Dehradun: The Chipko movement, born in early 1973 in the Himalayan state of Uttarakhand, reaches its 50th year in 2023.

Chipko—which translates as "to hug" in Hindi—got its name from one of the protesters and folk singers, Ghanshyam Sailani, who, in the early 1970s, recited his self-composed poem at a gathering—"Chipkapaedon par ab nakatyandya, Pahadon ki sampatti ab nalutyandya," (hug the trees to protect them from axes, let’s preserve the true wealth of our hills). That became a clarion call for the people of Uttarakhand to hug their trees and save them from getting axed.

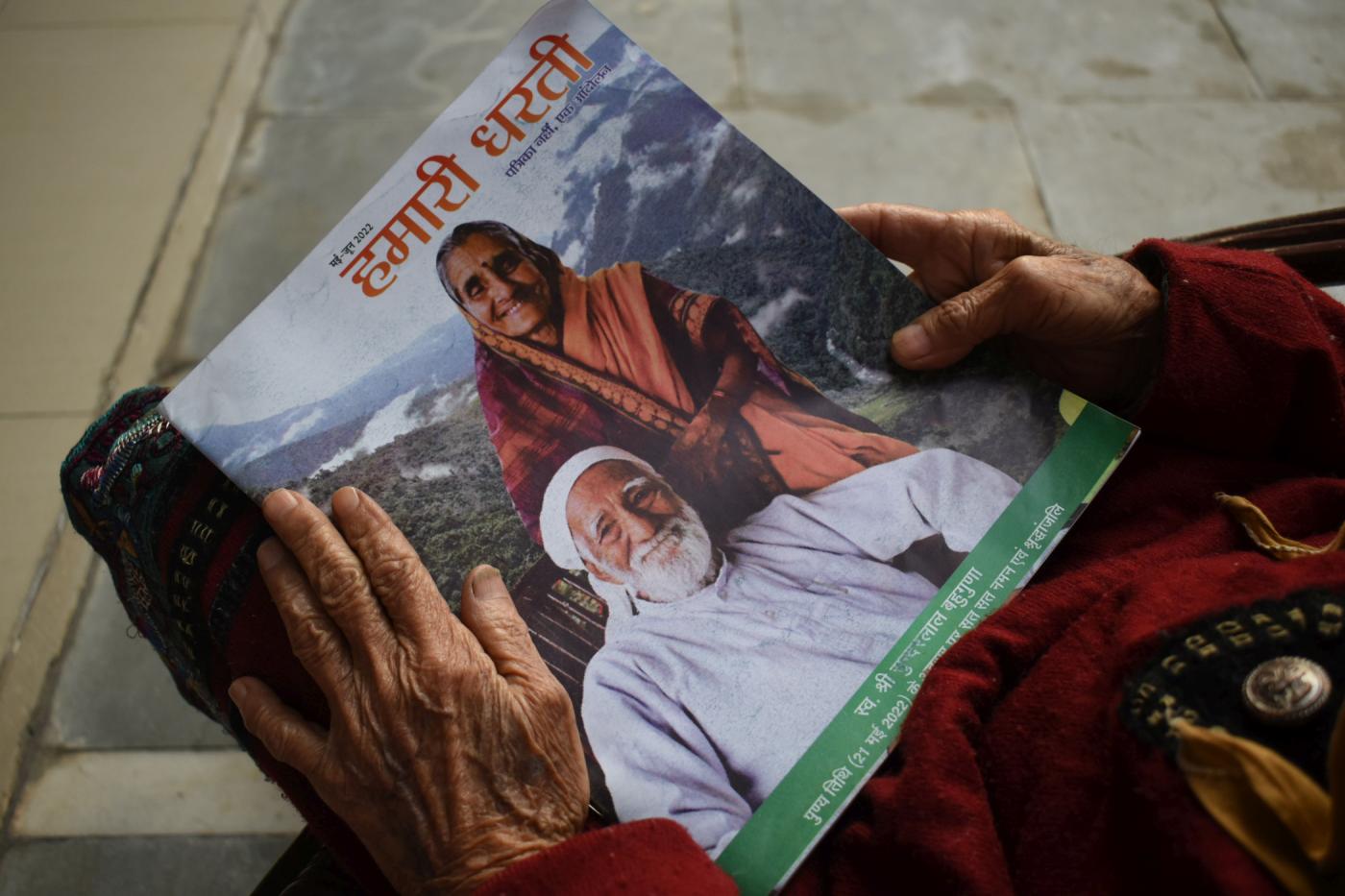

Environmentalists and one of the pioneers of the Chipko movement, the late Sunderlal Bahuguna and his partner, Vimla Bahuguna, are widely credited with coming forward with the idea of "ecology is a permanent economy”.

Taught by Sarla Behn, a senior Gandhian activist and freedom fighter, the 91-year-old Vimla Bahuguna started working as a social activist at a young age. In the late seventies, the Chipko movement was transformed into a national phenomenon after the couple put their backs into it.

In an interview with Article 14, Bahuguna spoke of living in and

empowering women in colonial India, fighting for the environment with

her husband, and why the objectives of the Chipko movement are yet to be

fulfilled.

“At this age, I’m satisfied that we did everything in our capacity to protect our environment. We dedicated our whole life to this cause and have no regrets. But I would still say that the current generation needs to do more,” she said.

Sundarlal Bahuguna was 94 years old when he died of Covid-19 in May 2021.

The Chipko movement, in the early seventies, started in the form of small and large gatherings and processions across Uttarakhand either in the aftermath of some disaster or cutting down of forests by outside labourers for outside companies.

After the Indo-Chinese war of 1962, many developmental programmes in the form of expanding road networks and tunnels began. The Himalayan region witnessed several incidents of landslides, soil erosion and floods in the decade ahead.

