Kupwara (Jammu & Kashmir): Abdul Rashid Dar, 33, had had a few bites of his dinner on a freezing December night when his family heard a loud banging on their door at 8:15 pm.

It was 15 December 2022, and Rashid’s elder brother, Shabir Ahmad, went to see who it was. As soon as he opened the door, he was faced, he said, with a squad of soldiers.

“Rashid kahan hai (Where is Rashid)?” the soldiers asked, according to Shabir, a special police officer (SPO) with the Jammu and Kashmir (J&K) police.

Rashid’s eldest sister, Mehfooza, said she rushed to the kitchen where he was having dinner and told him the army was looking for him.

“He said, ‘Don’t worry, I will see what the issue is,” said Mehfooza.

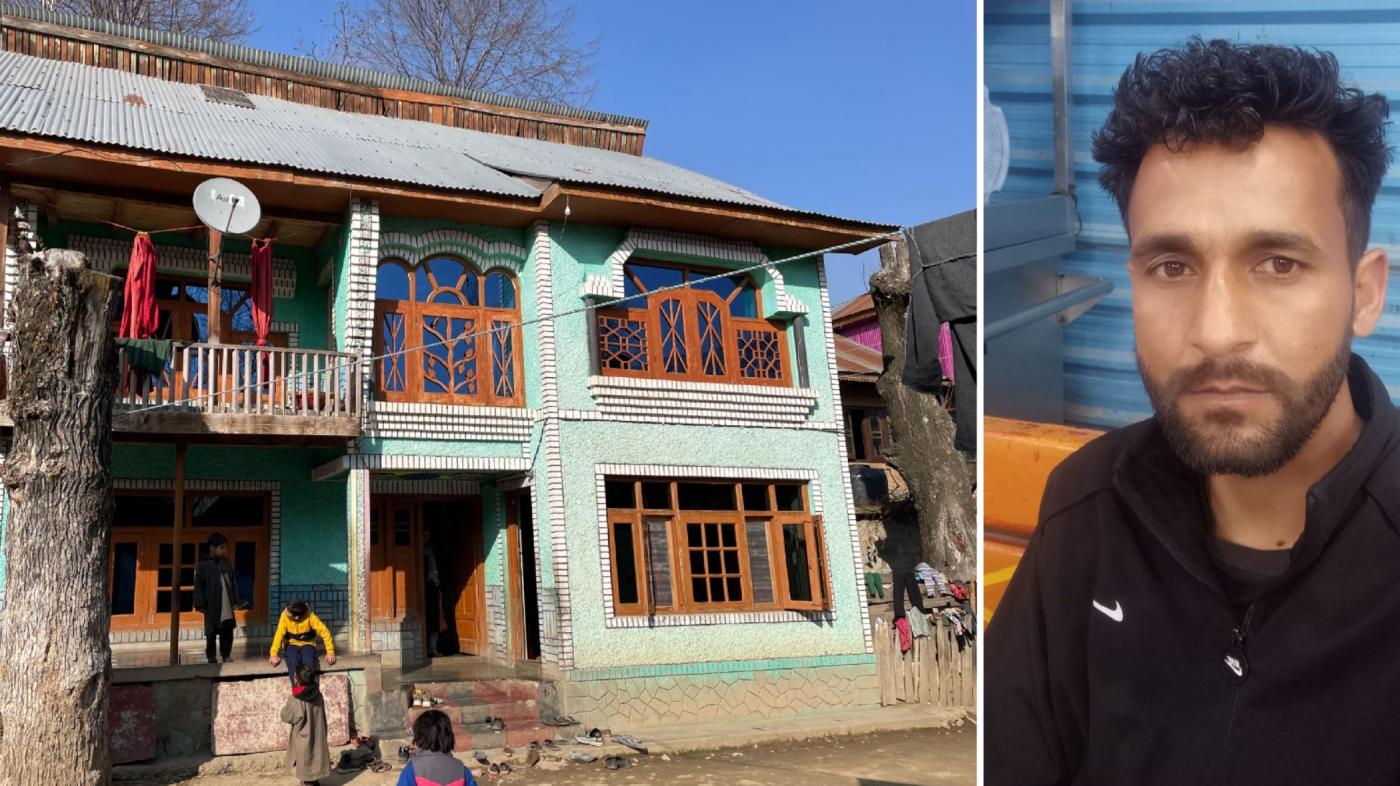

The Dar family lives in a two-storied house without fencing in a village called Kunan nestled between pine trees and paddy fields in the district of Kupwara bordering Pakistan, 85 km northwest of Srinagar, the capital of the union territory of J&K.

