New Delhi: Banojyotsna Lahiri, a Delhi-based researcher, recalled that one of the first judges of the Supreme Court who was assigned her partner Umar Khalid's bail petition said it would take “two minutes” to complete the proceedings.

Khalid, a 36-year-old political activist, accused of instigating Hindu-Muslims riots in Delhi in February 2020, had filed his bail petition in May. It was 12 July when a bench of Justice AS Bopanna and Justice M M Sundresh said it was a matter that “may take one or two minutes” when the State asked for more time to file a response to the chargesheet running into “thousands of page” even though the court was convening after more than a month-long summer break.

When the judges refused to extend the next hearing beyond 24 July, Banojyotsna felt assured that the proceedings in the country’s highest court would take a fraction of the time it took for Khalid’s bail hearings to be completed in the district court and the Delhi High Court.

With both sides making more extensive arguments than are typical at the stage of bail, the State seeking adjournments as a delaying tactic, scheduling conflicts of lawyers and judges, and illnesses as well as courts slowing during the pandemic, it took six months in the high court for proceedings (May 2022 to October 2022) and eight months in the sessions court (August 2021 to March 2022) to get a verdict.

Despite the demonstrably weak case against Khalid and the courts granting bail to some of his co-defendants, the same judges denied bail to Khalid, whose stature as a symbol of resistance to the authoritarianism and majoritarianism that has thrived under Prime Minister Narendra Modi and the Bharatiya Janata Party has grown in his three years and three months behind bars.

The Supreme Court, contrary to its own jurisprudence of hearing bail pleas quickly (here and here), has surpassed lower courts with a delay of seven months in hearing Khalid’s arguments for bail even though the matter has been listed 10 times before different judges since May 2023.

“Every time he calls on that day, I have to say 'aaj bhi nahin hua, yaar. Chaar hafte baad ab dekhehe'. (It did not happen even today. We’ll see after four weeks.) It is difficult for me to convey this every time, and I’m sure it is difficult for him to hear it,” said Lahiri.

“Although he has kept up his spirit and tries never to sound despondent, I can only imagine his dismay,” she said.

The legal trajectory of Khalid’s petition shows that it is bouncing between different judges of the Supreme Court, with the matter being deferred over and over. Sometimes, the delays have been caused when lawyers have sought adjournments, but other times, when both sides are present and ready to argue, the judges have run out of time.

The more recent cause for delay is the consternation over the matter ending up before a bench headed by Justice Bela Trivedi, who, Article 14 reported, has had several politically sensitive cases assigned to her in the past few months by the Chief Justice of India, D Y Chandrachud, contrary to the rules of assignment of the Supreme Court.

Khalid's bail petition, now tagged along with several petitions challenging sections of India’s anti-terror law, the Unlawful Activities Prevention Act (UAPA), 1967, and matters related to the Tripura police registering cases against people who wrote about the communal violence in the state in October 2021, will now come up for a hearing on 10 January.

Supreme Court advocate Shahrukh Alam, a lawyer in a matter challenging the UAPA and some of the Tripura cases, said the bail matter was different.

“One is a challenge to the UAPA, which is much more comprehensive and constitutional,” said Alam. “The bail is much more fact-based and deals with the law as it applies today without going into the constitutionality, saying the provision should not apply to the facts of this case. And it is a matter of human liberty. Someone is in jail.”

It Could Take A While

The proceedings were complicated by Khalid filing a writ petition challenging section 15 (1) (a)—terrorist act and section 18—punishment for conspiracy act, sections under which he is chargesheeted, which was tagged to his bail petition, and both were tagged with the earlier batch of UAPA and Tripura petitions.

Instead of Khalid’s petition travelling with the earlier petitions listed before the senior judges, including Chief Justice Chandrachud, who was hearing the Tripura cases, those older cases started travelling with Khalid’s petitions and ended up before Trivedi.