Then the Alaknanda flash flood in 1970 destroyed the land and people’s lives and sowed the seed of anger among students, political workers and local residents. Consequently, the villagers started coming together and organising themselves to question the state government’s policies.

Several demonstrations were held in Purola on 11 December 1972, in Uttarkashi on 12 December and in Gopeshwar on 15 December to protest outside contractors' indiscriminate logging of trees in the state.

In 1973 in Mandal village of Chamoli district where Chandi Prasad Bhatt, a Gandhian social activist, and his Dasholi Gram Swarajya Mandal—formed in 1964 in Gopeshwar to promote Vinobha Bhave's idea of non-violence and self-reliance—stopped the then Allahabad-based sports goods manufacturing company, Symonds, from felling 14 ash trees.

Local farmers used the trees to build agricultural tools, but they were not allowed to cut them down.

The same year, another protest took place in the Phata-Rampur forests, 60 km away from Gopeshwar, where the villagers again stopped the workers of Symonds from entering felling the trees.

Severely affected by the massive Alaknanda flood, the Peng Murenda forest of Raini village in Joshimath block was also marked for felling in 1974. However, the village men were not around, so the village women, led by Gaura Devi, tightly hugged the trees and did not let the workers cut any trees. This incident marked a watershed moment, and the movement gained national and global attention.

Further, in the wake of more such protests, the Uttarakhand government established a nine-member committee to investigate the causes behind deforestation in the state. After two years, it submitted its report, which ordered a 10-year ban on commercial logging in Raini and in nearly 1,200 sq km of the upper catchment of the Alaknanda.

Meanwhile, the movement continued and flourished as a working-class people's resistance against the increasing destruction of forests and their commercialisation for industrial purposes.

Sundarlal and Vimla Bahuguna had started organising people from various villages of Tehri Garhwal district to oppose trees' felling and emphasised having a cohesive conservation policy for the entire Himalayan region.