Kupwara is flooded with soldiers, army camps and other signs of militarisation. A number of villages lie next to the line of control, the de facto border with Pakistan. Most militants from Pakistan infiltrate Kashmir from these villages, according to security forces.

Like the other 21 districts in J&K, Kupwara has been a “disturbed area” for 32 years since 1992, allowing the army sweeping powers to detain or shoot at those associated with militancy.

As soon as Rashid stepped out of the house, soldiers surrounded him and barged in. Mehfooza said she suspected something was wrong when soldiers snatched his mobile.

By this time, all of the family of eight, some who stayed there and others who were visiting, were outside the house, pleading with the soldiers to tell them if Rashid had done anything wrong.

Rashid, a 10th-standard dropout, described by his family as a calm, self-effacing man, is the main wage earner of his proximate family of three (parents and a single sister), driving a goods minivan, hiring out tents or selling shawls with one of his two brothers, both of whom live separately with their families.

Another brother became a militant in the 1990s and was shot dead in a firefight.

“He would mind his own business,” said Hilal Ahmad Dar, Rashid’s elder brother with whom he would travel to Punjab or Delhi selling shawls.

Rashid’s father is bed-ridden from a stroke and suffers prostate issues and diabetes.

“The town commander (a major or company commander) kept saying that they only needed him (Rashid) for an inquiry and that they would release him the next day,” said Rashid’s mother, Khera Begum, 65, who was tense and apprehensive and consoled by relatives and friends when we met her.

“The town commander kept his hand on my head and assured me that my son would be released the next day,” said Khera Begum, who requested the soldier not to beat her son since he had had two ear surgeries. “Tame woun mae aames karni kahe touch (He told me, ‘no one will touch your son.’)”

'We Were Told He Would Be Released The Next Day'

With night temperatures at —3.6 deg C in Kupwara, the family pleaded with the soldiers to allow Rashid, who was clad only in thermal underclothes and a hoodie, to wear warm clothes and shoes, but he was not allowed to, according to Mehfooza.

“He wore his father's shoes and a trouser on the lawn and was bundled in an Army vehicle and taken away,” said Mehfooza. “We were told that he will be released the next day.”

That was the last the Dar family ever saw Rashid, his disappearance the latest of more than 8,000 over 32 years of J&K’s insurgency.

From the accounts of Rashid’s family, the local police and sarpanch or headman and the interpretation of India’s law for “disturbed areas” by two retired generals we spoke to, it appeared that the soldiers who arrested Rashid did not follow the procedures they were required to under the law and the army’s own procedures.

On 31 October 2019, when J&K became a union territory, the government of Prime Minister Narendra Modi discarded hundreds of laws that applied to the former state alone, but among the handful of laws it retained was the AFSPA.

Article 14 sought comment on Rashid’s disappearance and the apparent violations of the law by the army from Col Emron Musavi, public relations officer (defence), Srinagar.

Col Musavi said that the “issue is being pursued and the army is assisting the Police in tracing the missing individual”. He declined further comment.

National Conference leader and member of Parliament, Hasnain Masoodi told Article 14 that he discussed Rashid's disappearance with union defence minister Rajnath Singh on 23 December and sought his intervention."The defence minister gave a patient hearing and assured me that he would look into the matter," said Masoodi.

Meenakshi Ganguly, South Asia director for Human Rights Watch (HRW), a global human-rights advocacy, said the army was primarily responsible for Rashid’s disappearance.

“The army cannot shrug off responsibility by saying a suspect fled,” said Ganguly. “And considering numerous accounts of torture and unlawful deaths by the military, it crucial that there is an independent investigation.”

[[https://tribe.article-14.com/uploads/2023/01-January/06-Fri/Abdul%20Rashi%20Dar.jpg]]

How The Law Was Violated

Rashid’s brother Shabir told Article 14 that he asked the “town commander”, the major heading the army unit that detained his brother, if he had informed the local police about the raid on their home and his brother’s detention.

The major, according to the family, said he had informed the police of Rashid’s detention over the telephone.

Indian law requires that the local police either accompany the army or that the army inform the police when anyone is detained in the manner Rashid was in a “disturbed area”, where the army has special powers to detain or shoot people.

