Srinagar: High-speed Internet is a threat to national security. It can disrupt elections. Radicalize the youth. Spread videos on social media. Act as a tool to frighten people from casting their votes. Help terrorists infiltrate India’s borders.

As a 550-day ban on 4G mobile Internet services ended in Jammu & Kashmir (J&K) on 5 February 2021, we look back at the many changing and seemingly illogical reasons that were used to curb its use.

From January 2020, the home department of J&K’s union territory government issued more than 140 orders to either extend the ban on high speed Internet or even suspend the more basic, slower 2G connection. The latest order, issued on 22 January 2021, extended the ban until 6 February.

When the home ministry ordered a suspension of Internet services to “maintain public safety” and “avert a public emergency” at Delhi’s borders, where farmers have been protesting to demand the repeal of two contentious laws, citizens in the border states got a tiny taste of J&K’s prolonged internet woes.

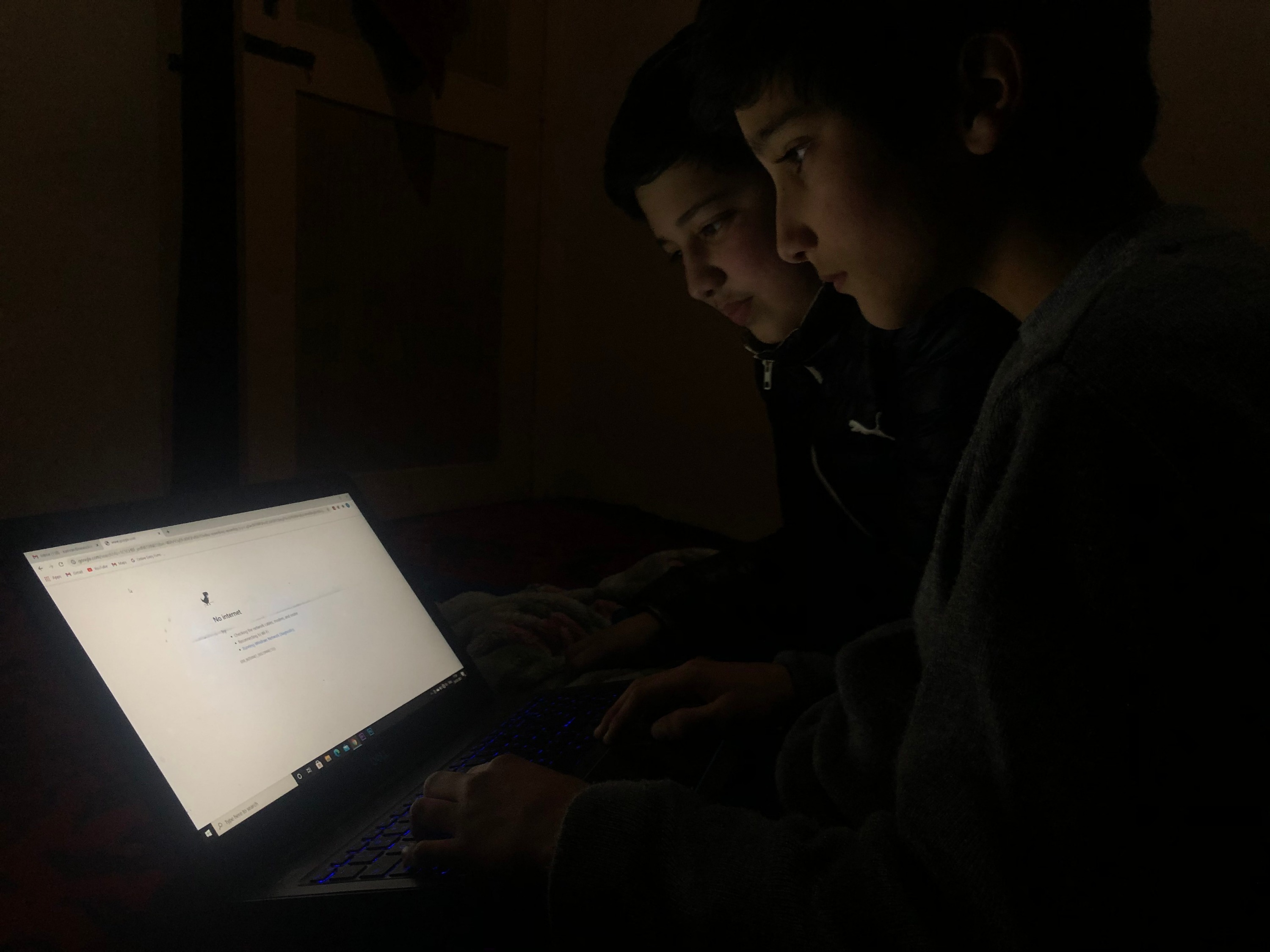

J&K’s ban, one of the world's longest, came at a time when due to the Covid-19 pandemic, classes were being conducted online, and work from home was a necessity. Across India, there was a shift to online shopping and entertainment to ensure safe-distancing practices, except J&K.

