Delhi: Two months after his parents—Nazir Ahmed and Hazara Khatoon—were allegedly abandoned at sea by the Indian government, Joy Nazir, a 24-year-old Rohingya Christian refugee from Myanmar, said he has had no contact with them.

“Days and nights are passing by, but life for us has frozen at that moment,” he said.

Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s government allegedly forced 43 Rohingya refugees—Christian and Muslim—off an Indian naval ship and into the Andaman Sea with only life jackets on 8 May 2025, according to a petition filed by the relatives of two of them in the Supreme Court on 10 May.

They swam to the shore of Myanmar, a Buddhist majority country ruled by a military junta, where Rohingya’s have faced mass killings, rape, and destruction of their villages because of their religion and ethnicity.

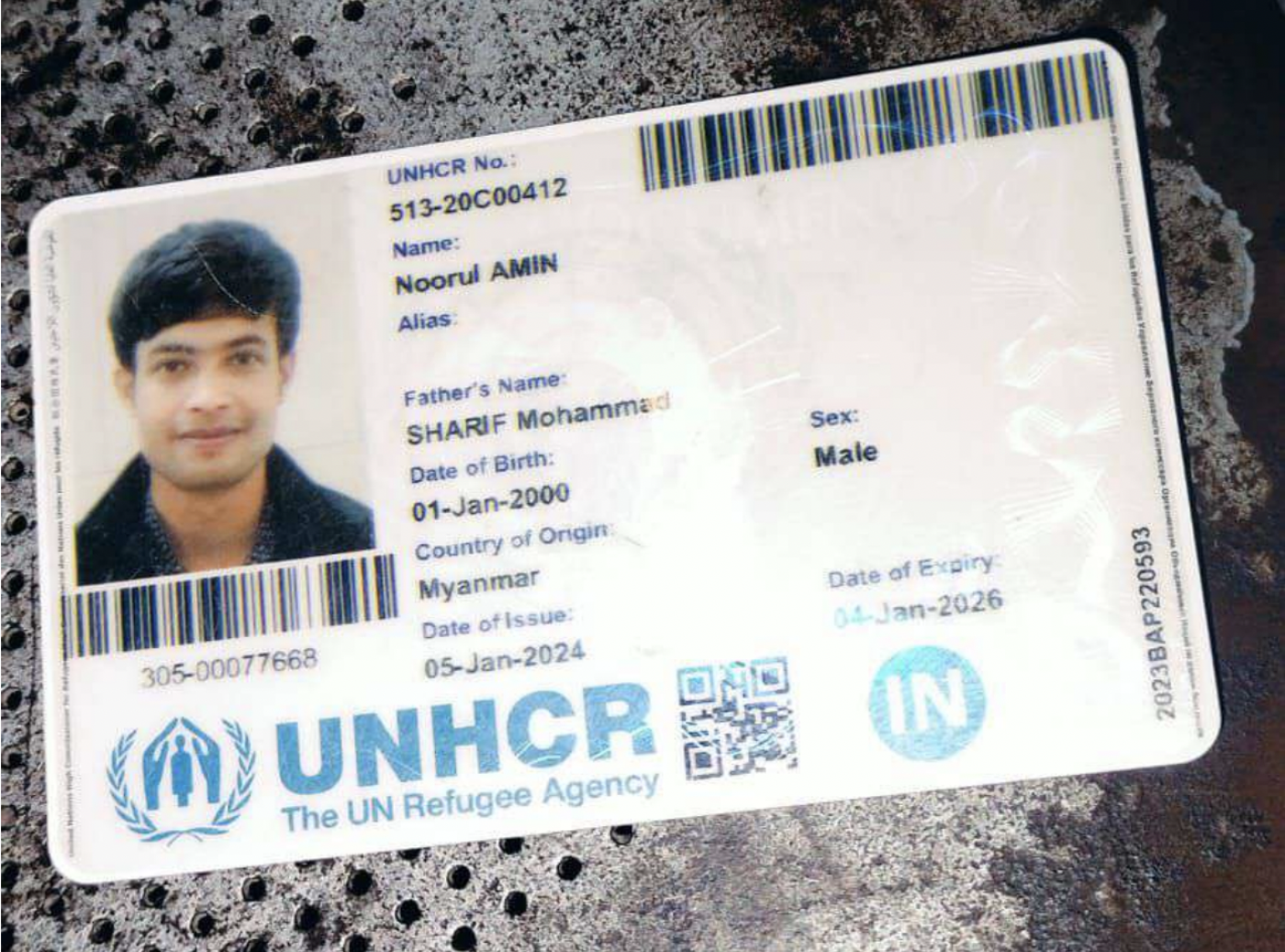

In addition to Nazir, Article 14 spoke with four other refugees—Sadeq Shalom, Sayed Josiah, Mohammed Ismail, and Noorul Amin—who said they had not heard about their families ever since Shalom received a call from his elder brother, Anwar, who informed them that they had arrived in Myanmar on 8 May.

A month after that, on 9 June, Joy Nazir’s brother, David Nazir, spoke with a contact inside Myanmar, who told him the refugees were alive and in a shelter in the Tanintharyi region, the country’s southernmost tip, but he could not organise any direct contact with their family members.

“We pray, we hope, we fear the worst,” said Nazir, describing the situation as “heartbreaking”.

‘Police Slapped, Punched Me’

This second conversation with Nazir took place over the phone on 29 June, close to a month after he and other Rohingya refugees left Delhi, after their relatives were rounded up and illegally deported despite having refugee cards issued by the UNHCR—the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugee—a recognition of their refugee status.

We first met Nazir on 16 May 2025 at his rented accommodation in Hastsal, a low-income neighbourhood in west Delhi, where he had lived since arriving in India as a refugee from Myanmar in 2013.

Fluent in Rohingya, Burmese and English, Nazir was, until May 2025, an interpreter at the UNHCR resettlement programme.

A soft-spoken man of slight build, Nazir showed the lingering scars from a physical assault he alleged he suffered at the hands of police on 8 May, first outside his home and then at the Mayapuri police station in west Delhi.

“They were punching me, slapping me, and pulling my hair. When I asked why, they said, ‘You are a Pakistani terrorist; you are linked with the Pahalgam terror attack,’” said Joy Nazir, referring to the 22 April terrorist attack in which 26 civilians—mostly Hindu tourists—were killed on 22 April in Kashmir.

