Ghaziabad, Uttar Pradesh: In 2017, five students from a government school in Kaithal, just over 100 km south of Chandigarh—the joint capital of Haryana and Punjab—filed a petition against the Haryana government, demanding a teacher, a toilet and clean water.

What should have been an indictment of Haryana’s education system was met with resignation. “This is just the way things are,” said M*, a government school teacher in Nuh district, which borders Gurugram, part of the National Capital Territory, to the south.

Despite repeated claims by Haryana’s education minister Seema Trikha that the state’s education system has improved significantly since 2014, Haryana has consistently slashed its education budget—from 17.3% of its total budget in 2010-11 to just 13.8% today.

In November 2023, the director of secondary education, Ashima Brar, filed an affidavit at the Punjab and Haryana High Court revealing that over Rs 14,500 crore in union and state education funds was unutilised over the last decade.

The affidavit identified infrastructure gaps: 1,047 schools lacked toilets for boys, 538 schools lacked toilets for girls, and more than 8,240 schools were still awaiting funds for classrooms.

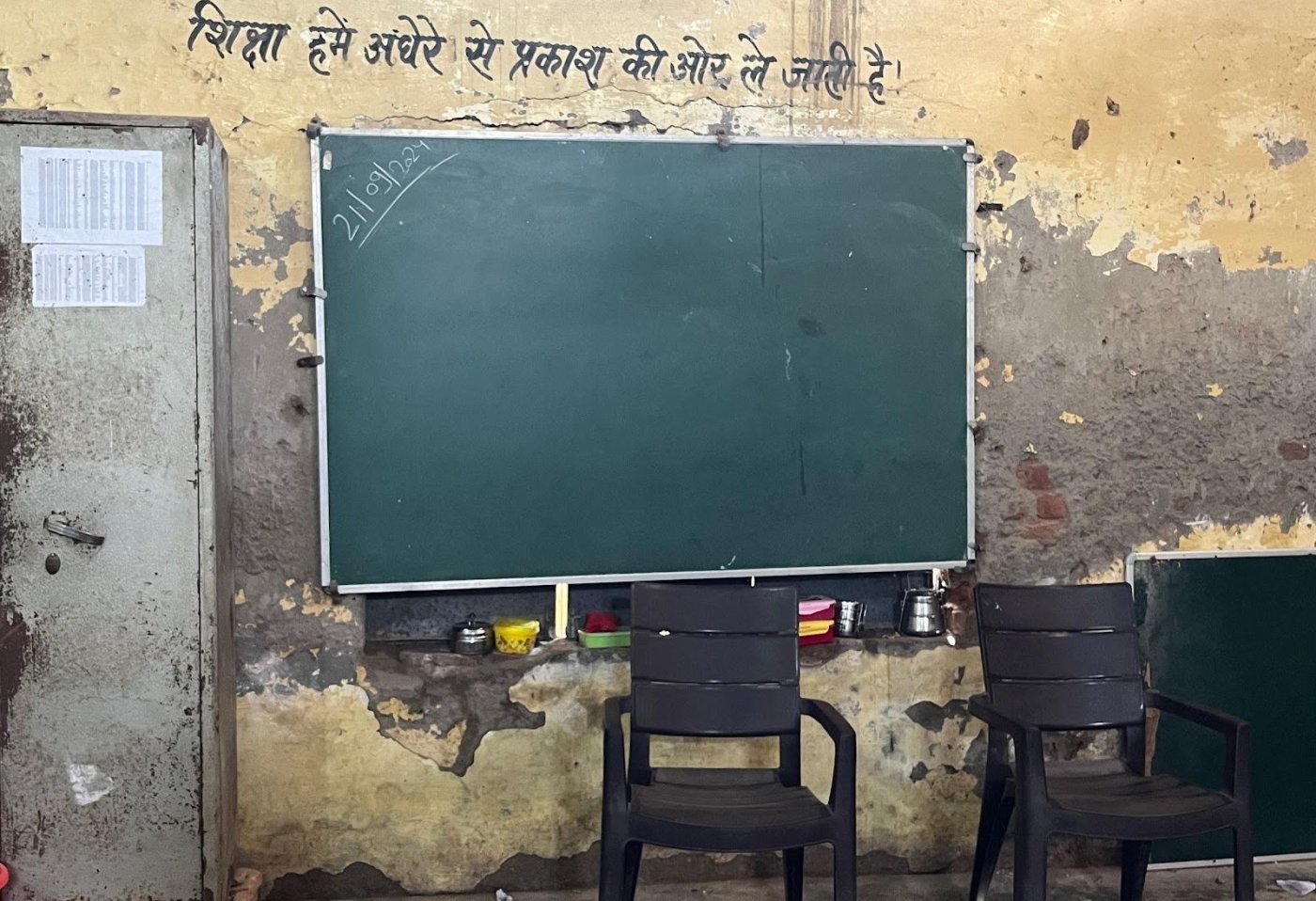

In the village of Shamsabad Khechatan, less than 100 km south of Delhi’s international airport, in the Nuh district of Haryana, a classroom is just a memory. The government school building was demolished by the department of school education Haryana—two decades ago.