“Sometimes the Internet is snapped during classes because an encounter has taken place and sometimes the slow speed of the Internet makes the teacher’s voice inaudible,” Insha Bhat, a 10th standard student told Article 14. “The ban on the 4G Internet has made students suffer.”

An August 2020 report titled Kashmir’s Internet Siege by the Jammu and Kashmir Coalition of Civil Society (JKCCS), found that 12.5 million people in the region could “barely video call their friends or family, attend online classes, webinars or conferences, use apps to have their groceries or medicines delivered, entertain themselves by streaming a film, or download the latest World Health Organization (WHO) recommendations and health guidelines”.

Mobile Internet bandwidth is “officially throttled to 2G—a speed which does not allow full functionality for most websites and web based applications,” the report said.

According to consumer website Comparitech, from 2020 to 2021, Internet blackouts and social media restrictions cost the world’s economy more than $4.5 billion in 2020. Of this, $2.5 billion, almost 60%, comes from over 100 shutdowns in India, mainly within J&K.

The current ban on 4G Internet services began after the abrogation of the special status of J&K on 4 August 2019. Internet services were shut for 215 days until 4 March 2020 in the former state, according to the Software Freedom Law Centre (SFLC), an advocacy that monitors Internet shutdowns in India.

Landlines and mobile services were affected by the communication blockade. Although the ban on landlines was lifted, mobile Internet continued until 5 February 2021. On 25 January 2020, 2G services were restored only to verified users in the Valley.

The government has been issuing multiple orders to justify the suspension of the 4G Internet service in J&K.

Internet freedom around the world has been on the decline for three years, according to Freedom House, a democracy rights watchdog. Even excluding J&K, India had the most Internet shutdowns, from 1 June 2019 to 31 May 2020, in response to nationwide protests against the Citizenship Amendment Act, 2019 (CAA), and attempts to control the online narrative around the Covid-19 pandemic.

The International Press Institute in March last year asked India to lift restrictions on the Internet, so that journalists could get back to work.

On 11 May 2020, the Supreme Court ordered the setting up of a special committee to consider pleas for the restoration of 4G in J&K. On 16 July, the Centre and the J&K administration told the court that a special committee has been constituted to examine the ban. And in August 2020 the government restored 4G on a trial basis in the northern districts of Ganderbal and Udhampur.

We examined some of the key reasons offered by the government through 2020 to ban 4G services in the rest of J&K.

Date: 3 April 2020

Reason: The New Domicile Law

Order: The ruling Bharatiya Janata Party feared its controversial new domicile law, introduced in March, might trigger protests.

The home ministry’s order claimed that in the past, many instances of the misuse of data had been noticed: “The recent changes in the domicile law too has the potential to be exploited by those inimical to public peace and tranquillity and cause large-scale violence and disturb public order, which has till now been maintained due to various pre-emptive measures, including restrictions on access to Internet with relaxation in a calibrated and gradual manner, after due consideration of the ground situation.”

Date: 27 May 2020

Reason: The Onset Of Summer & Melting Snow

Order: The threat of attacks by “terrorists” features in almost all the orders issued to prolong the ban on 4G Internet.

An example of how the government thinks that 4G is “anti-national” and harmful for the peace of J&K can be gauged from this order: “There have been multiple instances of terrorist acts including attacks on security forces–leading to even death of the SF (special forces) personnel, and attempt to encourage terrorism through uploading and circulating of provocative videos and false propaganda–largely relying on Internet connectivity, to disturb the public order.”

The order said that “reports suggest rise in infiltration of terrorists during the coming weeks due to the onset of summer and melting of snow, which gets facilitated through use of Voice on Internet Protocol and encrypted mobile communication, being used by the operatives/ anti-national elements to communicate with their handlers from across the border.”

The Internet speed restrictions have not posed “any hindrance to Covid-19 control measures including the use of mobile apps, assessing online educational content or carrying out business activities, but has effectively checked the unfettered misuse of social media for incitement and for propagation and coordination of terror activities,” it stated.

