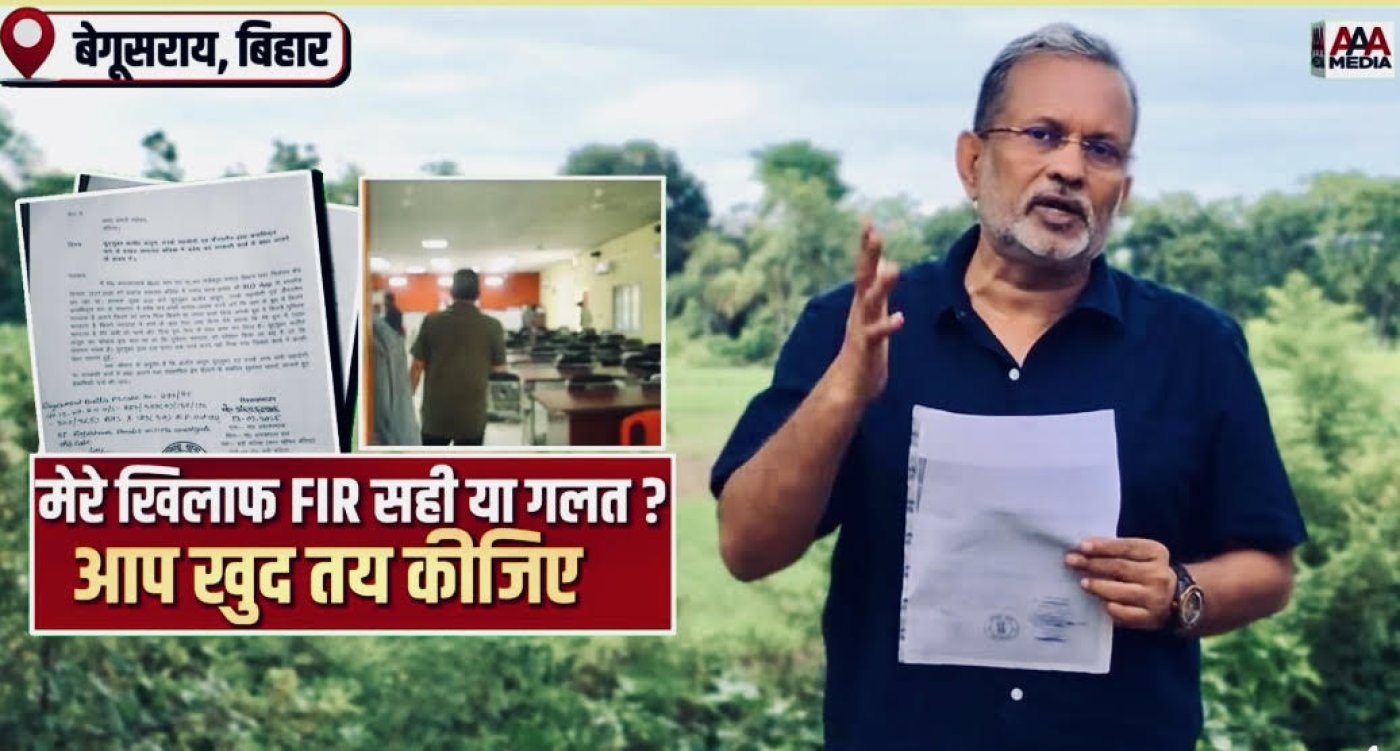

Delhi: Thirty minutes after he finished interviewing BLOs or booth level officers—in the Balia block of Bihar’s Begusarai district, around three to four hours by road from Patna—and left, Ajit Anjum, an independent journalist, got a call from local officials asking him to delete a video he had shot.

The video, which he uploaded to YouTube on 12 July 2025, showed BLOs uploading voter registration forms without photographs and other crucial details, chronicling irregularities in the special intensive revision (SIR) announced by the Election Commission of India (ECI) on 24 June. This constitutional body oversees the state and parliamentary elections.

Such a significant revision of the electoral rolls six months before the state assembly elections in Bihar triggered questions and concerns about motive and manageability, and ultimately deep distress and disenfranchisement of marginalised and minority populations.

On 15 July, Article 14 reported the chaos and confusion as the ECI attempted to revise Bihar’s electoral rolls for 78 million people in about three months, with voters struggling to organise the documents needed to register to vote.

The SIR requires everyone who registered after 2003—approximately 29 million voters—to submit one of 11 documents to establish their date and place of birth, while excluding the most common forms of identification—Aadhaar, PAN, and voter cards—often used to procure one of the required documents.

The Supreme Court, in response to petitions filed by opposition parties, has not stopped the revision, but warned the ECI against carrying it out in such a short period and suggested that it at least accept more documents, including Aadhaar.

First came a press note from the district magistrate of Begusarai, which said Anjum had filmed ongoing electoral work without authorisation, targeted people of a particular community, tried to make their private documents public, highlighted people of a particular caste in a way that creates social division and hatred, and spread misinformation that may potentially incite religious hatred.

Then, the Bihar police registered an FIR, a first information report, based on the complaint of a Muslim booth level officer (BLO) in Balia, whom Anjum had interviewed.

The BLO alleged Anjum asked him about the number of voters in his booth, how many forms had been distributed and received back, the number of Muslim voters, and had insisted that Muslim voters were being harassed, which, he said in his complaint, was not the case. The booth officer asked the police to invoke penal sections for interrupting government work for an hour and spreading communal hatred.

