Since 2016, Urzeeba Qayoom Bhat has turned to social media as a tool for activism, a last resort when the government and judiciary failed to deliver justice for the death of her brother after alleged torture in police custody in Jammu and Kashmir (J&K).

The 26-year-old from Srinagar lost her brother in 2010, after he had been allegedly beaten when under arrest in the police station in Soura, a neighbourhood in Srinagar. The first information report (FIR) was registered in the same police station in 2018 against the “State through SHO (Station House Officer) Police Station Soura”, after eight years, under direction from a Srinagar court, while the chargesheet is yet to be filed.

Despite delays and setbacks, Umer’s sister still hopes for justice.

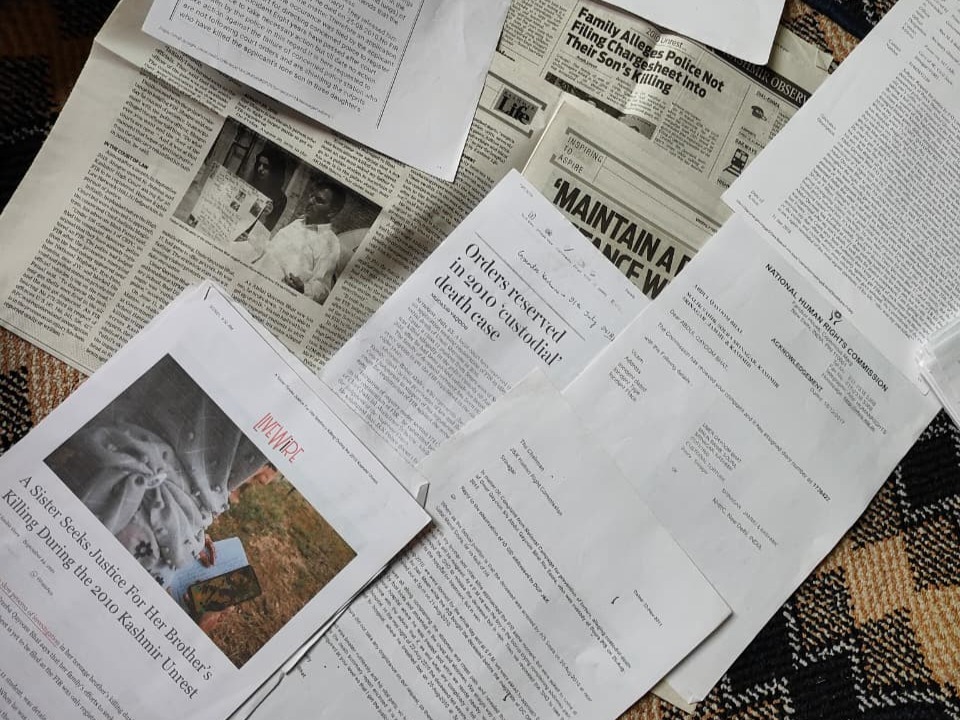

She runs pages on Instagram, LinkedIn and Facebook where she shares photos of Umer, case updates, instances of denied justice, details of legal hearings, and the everyday struggles they face during these proceedings.

On 20 August 2010, 17-year-old Umer Qayoom Bhat was taken into preventive detention when clashes between protestors and security forces broke out across the state after the killing of three Kashmiri youth by the Indian Army in a fake encounter in north Kashmir’s Machil area.

According to the family, Umer was picked up by the police when returning home after prayers. Urzeeba said her father, Abdul Qayoom, rushed to the police station, where he saw him lying on the floor "in a pathetic state". Umer was released on bail the next evening and taken to the hospital, vomiting blood. The family alleged that the delay and the torture cost him his life.

They said the doctor assured them that Umer was fine and discharged him after a casual checkup. On 23 August, Umer was brought back to the hospital where doctors found Umer critical—"90% dead", according to the doctors—and immediately put him on life support. Medical records confirmed “bilateral massive intrapulmonary haemorrhage” (bleeding in both lungs).

He was declared dead on 25 August 2010. The family alleged the death was caused by the beating in police custody and demanded an FIR against the officer on duty.

Over the last 15 years, the family has been fighting for justice, but progress has been slow, and the matter is still pending investigation.

In 2018, the court of the chief judicial magistrate in Srinagar ordered the formation of a special investigation team (SIT) headed by a senior superintendent of police.

The family alleged that the investigation was never conducted.

In 2014, the then state government constituted a one-man commission headed by Justice (retd) Makhan Lal Koul under the Commissions of Inquiry Act, 1952, to probe the deaths of the 120 people killed during the 2010 unrest.

The commission submitted its report to the state government in 2016. The report is yet to be made public. “We are satisfied with the contention of the petitioner that his son died because of Police torture after he was arrested and are of firm opinion that this is custodial death,” the website KashmirLife quoted the Commission as saying in 2017.

In September 2020, advocate Babar Qadri, who was the family’s counsel in the case, was shot dead by suspected militants at his home in Srinagar. “For us, it felt like losing Umer all over again,” Urzeeba said.

After the loss of their lawyer, the COVID-19 pandemic shut down the courts, further delaying matters.

