New Delhi: Atta ur Rehman was at work in the south Delhi area of Tughlakabad on the morning of 30 April when he received a phone call from his frantic children, informing him that a bulldozer had arrived to tear down their home.

Rehman, 38, a tailor, left his little shop and rushed to his two-room, brick home built 11 years ago. Backhoe excavators, escorted by police, had entered the narrow lanes. Rehman, his wife, two daughters and son began to collect their belongings in a desperate attempt to save what they could. By evening, their home had been torn to the ground.

When we visited the demolition site, we saw Rehman sitting distraught amid a pile of rubble that used to be his home.

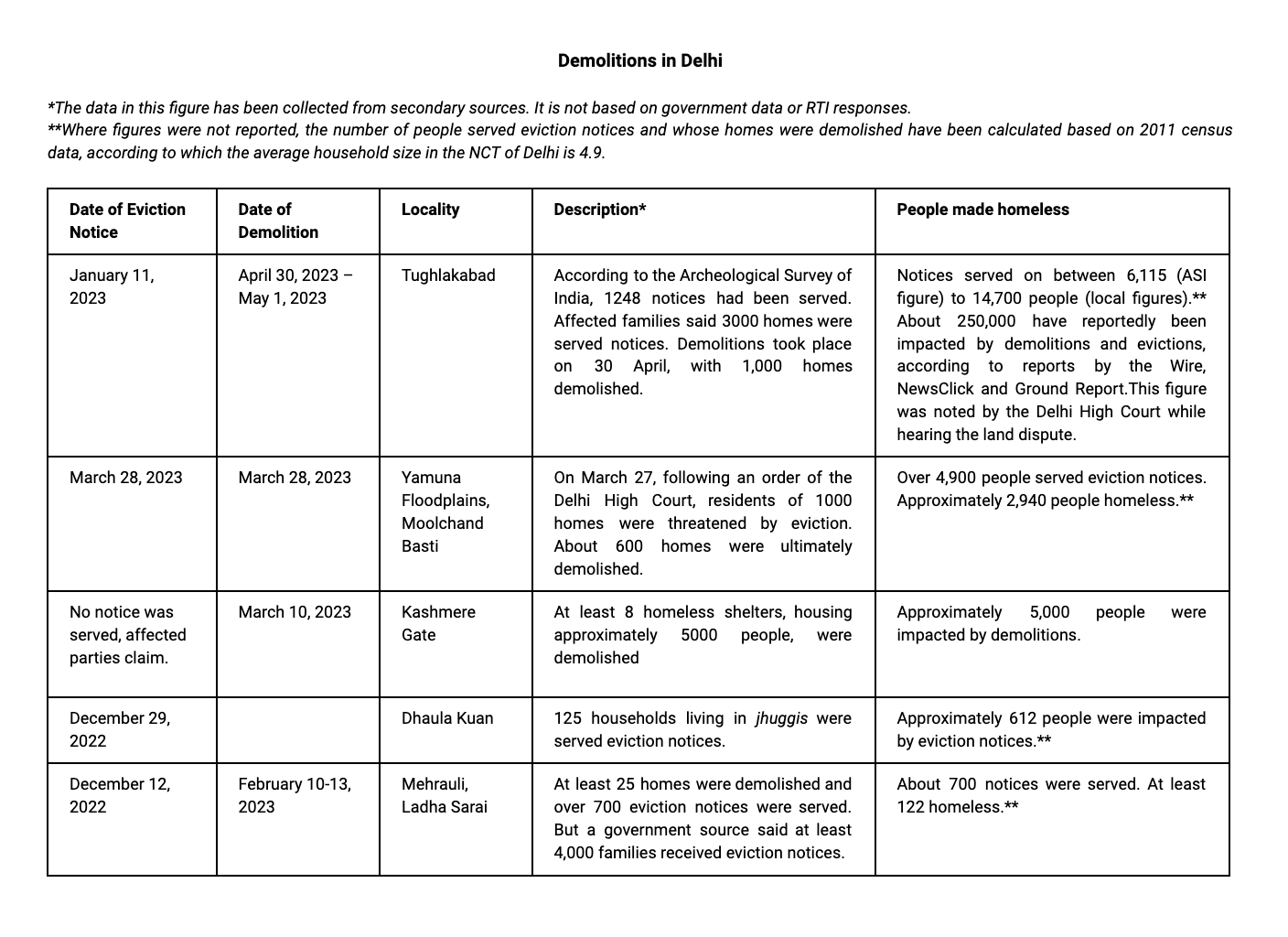

Similar scenes of devastation and trauma have played out in four working-class neighbourhoods, largely slums, over three months, as the Municipal Corporation of Delhi, run by the Aam Aadmi Party (AAP) and the union government, run by the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) implement a “beautification” plan to doll up India’s capital, as it prepares for G20 summit meetings scheduled on 9 and 10 September.

This is not the first time the Delhi administration has undertaken large-scale demolitions ahead of an international event. Evictions before the 2010 Commonwealth Games displaced about 200,000.

Despite established law (here and here) requiring prior notice before demolitions and rehabilitation plans, at least 1,600 homes have been demolished and about 260,000 are reportedly homeless after four major demolitions over three months, with notices often served as demolition squads moved in.

On 12 February 2023, 57-year-old Faiman Isra’s family looked on in shock as backhoe excavators tore down their home in south Delhi’s Mehrauli, home to several UNESCO heritage sites and one of India’s oldest continuously inhabited urban settlements.

The G20 summit is a premier international forum for economic cooperation. The annual summit, chaired this time by India, is attended by heads of states and other delegates, many of whom are scheduled to go on a heritage walk in Mehrauli in September.

[[https://tribe.article-14.com/uploads/2023/05-May/06-Sat/IMG_5570.jpeg]]

The demolition of Isra and Rehman’s home is unfolding as a Rs-1,000-crore citywide makeover disproportionately targets working-class and underprivileged neighbourhoods, in a city of 16 million where only 23.7% are estimated to live in “planned” neighbourhoods, the rest in slums, villages and unplanned or unauthorised settlements.