Since then, the government primary school exists only on paper. The building is gone, but the students remain.

Funds are sanctioned and teachers are appointed, yet the ‘school’ functions out of a rented, half-constructed shed, for which the teachers paid Rs 12,000.

All five classes of the primary school are crammed together in a single makeshift shed. There are no toilets or access to drinking water. The teachers buy 20-litre water bottles each week for students to drink as well as to cook the mid-day meal.

The school does not receive gas cylinders for cooking, so the mid-day meal is cooked on a wood-burning stove made of mud, in the open, exposed to the elements. On rainy days the teachers scramble to find a gas stove and cylinder in order to feed the children.

The primary school students are forced to use an empty plot nearby as their toilet. Yet, official records show the school has functional toilets.

Two small, unfinished structures stand at the entrance, sealed, without water connections or even toilet bowls.

“These,” said A*, a teacher at the primary school, who asked not to be named, said, “are what show up as functional toilets on the portal.”

An Aspirational District

Haryana’s Nuh district is a part of the Aspirational Districts Programme, launched in 2018 by Prime Minister Narendra Modi to improve infrastructure and boost the economy of 112 of India’s most underdeveloped districts across key performance indicators.

The programme aims to leverage each district's strengths and track progress across five socio-economic areas, including education and health.

The ultimate goal of the programme is to “first catch up with the best district within their state, and subsequently aspire to become one of the best in the country”, as a part of the central government's plan of “raising the living standards of its citizens and ensuring inclusive growth for all”.

During the September 2023 Sankalp Saptah (Resolution Week), Modi praised the programme for improving the lives of over 250 million people, highlighting improved quality of life and governance.

He also emphasised his close monitoring of the program's progress, saying, “When I used to regularly check the progress of the Aspirational Districts, it brought me so much joy.”

According to the Champions of Change dashboard, Nuh ranked second in education in November 2022 but dropped to 14 by June 2024.

Despite the dashboard stating that 100% of schools in Nuh had functional toilets and drinking water and an August 2024 written reply in Rajya Sabha that reported an allocation of Rs 18.3 crore to Nuh under this programme, none of the five schools that Article 14 visited had classrooms, toilets, or clean drinking water.

In November 2023, the Haryana government acknowledged, in an affidavit to the Punjab and Haryana High Court that it needed Rs 1,784 crore to repair the infrastructure of its schools.

It only allocated Rs 424 crore—24% of what was required.

Around 63% of schools need funds for classrooms and boundary walls, according to the state’s admission. The Punjab and Haryana High Court fined the Haryana government Rs 500,000 for the state of its school infrastructure.

In response to the students’ petition, additional affidavits were filed by Jitender Kumar, Director, Secondary Education and R S Dhillon, director general, elementary education, on 6 August 2024, claiming that “all basic amenities”, such as “electricity, functional toilets for both boys and girls and drinking waters (sic) are available in each and every school”.

None of this is in evidence.

At the government school in Gohana village, Nuh, teachers said they personally paid Rs 1,500 weekly to hire private tankers for water.

"There are posters of Jal Jeevan Mission on the wall, but the school isn’t connected to any water pipeline," said M*, a middle school teacher.

Even more prosperous schools in Nuh District, like the Government Senior Secondary School in Fatehpur Namak—designated to become a PM Shri school, intended to showcase the implementation of the National Education Policy 2020, in the academic session starting March 2025—had fundamental issues.

The primary wing had only nine teachers for its 1,200 students.

According to right to education guidelines, this school should have 40 teachers to meet the required student-teacher ratio of 30 to one.

Moreover, the school’s water tank was also donated by villagers, and despite the school's upcoming management under the PM Shri scheme, there remains no water connection provided through the Jal Jeevan Mission.

Article 14 sought comments over email from the statistics and monitoring division of Haryana’s education department on 23 September 2024. There was no reply. We will update this story if they do.

Crumbling Buildings, Overcrowded Classrooms

“I will be suspended one way or the other—either when this roof collapses and injures a child, or for speaking to you about it,” said S*, a teacher at Government school at Punhana, in Nuh district.

The ceiling fan creaked precariously, the walls were damp, and a room meant for storing mid-day meal rations was the staff room.

“This is what it is,” said S, while gesturing. “A storage room doubling as a staff room. No place for teachers to sit, no proper classrooms—no dignity in our work.”

Run by the municipal corporation, the government school in Punhana was once a small primary school, later expanded to include a middle school.

Today, it is the only primary and middle school in the area. For the families of Punhana, this school is their children's only shot at an education.

S sat patiently as students came by, some sitting in his chair, others chatting about their day or sharing complaints about classmates. As he played with a six-year-old tugging at his chair, he explained the school’s situation.

“We have about 450 students here in the primary wing and 210 students in the middle school,” he said, “but the middle school has no classroom.”

