Mumbai: Delving into the history of India’s pre-independence census exercises in his new book The Caste Con Census, civil rights activist, scholar and author Anand Teltumbde writes that colonial administrators, alarmed by the revolt of 1857 and the possibility of subsequent pan-Indian resistance, formalised their divide and rule policy.

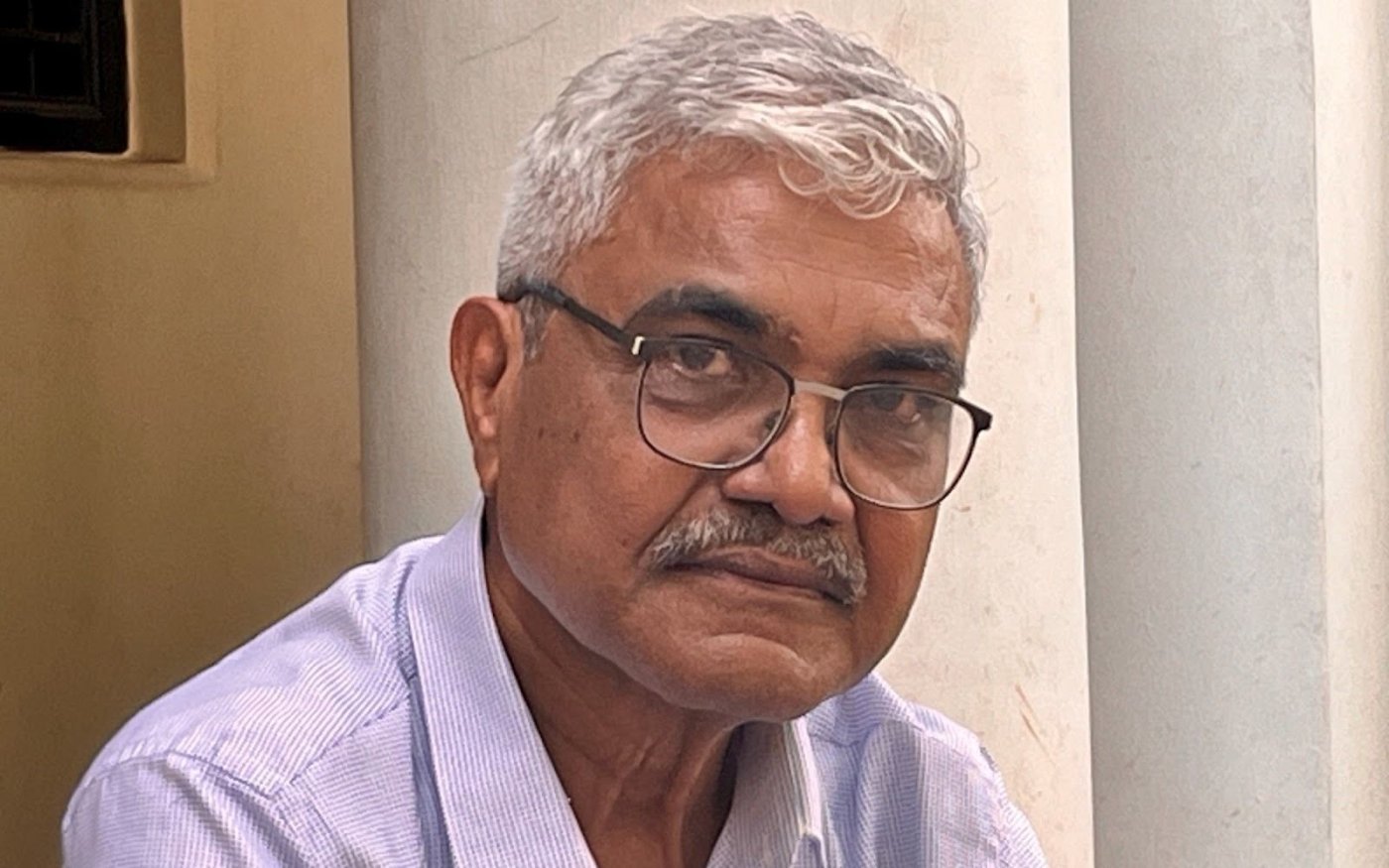

“Its response was twofold: to foster and institutionalise divisions among people on the basis of caste, religion, tribe and community; and to produce exhaustive knowledge about society through enumeration, classification and codification,” writes Teltumbde, 75, a former professor of management at the Goa Institute of Management. The decennial census, launched in 1871 and systematised in 1881, fortified caste, transforming fluid social affiliations into rigid and state-recognised categories, allowing for a “segmental control of society”.

Such a caste enumeration, excluded from census operations conducted since independence but demanded by various groups periodically, returned to centrestage in 2010, when the Manmohan Singh government formed a group of ministers to deliberate on the subject. The government eventually opted for a survey, in 2011, the socio-economic and caste census (SECC), conducted by the department of rural development, the ministry of housing and urban poverty alleviation and the ministry of home affairs.

While the SECC’s socio-economic data was made public in July 2015, its caste component, however, was shelved by the NDA government.

In a September 2021 affidavit to the Supreme Court, the government said the SECC’s caste data was “unusable”, “replete with technical flaws”, and that a caste census was “administratively difficult and cumbersome”. This was in response to a plea by the Maharashtra government seeking the SECC’s caste data in order to implement a 27% reservation for other backward classes (OBCs).

Having effectively ruled out a caste census in 2021, on 30 April 2025, the cabinet committee on political affairs chaired by prime minister Narendra Modi decided to include caste enumeration in the upcoming census, declaring this to be a demonstration of the government’s commitment to the “holistic interests and values of the nation and society”.

Some states’ surveys to enumerate castes had been conducted “purely from a political angle, creating doubts in society”, the government said.

Published by Navayana, The Caste Con Census argues that castes are countless, for caste as an entity tends to divide and subdivide, and questions the widely held belief that such an enumeration will help redress inequalities.

