New Delhi: “As a journalist yourself, you know that one or two FIRs (first information reports) against a reporter is not news these days, but this is unbelievable.”

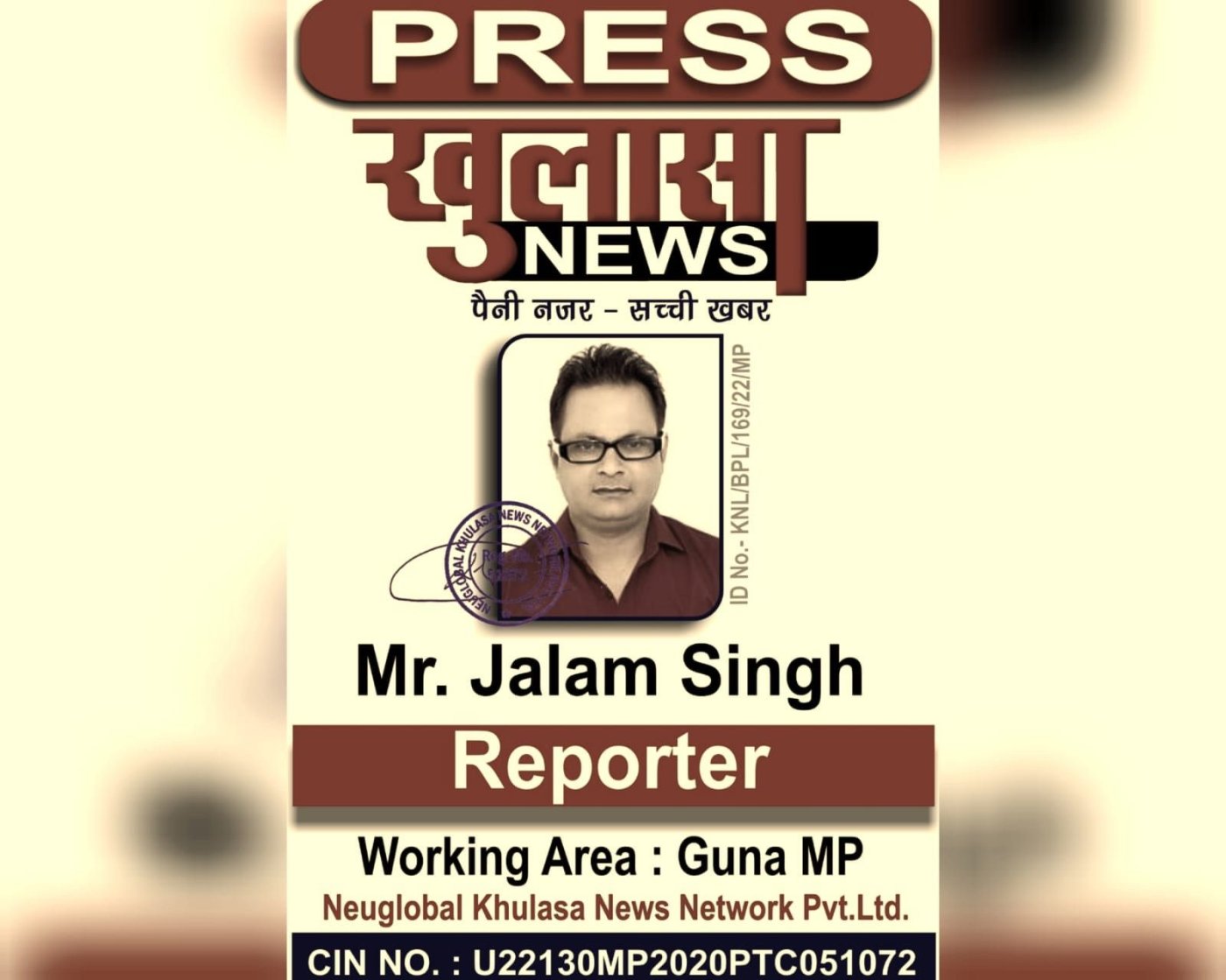

That was Suresh Acharya, the founding editor of Dainik Khulasa, a news website based in Bhopal, Madhya Pradesh (MP). He was discussing what the police had done with his reporter, Jalam Singh, 35, who was arrested on 13 September, four days after he reported about a viral video of a Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) state minister with a woman, which he described as “highly objectionable” and “crossing all bounds of obscenity”, and has been in jail since.