According to the petition challenging the deportation of the 43 Rohingyas, Mohammad Ismail & Anr vs Union of India, Rohingya refugees were detained overnight at various police stations under the pretext that they would be collecting their biometrics and then moved to a detention centre for Rohingyas in the northwest part of Delhi.

Some of them were allegedly beaten in police custody. Women and children were detained for more than 10 hours without food and without the presence of female police.

A photograph of Nazir with injuries was included in the petition.

A Contact In Myanmar

According to the petition heard by the Supreme Court on 16 May, the 43 deportees included women, children, the elderly and sick people.

The petition said refugees carrying UNHCR cards, which India does not currently accept—were flown from Delhi to Port Blair, forced onto a naval ship blindfolded, with their hands tied.

Close to the Myanmar coast, their blindfolds were removed, hands untied, and they were given life jackets and forced into the Andaman Sea with the assurance that someone would take them to Indonesia, according to the petition and various other accounts (here, here and here).

“Upon arrival, they were devastated to discover they had reached Myanmar,” the petition said.

Joy’s Nazir’s elder brother, David Nazir, 26, said a friend of his in Yangon connected him to a contact in the People’s Defence Force (PDF), the armed wing of Myanmar’s National Unity Government (NUG), which was ousted following the 2021 military coup in Myanmar and is operating in exile.

The contact claimed the deported refugees were alive and in a shelter in the Tanintharyi region in Myanmar’s southernmost tip. In this contested territory, the military junta is reported to have intensified airstrikes in clashes with resistance groups.

David Nazir, a UN interpreter who also left Delhi after the persecution of Rohingya Muslims, said the only time he spoke with the contact was on 9 June, a month after the illegal deportation.

The contact informed him that, despite trying several times, he was unable to facilitate a direct call with his family members.

“Tanintharyi is currently caught in the crossfire of armed conflict between the military junta and armed resistance groups, making it very difficult for the deported refugees to contact their family members left behind,” said Sabber Kyaw Min, a Rohingya activist and founder and director of the Rohingya Human Rights Initiative, a non-profit organisation funded by Rohingya activists in New Delhi, in 2017.