Shafat Mohammad Najar, sub-divisional police officer, Hazratbal, Srinagar, told Article 14 that the investigation into the case is underway.

In the five years from 2016-17 to 2020-21, a total of 33 custodial deaths were registered in Jammu and Kashmir, while there were 687 deaths registered in police custody from April 2018 to March 2023 across the country, according to the Ministry of Home Affairs.

According to the National Human Rights Commission (NHRC) annual reports, from April 2010 to Mar 2024, there were 1996 deaths or rapes in police custody in India. The NHRC does not differentiate between deaths and rapes in police custody in its statistics.

The Makhan Lal Koul Commission had clearly stated Umer’s death was a custodial killing and recommended action. Why do you think there has been no accountability despite these official findings?

Even after such an official finding, nothing has been done. The reason is simple: the very people responsible for delivering justice are the ones implicated in these crimes. Instead of protecting citizens, the government has shielded those policemen who were meant to protect us. Accountability has been deliberately avoided because punishing them would mean admitting that state forces committed grave human rights violations.

Is the lack of a chargesheet in your brother's case incompetence or a deliberate strategy for impunity, and why?

I believe the lack of a chargesheet in Umer’s case is not simply administrative incompetence; it is a deliberate strategy to ensure impunity. The system has had over a decade to investigate, file charges, and hold the perpetrators accountable, yet nothing has been done. Even after the court ordered the FIR and the Makhan Lal Koul Commission confirmed that Umer’s death was a custodial killing, the authorities stalled at every step. This deliberate inaction sends a message that those who commit atrocities can act without fear of consequences. Justice has been delayed intentionally, not by accident.

What motivated you to start Umer's social media campaign, and what public reaction has it received?

My biggest motivation has always been my brother himself. He was a minor, and yet he was beaten to death without reason. My father, too, has been a source of courage; he lost his only son, yet he stood firm for Umer’s sake and for accountability in Kashmir. I decided to use social media to keep Umer’s case alive, to update people on the legal process, to remind the world that his story cannot be erased.

This “digital remembrance” is also about resistance. Every post is a way of saying: you cannot erase him, you cannot erase us. It is a record that will exist forever, beyond courtrooms. The response has been mixed, but many people support me, send me prayers, and remind me that, Insha’Allah, one day, justice will be given, not just for Umer, but for every innocent life taken.

How has this decade-long fight, particularly the digital component, affected you personally? What is the most difficult aspect of your digital activism?

The wounds remain fresh for me even after all these years. Every time I post something about his case on social media, it feels like reliving that day all over again. My hands start shivering, my heart races, I panic, and tears roll down. It is not easy at all to keep doing this. The most difficult aspect of my digital activism has been the constant attempts to silence me. I have faced a lot of harassment and threats. My phone has been hacked many times. I have been stopped on the road, called and threatened, and even before one of my press conferences, nearly 10-15 police officials came to my house to intimidate me.

(Article 14 cannot independently verify allegations of threats and harassment.)

How does it feel that a smartphone is the last tool left for seeking justice?

Honestly, it’s both heartbreaking and powerful that a small device like a smartphone has become my last resort for justice. It is my courtroom, my press conference, and my diary of remembrance, all in one. They can censor the newspapers, they can delay the files, they can even try to break me, but they cannot completely stop my voice from reaching people.

How do you connect your brother's case to the broader human rights situation in Kashmir and the struggles of other families seeking justice?

Umer’s case is not just about my brother; it reflects what so many families in Kashmir have gone through. In 2010 alone, more than 120 people were killed by security forces. Families like those of Tufail Mattoo, Wamiq Farooq, and many others are still waiting for justice, just like us. Each of these stories shows the same pattern: excessive force, no FIRs, no accountability, and endless court delays. By keeping Umer’s story alive, I aim to keep the truth of Kashmir’s human rights crisis alive.

What do you believe is the biggest misconception the outside world has about the human rights situation and the fight for freedom in Kashmir?

I believe the biggest misconception the outside world has about Kashmir is that it is only about political slogans or romanticised landscapes. Without realising the human cost, the families who have lost children, the disappearances, and the daily fear that people live under.

Another misconception is that justice exists or that the system protects ordinary citizens. The fight for Umer is not just my fight; it is a fight for every family in Kashmir who has been silenced. My family’s experience of fighting for justice reflects the broader situation of “freedom” in Kashmir because it shows how deeply restricted ordinary people are, not just physically but legally and emotionally.

What is the campaign's goal in the coming years? What would a successful outcome look like, and what message would it send?

With this campaign, I hope to ensure that Umer’s case is never forgotten, never silenced, and never dismissed. In the coming months and years, I want to continue documenting every development, raising awareness about the injustices in Kashmir, and putting pressure on authorities to finally act. A successful outcome for me and my family would be full accountability: that the perpetrators behind Umer’s death are brought to justice.

(Arsalan Shamsi and Mohsin Mushtaq are freelance journalists based in New Delhi.)

Get exclusive access to new databases, expert analyses, weekly newsletters, book excerpts and new ideas on democracy, law and society in India. Subscribe to Article 14.