Mumbai: After at least three decades of warnings from climate scientists of lethal heat waves, large swathes of the northern hemisphere have experienced blistering temperatures this summer, alongside wildfires, losses to agriculture, and infrastructural collapses.

In north-west India, prolonged heatwave spells in April 2022 made it the hottest in the 122 years from 1901 to 2022. Meanwhile, five states—Uttar Pradesh, Bihar, West Bengal, Meghalaya and Nagaland—have shown “significant decreasing trends in southwest monsoon rainfall” in the 30 years from 1989 to 2018, even as some states received excess rainfall and torrential downpours, and floods, landslides and other extreme events were recorded elsewhere across the country, causing death and destruction of crops and property.

In Spain and Portugal, more than 1,700 have died due to extreme heat in 2022. Mid July, meteorologists warned of a “heat apocalypse” in western France where more than 25,000 people abandoned homes and holiday rentals to escape wildfires caused by a southern European heatwave. Similar fires ravaged parts of Spain, Portugal and Greece too, charring forests and farm land.

Spain introduced a heat wave naming and ranking system, and gave the world its first-ever named heat wave—Zoe—that hit Seville, capital city of the Andalusia region and home to multiple UNESCO heritage sites in the third week of July, with blistering temperatures touching 43.3 Deg C,

The United Kingdom had its hottest day ever, climbing past 40 deg C in Coningsby in Lincolnshire on 19 July, while the Arctic warms faster than the rest of the planet.

These are the latest in a series of simultaneous heat waves across the planet. Heat wave conditions in the north-west US and south-west Canada have recorded 2022’s highest temperatures in that region too, at 40.2 deg C in Lytton and 45 deg C in Oregon state, USA, and forecasters expected it to get hotter. More than 85 million Americans currently face heat warnings and heat advisories, as well as warnings of severe storms and flooding. A wildfire near the Yosemite National Park in California forced thousands to evacuate.

The Yosemite wildfire and the alarming dip in water level in Lake Meade, the largest reservoir in the US that’s located in southern Nevada and northern Arizona, showed up in satellite imagery displaying “a superheated planet that’s ablaze, desiccated and swamped in different areas all at the same time”, the Washington Post said on 27 July.

Earlier, on 15 July, climate scientist Peter Kalmus tweeted that alarm bells should be going off. “I wish everyone on Earth knew how genuinely "off the charts" key planetary trends are right now, and how abnormal and critical it is,” he wrote. The tweet received 141,000 likes.