In an interview with Article 14, Teltumbde linked the Modi government’s sudden turnaround to electoral calculations—the 2024 Lok Sabha result leaving the BJP short of a clear majority, with evidence of the upper layer of OBCs, the party’s core voter base, being disenchanted with it, prompting the party to lure the lower strata.

Released on bail in November 2022 in the Bhima Koregaon case after spending 31 months in Navi Mumbai’s Taloja central jail, Teltumbde also reflected on incarceration, unfreedom and the role of public intellectuals in times of state repression. The first accused in the case to be granted bail on merits, the Bombay high court said evidence against him did not in any manner suggest that he had committed a terrorist act.

Excerpts from the interview:

Decades of reservations have not made a dent in the lived reality of India’s scheduled castes (SCs), who continue to experience extreme inequality in education, employment, income, health, etc. Does affirmative action in India need to be reformed? Does the Supreme Court order permitting sub-categorisation among SCs provide a solution?

There is a difference between affirmative action, the American system, and reservations. Ours is a fixed quota granted for certain communities, so quota system is a better term for our reservations.

At this juncture, after 70 years of implementation of this reservation system, talking of reforms would probably be just an academic exercise, because a lot of damage has already been done. Hardly anything remains of reservation today because over the last three decades of neoliberal devastations. The domain for application of reservation stands substantially eroded. Like any other problem in this country, like Kashmir or the Maoist problem, the reservation issue also needs to survive to sustain political tonality.

Anyway, what is the objective of reservation? That fundamental question is never asked. The demand for sub-categorisation of castes entitled to quotas dates back to the mid-1990s, originating with the Mala-Madiga conflict in Andhra Pradesh. The Madigas accused the Malas—numerically dominant among the Scheduled Castes (SCs)—of cornering a disproportionate share of reservation benefits. The charge was that the most populous caste among the SCs had monopolised the advantages of quotas, leaving smaller castes high and dry.

How do you measure such a claim? Naturally, a more populous caste will have greater representation and visibility. For historical reasons, they had an initial advantage too.

