New Delhi: Act fairly to ensure the rule of law, ensure there is no failure of justice, and avoid future embarrassment.

This was the advice two of its own legal advisers gave to the government of Prime Minister Narendra Modi, pointing out that new rules passed on 25 February 2021 to regulate social-media companies were beyond the scope of existing law and required Parliamentary approval.

In January 2020, two senior legal advisers of the ministry of law and justice advised the ministry of electronics and information technology to first make “suitable amendments” to the Information Technology Act, 2000, before promulgating the now-controversial IT (Intermediary Guidelines and Digital Media Ethics Code) Rules, 2021.

Documents obtained under the Right to Information Act, 2005, by this reporter confirm and provide details of the advice and reveal that the government had set a deadline for the IT rules to come into force: the end of January 2020. The IT ministry removed the names of the two advisers before providing a copy of the records.

Law secretary Anoop Mendiratta overruled the advice, and the changes were made, as the documents revealed, in “the larger public interest”.

Nearly eight months after the objections, as the government faced widespread criticism over its handling of the first Covid-19 wave, the ministry of information and technology got involved, the documents revealed, bringing in streaming platforms, such as Netflix and Amazon Prime, and digital media into the purview of the new rules.

The amendments to the IT Act were then passed three months later without public discussion or debate in and approval from both houses of Parliament, and the IT rules were brought into force under a law that does not mention the media and was never meant to regulate it.

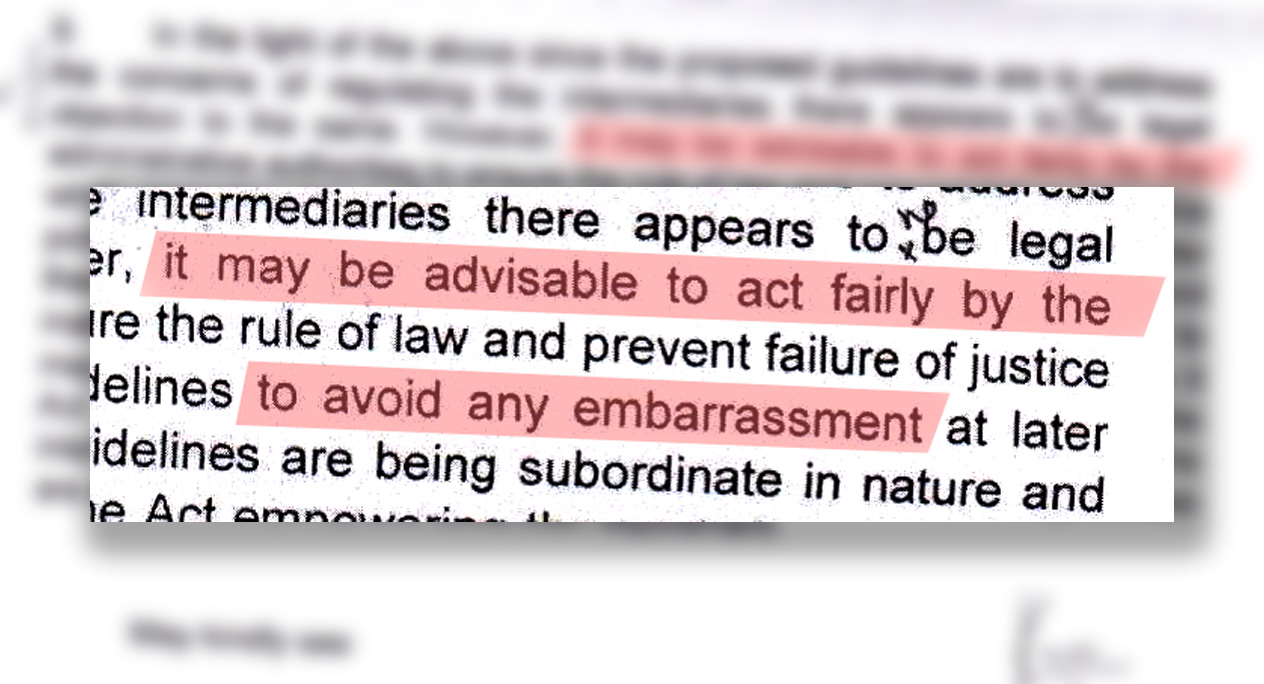

A deputy legal adviser at the law ministry, sensing the potential for misuse, on three occasions early in 2020 said: “It may be advisable to act fairly by the administrative authorities to ensure the rule of law and prevent failure of justice while executing the proposed guidelines to avoid any embarrassment at later (sic) point in time.”

The IT rules stifle the freedom of digital media and streaming platforms and allow the government unprecedented control over social media, critics said, with some even calling it a move towards “totalitarianism”. The rules have been challenged in three high courts, Delhi, Karnataka and Kerala.

The Internet Freedom Foundation, an advocacy group, called the new rules a “Chinese model of online surveillance and censorship”, given by the Executive to itself without due public and Parliamentary process.

Article 14 sought comment from Mendiratta over 12 days over email and calls to his office, but there was no response. We will update this story if he does respond.

Law Does Not Empower Centre To Act Against Intermediaries

On 31 January 2020, 10 days after the IT ministry sent a copy of the draft rules to the law ministry to be vetted, the deputy legal adviser advised the government to “explore the option of bringing suitable amendments in the Act (IT Act)”.

This was because “there is no explicit provision in the Act empowering the central government to make a comprehensive scheme for taking action against the intermediaries'', said the deputy legal adviser, who clarified there was no “legal objection” to the new rules.

The advice was correct because the IT Act does not refer to “action against intermediaries”, described in the law as “...any person who on behalf of another person receives, stores or transmits that record or provides any service with respect to that record”.