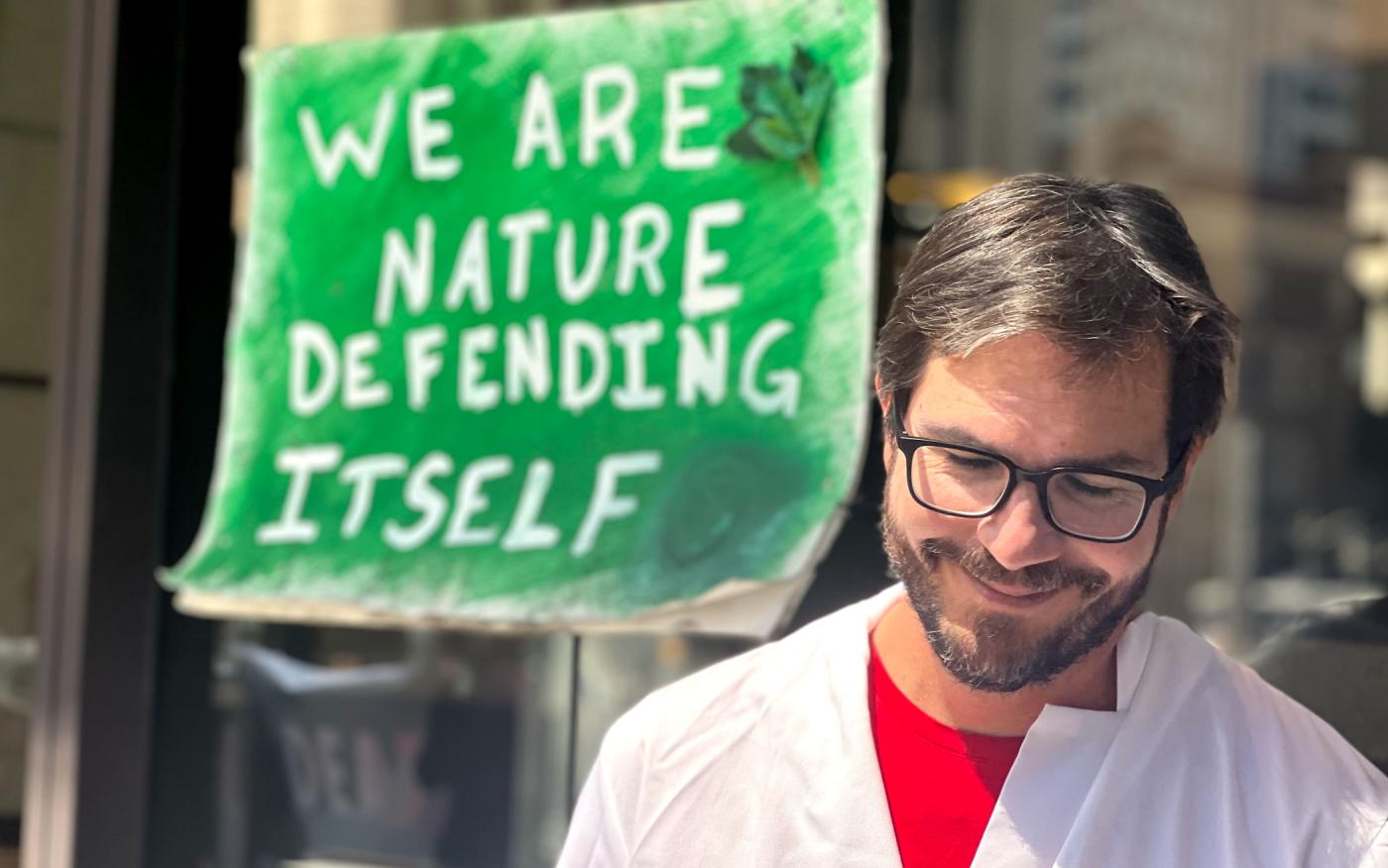

In April, Kalmus chained himself to a steel door handle at the Los Angeles office building of a multinational bank with huge investments in fossil fuel infrastructure. He and three others were arrested, and booked for trespassing.

Before he was detained, he spoke about trying to save the earth for his children, breaking down on camera. “I’m here because scientists are not being listened to,” he said. “I’m willing to take a risk for this gorgeous planet.”

According to the latest (2022) report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), existing and currently planned fossil fuel projects are in danger of rendering unattainable the target to limit global warming to below 2 deg C, preferably to 1.5 deg C, compared to pre-industrial levels, an undertaking of the legally binding international treaty adopted at the Conference Of Parties (COP) in Paris in 2015.

A climate scientist for 17 years, Kalmus responded to the simple evidence that burning fossil fuels is the single largest contributor to global warming by cutting his own emissions by 90%, reducing his carbon footprint to about one tenth of the US average.

He helps individuals and organisations use less fossil fuel, he grows some food, has been a vegetarian since about 2010, and wrote an award-winning book, Being The Change: Live Well And Spark A Climate Revolution, in which he discusses real life solutions that involve consuming no more fossil fuels than absolutely necessary.

Kalmus also founded ‘No Fly Climate Sci’, a worldwide collective of academicians and scientists committed to flying as little as possible.

Kalmus, who holds a PhD in physics from Columbia University and a BA in physics from Harvard, is a climate scientist at the Jet Propulsion Laboratory of the US National Aeronautics and Space Administration, where he uses satellite data and models to study the rapidly changing earth, focusing on biodiversity forecasting, clouds, and severe weather. Kalmus spoke to Article 14 on his own behalf, independent of his work with NASA.

You were among climate scientists worldwide who courted arrest this summer to warn the world about the death of the historic Paris agreement to limit global heating by 2100 to 1.5 deg C. Why did your civil disobedience for climate action particularly target banks?

Basically human society is set up to ensure that fossil fuels keep flowing, our economy is built on that, and part of that system is the financial system. We were looking for a place to raise awareness of the need to stop building new fossil fuel infrastructure altogether. This is what the IPCC report made very clear, and this would be my opinion, and this is why scientists are being ignored.

We've made it very, very clear that to avoid cataclysm—the end of civilization as we know it–we need to stop building new fossil fuel projects right now. And those new fossil fuel projects have a 40-year lifespan. It is insanity to be building more now when we need to be wrapping down what we already have.

Without the financial support of banks, new fossil fuel projects cannot be built. And so we decided to pick a theme to raise awareness about going forward with a lot more climate action, to also look at the financing of fossil fuel industries.

The fossil fuel industry itself is also something we want to highlight in civil disobedience actions. World leaders, politicians who are basically in the pay of the fossil fuel industry, would be another good place to focus civil disobedience actions on. So take your pick. What we really need is for everyone to realise what's going on, that if we continue burning fossil fuels, as a species, we risk losing everything.

You’ve written that if everyone could see what you see coming, society would switch into climate emergency mode straight away, and end all fossil fuels in just a few years. Your book discusses how you reduced your own personal emissions by 90%. What do these two processes actually entail?