Whether they have indeed grabbed a greater share of reservation is a statistical problem. It can be examined using tools like the Gini Coefficient to assess intra-community inequality in the distribution of reservation gains

My hypothesis, given the absence of reliable data, is that inequality within a caste cluster might not differ much from inequality across castes. Still, the political appeal of the argument—that the Madigas have been left out vis-à-vis the Malas—is obvious.

In fact, such disparities were intrinsic to the reservation policy itself. Once you open the door to sub-categorisation, you invite further complications.

Each state’s SC list includes 60 to 80 castes. As any Class 12 statistics student knows, averages conceal more than they reveal. A pit may be 30 inches deep on average, but one end could plunge 3 metres, deep enough for someone to die. Sub-categorisation attempts to group castes based on these deceptive averages. It’s a superficial exercise—actually, an idiotic one.

Earlier, the Supreme Court had rightly rejected this demand, but in January this year, it endorsed sub-categorisation. No explanation is needed for Supreme Court verdicts these days. This one defies constitutional logic as many others.

Does sub-categorisation solve the problem? My answer is no with a capital N. The idea rests on the false premise that castes can be neatly grouped. If there are 83 castes listed, you can't have 83 groups. Moreover, each caste is itself internally segmented into sub-castes and sub-sub-castes, sometimes numbering in the dozens. Caste is a notion, not a physical object. It keeps splitting like an amoeba, with the notion of hierarchy. That is precisely why I’ve long argued that caste can never serve as a category for radical transformation.

Every sub-category you create will reproduce inequality within itself, spawning new grievances tomorrow. Each group will in turn allege that some other sub-caste has grabbed all the benefits. The result is an endless loop—the very problem you claim to solve will be perpetuated ad infinitum.

So what reform to the reservation system do you recommend?

It’s not rocket science, and one wonders why this never occurs to our scholars and intellectuals.

The benefits of reservation accrue to individuals—at most to their nuclear families, not even to their siblings. The policy designates a collective domain called ‘scheduled castes’, within which individuals are treated as potential beneficiaries. Once a beneficiary receives the benefit, the system should automatically reduce their chances of further benefits in proportion to what they’ve already gained. That's all it takes.

With today’s computerised systems this could be implemented effortlessly. Even in the 1950s and 1960s, it wasn’t technically unfeasible—it was perfectly doable. The fact that it wasn’t done was no accident; it was a deliberate mischief. The ruling elites never wanted caste to disappear.

When India gained independence, power merely passed from one set of rulers to another—from the British to the native elites. What really changed? They shrewdly retained the same state apparatus, the same administrative processes, even the same personnel. They framed a new Constitution that in essence, continued the colonial one. They proclaimed India a republic, a welfare state, a pro-people democracy—but beneath the rhetoric, nothing of substance changed.

Do current anti-caste movements offer any hope, whether directly in politics or in academia, to break free from systems where caste remains perpetuated?

Unfortunately, there has not been a truly anti-caste movement since Ambedkar. Babasaheb gave a profound slogan—annihilation of caste. He might have been the first person to articulate the issue with such clarity. Marx, long before him, had described caste as the greatest impediment to India’s development, implying, in effect, that India could not progress unless caste was destroyed.

Caste, however, doesn't arise from any religious scripture or a written command. Social systems evolve from material realities, and those in power later codify and sanctify them. At best, one can understand it as a dialectical process.

Ambedkar’s struggle for representation began with political representation. During colonial rule, when reservations were first introduced, the colonial rulers actually took cognizance of the exceptionality of the untouchables. These were people unlike any other community in the world—subjected to extreme degradation unique to India’s caste order. That is why the colonial government conceded reservations only for the untouchables and created a virtually closed schedule of the identified people on the incontrovertible criterion of untouchability, after an intensive survey across India.

In post-colonial times, that fundamental exceptionality was diluted.

Reservations were expanded to include various other backward communities and the language of policy itself shifted. This proliferation was political. Reservation was never the only means to uplift disadvantaged communities, treating it as such reflects sheer political bankruptcy.