Date: 12 November 2020

Reason: Terrorist Interest In Elections

Order: Ahead of the 28 November District Development Council (DDC) elections across the newly-formed UT—the first such political exercise since the abrogation of Article 370—the government said a “the high level of interest” in the elections made it likely that “terrorist and separatist elements shall make every possible attempt to disrupt the democratic process”.

The order added that in the recent past, “there have also been targeted killing of the civilians/political activists” by terrorists to dissuade the general public from participating in the election process.

Date: 26 November 2020

Reason: Campaigning For Elections

Order: Weeks after saying that 4G Internet can play spoilsport in conducting DDC elections, the government issued another order stating that the elections had resulted in “intense political activity” with “extensive campaigning” by candidates.

“At the same time, there have been continued attempts from across the border to disrupt the elections process by vitiating the security environment,” the order warned.

Law enforcement agencies, the order added, “have well founded apprehensions of enhanced efforts by Pakistan for causing public disaffection, recruitment in the terrorist ranks as well as infiltration attempts, which heavily depend upon high speed Internet.” It cited a “surge in terrorist activities”, listing two incidents.

The order said that “taking note of misuse of social media applications in carrying out terror activities as also in adversely impacting public order” it was clear that the restriction should continue.

Date: 11 December 2020

Reason: 4G Can Be ‘Misused’

Order: “Due to the likelihood of the misuse of data services by anti-national elements to disrupt the democratic process by creating a scare among the voters, carrying out attacks on security forces, targeting of contesting candidates and workers,” the order said.

It cited “abundant caution” as a reason for restricting the Internet on polling days and added that “there are attempts to radicalize youth through multiple methods, most importantly, through “videos using social media, which rely on high speed Internet for easy dissemination of such material.”

The ban on 4G was extended till 25 December.

Date: 25 December 2020

Reason: High Voter Turnout

Order: The government argued that the successful conduct of the recently concluded panchayat elections including “large scale voter turnout”, “has not gone down well with the elements inimical to public peace and tranquillity, as apparent from the multiple incidents of hurling of grenades by the terrorists since the conclusion of the election process, targeting the civilian/ police personnel/ security forces and the encounter within the security forces.”

The government, in its order, further said that it had information that many terrorists were trying to infiltrate the border and “it was the curbs on high-speed Internet that had blocked their attempt to do so.”

The government said it would restrict high-speed Internet until 8 January 2021, then extended the ban until 6 February.

When Even 2G Is Suspended

After suspending the Internet for over five months, the government in January 2020 restored 2G Internet in Kashmir. But every time there was an encounter or elections were around the corner, even 2G is snapped.

On 8 December 2020 the government issued an order to suspend the Internet in five districts of south Kashmir, Awantipora, Shopian, Kulgam, Anantnag and Pulwama.

In its order the government stated its fear that some “anti-national elements” might disrupt elections. “The apprehensions for misuse of data services by anti-national elements to disrupt the polling process of the DDC elections, scheduled in the entire South Kashmir Range on 07.12.2020. It is further mentioned that the fallacious material through social media had already started circulating, urging the public not to participate in the ongoing election process.”

In yet another order, the government suspended 2G Internet in Pulwama during an encounter because they feared outrage by the youth. “There was every likelihood of misuse of data services by anti-national elements/OGW’s to communicate with their sympathizers for mobilizing crowds and disturbing the law and order situation, as has been the practice in the past.”

If 4G Is A threat, What About High-Speed Fibre Internet?

The government on the one hand claimed that 4G was a threat, but on the other hand allowed people to install fibre Internet that has a speed starting from 100Mbps to 1Gbps, enough to download files, watch YouTube, browse and download videos.

The public relations officer of Bharat Sanchar Nigam Ltd, Masood Bala told Article 14: “14,000 connections of Bharat Fibre have been provided to people so far in seven months. The demand for the fibre is growing.”

The chief secretary to the government, BR Subrahmanyam, in March 2020 said 4,483 gram panchayats would be connected to high-speed Internet.

With no high speed mobile Internet services in Kashmir, more people opted for wired Internet to study, attend online classes, browse and download files.

“I became a subscriber of Jio fibre in September 2020. The fibre allows you to give your Zoom classes without any buffering. Earlier when I used to give classes, the students would complain of network connectivity,” said Insha Hameed, a school teacher.

Over 3,000 customers subscribed to fibre Internet in Srinagar, according to the Kashmir Monitor in April 2020.

According to telecom subscription data, when Jio started its fibre-to-home service in J&K in September 2019, it had 4,128 subscribers. Within 14 months, in November 2020, the number of subscribers jumped to 57,451.

That growth may now slow, unless mobile services are suspended again.

(Shafaq Shah is an independent journalist based in Srinagar.)