On 24 February 2023, Prime Minister Narendra Modi asked G20 finance heads to focus on helping the “most vulnerable”, even as his government carried out demolitions housing Delhi’s poorest, including those in government-run homeless shelters, some of which were demolished as well.

In the basti adjacent to the Tughlakabad fort, demolitions continued into the night amid heavy rain, with affected residents complaining about the use of harsh police force.

Bipasha Mandal, a domestic worker in her twenties, recounts a female officer pulling her hair as bulldozers tore down her home.

Promises, Laws Broken

The demolitions have forced much trauma on thousands, despite official promises that they would not.

“No one residing at a location related to infrastructure for the G-20 summit should be removed in a callous and inhuman manner, without being provided assistance,” Delhi’s lieutenant governor Vinai Kumar Saxena said on 31 January 2023.

“Everything we ever earned, we put towards this home and now we’ve been left with nothing,” said Isra, who had invested Rs 10 lakh over 35 years to build a three-room home for her joint family of 12, including her husband and four children and their families.

Between 10 to 13 February, the Delhi Development Authority (DDA), which comes under the union government, razed at least 25 houses in Isra’s locality including apartments, independent homes and jhuggis or informal settlements in the presence of police forces.

The demolition drive came to a halt on 14 February, when the Delhi High Court ordered a stay. A day earlier, the lieutenant governor Saxena told the DDA to stop the demolitions, until further instructions, after he met residents.

More recently in Tughlakabad, approximately 1,000 homes were torn down, starting on 30 April. But Lakshman Singh, a member of the community who had surveyed the locality before the demolition, claimed the number of homes is closer to 3,000.

These demolitions are the most recent in the spate of evictions across the country, many targeted at the Muslim minority (here, here, here and here), with the JCB backhoe excavator becoming a symbol of such demolitions.

This manner of demolitions—without hearings, notices or translocation opportunities—violates a series of court judgments and the city’s own laws, as Article 14 has reported (here and here).