Thus reservations were extended to scheduled tribes (ST). Now by no means am I castigating this. I am not suggesting that Adivasis who were called ST did not deserve it. Rather like the SCs, the STs were also segregated from mainstream society. They were forest dwellers, away from so-called civilisation. Though morally justified, the problem with extending reservations for them was that unlike the SCs, they lacked the definitive criterion of untouchability. The forest could extend to Ranchi, it could extend to urban areas, to Nagpur. Predictably, you will find that the benefits of reservation for STs are monopolised by such urban communities in every state.

With all these pitfalls, there was an option of including the STs and instituting the mechanism of ensuring that a beneficiary’s chances are dampened in proportion to benefits already received. It would have destigmatised the schedule of SCs being associated with untouchability, because the adivasis or tribals did not have a caste.

The proliferation continued with the inclusion of ‘backward castes’ in the Constitution. But what was this backwardness? Unable to define it, the state concocted a vague criteria of social and educational backwardness. No one ever questioned the absurdity of this.

In the 1940s and 1950s, India as a whole was educationally backward and in this hierarchised society, no community theoretically could be excluded as not socially backward. How could such a criterion meaningfully distinguish who qualified for special policy measures? Yet this flimsy basis was enshrined in a critical constitutional provision.

The consequences were predictable. Every caste could legitimately claim that it is “socially and educationally backward.”. Empirically we have seen that there is hardly a caste left that has not demanded reservation. Thus the very premise of the policy became self-contradictory. Instead of addressing inequality, it deepened caste consciousness and competition. It actually aggravated the problem.

The Congress reluctantly instituted the Kalelkar Commission to identify the socially and educationally backward groups in 1953, but then it rejected the report. Decades later, the Janata Party instituted the Mandal Commission for the same purpose, but the government collapsed before its report could be implemented.

Years afterward, the politically beleaguered V P Singh government suddenly adopted the report, triggering a political earthquake. Years later, I happened to meet V P Singh in a hospital in London, and I asked him, “Tell me the truth, was it not your political ploy?” He just smiled.

In the book, you argue against the caste census, but proponents would say that data is valuable, that any kind of policy to be created going forward would require empirical data on castes. What do you say to them?

This connects back to my first point-- that reservation as a matter of right has lost its salience.

Are we talking about a caste census and linking it to the annihilation of caste? Oh, that’s light years away; it can never be linked with the annihilation of caste. The caste census along with the demand for reservation from the Marathas, Rajputs, Jats, Gujjars and other dominant rural castes, are twin reactions to the neoliberal order ushered in after 1991.

Neoliberalism dismantled public goods, hollowed out the welfare state, and created a pervasive crisis. Modi’s EWS reservation, too, must be seen in that light—it was a way to placate the frustration of the dominant groups while advancing the BJP’s ideological and political agenda.

I called it a twin reaction. From the lower castes came the demand for a caste enumeration—based on the belief that enumerating caste would help defend redistributive politics from being erased by neoliberalism. From the dominant castes, it is about reclaiming their losses due to neoliberalism—withdrawal of subsidies, increased input costs, volatility of agricultural prices, and no jobs for their educated children, creating a feeling of decline in their social prestige—in a different idiom of grievance: we too are backward, so we too deserve reservations.

For years, while Opposition parties demanded a caste census, the BJP opposed it. In 2021, the government filed an affidavit before the Supreme Court explicitly stating that caste enumeration would not be undertaken as a matter of policy—and that the Court had no authority to intervene. In the 2024 election campaign, Modi even dismissed the caste census demands as an “urban Naxal” idea.

Then on 30 April this year came the volte face: the union cabinet decided that the next census would include a caste enumeration. With that move, Modi punctured the opposition’s single-point agenda. And because the Opposition is politically bankrupt, having put all their eggs in one basket, it was left without an issue.