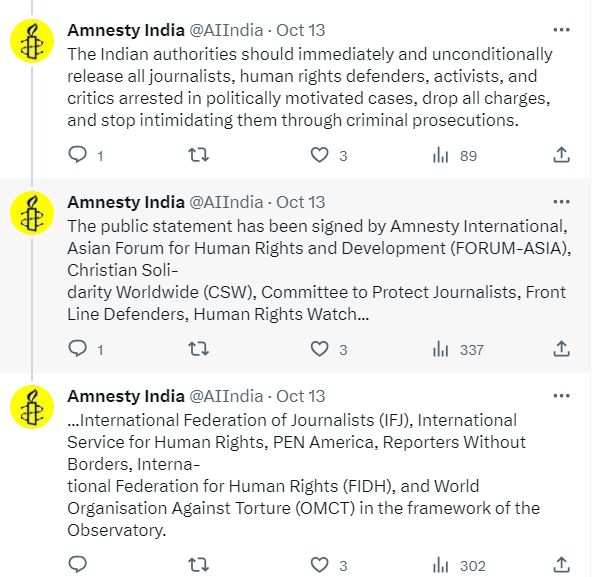

Singh’s arrest is among the latest examples of State intimidation of journalists in India, where press freedom has been under growing threat. On 14 October, Amnesty International and 14 global organisations called on Indian officials to stop the misuse of the country’s laws against journalists and others.

Singh’s case is unique because it appears to be a new benchmark, given the number of criminal cases he now faces. If convicted, he faces a maximum jail term of three years.

Close to a month had passed since the MP police arrested Singh when Newslaundry, an independent website, reported how they filed 11 first information reports (FIRs) against him over four days, bringing attention to an extraordinary misuse of the state machinery, which the 42-year-old Acharya described as “unbelievable.”

The FIRs accuse Singh of “provocation intending to cause riot”, extortion, forgery and defamation, under the Indian Penal Code, 1860.

Article 14 has not independently verified the number of FIRs, the figure reported by Newslaundry. Acharya said Singh, who lives in the district of Guna, phoned and told him the police had registered 11 FIRs against him and policemen from different police stations were “hounding” his family. The editor said policemen who questioned him about Singh also told him there were 11 FIRs.

“It is like he is the most dangerous criminal in the country,” said Acharya. “It is no longer safe to be a journalist in this country. Have you heard of 11 FIRs?”

Acharya said that after FIRs started coming, Singh moved for anticipatory bail, but a Guna district court judge rejected it. Fearing the fallout for his family, he surrendered and moved the Gwalior bench of the Madhya High Court.

Vijay Khatri, the superintendent of police for Guna, said he had recently joined and did not know about Singh's case. We sent him the information, but he did not respond. The former SP, Rakesh Sagar, told Newslaundry that this “action has been taken at the station level”.

A New Benchmark In Intimidation

Filing a series of FIRs appears to be a tactic that police use to intimidate journalists or dissenters, said experts, but the sheer number filed against Singh for this story about a state minister’s reportedly “obscene” sexual video is unprecedented.

Till the end of 2022, the Uttar Pradesh police had registered six cases against fact-checker Mohammad Zubair, and the Delhi police had two. In 2023, the UP police added one more.

The UP police have registered eight cases against social activist Javed Mohammad in Allahabad and have kept him in jail for 16 months using the National Security Act, 1980, which allows detention without charge for upto a year.

The Jammu and Kashmir police activated four pending cases against Kashmiri journalist Fahad Shah in 2022 and jailed him for over 20 months.

“The sudden registration of multiple FIRs in quick succession on largely petty allegations cannot be a mere coincidence and suggests that there may be an unfortunate pattern of motivated cases being registered against the journalist," human rights lawyer Vrinda Grover said about Singh’s case.

“The law and legal machinery are being weaponized against journalists who speak truth to power, which really highlights the dangerous proximity between the political apparatus and the police machinery,” she said. “If journalists have to lose their personal liberty simply for doing their job and reporting, this would have far-reaching consequences not only for journalists but for democracy.”

Violation Of Arnesh Kumar Guidelines

While the police registered the first FIR against Singh close to midnight on 7 September, the chief minister, earlier that day, promised to enact a law to protect journalists. These related to home loans, premium on health insurance, educational loans, honorarium for senior and retired journalists, and compensation for families in case of death.

The eight FIRs shared by Newslaundry have been registered under sections 153 (provocation, with an intent to cause riot), punishable with a maximum imprisonment of one year, 384 (extortion), punishable with a maximum imprisonment of three years, 385 (putting a person in fear of injury to commit extortion), punishable with a maximum imprisonment of two years, 469 (forgery for the purpose of harming reputation), punishable with a maximum imprisonment of three years. Some complainants were clearly linked to the BJP.