The new IT rules now include among “intermediaries” digital news media, social media, such as WhatsApp and Twitter, and OTT (over the top) platforms that deliver streaming services, such as Netflix and Amazon Prime.

This advice of the deputy legal adviser was confirmed and expanded on by a law ministry joint secretary & legal adviser (JS&LA) in a three-page note—a copy of which is with Article 14—on 4 February 2020.

‘Govt Has No Power To Turn Act Into Offence, Prescribe Punishment’

Referring to sec 79 of the IT Act which provides exemption to intermediaries from liability in certain cases, the joint secretary noted: “We are constrained to refer to the limits of liability on intermediary as laid down by the Parliament in Section 79 of the IT Act for his actions being limited to third party information, data or communication link made available or hosted by him”.

The officer explained what this meant: that the intermediary shall be specifically liable only when it is found to be “conspiring, abetting, aiding or inducing the commission of an unlawful act” [section 79(3)(a)] or “if the intermediary fails to expeditiously remove or disable access to such unlawful material on being notified by the Government/its agency or upon receiving actual knowledge [section 79(3)(b)]”.

The joint secretary explained that an intermediary can also be held liable only when it does not provide access, help intercept, monitor or decrypt information, or provide information stored in its computer resource upon receiving an order from the government for interception, monitoring or decryption purposes under sec 69 of the IT Act.

“A bare perusal of the proposed draft IT Rules 2020 give a wide amplitude to the duties and functions of intermediary which prima facie seems to extend beyond the scope of third party information, data or communication link made available or hosted by him” the joint secretary wrote, reminding the Government that the executive had no power to turn “a particular act into an offence and prescribing punishment for it”, an essential legislative function.

The joint secretary said the draft rules suffered “from the vice of excessive delegation”.

He objected to:

The liability thrust upon the intermediary under rule 4(2) [the traceability of messages provision] “does not appear specifically to be supported by the provisions of the (sic) Section 69(3)”.

Liability (punishment) upon the chief compliance officer, as this offence has not been defined in the Act.

The fact that the IT Act does not define terms like “significant social media intermediary”, “social media intermediary” and “social media”. He wrote: “Had the terms been present in the Act, the differentiation or criteria thereof in subordinate legislation can be justified.”

The duty cast upon the intermediary under Rule 4(4) [verify users provision] is not supported by the Act”.

The joint secretary too, like the deputy legal adviser, said the IT ministry should be advised that the Rules “may require certain corresponding amendments in the IT Act 2000 to justify its vires”, which means the officers found the rules to be beyond the powers of the present IT Act and, so, to ensure legal backing, suggested amendments to the IT Act.

The Heavy Hand Of The Government

The new IT rules require intermediaries to comply with an exhaustive list of requirements or face action under “any laws”. The biggest concern is “traceability”, which virtually ends “end-to-end encryption” on social-media platforms, such as WhatsApp and Signal, which will now be required to trace the origins of a message when asked.

Platforms promise encryption to ensure security and privacy to users, prevent identity theft, and code-injection attacks, in which an attacker injects malicious code into a user’s application, leaving user data, security and privacy compromised.

Social media intermediaries are required to now appoint an Indian resident as chief compliance officer (CCO), who will be personally liable if “due diligence” is not observed. But this “due diligence” is not defined and allows the government to decide if it has been met.

Critics have said (here and here) the omniscient threat of government action will lead to self-censorship. Indeed in April, Twitter, on the Centre’s request, took down several posts that criticised the Modi government for its mishandling of Covid-19.

With regard to OTT platforms, the new rules require a “self-regulatory regime”, which will be regulated by the ministry of information and broadcasting and allow its officials to block content “in any case of emergency nature (sic)”.

A Few Tweaks After Objections

After the legal opinion of the two advisers, some changes were made, with regard to traceability and personal liability of the CCO.

The law ministry’s file notings said the CCO would now be made liable only after affording her an opportunity to be heard. On traceability, the IT ministry defined who would be presumed as “first originator” of a message and introduced measures for “protection of interest of users through the appropriate technical measures such as encryption”.

However, the final rules dropped the term “encryption”.

On 21 February 2020, after the IT ministry incorporated a preamble, the joint secretary who had previously raised objections, without further discussion or reason approved the rules, noting that “the preamble to the Rules takes care of most of the concerns raised earlier… the same being in general and greater public interest is justifiable”.

It was not clear how the rules about traceability and verification of users, earlier found to be not supported by the law, were now agreeable to him. “Public interest” seems to be the only justification provided, as the file noted.

After these exchanges, a note on 16 March 2020, with the final rules for notification was sent for “in-principal approval” to the law minister. The note never reached Prasad because the government got involved in what would be a long fight against the Covid-19 pandemic.

Rules Widened to Regulate Digital Media, OTT Platforms

On 11 November 2020, the I&B Ministry, which had nothing to do with the new rules until then, issued a gazette notification that widened their scope. As the file notings reveal, the IT ministry reworked the previously finalised rules to include a mechanism to regulate digital media and OTT platforms.

As per the documents provided to this writer, the law ministry did not seem to comment on the inclusion of OTT platforms and digital media in the IT rules.

Since the updated rules sought to regulate the digital media and OTT platforms, the law ministry only noted there was “no specific provision in the IT Act enabling (sic) to impose any penalty or to take penal action against the intermediaries or digital media”.

The law ministry noted that the updated IT rules would hold the violators liable under the “relevant law” and appropriate action would be taken under that law, not under IT Act, which would have required amendments to the Act.

Finally, while again advising the government to “act fairly” in order to “avoid any embarrassment in future”, the law ministry approved the new rules, which were notified on 25 February 2021.

(Saurav Das is an independent investigative journalist and transparency activist.)