If we decide that this is a life or death issue, that it's genuinely an emergency, then we would stop using energy. I mean, in the Global North, there is a tremendous amount of energy that is wasted—the rich have their private jets and yachts and their giant homes that they have to heat and cool, and they consume a huge, huge amount they don't really need. If we shave off all of that excess energy use, that would be a very good place to start.

Then we need to divert fossil fuels to the stuff that we need, to actually survive and not die. That’s things such as the food system, basic transportation, basic heating and cooling every building. And that's pretty much it, right?

Simultaneously, if we build our renewables, then the stuff that can run on that electricity can keep going.

But we want to, especially in the Global North, in the countries that are wasting a lot of energy, reduce energy use overall so that the build-out of renewables doesn't have to go up as high before we transition to 100% renewable electricity.

That will be the first few years, just realising that this is a life or death thing, that the climate emergency is irreversibly and very quickly degrading the life support systems of our entire planet, which could lead to catastrophic shortages of food and water, infrastructure failures, warfare over lack of resources and huge numbers of immigrants trying to move out of places that are too hot for them and that don't have enough food and water.

It sounds crazy to say, for example, ‘give up commercial aviation’. It sounds crazy because the global rich don't realise right now that this is a life or death emergency.

By ‘emergency mode’ I mean we basically shift all of our energy use to only using energy to survive. For that we have to completely rethink our economic systems. Right now, most of the GDP goes to the ultra rich and that's why we need constant growth. So there has to be a way to stop the ultra rich from hogging all that energy, hogging all the wealth. That makes redistribution of wealth absolutely necessary to resolve this crisis.

After that initial phase of coming out of this insane, excess energy use by a few and insane wealth collection by a few, then we'll have to do the harder stuff. That involves learning how to feed billions of people on this planet without fossil fuels, which means with different kinds of fertiliser use. Humans can't, for example, just be dumping all of our waste. Basically our urine is fertiliser, and so is other kinds of waste from us. We're just dumping that into the ocean right now. We have to rethink that.

We have to stop eating so much meat. Twenty percent of global heating is caused by industrial animal agriculture. We have great vegetarian options now, at least here in the United States. You can still have a burger that tastes great but is actually made from plant-based ingredients.

What was your own personal roadmap for 90% lower emissions at an individual level?

First, if you want to reduce your own emissions, it’s a good thing, but I would say don't ever let that substitute political action pushing for systems change.

There are many different levels of risk in civil disobedience and for me, the climate action at JPMorgan Chase was extremely low risk, as a white scientist in a rich city. All I did was chain my wrist to a door handle, and I was charged with trespassing. But even low level risk actions like that can potentially have impact in terms of creating the social sense of urgency over climate change.

For me, reducing your personal emissions can be a good thing if you're very worried about this and you don't want to feel like you're contributing to the problem so much. But it's not going to change things fast enough.

The three main things I did was first, I understood where my emissions were coming from and then second, I took care of the two biggest sources of emissions for me—flying and eating meat. There were other things too, like driving less and biking more; buying less stuff; and so forth.

Not ever flying is a little inconvenient. I had to kind of get my colleagues used to the idea that I wouldn't be flying to conferences. On a personal level too, travel is more difficult. Over the next few years, I am considering some sort of sailing trip to Europe, and I’ll spend the whole summer there.

Not eating meat was actually really easy. I've been thinking about it for a long time anyway just on the basis of animal cruelty. I follow a meditation practice called Vipassana, and one of its moral principles is to not kill. For several years, I’ve been trying to go deeper into the practice and once I’d tried vegetarianism for a month, I realised I felt fine. Actually I feel better, I have more energy. I have been a vegetarian since about 2010.

For the developing world, and particularly for India and China where half all our energy will continue to be derived from fossil fuels in the near future, fossil fuels are really at the heart of economic growth. So how do we reconcile climate science and climate action with basic human aspirations for a way out of poverty?

We need an international fossil fuel non-proliferation treaty. The nations that have created the most emissions over the course of our history per capita should reduce faster. The United States is at the top of that list.

The reason I say we need wealth redistribution is not just because I think it's more fair to not have such disparities, but also because it’s actually just absolutely necessary for coming out of the climate emergency.

For example, for us in the United States to wrap down the fossil fuel industry will mean that fossil fuels’ supply will have to reduce every single year, less fossil fuels next year than this year, and so on. If we did that and if we allowed the market forces to do that, what would happen to the price of petrol? It would skyrocket, the working class people in the United States would rebel against the new climate policies. They’d say they can't afford to get to work, can’t afford to take their kids to school, let the planet burn. I guess that's what they're already saying.

So, that reduction in fossil fuel supply has to essentially be subsidised by the ultra rich who have been causing the most problems. So there has to be some kind of rationing, like everyone can have this much fossil fuel in a year and it's going to be at a fixed price. We're going to tax the rich to pay for that so that the price stays fixed over the next 10 years as we wrap down the industry.