[[https://tribe.article-14.com/uploads/2023/05-May/06-Sat/IMG_5760.jpeg]]

Section 5B of the Public Premises (Eviction of Unauthorized Occupants) Act, 1971 requires an estate officer to serve a minimum seven-day notice requiring an occupant to either demolish the unauthorised structure, or explain why it should not be demolished.

Section 247 of the New Delhi Municipal Council Act, 1994 says no order of demolition shall be made unless the person has been given, by means of a notice served, “a reasonable opportunity of showing cause why such order shall not be made”.

Similarly, section 368 of the Delhi Municipal Corporation Act, 1957 states that even if the commissioner orders a demolition, the building must be vacated within a period specified in the order, “not being less than thirty days from the date of the order”. The demolition must be undertaken “within six weeks after the expiration of that period”.

Even if a building is deemed “unfit for human habitation”, The Slum Areas (Improvement and Clearance) Act 1956 prescribes the same norms of a 30-day notice period and a time-bound demolition subsequent to that.

In Sudama Singh & others vs Government Of Delhi 2010, the Delhi High Court held that before any eviction, it was the duty of the State to survey all those facing evictions and to draft a rehabilitation plan in consultation with the “persons at risk”.

In some neighbourhoods we visited, notices were indeed served, except that those notices came as the JCB’s arrived. There was no evidence of rehabilitation plans.

Notices Served With Demolitions

Between December and April, the DDA served demolition notices to residents in many area—Mehrauli and Gosiya colony on 12 December; Tughlakabad on 11 January, near Kashmere Gate on 10 March; and on 28 March in Moolchand basti at Rajghat (you can see Article 14 videos of demolitions here and here).

Heera Lal, a construction worker, whose makeshift home on the Yamuna floodplains was one of the homes demolished on 28 March, explained how demolitions and notices were served together.

“Around 3 pm, DDA officials and police forces arrived at the basti and began demolitions while serving demolition notices,” said 40-year-old Lal.

In some places, such as Dhaula Kuan, 125 households in jhuggis, as slums are locally called, were served demolition orders but got temporary respite with stay orders. Dhaula Kuan’s basti residents approached the Delhi High Court, and the demolition was stayed on 9 January by the state government of Delhi. The case is currently pending in court.

These short-notice or without-notice demolitions have traumatised those made homeless. In Tughlakabad, some have moved out, but those who remain live amidst mounds of rubble, clearing it by hand in a desperate attempt to build temporary shelter.

Some live under umbrellas, some in auto rickshaws, many out in the open.

On the morning of 6 May, MCD officials arrived once again, accompanied by police to remove the tarp-and-plastic shelters many had constructed over rubble. Residents tried to stop them. About half were removed.

“Our politicians have deceived us,” said Singh. “They used us for votes, but now when we need them, they have turned their backs on us. Nobody has even paid us a visit, nor offered us a drop of water—forget providing us the rehabilitation we are entitled to. Atishi [of the Aam Aadmi Party] has even stopped picking up our calls.”

We sought comment from Kalkaji member of legislative assembly (MLA) Atishi—who uses only one name—over email, phone and text message but there was response. We will update this story if she responds

[[https://tribe.article-14.com/uploads/2023/05-May/06-Sat/IMG_5745.jpeg]]

Evictions Without Rehabilitation

Since 1988, the boundary between the Mehrauli Archeological Park (MAP)—where G20 delegates are scheduled to go on a heritage walk—and Mehrauli village in south Delhi has been a point of contention between the DDA and local residents.

The DDA claims that the boundary land falling in MAP has been illegally encroached by slum dwellers and builders and the encroachments are being removed. But the authority has yet to prove to the court that it owns the land from which it is evicting people.

Before the demolition, Isra and her joint family of twelve lived in a cramped pucca or concrete house in Mehrauli, within a cluster of jhuggis, many of which were demolished. She lived in this home for more than four decades. Before Isra’s family constructed their pucca home, it was just a mud-and-thatch hut.

With nowhere else to go, her family now lives amidst the rubble.

