New Delhi: In ten days leading to February 7, 2020, 74 Indians have been charged with sedition across five cities—and 72 across four since January 9.

The latest such cases were filed in the Uttar Pradesh town of Azamgarh on February 5, 2020, when 19 people were accused of sedition for participating in a protest against a new citizenship law. “They were saying they will snatch azadi (independence) and will get azadi anyhow,” said a statement issued by the local police.

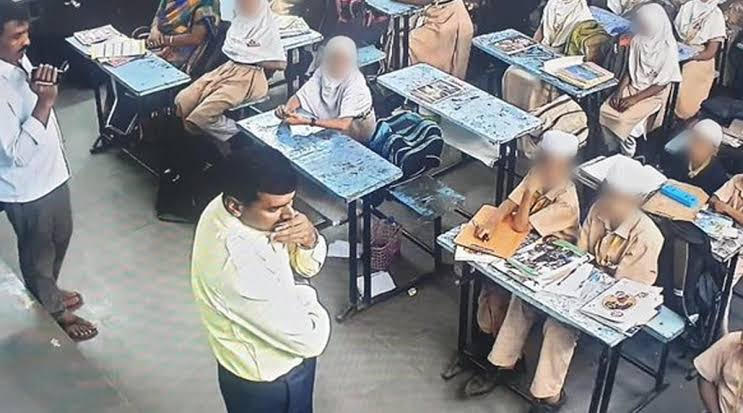

A widowed mother and a teacher in the north Karnataka town of Bidar were accused of sedition and arrested after an individual filed a police complaint, alleging that school children of the Shaheen school had abused the Prime Minister in the course of a play against the citizenship law.

“Modi is asking for our documents,” said one student in a video of the play. To that another student replies: “I will ask the person who is asking for our documents to show his document. If he doesn’t show the documents, I will beat him with slippers.”

Nearly 85 children have undergone five rounds of interrogation, and the police have seized a pair of slippers.

On February 3, the Mumbai registered sedition charges “suo moto” against 51 queer activists who shouted slogans in support of Sharjeel Imam, an Indian Institute of Technology graduate. This happened about a week after Imam was charged with sedition by police in five states for remarks he made about Assam and India.

On January 9, the police accused a student from Mysuru of sedition for holding a ‘Free Kashmir’ placard at a protest, following which the Mysore Bar Association unlawfully declared that its members would not represent her.

The Weaponisation Of Sedition Law

The allegations in all these cases do not amount to sedition under section 124A of the Indian Penal Code (IPC).

This provision is leftover from India’s colonial era and was inserted in the IPC 150 years ago, in 1870. The offence of sedition is said to be committed if any speech, performance or publication has an effect of creating disloyalty or hatred against the government.

This was, however, watered down in 1962 by the Supreme Court in the Kedar Nath case when it held that though the provision was constitutional, it cannot be invoked unless the alleged seditious act incited or had the tendency to incite violence or public disorder.

Largely used against freedom fighters, the colonial provision remained on the books despite members of the Constituent Assembly expressing their disapproval against the provision. Not only did it continue to remain in the IPC, it was further weaponised by the government by the enactment of the Unlawful Activities (Prevention) Act, 1967 (UAPA), which provides for prevention and punishment of seditious activities. It was further weaponised in 2008 by enactment of the National Investigation Agency Act (NIA Act), which made investigation of offences under UAPA subject to jurisdiction of the NIA, a central agency.

Effectively, seditious activity has been raised to the level of a federal crime.

The Role Of The Supreme Court

Though the Supreme Court watered down the law in 1962, it failed to frame any guidelines for imposition of section 124A. The Bombay High Court did so 2015 in the Aseem Trivedi case, but those guidelines apply only to Maharashtra. The Supreme Court lost an opportunity to do so in 2016 when it disposed of a petition, which had asked for guidelines, by only saying that the judgment in the Kedar Nath case should be followed by the police.