The Myanmar Peace Monitor, run by Burma News International since 2013, reports that in Tanintharyi, on average, around 10 civilians are arrested and killed every month.

“It is unlikely that they have their devices with them, as most of their devices were seized or SIM cards confiscated by the Indian authorities before being dropped into the Andaman Sea, as communicated by a deported family member to a Rohingya refugee here in India,” Kyaw Min said.

David Nazir said his father was partially paralysed and his mother was a diabetic.

“They were picked up wearing just the clothes on their backs, without any spare clothing or their essential medicines. I won’t even be able to see their faces if they die wherever they are,” he said.

On 1 July, senior advocate Colin Gonsalves, who is representing the Rohingya refugees in the Supreme Court, told Article 14 that around three weeks ago, underground sources (pro-democracy groups operating covertly and fighting the military junta) in Myanmar confirmed the refugees were safe but could not speak directly due to security risks, indicating that the refugees face immediate personal danger or further persecution if they communicate openly.

“However, ever since that call, there’s been stark silence,” said Gonsalves. “As of today, we don’t know whether they are alive or dead.”

India’s Changing Stance On Refugees

There are more than 1.4 million Rohingya refugees and asylum seekers globally. According to government records from 2017, there are more than 40,000 Rohingyas in India, mainly staying in Jammu and Kashmir, Telangana, Punjab, Haryana, Uttar Pradesh, Delhi and Rajasthan.

According to the UN, there are 83,499 refugees and asylum seekers in India, the third highest after Bangladesh and Malaysia, with more than 57,700 entering the country since February 2021.

India is not a signatory to the 1951 Refugee Convention, which outlines the rights and protections given to refugees. Still, it has always granted asylum to many refugees from neighbouring countries, afforded protection to people with UNHCR documentation, and respected the international law principle of non-refoulement, which prohibits returning a person to a country where they face a real risk of persecution.

According to the government’s internal guidelines to “deal with foreign nationals in India” who claim to be refugees—issued in December 2011—if a claim of fear of persecution is found to be justified, the ministry of home affairs will grant a long-term visa within 30 days from the date of claim.

In a Supreme Court hearing on a batch of petitions concerning the detention and deportation of Rohingyas on 8 May, the solicitor general of India, Tushar Mehta, said India did not recognise them as refugees and they would be deported according to the law.

Disbelieved By The Supreme Court

After hearing the petition that alleged 43 Rohingya refugees were abandoned at sea on 8 May by the Modi government, the Supreme Court on 16 May called the petition “fanciful” and “a beautifully crafted story” which contained “absolutely no material in support of the vague, evasive and sweeping statements made”.

Justices Surya Kant and N Kotiswar Singh said this despite a recording of a conversation between a deported Rohingya refugee and his family in Delhi on a phone the deported refugee borrowed from a fisherman on reaching Myanmar, a list of the names of the deported refugees, and a condemnation by the UN special rapporteur on the situation of human rights in Myanmar, Tom Andrews.

Justice Kant remarked to Gonsalves, “Every day you come with one new story. What is the basis of this story? Very beautifully crafted story. Please show us the material on the record. What is the material to substantiate your allegations?”

In an interview with Article 14 in May, Gonsalves said the recorded phone call was proof enough.

“The tragedy is that despite the evidence, the Supreme Court not only disbelieved the refugees’ accounts but also mocked them, and this is by far the most cruel thing that the court could have done,” said Gonsalves.

Delhi-based advocate Manik Gupta, who practises in the Supreme Court of India, said such oral observations, though not in the final order, “trickle down” to law enforcement. “They strip away protection, embolden arbitrary detention, and make refugees wary of even approaching courts.”

The petition, clubbed with other petitions related to the detention and deportation of Rohingya refugees in India, is listed for a hearing on 31 July 2025.

UN Goes Silent

In May, the Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights (OHCHR) said, “Alarmed by credible reports that Rohingya refugees were forced off an Indian navy vessel and into the Andaman Sea last week, a UN expert has begun an inquiry into such unconscionable, unacceptable acts…”

UN special rapporteur on the situation of human rights in Myanmar, Tom Andrews, said, “The idea that Rohingya refugees have been cast into the sea from naval vessels is nothing short of outrageous. I am seeking further information and testimony regarding these developments and implore the Indian government to provide a full accounting of what happened.”