[[https://tribe.article-14.com/uploads/2023/05-May/06-Sat/IMG_5558.jpeg]]

The demolitions near Tughlakabad fort followed a Delhi High Court order in February 2023 to the ASI to remove unauthorised constructions from public land, and to rehabilitate those whose homes were demolished.

No rehabilitation plan was provided to any of the affected families.

In 2010, the Delhi High Court held that denial of rehabilitation amounted to a “gross violation” of the fundamental right to shelter. Evictions should follow UN guidelines, which require authorities to show that an eviction is unavoidable, said the court, and should not make people homeless.

Aside from court orders, the Delhi Slum and Jhuggi Jhopdi Rehabilitation Policy of 2015 also forbids the government from demolishing any slum built before 2006. Gosiya colony features on such a list of such slums.

The ban on demolition, however, does not apply in certain exceptional cases, if a slum falls within a park, for instance.

In the case of Mehrauli, if the land falls within the archeological park, as the government claims, the policy’s clause 2(v) requires the Delhi Urban Shelter Improvement Board to “make all efforts” to relocate jhuggis in a slum.

“Do we not belong here?” asks Roshi Mehnaz, a 43-year-old homemaker, resident of Gosiya colony, a neighbourhood of 400 jhuggis. She has lived there for 33 years since 1990. In 2013, her home was demolished, and her family rebuilt it.

“Politicians have homes so big that they could house dozens of families,” she said, weeping as she recounted the demolition. “But the people who elect them to power, should they not have any home at all?”

Uprooted Again

Mehrauli, one of the country’s oldest inhabited urban settlements, is classified administratively as an “urban village”. It hosts a diverse population, some living in slums and others in apartment buildings overlooking the archeological park.

Many claim they have been here since after Partition, but their location near the park has now made them a target.

[[https://tribe.article-14.com/uploads/2023/05-May/06-Sat/IMG_5491.jpeg]]

“Encroachments don’t take place in the dead of the night—one cannot build an apartment in a place like Mehrauli without the connivance of the state in some way,” said Gautam Bhan, associate dean, School of Development at the Indian Institute of Human Settlements. “So, this becomes a question of selective application of law, which is arbitrary at best and discriminatory at worst.”

A year after a court-ordered survey, as the G20 preparations kicked in, lieutenant governor Saxena ordered the DDA to remove encroachments around the MAP, and, so, the demolitions began.

Arguing the demolitions were an “illegal act”, a number of affected property owners who live in the apartments bordering the park have filed petitions before the high court.

They claim that the land was allotted to them by the Union government under the Displaced Persons (Compensation and Rehabilitation) Act, 1954. After India’s partition in 1947, similar compensatory properties were allotted across Delhi to those who migrated from Pakistan.

“There are a number of people who have documents showing that their land is under their ownership, and whose land is certified as residential land,” said advocate Kawalpreet Kaur of the Delhi-based Human Rights Law Network, which is providing legal support to Gosiya residents.

[[https://tribe.article-14.com/uploads/2023/05-May/07-Sun/IMG_9920%281%29.jpeg]]

Despite claiming for years that the border of the MAP was being encroached, the DDA never made attempts to stop construction there—until the G20 summit came closer.

The DDA officials we contacted—the DDA commissioner, senior law officers, deputy director, and public relations director—declined comment.

As the Delhi High Court hears pleas of owners who were served demolition notices, the Delhi government of the AAP has called on officials to carry out a fresh survey of the park.

For Isra and hundreds of those who have lost homes across Delhi, that will make no difference.

Get exclusive access to new databases, expert analyses, weekly newsletters, book excerpts and new ideas on democracy, law and society in India. Subscribe to Article 14.

(Prudhviraj Rupavath is a land and forest governance researcher and Mukta Joshi a lawyer with Land Conflict Watch, an independent network of researchers studying land conflicts, climate change and natural resource governance in India.)

Editor's note: The writers have made clarificatory edits wherever the figure 2,50,000 is mentioned in order to emphasize the source of the data, which is based on media reports and not the writers' own calculations.