Villagers in Henwal valley protested in December 1977 to protect the Advani and Salet forests and chanted a popular slogan coined by journalist and poet Kunwar Prasun: Kya hain jungle ke upkaar, Mitti paani aur bayaar, Zinda Rehne ke Aadhar (What are the blessings of forests on us? They provide us with healthy soil, clean water and air which make life possible for us.)

In 1979, Sundarlal, Vimla Bahuguna, and five more women —Nanda Devi, Mangsiri Devi, Satyeshwari Devi, Bhuri Devi and Jupli Devi from Silyara village—spearheaded the movement and started camping inside Badiyargarh forest day and night to save it from the loggers. In the early morning of 9 January, Sundarlal Bahuguna was arrested and taken to Dehradun. However, the protest did not stop but was accelerated by the women and continued till the contractor and labourers left the forest.

There were 12 significant protests and many smaller clashes in Uttarakhand between 1972 and 1979. But the movement witnessed its most significant victory in 1980 when a request made by Bahuguna to Indian Prime Minister Indira Gandhi led to a 15-year ban on commercial felling in the Himalayas of Uttarakhand and Himachal Pradesh.

In the 1980s, when Chipko seemed to be in its last phase, Sundarlal Bahuguna embarked on a 4,800 km long foot march between 1981-83 from Kashmir to Kohima in order to create awareness about the environmental degradation of the Himalayas and preserve the ecology of the entire belt followed by cycling all the way from Gomukh to Gangasagar (origin of Ganga river to its submergence in the sea).

In the late 1980s, he, along with Vimla Bahuguna, started another struggle against the construction of one of India's tallest dam projects, the Tehri Dam Project, which continued for over a decade.

Today, Chipko is widely celebrated as a non-violent social and ecological movement across the world. However, in the past 50 years, the region has been frequently marred with many developmental disasters like the one unfolding in Joshimath town.

[[https://tribe.article-14.com/uploads/2023/03-March/01-Wed/vimla%20bahuguna.jpg]]

Could you take us back on this 50-year-long journey and tell us how the idea originated?

It was not one particular incident but a series of events and arbitrary policies by the authorities that angered the citizens. I remember in 1930, when I was a kid, people in Tiladi village of Uttarkashi district came together to revolt against the commercialization of our forests. But the then prime minister of the state sent a group of soldiers who opened fire on the peaceful protesters. They killed 17 people and later arrested most of the protesters.

The ruler managed to quell our movement then, but we never forgot. After the independence in 1968, Bahuguna ji brought out a booklet titled ‘Parvatiya vikas aur van neeti’ (Mountain Development and Forest Policy) to remind and make people aware of the incident. Then in 1974, the forest department marked ash trees for felling in the Peng Murenda forest near Raini village in Joshimath block, and we all got really disturbed. Because not only we were denied the same trees for making farm tools, and the area was badly affected by the Alaknanda flood of 1970.

So people from our village and neighbouring areas started making plans and took out processions against the order. Bahuguna ji, along with Chandi Prasad Bhatt and Ghanshayam Raturi Sailani, held meetings and visited different villages to organise people. It was in one of those meetings when our jankavi (folk singer) Sailani ji recited a poem “...Chipkapaedon par ab nakatyandya, Pahadon ki sampatti ab nalutyandya,” (hug the tree to protect them from axes, let’s preserve the true wealth of our hills). That’s how the term “Chipko” came into being. And we decided that when the contractors would come to cut down our trees, we would hug our trees with both hands.

What shaped you as a social worker?

I was born in a time and place under the dual slavery of king and queen (British rule). People in the villages were not at all happy with the oppressive regime. But the worst affected were the women, who were considered ‘useless’. I still remember when poor women often came to our house and begged for food. Those crying faces used to keep me up at night.

My brothers had dropped out of college and begun dissenting against the regime. I also wanted to do something for my people. So my brothers learned that Sarla Behan – Gandhi’s disciple – had set up an ashram in Kausani for women’s education. I got enrolled, and that was where I got the opportunity to understand and work for different issues women and men faced at the time.