Why is Modi doing this now? Modi does nothing that isn’t tied to electoral calculation. The 2024 Lok Sabha result and the importance of Nitish Kumar's 12 MPs, and Chandrababu Naidu’s 16 MPs explain part of the story. Bihar is headed for elections, and Nitish Kumar had already conducted a caste survey there. That exercise, however, produced little. Policy steps based on it have been stalled by the Supreme Court.

Electoral clues tell the rest. The 2024 results showed that the upper OBCs, the BJP’s crucial base, have drifted away. Their support eroded significantly, accounting for the BJP’s losses. This upper OBC stratum is relatively educated and capable of seeing through the BJP’s tactics. Hence, the lower strata are now being lured with the promise of a caste census and targeted resource benefits. This is the constituency the BJP seeks to consolidate.

The real puzzle is the intellectuals and scholars who uncritically champion caste enumeration. Much of today’s scholarship has turned populist—it merely follows the prevailing sentiment. If the lower strata, in their imagination, are clamouring for caste data, these scholars dare not stand apart. Even some otherwise serious academics have fallen into this trap.

What is a caste enumeration, and what do its supporters claim? That it will “show the real picture” of society with data. Professor Satish Deshpande, for instance, called it a “selfie”. But what do you do with that selfie? As our selfies at the most circulate on social media to get momentary likes, this selfie too may meet the same fate. On its own, it will not create a policy, for it is just a diagnostic snapshot on the condition of various communities in the country.

And what would such data reveal? Likely three things: First, that backwardness cuts across caste boundaries; second, that caste based quotas haven't dramatically altered inequality; and third, that the government could use this to argue for a shift from caste to economic criteria—something the RSS has wanted from the beginning. In all likelihood, the BJP will use the data to construct the narrative for accomplishing abolition of caste based reservation.

Among the Opposition, Rahul Gandhi has been the loudest advocate, echoing Kanshi Ram's slogan—Jiski jitni sankhya bhaari, uski utni bhaagidari. (A proportional share based on numbers.) But, what does he mean by bhaagidari? Representation in Parliament? Share in government jobs?

Let’s look at the numbers. India’s labour force today is around 500 million. Only 6% of it is in the organised sector, 94% is unorganised. Of this, at its peak, 68% was in the government and PSU sector. And among these, 15% is reserved for the SCs. When you compute the actual beneficiaries of reservation, barely 0.0003% of SCs—three in a thousand—benefit or can potentially benefit. No one presents this reality.

In the wake of discussions around reservations in the private sector, I myself did a rough study in some Pune industries and found that nearly 35% of working class jobs were held by SCs—without reservation. It was no surprise; Dalits are a working class and they would naturally preponderate among workers. These jobs are akin to C and D class jobs in the government and PSU sectors. Considering the pyramidal structure of the government-PSUs, one can safely hypothesise that even without reservation, the SCs could have due representation in C and D class jobs, and reservation therefore mattered in only class B and A jobs. If so, the significance of reservation reduces further to a minuscule level.

The uproar over reservations and caste enumeration, then, serves more to humiliate Dalits than to uplift them.

After Ambedkar’s death, the political establishment reduced the entire anti-caste project to the politics of reservation. The post-Ambedkar movement, too, became trapped in that narrow frame. More data from caste enumeration will not change this—only reproduce it.

You read more than 170 books over 31 months in prison, worked on four new books, and there are some more in the works. Could you describe this rigour and discipline in your reading and writing while in prison?

I began publishing under my own name in the 1990s. Before that, I wrote under various pseudonyms. So, in a sense, my formal writing career began alongside the dawn of neoliberalism in India. By then, I was already in senior management, travelling constantly, attending meetings, and juggling responsibilities. I continued writing and publishing through my corporate life, even as CEO.

Over time, I emerged as a major critic of the government policies. Someone once wrote in the New York Times that I was the fiercest critic of Modi, but of the government before him as well.

I mention this background because, back then, time was always scarce. I wrote mainly to feed the activists’ circle with analyses, and they remain the readership even today. They often translate my work into regional languages and take it to the grassroots—or at least, that is my hope.