On 7 July 2025, Article 14 emailed the OHCHR, seeking a response to the special rapporteur’s request for a response from the Indian government. No reply had been received at the time of publication. The story will be updated if any response is received.

In an email interview, Rama Dwivedi, assistant external relations officer, UNHCR India and the Maldives, said queries about the inquiry announced by the special rapporteur should be directed to the OHCHR.

Article 14 has reached out to Tom Andrews, the UN special rapporteur on the situation of human rights in Myanmar, the ministry of home affairs, and the commissioner of police, Delhi, via emails, but has not received any response. The story will be updated if any response is received.

Article 14 has also reached out to the Delhi Police PRO via WhatsApp and subsequent emails. No reply had been received at the time of publication. The story will be updated if any response is received.

‘The Wait Is Painfully Cruel’

Sadeq Shalom, a 22-year-old career counsellor in the private sector and a refugee with a UNHCR card, whose brother and sister-in-law, Anwar, 23, and Gulbar, 19, respectively, were deported despite having UN cards, said this “blackout” was nothing short of a punishment.

“We are being punished for our identity. We are told that being ‘stateless’ means families can be torn apart and dropped into the sea,” said Shalom.

“We had heard India is a country of ‘unity in diversity’, but the kind of treatment we have received, Indians would think twice before meting out this sort of punishment to an animal,” he said.

Shalom, a Rohingya Christian like Nazir, had left Delhi after Rohingya refugees were detained and deported in May. He spoke with us over the phone on 22 and 29 June.

“The wait is painfully cruel; we are hanging between two options now: to be similarly dropped into the sea or to wait for the news of the death of our loved ones, as we don’t know how they are faring,” he said.

Sayed Josiah, a 28-year-old with a bachelor’s degree in theology, who, like Nazir and Shalom, had left the city after the crackdown in May, spoke with us over the phone.

His brother, sister-in-law, younger sister, and her husband—Sayed Noor, 28, Lal Moti, 22, Gulbar, 19, and Anwar (also Sadeq Shalom's brother), 23—were among the deported.

When we asked him about whether he had friends back in Myanmar who could give any information, Josiah said, “Yes, we have friends (in Myanmar), but not necessarily in the war zone. Our friends have cited security reasons for being unable to visit our deported family members.”

When we asked him about whether his relatives could reach them on social media, Josiah said, “We don’t know what happened to their devices; perhaps they were seized. We have not been able to contact them via social media. Moreover, we ourselves live in constant fear of being picked up, detained, or deported.”

‘Why Were My Parents Thrown Into The Water’

Mohammed Ismail, 44, one of the petitioners, who works as a waste picker, whose sister and niece, Anuwara Begum and Asma Akhter, respectively, were deported, spoke with us at the Shram Vihar refugee camp in Madanpur Khadar, southeast Delhi.

“The deportees were just left swimming in deep waters on an island between Burma (Myanmar) and Bangladesh,” said Ismail. “Is this how the lives of our most beloved must end?”

“She (Ismail’s niece) lived in a small, cramped room where no sunlight enters,” he said. “She was supposed to get married a day after, had she not been deported.”

Ismail said his family had protected the niece from “a war zone” until now (as they fled Myanmar in fear of persecution), but she couldn’t be saved.

“And today, we don’t even know whether that precious child is alive or dead. She may have been a Rohingya, but she is precious to us,” said Ismail. “Was she such a threat to the Indian State?”

“Write my name; keep writing about us. As it is, we don’t exist. Better to talk than disappear in oblivion,” he said.

Noorul Amin, 25, the second petitioner, whose father Mohammad Sharif, mother Laila Begum, elder brother Syedul Kareem, younger brother Kairul Amin, and his wife Sahida, were rounded up from Kanchan Kunj at Madanpur Khadar in southeast Delhi.

Amin, a daily wage earner living in a low-income neighbourhood in west Delhi, said getting work has become challenging since the May crackdown.

Appealing to the authorities to bring back his parents, Amin said, “It is giving me nightmares to think about the ordeal they must be going through. Tell my story to the entire world.”

“Why were my parents thrown into the water?” he said. “Who will be responsible if they die in a war zone? Are our lives so insignificant, so small?”

Torture, Abuse Alleged

The deportation followed a systematic crackdown that began on 6 May, marked by police brutality and public humiliation of Rohingya refugees.