The Supreme Court’s observations will be put to test in the sedition case against Imam, who has been arrested by the Delhi Police for a speech in which he is said to have called for an economic blockade of the north-eastern states, whereas the police alleged that he had called for separation of the north-east from the rest of India. The matter is now sub-judice, and the courts will now have to decide whether the offence alleged against Sharjeel falls within section 124A.

The National Crime Record Bureau (NCRB) started maintaining data on offences against the State from 2014. That year 47 sedition cases were reported, and 58 people were arrested. In 2015, 30 cases and 73 arrests were reported, and in 2016, 35 cases and 48 arrests.

1 Conviction For Sedition? More Likely, 0

By the end of 2016, 61 cases were still being investigated, and about 33% of cases had been closed even before reaching the stage of trial. However, only one case of conviction for sedition was reported for 2014-16. This number is, however, dubious as I could find--in the course of writing my book on sedition--no judgment of conviction or any court record to support that number.

The Crime in India report for 2017 reported 51 new sedition cases but did not specify the number of people arrested that year. The report records 228 arrests, which appear to be the total from 2014 to 2017. No conviction under section 124A was reported for 2017. The report states that six trials were concluded by the end of 2017 but does not clarify whether it was for the period 2014-2017 or 2017 alone.

The latest Crime in India report, for 2018, states that 119 sedition cases from the previous years were pending investigation and 70 new cases were registered in 2018. Another case was reopened during the year. Of these, 17 cases were closed by the police, and 38 charge-sheets were filed in the year. So, 135 cases were pending investigation at the end of 2018.

In 2018, 90 sedition cases underwent trial, resulting in two convictions and 11 acquittals. Therefore, 77 sedition cases were still pending at the trial stage by the end of 2018. The 2018 report also states that 56 people were arrested for sedition during the year, of which two were convicted and 21 acquitted.

The figures for 2018, however, do not appear accurate because in Jharkhand alone thousands of people were accused of sedition for their involvement in the Pathalgarhi movement, launched to protest land-acquisition laws. Some reports state that FIRs against as many as 15,000 people were registered during the year. This is directly contradictory to the statistics reported for Jharkhand; these record that only 18 sedition cases were filed in the state in 2018. Therefore, the data provided by the NCRB is not reliable.

Sedition Used To Deter Free Speech

The reason for the sedition-data inaccuracy is that the NCRB follows the ‘Principle Offence Rule’ for classification of crime, which by its own admission could result in underreporting of the actual statistics for each head of crime recorded in its report. Under this principle only the most heinous crime (maximum punishment) is recorded for each FIR when statistics for the report are recorded.

Therefore, the number of sedition cases under section 124A IPC would be much higher than recorded, if the accompanying offences alleged in such cases are considered to be ‘major’ as compared to sedition. This has an effect on the sanctity of data pertaining to sedition cases, as both the number of cases and the number of people arrested have been inaccurately recorded.

As recent events prove, that the law against sedition is being abused to crush dissent and free-speech. The question that arises: Should be repealed? Many have argued the Indian State is not so fragile that individuals raising slogans against it would affect the integrity or sovereignty of the nation.

Section 124A falls under the chapter of offences against the State and unless the alleged offence has an impact on sovereignty or integrity of the nation, or the integrity of any state of India, it should not, the argument goes, be considered seditious. Otherwise, the only purpose the sedition law serves is to have a chilling effect on free speech.

Though the provision has been held to be constitutional by the Supreme Court, the way it is being used now is directly in contravention of the freedom of speech and expression guaranteed as a fundamental right by the Constitution.

Until the judiciary steps in to strictly enforce the judgment in Kedar Nath and other subsequent judgments, which further emphasize the benign nature of the sedition law, citizens will remain at the mercy of the State.

(Chitranshul Sinha is an advocate on record of the Supreme Court of India and the author of a 2019 book, The Great Repression: The Story of Sedition in India)