Bengaluru: Nearly four years into Q’s incarceration for alleged terrorism, his determination had worn down.

Q, a Muslim resident of Karnataka, who spoke on the condition of anonymity, was accused of recruiting local Muslims to wage war against the Indian state. The state police claimed to have arrested them while they were plotting a terror attack in Bengaluru.

Article 14 met Q, who was out on bail, in a hotel in a dusty small town in Karnataka.

All details have been anonymised on his request.

In a crowded state prison, he found others like him. Some had been in prison on terror charges for over a decade without bail and without their trials gathering speed.

He said bail had been denied several times, and he had stopped applying for it. The court had examined barely half the witnesses. “The investigating officers kept telling us it’ll take years for this case to conclude,” he said. “They’d tell us that the jail would be our home.”

One day, he came across a news article. A terror accused lodged in a prison far away had pleaded guilty. The accused received a reduced sentence, and his release was imminent.

This set in motion a train of thought.

“We heard about the option to plead guilty. It didn’t take us long at all to be convinced of it. We wanted to go home,” said Q.

Negotiations over sentencing started with the National Investigative Agency (NIA).

The NIA were more than keen on the guilty plea, said Q.

The deal was accepted. The judge held the accused guilty of terrorism. They received reduced sentences, most of which they had already served as undertrials.

“We held hands, formed a circle and just hugged each other. Tears flowed copiously. Happy tears. It felt like a festival. It felt like a happy day,” he said.

Q paused and let out a laugh.

“I still remember the faces of the other inmates. They were shocked. They have never seen someone so happy after being found guilty.”

80% Of The People Convicted Under UAPA In Karnataka From Guilty Pleas

The third of this four-part series on the use of UAPA in Karnataka from January 2005 to February 2025, based on research by the School of Oriental and African Studies (SOAS) University of London, reveals that forced guilty pleas play a significant role in securing convictions.

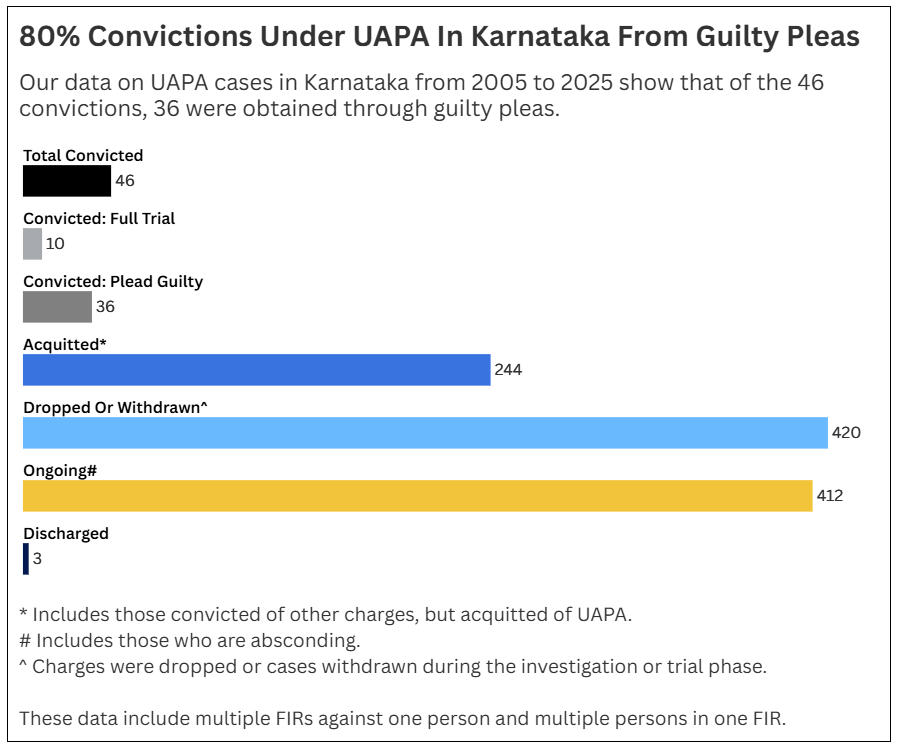

Q is among the 925 persons accused under the UAPA law in Karnataka from January 2005 to February 2025, and one of the 46 convicted till February 2025.

Of the 46 convicted, 36 (nearly 80%) had pleaded guilty before the judge during the legal proceedings.

The NIA was involved in 29 of these convictions.

All 29 of these convictions in Karnataka resulted from the accused pleading guilty during the trial, rather than from a full trial process with detailed scrutiny of the evidence.

The NIA claims to have a 92.31% conviction rate in cases filed under several laws, including the UAPA.

In the first part of the series, we reported on the types of incidents that led to 46 convictions in Karnataka over twenty years.