The rules of assignment say that if a matter has been listed before a bench, it will be listed before the senior judge of the bench the next time if they are available. If a matter has been tagged with an earlier matter, then a new matter goes to the bench, taking up the earlier matter.

While the state now wants to argue before Trivedi’s bench, and the judge insists on hearing them all, lawyers in the different petitions have objected to how all these matters have ended up before her bench and want them to return to a constitutional bench comprising senior judges.

In a letter to the registrar of the Supreme Court, senior advocate Prashant Bhushan said that his case was about the Tripura police registering a first information report (FIR) under the UAPA against a person who had published a fact-finding report about the communal violence in 2021 and a journalist who had criticised state inaction—Mukesh & Ors. vs State of Tripura & Ors—and sought to quash the FIRs and challenged sections 2(1)(o)—definition of unlawful activity, section 13—punishment for unlawful activities, and section 43(d)(5)—a provision that restricts bail, and that it was first heard by a three-judge bench led by N V Ramana, the chief justice in 2021.

Another case arising from allegedly false FIRs registered by the Tripura police came up before Ramana and then went to Chandrachud, who tagged both cases. Then, two other challenges to the UAPA in September and October 2022 were listed before UU Lalit, the chief justice at the time. All the tagged matters were listed before Chandrachud, who became the chief justice in November 2022.

Then, after being listed before Justice Aniruddha Bose and Justice Bela Trivedi, it was listed before the junior of the two judges.

Inquiring if “there is any administrative order specifically directing the matter to be placed” before these benches, Bhushan wrote, “the petitioners would be constrained to avail appropriate legal remedies.”

Speaking to Article 14, Bhushan said, “All should have gone to Chandrachud, or it should have gone to Bose, but it has gone to Bela Trivedi. We don’t know how this is happening. Whether the registry is doing it or the chief justice is.”

On Khalid’s bail petition, Bhushan said, “Many bail petitions are not being heard for a long time, and the problem is even more serious in the lower courts. There is apathy, not realising the importance of liberty.”

Alam said that the “pendency of cases” was also a reason for the delay in bail hearings, with matters getting listed after a gap of one month, which has also happened many times in Khalid’s case.

Despite attaining a high rate of disposal under Chandrachud, 80,000 cases are pending before 34 judges before the Supreme Court, which attained its full strength only a month ago after three vacancies since June.

Khalid is not alone.

Shoma Sen, a 66-year-old English professor and one of the 15 accused of having Maoist links and inciting riots in Bhima Koregaon in Maharashtra on 1 January 2018, has been incarcerated in Byculla jail in Mumbai since June 2018 for more than five years.

Sen, who is in poor health and has been fighting for bail in the lower courts since December 2018 and in the Supreme Court since April, will now be heard on 10 January 2024.