In my eight years of living in the ashram, I did everything from washing clothes and utensils, rearing cattle, participating in the Sarvodaya movement, and then learning about the life and times of Mahatma Gandhi and other leaders who entirely devoted themselves to the betterment of our people.

Why were you reluctant to marry Mr Bahuguna at first?

I was in the ashram when I got a letter from my father that my wedding date had been fixed and I had to immediately leave for home. I was really shocked because I was not expecting this. Gandhi ji had said that ‘the soul of India lives in its villages’, and I wanted to work for the people living in the hinterlands of this country until they truly realise their power.

Bahuguna ji, on the other hand, was deeply interested in politics. He had left his home when he was just 13 because his family disapproved of his rebellion against the king of Tehri in the Garhwal region of Uttarakhand. So I felt our paths were different. Bahuguna ji wanted to change society through his politics, whereas I believed in staying with people in their homes and villages and working for their rights.

I showed the letter to Sarla Behan, and she asked me whether I wanted to get married. ‘I need at least a year,’ I told her. Meanwhile, Bahuguna ji had left the decision up to me. But not my father. So when I returned home, I politely refused and told my father that he should have given me some time. But my father got furious, and we argued until he asked me to leave home. I was hurt but adamant that I would not get married to Bahuguna ji unless he quit politics and joined me in social work.

Did he leave politics?

Yes, to my and everybody’s surprise, he did leave politics. After that, we both decided to move to Silyara village in the Ghansali block. This village was 22 miles away from the Tehri district. We shifted there because it was in really bad condition. People in the village had no source of income. Later, we realised that farmers could not farm on their lands because of soil erosion and the drying up of water resources, ultimately resulting from deforestation.

Bahuguna ji went to the village a few weeks before me and hired one labour who helped him construct two huts for us. Our hut later became Parvatiya Navjeevan Mandal ashram. Then I went there with my family, and we married in 1956. Our total wedding expense was 48 rupees which we equally split between us. Never in our life we took favour from anyone. We believed in doing things on our own, so we always relied on each other.

[[https://tribe.article-14.com/uploads/2023/03-March/01-Wed/vimla%20bahuguna2.jpg]]

How did women become part of the Chipko movement?

It was a years-long effort to bring women into the public sphere. When I started working in the Silyara village, my primary objective was to make women aware of their power so that they could raise their voices and speak for their rights. Although the villagers had already thrown aside the idea of education, especially for girls, because they were required to work in farmlands and help their mothers with daily chores.

But living in the same village and helping women fetch wood and water from the forest helped me win their trust. And eventually, the villagers agreed for their daughters to study after completing the chores. But that was nearly impossible. So I would wait for them to complete their household activities and teach them at night under a lantern.

During this process, women would come to us and share their daily problems. One of the issues they were really bothered by was alcohol. The entire state was marred with this problem, and people protested against the government's liquor policy in different parts of the state. But I wanted the women of Silyara to raise their voices. So after days of persuading them, they collectively started campaigning with us and eventually, alcohol was banned in most areas of Tehri district.

And this incident, or rather victory, changed how women perceived themselves. Women started realising their true worth. They understood that they were not just made for doing the household and labour work but a lot more. They could change policies. And whether you believe it or not, the way women participated in anti-liquor and other small movements prepared them for Chipko. And that’s what I wanted, for them to be mentally strong.

How did the movement evolve from saving trees to protecting ecology?

In my understanding, the women again conceived of this whole idea of protecting the forest and not just trees. When the men returned with plans to agitate and hug the trees peacefully, women realised it was not enough. Because women in the mountains share a deep connection with the forest. There is a saying in hilly regions that forests are considered a woman’s maika (maternal home). Because during those days, from woods to water, women relied on jungles for their everyday needs.

In 1974, when the women of Raini village, under Gaura Devi’s leadership, drove out the contractors and labourers who had come to cut down the trees, Chipko became a women's movement. For the first time, the women took the lead without the men.