That’s in the United States. This same principle applies to different nations. If the wealthier nations do not reduce their energy use and their carbon emissions, how can they expect a country like India to start reducing, nations that have contributed a tiny percentage to this crisis. The developed nations absolutely have to lead, there has to be a justice component to this that recognises that this is a global problem that was caused primarily by rich nations, and so rich nations have to lead in terms of carbon emission reductions, and they have to pay losses and damages to poorer nations.

A lot of this is just common sense.

Should Brazil be allowed to just say they’re going to cut down the Amazon forest because we want the economic development that it brings or is the Amazon rainforest something that belongs to everybody? These are questions that we have to start grappling with as a species as we go deeper and deeper into this very serious global problem.

I don't know how we're going to transition into a sense that we're all in this together and that we have to share, and we have to come out of this together. It seems like we're heading in the opposite direction, where the rich people, the billionaires and the rich nations, are just building walls and saying we're going to do everything we can to just keep hoarding to ourselves.

So it almost feels like there has to be some kind of revolution where the working class says wait a second, this is not okay, you guys don't get to keep everything while we're starving, our children's futures being burned in front of our eyes. I don't know how we get to that.

But if I were a billionaire right now, I would be pushing very hard for a more equitable distribution of wealth, just for my own sense of safety. Because if things break down past a certain point I don't think the billionaires are going to be safe, because there will be so much pent up rage.

So that's just my opinion. I don't know exactly how we transition. But to me, it couldn't be more clear that we do not come out of this without a real sort of change in how we think about wealth, how we think about hoarding and how we see that we’re all in this together.

Is the world witnessing a keener urgency now in climate action because the West is experiencing these record temperatures? What would you say about that hypocrisy to people in India or in the global south?

I've been a climate activist for 17 years and I saw this coming because I was reading scientific papers. I thought that if you see something really dangerous coming, and it's going to take human civilisation a long time to transition and avoid that, then we should start early. That totally didn't happen. Up until a couple of years ago, I was completely ignored. We kept saying it, kept sounding the alarm, and kept getting laughed at.

It’s very sad, but humans are not good at long term thinking. And in general humans don't have a lot of compassion, so they tend to not care that much when something is hurting other people.

We need to grow up as a species and become more compassionate, start thinking more in terms of the long term which is basically a form of compassion, because you're trying to keep things good for people that come after you, for younger people. This particular consumerist, capitalist profit-above-everything-else culture is basically completely devoid of compassion.

I try to make the most of climate disasters in the Global North, partly out of concern for most affected peoples who will be paying the highest price that mostly live in the Global South. As an activist in the Global North, anything that makes humanity as a whole and especially rich nations start to act on climate change sooner rather than later to me is a good thing.

Can you tell us a little more about that? What is it like to be in a position where your work is seen as unwarranted panic or hysteria, even when you’re citing evidence-based science?

It takes a lot of compassion to keep going because you're just trying to help, save as many lives as can be saved by sending an alarm, and people keep insulting and mocking you. It would be easy to give up, but you can't do that because you think of all the children, you think of all the trees, you think of all the animals in the ocean and the places that you love, and you keep doing it for those things. I keep going also for my own kids. What helps me a lot is to always keep in mind that I'm not doing any of this for myself.

If you really think about it, every time you take a breath, you owe that to the earth and you should be grateful that you can just take that. Every time you eat something, it’s the same thing. Every time you drink water. We owe our existence to this amazing planet, this amazing biosphere and it is a form of love that we're here. So that, to me, is the most sustainable way to keep fighting as hard as you can, even when people ignore you.

COP 26 president Alok Sharma was in India, and the environment minister emphasised the need for timely delivery of finance and technology support to developing countries to combat climate change. What is this technology that will assist our net zero ambitions, what is going to be an adequate shopping list?

I think everyone knows the three key technologies—wind, solar and batteries. You should be transferring all your buses, rickshaws and autos to electric as soon as you can. You should be building out solar.

Equally important, whatever technological support is available at this point, like all solar technologies, they should be open access. It is such an emergency now that we cannot allow unusable patents and profiteering on these technologies, but we need to make them better at the same time, and spread them around the world super, super fast.

You're gonna need robust electrical grids. If I were India, I would be trying to adopt policies for local scale energy production—every community has their data, their solar panels and batteries so that you're much more robust against blackouts. One real danger I see, as extreme humid heat gets worse and worse over the coming years, as more air conditioning is added, I’m worried that in the worst heat waves you're gonna have a blackout. Millions could die. That infrastructure needs to be distributed to scale so that it's very resilient.

(Kavitha Iyer is a senior editor with Article 14 and the author of ‘Landscapes of Loss’, a book on India’s farm crisis.)