The school once had five rooms. After portions of the roof collapsed, the teachers wrote multiple letters, in 2022, to the chairman of the municipal corporation in Punhana, Balraj Singh.

“One day, after a close call, I confronted him in person,” said S. “I told him our lives were in danger, and if they didn’t act, I’d hold them responsible for any deaths.”

The education department demolished three unsafe classrooms in 2023 but has not replaced them, leaving the middle school with no rooms for classes.

“It’s been a year, and we’re still waiting for construction funds,” S said. “We now have to run classes by loaning space from a nearby municipal hall that houses an Anganwadi centre.”

S said that he makes children sit facing different directions in the same room to create the illusion of separate classes, as 88 students sit in a small section of the anganwadi (a creche) in suffocating heat.

On October 10, 2023, former education minister Kanwar Pal Gujjar posted on X, celebrating village heads from Punhana thanking him for upgrading a local school.

"Claims for my school have been pending for years," said S. "No one even bothers to visit and see the condition of schools here in the city."

But the lack of classrooms isn’t the only pressing issue. The remaining building is still dangerous, with parts of the roof collapsing regularly.

“I was teaching one day when a chunk of the roof fell just inches away from me,” recalled I*, a teacher who has been with the school since 2006. She, too, asked not to be named. “I could’ve been seriously hurt, but I had just stepped away to write on the blackboard.”

No Working Toilets, Drinking Water

I said she witnessed first-hand the growing neglect of her school.

“When it rains, the sewage water floods the entire school, rising up to our waists,” said I. “We have no choice but to send the children home. If something happens to a student, who will be held responsible?”

The middle school has no functioning toilets, and the four toilets in the primary wing serve all 660 students.

The school didn’t have water supply until 2020. But the water quality remains poor and unchecked.

“They built a tank but left a hole in it on the roof. Rainwater, dust, and everyday pollution contaminate it,” said S. “It breaks my heart to see the children drinking unsafe water, but we have no other option.”

The middle school was registered to serve as a polling booth in the October 2024 assembly elections.

“We were required to fill out a form certifying that the polling booth has proper infrastructure,” said S. “I truthfully said that we have no toilets, but officials pressured me to lie, to say we have them.”

“Look around,” said S as he gestured to the empty space. “There isn’t even a building left—where would the toilets come from?”

Balraj Singh, chairman of the Punhana municipal corporation claimed he had not received any official communication about the state of the school. Singh acknowledged being aware of the middle school’s situation but denied pressuring the school to provide false information.

“The only information I have is about the middle school building, which we had to demolish due to its poor condition,” said Singh. “However, we haven’t been able to issue a tender for reconstruction because of the Lok Sabha and Vidhan Sabha elections. This delay is out of our hands.”

The deteriorating conditions of the schools cast serious doubt on the affidavits, submitted to the Punjab and Haryana High Court by Jitender Kumar, director of secondary education, and R S Dhillon, director general of elementary education, which said all schools in Haryana were fully equipped with “basic amenities”.

These claims stand in stark contrast to admissions by government officials, who acknowledge their inability to provide adequate classrooms and bathrooms, raising concerns about the accuracy of the government's assurances.

This assertion in the affidavit is part of a series of affidavits presented by the state government to the Punjab and Haryana High Court, which echo these claims. The Aspirational Districts Programme dashboard reflects these claims.

"The basic amenities in schools, as claimed in the Education Department’s affidavits, exist only on paper,” said advocate Pradeep Kumar Rapria, who is representing the student petitioners. “Even the posts of sweepers remain vacant, which undermines the government’s Swachh Bharat Mission."

No Future For Students

In 2022, the Haryana government launched Mission Buniyaad, a programme to nurture talent and provide free coaching for prestigious exams like JEE and NEET.

“Three girls from our school were chosen for this training,” S said. “They have so much potential. But without classrooms, without resources, how will that potential ever be realised?”

While the school S teaches at, in Punhana, has fewer classrooms than it should, the school in Shamsabad Khechatan has moved from one half-constructed building to another, with villagers offering their homes for rent.

The teachers pay rent from their own money.

“We have written multiple letters to the district collector. One day last year an official also came and clicked pictures,” said A. “Neither did any support for rent come, nor did anything change.”

In just the past year, the school has moved four times.

Many parents, tired of the constant relocation, have pulled their children out, but there are no other options, as private schools in the city are far too expensive for them.

A said, “The children who leave, often never return to any form of education.”

The temporary shed, with the only roof in the school, is the last hope of education for children in Nuh’s Shamsabad Khechatan village.

B*, a mid-day meal worker, whose two children were enrolled in the school, said, "If my children don’t study here I’ll have to face the harsh reality—that they’ll never be better than me in life."

*Identities hidden on request.

(Shubhangi Derhgawen is a freelance journalist based in Delhi, specialising in welfare, and environmental issues.)

Get exclusive access to new databases, expert analyses, weekly newsletters, book excerpts and new ideas on democracy, law and society in India. Subscribe to Article 14.