In jail, after the initial shock, I realised within a week that books are allowed—not by default, but thanks to the consistent fights the Bhima Koregaon accused had waged with the prison administration. Initially, they would allow only one or two books, but eventually any number were permitted.

As I wrote in my prison memoirs also, reading and writing became a survival strategy. Without them, I would not have survived. Initially, I read any kind of book that came my way. I just kept count—just for fun—which later came handy to see the count of 179. I read lots of Marathi books, which I rarely read before.

There was a small library in the jail, with four almirahs full of books, two Hindi, one Marathi and one for English and Urdu titles. I exhausted all their readable books over the next three to four months during the pandemic when they were not delivering even newspapers.

Slowly, I started keeping notes, without any intention. This was during the pandemic. The only means of guessing what was happening outside was a TV set kept in a corner. Eventually, 22 notes out of 100-odd such notes became a jail memoir.

People are stunned at the number of books I managed to read—I’ve always been a fast reader. In jail it earned me a nickname, the Rajnikant of Books—because inmates thought I finished books just by flipping through them.

Many of the young men in jail, especially the Muslim bomb blast accused, were well educated and also received books. Some would reach these to me through the guards, and once I finished, it would find its way back to its owner. This informal network kept a steady flow of reading material going.

Writing, however, had its constraints. I’ve always been a late-night writer, but in jail, we were supposed to be sleeping by 10 pm. The other thing was that the tubelight hung from a ceiling that was perhaps 20-25 feet high, so it emitted a dim light that strained the eyes. I got a corridor light fixed so that the combined light would ease the strain and I would stretch my writing to a couple of hours beyond the prescribed time.

The jail canteen provided plenty of writing material, and I made full use of it. Although I was permitted a plastic chair, there was no writing desk. But some inmates gifted me a thick cardboard pad to place my sheets on and write. I wrote drafts of four books. After my release on bail, I used only some notes to publish my memoir; the other three drafts remain untouched.

The Caste Con Census was written over the past two months. My previous release, Iconoclast, was actually completed as a manuscript before I went to jail, but I rewrote it after my release.

What are the three remaining draft manuscripts about?

One book was a letter to Babasaheb Ambedkar—a deeply personal letter that traversed the entire gamut of his policies, thoughts and actions that had come to shape the framework for most Dalits. A second one was on nationalism, and its discontent. I might take that up next. The third is on the making of the Constitution, tentatively titled We, The Non-People of India.

And what were you reading in those days that you remember?

I read so many books, many useful ones. It is difficult to name a few but I could name some that resonated with me then.

I relished Christopher Jaffrelot’s Modi’s India, which comprehensively presented the picture of India after 2014. Then I came across In The Name Of The Volk: Political Justice in Hitler's Germany, by H W Koch. It was a fascinating account of how the courts became puppets of Hitler's regime, providing parallels to what started happening in Indian courts.

A third memorable book I read was Shoshana Zuboff's The Age Of Surveillance Capitalism, about big data companies like Google, Meta, Amazon, Microsoft, etc that have created an economic order based on extracting, commodifying and monetising the personal data of people. These three books stand out, though I read many other important books of history ranging from Genghis Khan to Palestine.

How did incarceration either shape or impact or in any way alter your view of what it means to be truly free?

I've been a civil rights activist since the birth of the movement post-Emergency. So I wasn’t innocent about what freedom and unfreedom mean.

Before my incarceration, however, I used to think of freedom in structural terms, embedded in caste, class, stigma, the perceived architecture of the State. Incarceration actually transformed it. Jail is an abstraction until it happens to you; and the abstraction is transformed into a lived experience.

We started viewing things differently because external liberties were stripped away from us, our movement was restricted; even if we were dying, they would not take us out to a hospital. So you discover the different domains of freedom. I found that an inner space existed that could not be occupied by the powers that be. That space provided the motive force for me to fight against the excesses of jail administration as well as to write for the posterity. Many reforms came to jail that benefited everybody because of the struggle put up by us, the Bhima Koregaon accused.