The Backstory

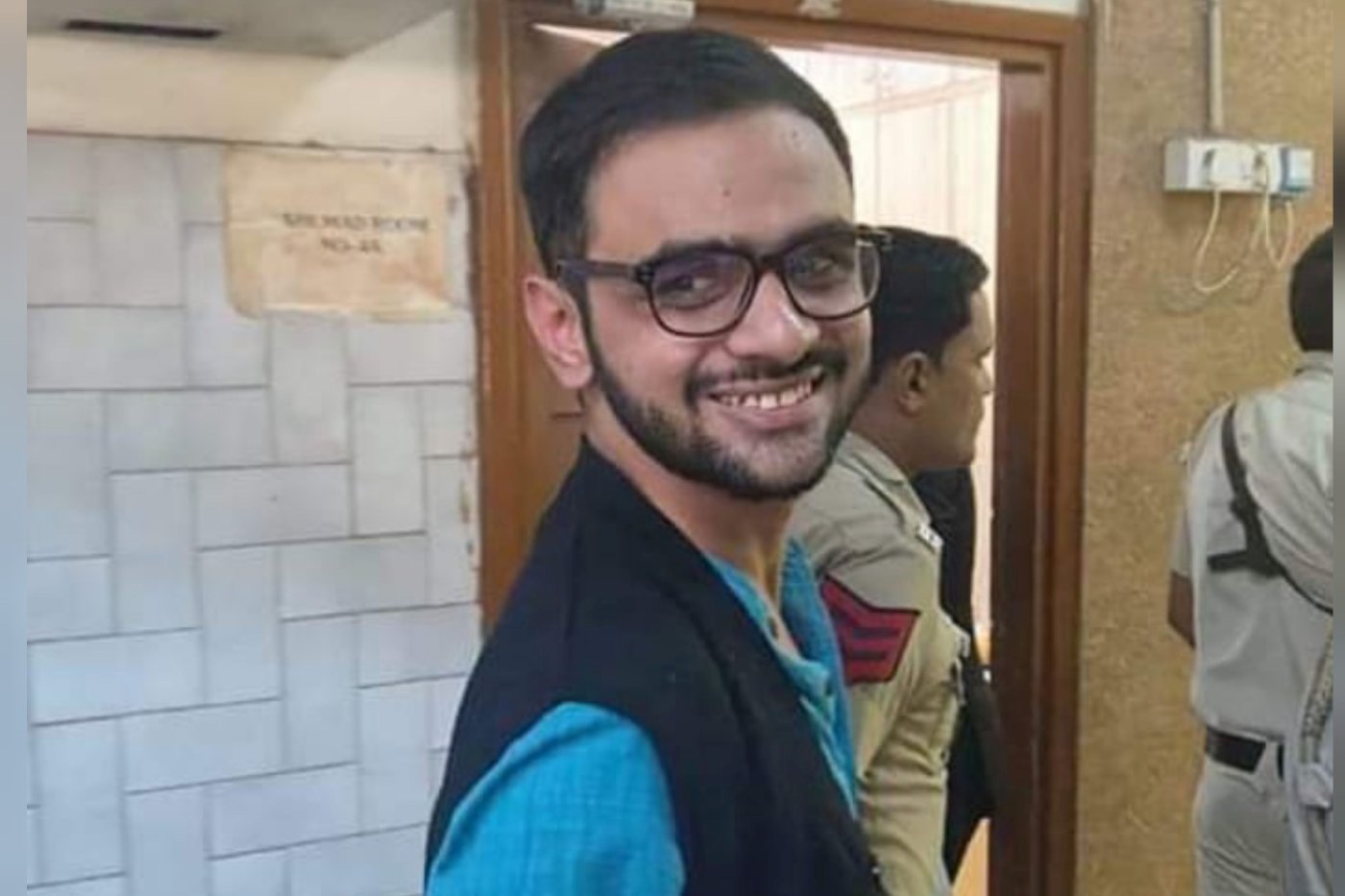

Article 14 has previously reported that the Delhi police case against Khalid, a PhD from Jawaharlal Nehru University, is built on conjectures and inferences, with no evidence so far that he was behind planning the Delhi riots that claimed the lives of 53 people, three-quarters of them Muslim. Of the 20 people chargesheeted in the case, 18 are Muslim.

The Delhi High Court order denying bail to Khalid in October 2022 was inconsistent with its order a year earlier, granting bail to three of Khalid’s co-defendants, with Justice Siddharth Mridul, a judge in both cases.

While granting bail to Devangana Kalita, Natasha Narwal, and Asif Iqbal Tanha in June 2021, the court said the state, “anxious to suppress dissent”, had blurred the line between the “right to protest” and “terrorist activity” and the UAPA case was not prima facie made out.

In Khalid’s case, the judge nitpicked at phrases like “inquilab salam” (revolutionary salute) and “krantikari istiqbal” (revolutionary welcome) in the only speech the Delhi police had produced for the alleged mastermind of the riots and made some tenuous connection with the French Revolution.