Weaponisation Of UAPA Against Muslims

The first of the series on the use of UAPA in Karnataka also revealed a stark bias in the application of the law by the BJP against Muslims.

In the first part, we reported that eight in ten persons were accused under the UAPA during the BJP’s tenure. In other words, the BJP invoked the law 5.2 times more than the Congress Party in Karnataka over the past twenty years.

Karnataka has experienced nearly equal periods of rule by the Indian National Congress (9.09 years) and the BJP (10.5 years), as well as a period of President’s Rule of 226 days. The Janata Dal (Secular) was in coalition with both parties intermittently over the past 20 years.

Of the 925, 783 (84.6%) were Muslim.

Part 1 also reported a disparity between convictions and acquittals, with convictions occurring 5 times less often than acquittals.

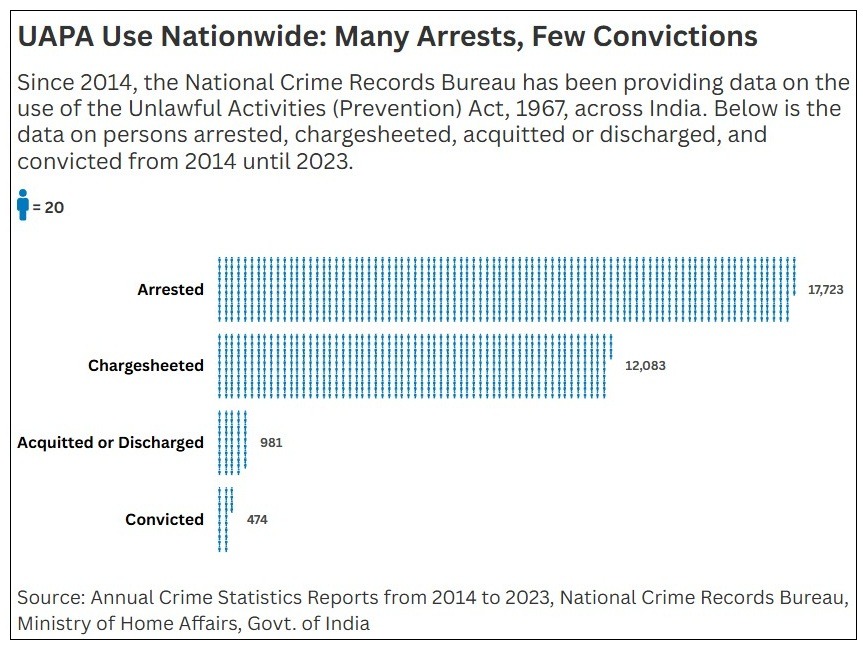

Only 28% of concluded trials across the country between 2014 and 2022 have led to convictions, according to the home ministry.

The figure is even worse when viewed in the context of all convictions reported across India by the National Crime Records Bureau (NCRB), as we revealed in Part 1 of this series.

As our examination of convictions under UAPA in Karnataka and across India reveals, convictions do not occur solely because a judge found guilt beyond a reasonable doubt after a rigorous trial. They are obtained by forcing the accused to plead guilty.

NIA Forced Pleas of Guilt in UAPA

Our data beyond Karnataka covers 62 NIA cases in which 489 persons were accused under the UAPA across India. These cases were concluded between 2012 and February 2025. Court orders were obtained from the NIA website and the E-Courts portal. (For a more detailed explanation of the method and limitations of data collection and digitisation of judicial records, see the first of this series.)

261 persons were convicted across these 62 cases.

Of these, nearly 115 persons, or over 40% of the convictions under UAPA, had pleaded guilty, as documented in court orders.

75 of those who pleaded guilty were accused of conspiracy or association with proscribed terror groups, but not of violence.

That is, where arrests were based on police surveillance of suspects, evidence gathered in their online chats, informers or raids that reportedly led to seizure of weapons, fake currency or arms. (In Parts 1 and 2 of the series, we detailed how cases of conspiracy are made under the UAPA.)

The law (section 229 of the CrPC and section 252 of the Bharatiya Nagarik Suraksha Sanhita) allows the accused to plead guilty at any stage of the trial, from the time of framing of charges until the time a verdict of guilt or innocence is pronounced.

Only three of the 115 persons had pleaded guilty when the court framed charges (a process at the initial stages of the trial where the court reads out the charges against the accused).

The remaining 112 persons pleaded “not guilty”, at the time charges were being framed, but like Q, all 112 pleaded guilty four to five years into their trial.