Article 14 spoke with two refugees—Noorul Amin and Joy Nazir—who alleged being subjected to verbal and physical abuse.

Noorul Amin recounted the evening of 6 May at his rented room in Budella, Vikaspuri, west Delhi.

It was around eight at night and he was at the Deen Dayal Upadhyay Hospital in Hari Nagar, west Delhi, tending to his wife, who had suffered a miscarriage, when a policewoman from Kalinidi Kunj police station came into the hospital and told doctors not to treat Rohingya patients, Amin alleged.

According to Amin, the policewoman said, “They are ghuspetiya (infiltrators). Why are you treating them? They are Muslims; they’ve come from Myanmar to destroy our country.”

Amin alleged that the officer, along with two police personnel who arrived from Kalindi Kunj police station looking for Amin’s mother, physically assaulted him and dragged him and his wife to the police vehicle.

Amin further alleged that they took the couple to Vikaspuri police station, where “Police Madam” asked whether this “miya-bibi” (husband-wife) pair was on the list of Rohingya refugees in their jurisdiction. The policeman present confirmed they were and noted that community leaders regularly updated police on their whereabouts.

When Article 14 contacted the said policewoman on the phone on 27 May, she refused to share her name or acknowledge any Rohingya refugee.

This reporter visited Kalindi Kunj police station on 24 June 2025, seeking a response from the station house officer (SHO) on the issue of the policewoman from this station taking Noorul Amin and his wife to the Vikaspuri police station and using Islamophobic slurs against them.

The SHO asked this reporter to provide evidence, inquiring whether this incident had been reported anywhere or to disclose the name of the victim. At the time, this reporter felt revealing Noorul Amin’s name to the local police personnel would make him vulnerable to retaliation.

On 11 July and 15 July 2025, Article 14 sent emails to the station house officer (SHO) of the Kalindi Kunj police station, seeking a response on the alleged violation of due process of law and the Rohingya refugees being subjected to Islamophobic slurs and physical assault.

No response has been received at the time of publication. This story will be updated if there is any response.

This reporter also visited the Vikaspuri police station on 26 May and 27 June 2025, seeking a response from the SHO on the issue of the concerned Kalindi Kunj policewoman bringing Noorul Amin and his wife to the Vikaspuri police station and the officer using Islamophobic slurs.

This reporter waited for two and a half hours, but the SHO was unavailable for comment.

‘I’m A Refugee. You Have My UNHCR Card’

At his home in west Delhi, Joy Nazir recounted that his ordeal began on the night of 8 May 2025 when he was at Barkat Ram Hospital with his ailing wife and two-year-old child, and started receiving calls from his landlady, who informed him that the police were looking for him.

When he reached his landlady’s residence, a few metres away from his home, the police personnel allowed Nazir to hand over his child to his wife before taking him into custody.

Then, Nazir said, three police personnel surrounded him, raining blows on his body the moment he was alone on the street outside his residence.

The police invited two bystanders to join the assault, said Joy Nazir.

When the police identified Joy Nazir as “Pakistani”, they asked: “Kya hum bhi do thappad maar sakte hain?” (Can we also give him two slaps?). The police said, “Why only two? … Beat him as much as you want.”

Nazir said he was pushed to the wall and kicked in his private parts.

Nazir alleged that the verbal and physical abuse went on past four in the morning at the Mayapuri police station, where he said he was stripped, beaten, made to jump while in pain, denied water, and forced to prostrate before an “Indian citizen”, who was served tea and snacks to “tease” him.

Article 14 sent emails to the SHO of the Mayapuri police station on 8 July 2025 and 9 July 2025, seeking a response to Nazir’s allegation.

No response has been received at the time of publication. This story will be updated if there is any response.

As his ordeal continued, Nazir said, the police not only called him a “Pakistani” without any evidence but also said he deserved to be tortured and didn’t “deserve any human treatment” on account of his Pakistani identity.

Nazir said that he kept pleading, “I’m not Pakistani. I’m a refugee. You have my UNHCR card. We’ve been living there since 2013.”

(Sanhati Banerjee is an independent journalist and a content consultant.)

Get exclusive access to new databases, expert analyses, weekly newsletters, book excerpts and new ideas on democracy, law and society in India. Subscribe to Article 14.