The speech has been available online since it was made in Amravati, Maharashtra, on 17 February 2020.

Khalid’s lawyer, advocate Trideep Pais, who argued in the sessions court and the High Court, showed how witnesses had lied or changed their accounts to fit a predetermined narrative to delegitimise the movement against the Citizenship Amendment Act, 2019 (CAA), a people’s movement led by Muslims, which the police say was a front for the riots.

The anti-CAA movement opposed allowing migrants of all faiths from Afghanistan, Pakistan and Bangladesh, except Muslims, a path to Indian citizenship.

The speed with which it grew and spread across the country surprised Prime Minister Modi’s government. Khalid, who had become a vocal critic of the ruling Bharatiya Janata Party and its Hindu majoritarian policies that allowed for widespread anti-Muslim hate crime and hate speech by Hindu extremists and even BJP leaders, was seen as a driving force behind the movement.

Khalid was arrested in September 2020.

Reiterating almost every year that bail petitions must be heard as expeditiously as possible, the Supreme Court in 2021 said the “liberty of an individual is sacrosanct”, in 2022 said bail applications are “not to be posted in due course of time”, and in 2023 said that bail order should not be too long or too late because both violate personal liberty.

“Other than the dates when lawyers asked for adjournments, there were days when both parties were there, and we were ready to argue, but they just didn’t hear us, and they just gave us a date,” said Lahiri, Khalid’s partner.

“The day when Dipankar Datta and Bela Trivedi were sitting, Kapil Sibal just pleaded that give us 20 minutes… it wasn’t that there was no time,” she said. “There was time. It was just 3:30, and usually, they sat till 4. The day before, they had sat till four or 4:15, so it was not that there was no time. And they gave us another long date.”

Going Against What It Has Always Said

In Union of India vs K.A. Najeeb (2021), the Supreme Court said that despite a restriction under the UAPA for granting bail for certain crimes under the Act, bail had to be given if the accused's fundamental rights were violated. The right to a speedy trial was one of those rights.

In Ritu Chhabaria vs Union of India (2023), the Supreme Court said that default bail was a fundamental right. If the police still need to complete their investigation, they cannot keep filing supplementary chargesheets to keep the accused in jail.

While demolishing most of the cases against Kashmiri journalist Fahad Shah last month and removing the terror charge against him, Justice Atul Sreedharan of the High Court of Jammu & Kashmir and Ladakh built on the Supreme Court’s ruling on Najeeb, saying that even in UAPA cases it was necessary to consider two conditions while granting bail: was there a need to arrest and is there a need to keep them in jail.

How It Started

In the first hearing on 18 May, Justice A.S. Boppana and Justice J Hima Kohli gave the Delhi police six weeks to reply to Khalid’s bail application, which included five weeks of the court closing for the summer from 22 May to 30 June.

In brief remarks, Khalid’s lawyer, senior advocate Kapil Sibal, said Khalid was not in Delhi on the day of the incident. When Boppana asked if the matter should be listed before a vacation bench, Sibal said it should be heard after the recess.

At the next hearing before Justice Boppana and Justice M M Sundresh on 12 July 2023, the state sought more time, and it was listed 12 days later on 24 July 2023.

Appearing for the central government, the additional solicitor general of India, S V Raju, said the chargesheet was voluminous, running into thousands of pages. Sibal pointed out that Khalid had been incarcerated for two years and ten months.

At the next hearing on 24 July 2023 before Justice Bopanna and Justice Bela Trivedi, the matter was moved for a week because Sibal sought an adjournment for personal reasons.

At the next hearing on 9 August before Justice Boppana and Justice Prashant Kumar Mishra, Justice Mishra recused himself, and the matter was listed eight days later on 17 August. But it was listed before the same bench and not heard. The state’s counter affidavit was taken on the record.

On 14 August, Raju requested an adjournment for two weeks for personal reasons.

