Just months after dismissing reports of the Indian government forcibly abandoning 40 Rohingya refugees at sea as a “beautifully-crafted story”, Justice Surya Kant has reaffirmed—this time as the Chief Justice of India—the Supreme Court’s disinclination to show any sympathy towards the stateless community.

On 2 December 2025, while hearing a habeas corpus (literally, produce the body) writ petition on the disappearance of five Rohingya refugees from the custody of the Delhi police, he questioned the Rohingya’s legal status as refugees in India.

The Chief Justice also likened them to “intruders”, according to reporting by Livelaw, echoing language used by the Prime Minister and home minister.

Chief Justice Surya Kant rhetorically asked if India should “give them (Rohingya) a red carpet welcome” and extend “all facilities”. The remarks have drawn outrage, with a group of retired judges, practicing senior lawyers and noted civil society activists calling them “contrary to core constitutional values”.

The petitioner, Rita Manchanda, a veteran human rights activist with a rich background in asylum activism, sought from the apex court a direction to the Indian government to “produce and disclose the last known location and whereabouts” of the five missing refugees.

Argued by Ujjaini Chatterji, a human rights lawyer who works closely with victims of asylum and citizenship deprivation, the petition, using independent primary research and secondary accounts, reveals how the Delhi Police surreptitiously detained the refugees on 6 May from the Madanpur Khadar area in India’s national capital under the pretext of correcting biometric errors.

Promising to release them soon after their detention, the police did not, and the group of five refugees, which includes two women, remains untraceable.

That their custodial disappearance overlaps with the rough period of time in May when the Narendra Modi government reportedly dropped a group of 40 Rohingya in the Bay of Bengal could just be an unfortunate coincidence.

Their family and community members do not believe that to be the case.