There were times when women, carrying their kids, stayed inside the forests even at night because the contractors had planned to fell the trees after sunset, so from then on, people travelled from village to village with this idea.

However, it was not until the movement reached Henwal valley and Badyargarh that people had to struggle a lot and sat on months-long fasts to save the forest. Because from there, the entire vision of Chipko changed. One of our members—a journalist and poet—Kunwar Prasun, recited a slogan, ‘Kya hain jangal ke upkaar, mitti paani aur bayaar, zinda rehne ke aadhar’ (What are the blessings of forests on us. They provide us with healthy soil, clean water and air which make life possible for us.)

The villagers instantly picked this slogan, and all of us understood that the movement could not be just limited to saving trees, but we will have to look beyond the economic aspect of forests and work towards saving our land, air, and water sources because these are the basic premise of human existence. Since then, we have always advocated conserving the environment because that’s how we can protect the ecology.

We encounter developmental disasters like the land subsidence in Joshimath. What do you feel about the state of the environment today?

In hilly areas people have always tried to coexist with nature in hilly areas because we turn to forests for all our basic needs. But once the Britishers established control over the region, they saw the Himalayan and its biodiversity as a treasure mine. They cut down the broad-leaf trees and focused on massive plantations of commercial trees. And this continued even after independence.

We never abandoned the western development model, which stressed extracting as many resources as possible, particularly from colonies like India. Bahuguna ji and I lived near Tehri dam for 14 years to protest against the construction. I have closely seen how explosions to carve tunnels and railway lines impact the Himalayan mountains. The rapid construction and reduction of the Himalayas to a tourist place have worsened the situation. Disasters like Kedarnath and now Joshimath will not stop until we keep our environment at the centre of every growth and development plan.

Even when we were protesting and living near the dam, we ourselves installed solar panels and used biogas, to grow our own vegetables and grains. We tried to limit our dependence on market products as much as we could. Bahuguna ji, in one of his earlier essays, had already pointed out that the Himalayas had waged war against us. And so we should stop with our mindless growth plans and economic advancements. Because if we don’t, entire north India would be in grave danger.

The Chipko movement has reached its 50th year. Do you think the aim with which it had begun is fulfilled?

I don’t think so. If the goals were achieved, we would not have been discussing Joshimath. Although I do believe that people have become aware of environmental issues. Women have gained the power to raise their voices. But that number is very small. Moreover, our policymakers believe that abundance is the marker of development. And that belief has led to the unfathomable exploitation of soil, water, and air.

Today, the consumerist and tourist idea of development has defeated the main objective of Chipko, which was to grow trees that would help create more water sources and protect the environment so that the women in the hills wouldn’t have to go far to fetch woods and water.

And that is why we need more sustainable and time-sensitive initiatives by young people. Because if we hadn’t started Chipko, the mountains would have been hollow. So I feel it’s time people must get angry and raise their voices against every practice that threatens our environment.

After all these years, how do you reflect on the movement?

I feel that our fight was genuinely to protect the environment, and that’s why people from different countries could also connect with us. But importantly, people know of this movement because of the women. They recognised our struggle and contribution, which ays cherish. At this age, I am satisfied that we did everything in our capacity to protect our environment. We dedicated our whole life to this cause and have no regrets. But I would still say that the current generation needs to do more.

[[https://tribe.article-14.com/uploads/2023/03-March/01-Wed/vimla%20bahuguna3.jpg]]

How do you spend time these days?

I read a lot of books. I have always loved reading books on social and environmental issues, so I still enjoy reading Mahatma Gandhi and Vinoba Bhave’s books. I also watch television news and read newspapers.

Get exclusive access to new databases, expert analyses, weekly newsletters, book excerpts and new ideas on democracy, law and society in India. Subscribe to Article 14.

(Jyoti Thakur is an independent journalist based in Delhi. She reports on gender, environment, politics and social justice.)