At the next hearing before Justice Aniruddha Bose and Justice Bela Trivedi on 18 August, the bench said the matter should be listed on a non-miscellaneous day—Tuesdays, Wednesdays and Thursdays—the days when cases that require lengthy hearings are taken up, and it was listed after two weeks.

At the next hearing before Justice Bela Trivedi and Justice Dipankar Datta on 5 September 2023, Sibal sought an adjournment, and the matter was listed for a week later.

At the next hearing before J Aniruddha Bose and Justice Bela Trivedi on 12 September 2023, as per the petitioner’s side, the Bench said the bail hearing would take some time as they would have to see necessary documents.

The Bench directed the petitioner to file written submissions showing how offences under chapters IV and VI of the UAPA are not made out. The matter was listed for a month later.

At the next hearing before Justice Bela Trivedi and Justice Dipankar Datta on 12 October 2023, as per the petitioner’s side, the Bench said the bail hearing would take some time. Since they did not know if they would be sitting in the same combination, they did not want to hear any matter partly. Khalid’s counsel said the petitioner had been in custody for over three years and they should be allowed to start.

In its order, the Bench said, “Due to paucity of time, the matter was not taken up today.” The matter was listed for 1 November 2023, and it was to be heard in the first five matters.

Challenging The UAPA

Before the next hearing, Khalid filed a writ petition challenging section 15 (1) (a) and section 18 of the UAPA.

When the writ petition was listed before Justice Aniruddha Bose and Justice Bela Trivedi on 20 October 2023, on the petitioner’s request, the Bench tagged it with other matters in which the constitutional validity of several provisions of the UAPA was challenged.

The next day, on 21 October 2023, Khalid’s bail petition was listed, as per the weekly list, the bail petition was to come up before a bench comprising Justice Bela Trivedi and Justice SVN Bhatti on 1 November 2023, as per the petitioner’s side. But when they checked the main cause list for 1 November 2023, the bail matter was no longer listed despite the order on 12 October 2023 saying it would be heard in the first five matters.

On 30 October 2023, the petitioner learnt the writ petitions connected to their challenge to the UAPA were listed before a Bench headed by Justice Vikram Nath and Justice Rajesh Bindal, but Khalid’s petition was not one of them.

That same day, the petitioners learnt that Khalid's petition had been listed before the Bench of Justice Aniruddha Bose and Justice Bela Trivedi. Then, all the matters challenging the UAPA were listed before the Bose and Trivedi Bench.

On 31 October 2023, Bose and Trivedi tagged Khalid’s bail application with petitions challenging the constitutional matters together and listed all the matters on 22 November 2023.

The judges said they would not have time to hear the bail application scheduled on 1 November 2023 (despite the order on 12 October 2023 saying it would be heard in the first five matters).

On 14 November 2011, Khalid’s bail application, his petition and other petitions challenging the UAPA were listed before the bench of Justice Bela Trivedi and Justice Satish Chandra Sharma on 22 November 2023.

Where It Is Going

On 22 November, however, the matters were not listed because Justice Bela Trivedi was sitting in a special three-judge bench hearing PMLA—Prevention of Money Laundering Act, 2002—review petitions.

Some of the matters listed before the bench of Justice Bela Trivedi and Justice Satish Chandra Sharma were listed before Justice Sudhanshu Dhulia and Sharma, but Khalid’s petition was not one of them.

Khalid’s matter was listed before Trivedi and Sharma on 28 November 2023, but due to the unavailability of Sibal for Khalid and Raju for the state, the matter was adjourned till 10 January 2024.

The Bench had scheduled the case for 6 December, but because Sibal had to appear in another case on the same day, it was scheduled for 2024.

“We just kept waiting from one date to another,” said Lahiri. “That is all that happened.”

(Betwa Sharma is the managing editor of Article 14.)

Get exclusive access to new databases, expert analyses, weekly newsletters, book excerpts and new ideas on democracy, law and society in India. Subscribe to Article 14.