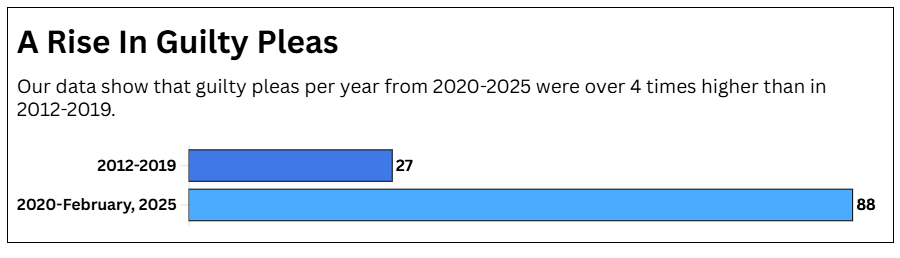

In fact, in the years since Q’s decision, the phenomenon of pleading guilty under pressure from the NIA had gathered steam.

After 2020, our data show that nearly two-thirds of convictions involved defendants who were forced to plead guilty.

That is, between 2012 and 2019, 27 persons pleaded guilty.

This number increased between 2020 and 2025, during which 88 individuals pleaded guilty.

Guilty pleas per year from 2020 to 2025 were over four times higher than in 2012 to 2019.

“It is using the legal system as a way to blackmail. Guilt or innocence doesn’t seem to matter,” said Mayur Suresh, reader in law at SOAS and the principal investigator on the UAPA research.

“And this is happening because bail is repeatedly denied in UAPA cases,” said Suresh.

Our data on the NIA’s strategy to force people accused under UAPA to plead guilty, mirrors a recent multi-part series by the Forced Guilt Project.

Why Do They Plead Guilty?

When I met Q, he maintained his innocence of the allegations of terror against him.

Specifics of his case are being withheld on his request, as he feared further scrutiny from authorities.

This caution was a routine occurrence during the months of fieldwork spent interviewing those charged under the UAPA.

The application he filed upon pleading guilty acknowledged his “repentance” for his “misguided actions”.

In court, the judge repeatedly asked him, as is the procedure, whether the plea was voluntary and whether he understood the consequences of his actions.

Q then replied in the affirmative.

His words are repeated in almost all pleas of guilt submitted before courts across the country.

Similar words emerge in the orders recording a plea of guilt for 115 people, namely, “repentance”, “misguided actions” and “an eager desire to reform and join mainstream society”.

“These are the things you have to write. It’s like a standard form,” said Q.

When he first entered the prison, Q was filled with anger.

“I wanted to challenge every accusation. I wanted to win and prove my innocence to the world. I even studied law in prison to help my case,” he said.

The loneliness of prison chipped at him.

His family were held in their own confinement: ostracised by relatives, neighbours and even the broader Muslim community. His brother and father lost their jobs for being associated with him, a “terrorist”.

“When I’d hear this, I’d think: If I were at home, I could do something to help them,” said Q. “But in jail, I was useless.”

This thought gnawed at him relentlessly.

When the opportunity to plead guilty came, he didn’t hesitate.

His family expressed shock, then a strong objection. His own lawyer objected. Then came visits and pressure from civil society organisations, who believed that this action would smear the Muslim community.

“No one will understand what it’s like to be confined without an end date,” said Q. “Once we were sentenced, we had an end date. It was like a weight had been lifted, and we just had to endure a few days to be back home with our family.”

A System Designed To Coerce A Guilty Plea

Around the time of Q’s release, R, a Muslim resident of Karnataka, entered a prison many miles away.

R had been picked up from his home, and the seemingly endless series of interrogations went by in a blur.

He was arrested under the UAPA as part of a massive crackdown on a “pan-national conspiracy” to raise funds and propagate radical Islamic ideology. R claimed he was arrested for merely speaking to a person at a public meeting. Unknown to him, he said, the person had been under the NIA scanner as a recruiting agent for the terror group.

R, a soft-spoken man, had grown up in a middle-class home in the city, far removed from the harsh isolation of a prison. He expected prison to be a soul-shattering prospect, where he would be treated like a terrorist.

Instead, in a dingy cell of this large prison, he found a tinge of envy. “Many inmates told me that I was lucky to be booked under UAPA. They said I just have to wait a few years and then strike a deal with the NIA,” he said in 2024.

In R’s case, four years after his arrest, no charges had been filed. The chargesheet listed over 300 witnesses. “We’d go for a hearing, and the next date would be 2.5 months later. Little by little, it destroys your hope,” said R.

He had initially resolved to fight. He had everything to lose: he was from a locally prominent family, had a successful career, and young children who adored him.

“The law is designed to keep you in jail for as long as possible. We’d see the judge listen intently only to the public prosecutor,” said R. “Even on days that our lawyers would make a good defence point, the public prosecutor would merely say, 'This is a matter of national security’, and we could see the judge nodding his head.”

“It takes time for the reality of the case to sink in. You really start to think about pleading guilty. The system is designed for that.”

R claimed that the investigating officer in the case had encouraged them to plead guilty. The promise was that if they did so, the NIA prosecutor would agree to a reduced prison sentence. He could even be home within the year.