This discovery—that there exists a space which cannot be captured, a space of critical consciousness—was vital. Outside jail, we tend to define freedom as the absence of restraints. But perhaps what matters more is that inner space—the preservation of one’s critical consciousness. Under the kind of regime that we live in today, thinking freely itself has become perilous. It comes at a steep cost—social isolation, vilification, imprisonment. Our case stands as proof that it can happen to anybody. They can pick up any person without reason, and keep them imprisoned for years.

Six of our co-accused are still in jail; two people are in their eighth year of incarceration, in an absolutely fabricated case. This can happen to anyone—they can ruin your life. Even after bail, we are not truly free. There are serious restrictions on our movements. Varavara Rao and Sudha Bharadwaj, for instance, were not allowed to leave Mumbai after securing bail. It is an unbearably expensive city to live in. At the age of eighty-four, Varavara Rao, living with his wife in a small flat, had to plead before the court to return to Hyderabad, a plea that was rejected.

How did Stan Swamy’s death affect you in jail?

Stan Swamy was one of the last three in our case to come to jail. Stan was quite a healthy person but for his apparent Parkinson's and his deafness. We were more worried about Varavara Rao. Had he not been taken to Nanavati hospital in time for treatment, worse would have happened.

Stan’s passing was unexpected. The jail hospital did not have proper doctors, nurses, compounders or orderlies but the jail administration kept claiming that they had a fully equipped hospital.

During the pandemic, they were not even conducting simple tests. People died but were probably assigned various reasons other than Covid-19. Nobody dies as such of Covid-19.

The biggest risk that we faced was the jail administration’s reluctance to take us to an outside hospital. I myself suffered it when struck by the Covid-19 virus. It was sheer luck that I survived after a brush with death over five days.

Only in the wake of alarming conditions created by the second wave of Covid-19 did the jail administration begin tests, on 25 people, that included Stan and I. Vaccination came later, and Stan and I were vaccinated together, at the same time.

Stan was a saintly figure, always talked about the sufferings of people. I would walk in the corridor with him every morning. He was childlike. The deterioration of his condition was noticed when there was a change in his behaviour. It was confirmed by his oximeter reading that dipped below 80. We pleaded with the doctors and jailors but in vain. They acted only after five days when the court ordered him to be moved to Holy Family Hospital. The delay proved fatal.

Stan had been the source of motivation for many. His passing sent a shock wave among us and outside. Any one of us could die his death, and the jail administration would keep claiming that it provided all due treatment.

How is state repression affecting India’s intellectual tradition? Does repression silence movements or radicalise some of them? And in such times, what should be the role of the public intellectual?

It’s a fact that state repression silences people—and our case was meant precisely to terrorise people into silence. The term ‘urban naxal’ now potentially includes just about anyone who dissents. Many have indeed been silenced. Fear seeps in quietly; after we got bail, people who once freely spoke to us or wrote to us now avoid contact. Fear has many forms, and it is deeply internalised.

At the same time, repression also sharpens awareness—it exposes the stakes and radicalises some, who link critical thought with action and continue to struggle. Such resistance may not always be visible, but it persists. State repression cannot silence an entire people.

As for the role of the public intellectual, that is a difficult question. A public intellectual—anywhere, at any time—must have the moral spine to stand firm, even if the entire world turns against him. Sometimes, death itself becomes the message that one was right. Even in the natural sciences, thinkers like Galileo had to defend truth against the combined might of the church and state. That kind of courage—the moral clarity of the true public intellectual—is largely missing today.

A public intellectual is not a title; it’s a self-internalised role. If people listen to you, it’s because you articulate something on their behalf. I’ve internalised that role, and I’ve paid a price for it—a price I’m prepared to keep paying.

It comes back to that inner space of freedom, that critical consciousness, which no power can occupy unless the individual himself surrenders it.

(Kavitha Iyer is a senior editor with Article 14 and the author of ‘Landscapes of Loss’, a book on India’s farm crisis.)

Get exclusive access to new databases, expert analyses, weekly newsletters, book excerpts and new ideas on democracy, law and society in India. Subscribe to Article 14.