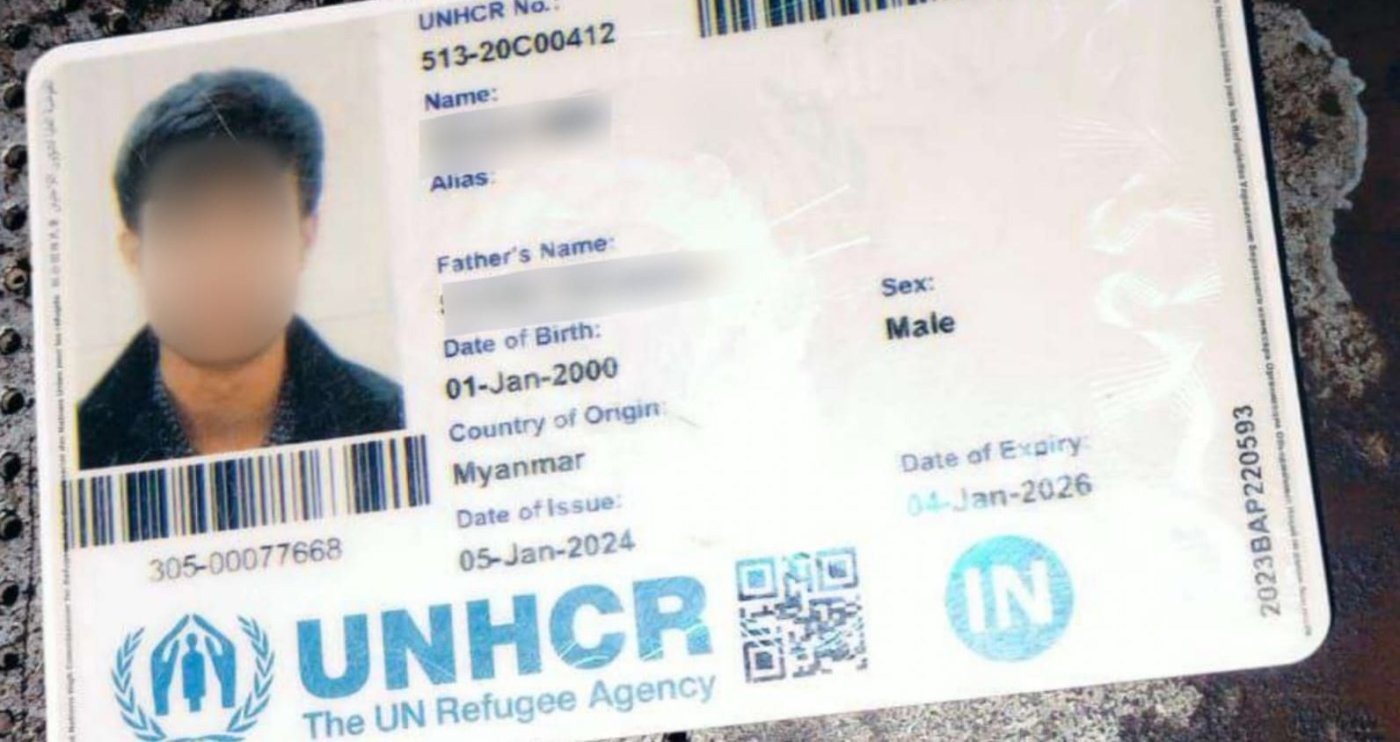

The petition also notes that all five possessed United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) cards issued after a stringent refugee status determination process.

The two-judge division bench led by Justice Kant appeared to not only disregard these crucial facts, but also tacitly justify the refugees’ extrajudicial expulsion from Indian territory.

A Distracted Court

By focusing on the legal status of the refugees, the Supreme Court bench completely deviated from the crux of the writ petition filed by Manchanda, that is, custodial disappearance.

Five individuals missing from police custody should alarm any court in this country, regardless of their legal status or nationality. Arrests, detentions, and deportations are strictly legal procedures that need to abide by established legal norms, even in the case of the most hardened criminals, which the refugees are not.

Failure to do so blurs the thin but critical line between detention and abduction, and between deportation and forced expulsion.

One expects a bench at the Supreme Court led by its Chief Justice to be cognisant of these basic, non-negotiable norms of constitutional democracy. Yet, it appeared more bothered about the rights of the all-powerful state (to deport illegal immigrants), rather than those of five stateless individuals who have little to no legal safeguards in any country, including their home country of Myanmar.

On the scale of legal morality, this weighs on the skewed side. But, even in privileging the government’s sovereign rights, the Supreme Court has a responsibility to emphasise due process.

In this case, the very concept of due process seems to have been torn asunder, even as state authorities put up a facade of legality. This was most clearly demonstrated by the State itself.

Allowing State Opacity

In a status report submitted to the Delhi High Court during a previous hearing on the same petition by Manchanda, which this author has seen, the union government confessed that it had “repatriated” 40 Rohingya refugees to their “origin country Myanmar” because “they were illegal migrants in India”.

However, it did not furnish any proof of whether the formal deportation process was followed, which includes, among other things, a Nationality Status Verification (NSV) protocol with the home country.

Neither did it present any official deportation order; it merely cited a home ministry memorandum published on 2 May that gives sweeping powers to authorities to detain and deport foreigners.

Indeed, the memorandum itself stipulates that the Bureau of Immigration make deportation records public and that border forces furnish reports of deportations, neither of which appears to have happened in this case.

Indeed, the government’s own status report to the Delhi High Court cited a 2021 Supreme Court order on two other Rohingya refugees, which itself directs the government to follow due process while deporting refugees.

In essence, while the government accepted that it had deported 40 Rohingya refugees to Myanmar following due process, it refused to provide formal documentation to show for it, in contravention to its own directives.

It is incumbent on the Supreme Court, then, to see through the haze and compel the state to come clean. As the sentinel on the qui vive— watchful guardian of fundamental rights, including the rights to life and equality before law that apply to all individuals (and not just Indian citizens)—the court must intervene to restore accountability every time the executive attempts to evade it.

In this case, however, the Supreme Court gave ample space to the State to hide behind an opaque curtain of arbitrary executive memorandums, vague immigration norms and misrepresented court judgements. In a subsequent hearing of the case on 16 December, the court sought a short affidavit from the state. One hopes the bench uses the same to re-establish transparency and accountability on the matter.

Deportation Or Trafficking?

This opacity isn’t merely a moral or normative concern.

Covert removal of individuals from Indian territory effectively amounts to, as the petitioner argues, “trafficking rather than lawful deportation.” Without proper executive oversight or legal supervision, deportees are exposed to a wide range of dangers—from capture by sex traffickers and hostile armed groups to being eliminated at the border by state security forces.