“It was a big risk. We had only the word of the investigating officer. What if we got 14 years or a life term? We had no guarantees. But it presented a flicker of hope. It was more hope than what I had at the time,” he said.

In his initial plea, he stated that he explicitly pleaded guilty because the trial was slow.

“The judge rejected this. The only plea that was accepted was where we say that we are guilty of our crimes and we are remorseful of our actions,” he said.

R and Q are right, that in court orders, the forced nature of the guilty plea is not mentioned.

Instead, judges say that “This Court needs to take into account the positive aspect of their act of pleading guilty,” as a special NIA Court in Bengaluru recorded. Or an order from the Special NIA Court in Mumbai that says, “Their (the accused) repentance appears to be genuine and enshrined within a ray of hope of joining the mainstream of society to lead a normal life.”

Radhika Chitkara, an assistant professor (law) at NLSIU, Bengaluru, whose research specialises in the use of the UAPA, said, “For the NIA, their pressure tactics yield results. Pleading guilty helps them show high conviction rates. While, for judges, who are supposed to scrutinise these, accepting a plea of guilt can help them show a higher disposal rate,” said Chitkara. “All of these negotiations are happening in the shadow of the law.”

A Game of Chance

In many cases, we found that the accused pleaded guilty a few days after their bail or discharge application was rejected or dismissed (an application to the judge seeking dismissal on the grounds that there was insufficient evidence to proceed to trial).

Take the case of the men from Uttar Pradesh arrested in Mumbai in 2016 for “trying to radicalise Muslim youth to join Islamic State (IS)”. Two of the accused pleaded guilty in 2022, six years into their trial.

In their bail application, filed a few days before their guilty plea, they note that only 30 of the 228 witnesses mentioned in the chargesheet had been examined by the prosecution.

In their analysis of NIA’s conviction rates for 2024, People’s Union for Democratic Rights (PUDR) said the delays in trials for UAPA were not just an injustice, but also allowed for this “cynical practice of ‘guilty plea’”. The report notes that “while the accused may have a right to plead guilty, the practice is not appropriate as cases of terrorism and national security must not turn on factors other than proper investigations and fair and just trial procedures.”

In Q and R’s case, the decision paid off.

But it is a gamble, as three persons accused in the 2018 Bodh Gaya Temple blast case in Bihar found out.

Nearly three years into the trial, no witness had been examined by the prosecution. They chose to plead guilty instead. It was accepted, and a judgment was delivered the same day.

To their shock, they were handed imprisonment for life for waging war against the Indian state under Section 121 of the IPC. The accused appealed to the High Court, which observed that there was a “miscarriage of justice” because the court had not given sufficient time for the convicts to understand the consequences of their guilty pleas.

Six months later, the Special court for NIA cases in Patna issued a modified judgment: this time, removing charges under Section 121 of the IPC and sentencing them to a maximum of seven years in prison, or nearly the time they had already spent as undertrials.

The Afterlife

It’s been years since Q and R were released from prison as convicts. They harbour no regrets for pleading guilty.

“Assume I waited in prison for three or five years or longer. Assume I’m acquitted. Does it really matter? What kind of employment am I going to get, whether I’m guilty of a terror case or I’ve been acquitted of it?” said R.

He was sentenced to five years in prison after serving four years as an undertrial.

“I felt no happiness or sadness. Just relief.”

R came back to a shattered home: divorce, unemployment, isolation and debt. His mental health spiralled. He eventually found a job with a small firm, the sort that lacks processes for criminal background checks.

R has the luxury of the big city, where he found anonymity amid the indifference of densely packed neighbourhoods. Surveillance by investigating agencies, however, has become a part of his life.

“Once you are put in the state’s database, you’ll always be stuck there even if you’re acquitted or convicted,” said Q. “I don't regret pleading guilty. In fact, each time I read about a terror case where they have been convicted after a decade in prison, I feel assured in my decision.

“At least I came out as soon as I could and have been with my family since,” he said.

Third of a four-part series. Read Part I here, Part II here and Part IV here.

Names of those interviewed have been withheld on request.

Credits:

Investigative reportage, data mining, research & analysis for Karnataka, Mohit Rao; All India data mining and analysis, Sakshi R., Nikita B; Research on acquittals in UAPA in Karnataka, Zeba Sikora; Background research, Vibha S.; Research Direction, Lubhyathi Rangarajan; Principal Investigator, UAPA Data Series, Mayur Suresh; Edited by: Betwa Sharma.

This data is produced by a research project at SOAS, University of London, funded by the British Academy and the Leverhulme Trust

Get exclusive access to new databases, expert analyses, weekly newsletters, book excerpts and new ideas on democracy, law and society in India. Subscribe to Article 14.