Two complaints were registered by third parties who said Singh maligned the minister’s image and accused him of blackmail, and six by people who said that Singh had blackmailed or extorted them.

One woman who filed a complaint of extortion said she did not know the complainant, but she signed some papers after she was called to the police station and told she would get her pending dues from a government welfare scheme. A BJP official who filed a case for extortion said that he did not know Singh or remember the case.

The Arnesh Kumar guidelines laid down by the Supreme Court in Arnesh Kumar vs The State of Bihar (2014) say arrest should be an exception in cases with less than seven years of punishment.

“I don’t understand why he has been arrested,” said advocate Shahrukh Alam. “This is a complete abuse of process procedurally and substantively in terms of the ingredients of the offence. It is just bizarre.”

Why Register The FIR

Should the police have registered a series of seemingly engineered FIRs against Singh?

Under section 154 of the Criminal Procedure Code, any person can give information to the police for a cognisable offence, and the Supreme Court’s guidelines in Lalita Kumari vs Govt of India (2013) make it mandatory for the police to register an FIR. The few exceptions requiring a preliminary inquiry include matrimonial disputes, commercial offences, medical negligence cases, corruption cases, and cases where there are long delays in reporting the matter.

Acharya said they had long demanded that the police not register FIRs against journalists without conducting a preliminary investigation, but the state had never followed through.

Earlier this year, the BJP government in UP made that rule for business owners and entrepreneurs while setting up a mechanism to track “negative news” and verify the facts of such articles because they “tarnish the image of the government”.

Even if there is no preliminary inquiry requirement, Alam said the police don’t have to register an FIR if the complaint does not make out a prima facie case, like, for instance, in the cases where the third parties filed the complaints alleging the Singh had maligned the minister’s image.

“If I go to the police and say I have seen this video being circulated, I think that in doing this, this journalist is extorting the minister. Then, on the face of it, there is no offence made out,” said Alam.

'The Poor Fellow'

Recalling the Supreme Court clubbing the FIRs against Mohammad Zubair registered in UP and transferring them to the Delhi police, senior advocate Indira Jaising said that eleven cases on unconnected issues against one journalist appeared problematic.

“Even that remedy of combining all of them appears to be a bit problematic,” said Jaising.

“The poor fellow, how many FIRS will he move for bail in? Each one of them, if it is cognisable, he’ll have to move for bail,” she said. “It is ridiculous.”

The other “subliminal thread” running through the FIRs was that journalism is being used to blackmail people, said Jaising.

“To randomly accuse a journalist of using the pen to blackmail people is nonsense,” she said.

Not convinced that a preliminary inquiry by the police before registering an FIR would offer any real protection, Jaising said, “There should be an independent review when it comes to complaints against journalists because there is a fundamental right to free speech and the right to disseminate and receive information,” she said.

'He Crushed Him'

Even though the video was already going viral in Guna, and they had the clip where one could see the panchayat and rural development cabinet minister, Mahendra Singh Sisodia, Acharya said they did not name him.

Despite requests for the video for verification, Acharya did not send it, saying it was “so obscene” that he did not want to share it with a woman reporter like me.

Singh’s story said the matter had reached the party's high command and could impact the minister’s chances of getting a ticket in the state election in November.

“We don’t publish anything without evidence,” said Acharya. “He is a very good reporter. His work is usually on the front page.”

Sisodia, who served as the labour minister in the Congress government of former chief minister Kamal Nath, was one of the 22 state lawmakers to leave the Congress for the BJP in March, triggering a political crisis that allowed the BJP to come back to power.

Article 14 sought comment from Sisodia, who did not respond to calls or messages.

Acharya said he received a call from an unidentified man asking him to fire Singh. While he did not know who it was, the editor said it “must have been” an associate or aide of the minister.

“I said, but how can I fire or suspend someone who has not done anything wrong?” he said. “I said, I cannot do it, and I won’t do it.”

Singh’s lawyer and wife declined to comment about his case.

Acharya said they were scared because the minister was “very powerful” with much influence, and he may have reached a compromise with the family in the wake of the bad publicity and the caste-related animosities the FIRs had caused.

“He is the Bahubali (strongman) in the area,” said Acharya. “No one can say anything against him. My reporter did, and he crushed him.”

Singh’s wife, Suman, told Newslaundry that his family was “very distressed” and were struggling to put the bail amount.