Media reports have indicated that the 40 refugees that India dropped at sea near the southeastern coast of Myanmar in May washed ashore directly into an active warzone, eventually falling into the protective custody of an anti-military armed group known as Ba Htoo Army. Their exact condition remains unclear.

The Rohingya are also not just one of the most trafficked communities in the world today, but also remain vulnerable to forced recruitment by armed gangs in the refugee camps of Bangladesh and the Myanmar military in Rakhine State.

The Supreme Court is expected to make itself aware of these crucial realities while adjudicating Rohingya-related cases, for they can have serious implications on the lives of refugees who are deported to Bangladesh or Myanmar.

By attributing malicious intent to Rohingya refugees and likening them to tunnel-diggers, the Court stands to further dehumanise a community that continues to face extreme dehumanisation, deprivation and rejection not just in Myanmar, but across Asia.

Can such a hapless group of people be called ‘intruders’? Allusions such as these only seem to echo the right-wing, xenophobic rhetoric against Muslim migrants and refugees in India.

They obfuscate the harsh reality of Rohingya displacement from Myanmar’s strife-torn Rakhine State, where a combination of various ethno-majoritarian Buddhist aggressors have forced the stateless Muslim community to flee to other countries in South Asia and beyond.

In the 2016-17 period, particularly, more than 800,000 Rohingya fled to Bangladesh after the Myanmar military conducted a months-long campaign of brutal violence against the community, which according to an UN investigative panel, carried ‘genocidal intent.’

Myanmar is currently on trial at the International Court of Justice for violating the Genocide Convention.

By no moral, political or legal standard should people who are subjected to such brutal violence be called ‘intruders’.

Even while fleeing to safer shores, many of them have perished at sea. Only last month, at least 29 Rohingya died when their boat capsized off the coast of Malaysia.

Politics Over Law

The Supreme Court also counteracted the petition by emphasising the need to tend to the poor within India, rather than refugees from outside.

Such arguments do not belong in the highest constitutional court of India, but perhaps, in the morass of partisan politics.

They fall in the same bracket as the xenophobic campaigns that unfolded in the run up to this year’s assembly election in Delhi, which saw both the Bharatiya Janata Party and the Aam Aadmi Party use the distorted logic of competitive resource allocation to provoke public sentiments against the city’s Rohingya refugees.

One wonders how five hapless refugees could hinder the mighty Indian state’s ability to alleviate poverty in the country. Has the Supreme Court succumbed to what the Indian-American anthropologist, Arjun Appadurai, has called the “fear of small numbers?”

The Supreme Court must not only impress on the State to produce the five missing refugees in this case, but also take an all-rounded view of the broader Rohingya issue.

What does this mean? It means not ignoring the fact that many Rohingya refugees—most certainly the missing five—hold refugee identity cards that were issued by an UN agency with rigorous vetting standards.

It means recognising that India is not a state party to the 1951 Refugee Convention, and yet upholding the UNHCR’s informal mandate in India and the sanctity of customary international legal norms like non-refoulement that obligate the state to protect vulnerable refugees from forced deportation to countries where they face an active risk of persecution or death.

It means accounting for the Rohingya’s social, political and economic deprivation in Myanmar and other host countries in every judicial matter pertaining to the community. It means recognising the absence of official citizenship status for the Rohingya in Myanmar, which makes a genuine NSV process—and thus, legal deportation—nearly impossible.

It also means summoning the prevailing facts on the ground in Rakhine State, where an ongoing civil war between the Burmese army and the Rakhine Buddhist Arakan Army (AA) has made life for the Rohingya exceptionally perilous and dimmed prospects for safe, dignified and voluntary repatriation.

One expects the Supreme Court to adjudicate matters on the lives of vulnerable refugees with empathy, not political rhetoric. Yet, in recent years, the court seems to have abdicated its humanitarian, rights-oriented mandate in favour of a more State-centric, security-focused judicial orientation that frames refugee bodies as threats to the Indian state and its ‘sensitive’ borders.

The implications of this have been troubling, as the Supreme Court now appears to be downplaying something as serious as custodial disappearance.

(Angshuman Choudhury is a doctoral candidate in Comparative Asian Studies jointly at the National University of Singapore and King’s College London. He is also a Board Member at the Development and Justice Initiative.)

Get exclusive access to new databases, expert analyses, weekly newsletters, book excerpts and new ideas on democracy, law and society in India. Subscribe to Article 14.