The FIR was registered on 13 July under the Bharatiya Nyaya Sanhita (BNS) for disobeying an order by a public servant, criminal (house) trespass, assault or criminal force used to deter a public servant from discharging their duty, promoting enmity between different groups, and uttering words with deliberate intent to wound religious feelings of any person.

Anjum, who has served as the managing editor of Hindi-language news channels such as News 24 and India TV, has a YouTube channel with nearly eight million subscribers.

After news of the FIR broke to widespread condemnation on 14 July, Anjum spoke with Article 14, saying he had anticipated an FIR after receiving calls from the sub-divisional magistrate and the block development officer, who had told him not to upload the video.

Anjum said he had steeled himself after the calls and was “neither nervous nor afraid” but rather weary of the tiresome process and procedures that would weigh him down and distract him from his work.

“When the SDM and BDO called to stop that video, I thought that if there was so much pressure before a video was published, some of my relatives called, then I thought there could be an FIR,” said Anjum.

“I made myself so mentally sound in the past 48 hours that I was mentally prepared,” he said. “I thought I would see what happened.”

“I’m neither nervous nor afraid, but there is concern because you have to look for an advocate. You could be summoned because of the FIR, for the investigation,” he said, “You have to leave work and then spend time dealing with the legal matter. That is what they want.”

Anjum said that he was planning to fly back to Delhi the next day, but he cancelled his ticket to see if he would be summoned. It was preferable to stay in Begusarai and wait to be summoned rather than leave for Delhi and then fly back to Bihar in a few days.

The adage that “process is the punishment” has become synonymous with the stories of journalists and activists who have faced FIRs and time in jail for being outspoken and critical of Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s government and other governments of the Bharatiya Janata Party in the state.

The decline of press freedom—mirrored in India’s low rank in the global press freedom index—and legal persecution of journalists have become so widely accepted and routine that it is now prevalent across the country, irrespective of which party is in power.

Article 14 has reported this decline in series over stories for at least four years (here, here, and here.)

India ranked 151st of 180 countries in the 2025 World Press Freedom Index, moving up eight places from 159th the previous year.

Bihar has a coalition government comprising the BJP, which holds the highest number of seats in the Assembly, and the Janata Dal United, whose leader, Nitish Kumar, serves as the chief minister.

We discussed how the Election Commission—acting through the state of Bihar—was now complicit in taking criminal action and attempting to silence a journalist, marking a new low for press freedom in India.

“It is a surprise,” said Anjum. “Election Commission, you are a constitutional body. You have set guidelines and parameters. I’m telling you where your guidelines are not being followed, but you are targeting me because clearly you don’t want the problems to be shown in public.”

“If you do an FIR on a simple video that is showing facts, then you are sending a message to reporters coming to cover the election and showing the reality,” he said.

Anjum reported from Hajipur, Muzzafarpur, and Patna, and visited Begusarai on the third day.

In the booth in Balia, Anjum said that he saw a lady supervisor uploading many voter registration forms, which contained only the people’s names and signatures.

The space for basic information, such as the mother's and father’s names and the Aadhaar card number, was blank.

Anjum said he questioned why incomplete forms were being submitted.

Anjum said the EC guideline is that the BLO would take two voter registration forms to the voter, giving one to the voter and returning with the other as a receipt. However, many BLOs told him they were not following this procedure.

Anjum said that the EC guideline is that a BLO would visit a voter three times, so no voter is left unvisited. However, many voters told him that no BLO is reaching them.

The concern is that many could be getting left out.

“They were in a panic about exposure and thought of doing an FIR, so I would be afraid,” said Anjum.

“Their objective is to make you afraid so you don’t do these kinds of stories.”

Voters who were registered after 2003 have voted in five Assembly and five Lok Sabha elections.

After it became apparent that voters would not be able to provide one of the 11 documents needed to register again, Anjum said the EC showed flexibility by saying the forms should be registered even if they cannot provide the required document at this time.

However, Anjum said, the BLOs were under immense pressure to complete the task within a stipulated amount of time and many half-filled forms were submitted.

Given that the EC has said that the sub divisional magistrate will scrutinise all forms between 1 August to 1 September, what are the chances that these half filled forms could be fixed; would the BLO go back and get the forms filled properly, and how would voters who currently don’t have any of the 11 documents would procure then a few weeks from now.

The ECI’s 11 approved documents: domicile certificate, passport, birth certificate, caste certificate, class 10th marksheet, forest rights certificate, land/house allotment certificate, family register, national register of citizens (wherever it exists), identity card or pension payment order issued to regular employee or pensioner, and identity card or certificate or document issued by government, local authorities, bank, post office, public-sector companies or the Life Insurance Corporation before July 1, 1987.

The Supreme Court has suggested including Aadhaar, but it remains unclear whether the EC will implement this.

If the EC included Aadhaar, Anjum said, then what would have been the point of this whole exercise, which set off this panic and turmoil?

The BLOs, Anjum said, were overworked, working 17 to 18 hours a day and often on the weekends.

“There is confusion and chaos,” said Anjum. “The BLO does not know what to do next and how to do it.”

(Betwa Sharma is managing editor of Article 14.)

Get exclusive access to new databases, expert analyses, weekly newsletters, book excerpts and new ideas on democracy, law and society in India. Subscribe to Article 14.