On a Guna district court judge rejecting anticipatory bail for a journalist, Acharya said, “He should have got the bail, but given the minister's influence, I’m not surprised. Or it could have just been the judge thinking so many cases have been registered in different police stations.”

Given the outsized issue of caste in the state, Acharya said the FIRs had caused a lot of ill feeling between the minister’s community (Thakurs) and the reporter’s community (Kirar—other backward classes—same as that of chief minister Shivraj Singh Chauhan), which did not bode well so close to the election in November.

Policemen who came to ask him questions about Singh after the FIRs were also from the Kirar community and unhappy about what had occurred, according to Acharya.

“Here, everything is about caste,” he said.

The Assault On India’s Free Press

The 11 FIRs against Jalaam Singh came to light on the heels of the Delhi police conducting sweeping raids at the homes of journalists connected with the news portal NewsClick, whose editor, Prabir Purkayastha, has been accused of receiving funds for positive coverage about China. The police seized phones and laptops and detained some reporters.

While the Enforcement Directorate (ED), the economic offences wing of the Delhi police and the income tax department were already investigating Singh without producing a chargesheet for two years, the Delhi police special cell registered another case against him and the NewsClick’s HR head Amit Chakraborty under the Unlawful Activities Prevention Act (UAPA), 1969, India’s anti-terror law.

After the police arrested them under the anti-terror law, the Central Bureau of Investigation (CBI) raided his home and office and filed another case against him under the Foreign Contribution Regulation Act (FCRA). The Delhi High Court rejected their application challenging the trial court order remanding them to jail. Their challenge to the FIR (first information report) and arrest are pending.

Of the 16 journalists charged under the UAPA since 2010, seven are in jail (four are from Kashmir), the Free Speech Collective said in October 2023. In 2020, they said 154 journalists in India were "arrested, detained, interrogated or served show cause notices for their professional work", 40% of them in 2020.

Article 14 has extensively reported how perilous the environment for press freedom has become in general and for independent journalists in particular (here, here, here, here, here and here) as the State deploys a variety of laws, including those meant to prevent terrorism.

Since 2018, there have been at least 44 summons, raids or notices to media companies and journalists by investigative agencies controlled by the union government, Newslaundry (itself raided in 2021) reported in May 2023.

Last year, the Committee Against Assault on Journalists, an advocacy group, reported that 48 journalists were physically attacked in UP, 66 were booked or arrested, and 12 were killed.

‘Become Like Godi Media’, Or Else

As the editor of a website that he said exposed crime and corruption of the powerful, Acharya said he had steeled himself against the angry phone calls he received from officials and politicians.

Asked him if there was a difference between the Congress years (the party ran Madhya Pradesh for 15 months, from December 2018 to 20 March) and the BJP, in power for two decades, Acharya hesitated, saying he did not want to sound in favour of one party and against another.

Acharya added, however, that there was no denying persecution was worse. “It used to happen, but I don’t think it is to the extent it is now,” he said.

“They put FIRs on people to put pressure on them so they too become like Godi media and do what they say,” said Acharya. “There is now a constant fear in your heart and mind that if you write against the government or politicians, they will come at you with FIRs.”

“The idea is to act against a few people so that the entire journalist community is frightened, and they will do what they say,” said Acharya, his assessment mirrored in India’s declining press freedom rankings.

India’s rank on the World Press Freedom Index, compiled by global media watchdog Reporters Without Borders (RSF), dropped 11 places over a year to 161 of 180 countries in 2023 and 39 places from 2010, ranked 122 of 178.

India’s rank was 150 in 2022, 142 in 2021 and 2020, 140 in 2019, 138 in 2018, 136 in 2017, 133 in 2016, 136 in 2015, 140 in 2014 and 2013, when the Congress-led United Progressive Alliance government was in power.

India’s 2023 rank is its lowest since 2002 “because of increasing impunity for violence against journalists and because internet censorship continues to grow”, Reporters With Borders said.

Acharya, who has a degree in organic chemistry from Barkatullah University in Bhopal and is pursuing his master’s in journalism from Atal Bihari Vajpayee Hindi University, Bhopal, said he encouraged all his reporters to get journalism degrees.

But what it meant to be a journalist had changed, said Acharya.

“The status and respect that a reporter used to have is gone,” he said. “I think some politicians and powerful people have used social media to wage a war against the media. They have destroyed what it meant to be a journalist.”

(Betwa Sharma is managing editor of Article 14.)

Get exclusive access to new databases, expert analyses, weekly newsletters, book excerpts and new ideas on democracy, law and society in India. Subscribe to Article 14.