However, a senior official—speaking on condition of anonymity because he was not authorised to talk to the media—of the Kupwara police told Article 14 that it was Rashid’s family that informed the police of his detention.

Khursheed Ahmad Dar, the sarpanch or head man of Kunan village, confirmed to Article 14 that the police were not with the Army when Dar was detained.

“He (Dar) was detained in front of me,” said Khursheed. “We asked them (the army) whether they had informed the police. They (the army) said we don’t need to.”

While Dar was being detained by one army unit, another searched his sister’s house in the same village.

“The army was looking for my brother in my sister’s house, but since he was at his own house, they came here,” said Mehfooza, Rashid’s sister. “The sarpanch of our village was with them, and my brother was detained in front of him.”

Former northern army commander Lieutenant General DS Hooda (retd), said that under the Armed Forces (Special Powers) Act (AFSPA), 1958, the army could detain suspects but was required to hand them over to the local police.

“The AFSPA gives powers to the Army to detain any suspect and then you are supposed to handover him to the police at the earliest possible opportunity,” Lt Gen Hooda told Article 14.

“Any person arrested and taken into custody under this Act and every property, arms, ammunition or explosive substance or any vehicle or vessel seized under this Act,” says the AFSPA, “shall be made over to the officer-in-charge of the nearest police station with the least possible delay, together with a report of the circumstances occasioning the arrest, or as the case may be, occasioning the seizure of such property, arms, ammunition or explosive substance or any vehicle or vessel, as the case may be.”

Absent: The Role Of Local Police

The AFSPA empowers the army to fire upon anyone in a “disturbed area” acting in “contravention of any law or order for the time being in force… even to the causing of death”.

The latest such case emerged on 16 December 2022, when two civilians were killed outside an army camp in Jammu’s Rajouri district. The army blamed “unidentified terrorists” for the “firing incident”. Relatives of the victims alleged that they were killed by an army sentry.

After widespread protests against the killing, the J&K police registered a first information report (FIR) and constituted a special investigation team to probe the killings.

The victims were identified as Surinder Kumar (38) and Kamal Kumar (40), residents of Muradpur in Jammu’s Rajouri district. A third man, Anil Kumar, a resident of Uttarakhand living near the camp, was injured.

Lt Gen Syed Ata Hasnain, former commander of the army’s Srinagar-based Chinar Corps, told Article 14 that under the AFSPA if the army had to detain terror suspects, local commanders usually did so for 24 hours in cooperation with the local police, as the law requires.

The distance between Rashid’s house in Kunan and the nearest police station in the town of Trehgam in Kupwara district is 3.5 km. An army unit from the 41 Rashtriya Rifles unit is stationed in Trehgam village, which means the unit commander could have informed the local police with little difficulty.

Lt Gen Hasnain said after 24 hours of detention, the army must hand over a suspect to the local police and ask for a certificate from the police that the suspect had been handed over in a “medically acceptable condition”.

“When the Army hands over the suspect to the police, it’s very important to contact a medical check-up of the suspect,” said Lt Gen Hasnain.

‘AFSPA Misused’

Over the years, various international and national human rights groups have criticised successive Indian governments for “misusing” the AFSPA in J&K and other disturbed areas.

Critics have argued that the AFSPA can lead to human-rights abuses, including extrajudicial killings, torture, and arbitrary detention.

In its latest report on 2 August 2022, HRW said that the AFSPA gives members of the armed forces effective “immunity from prosecution”.

“There has been no accountability for these recent alleged extrajudicial killings or past killings and abuses by security forces, in part because of the Armed Forces (Special Powers) Act (AFSPA), which gives members of the armed forces effective immunity from prosecution,” the HRW report said.

“Since the law came into force in Jammu and Kashmir in 1990, the Indian government has not granted permission to prosecute any security force personnel in civilian courts,” said the HRW report.

Rashid’s brother Shabir, the SPO, said when the army took away his brother, he called the local police station, where he was posted, and informed his colleagues what had happened.

SPOs are not regular police but hired on contract (without medical or risk allowances), particularly in areas riven with insurgency. They provide guard duties, can detain suspects, are paid between Rs 9,000 to Rs 18,000 and are integrated into daily police operations.

The next day, on 16 December, at around 9 am, the family went to the 41 Rashtriya Rifles camp in Trehgam, only to be told that their son had “fled from custody”.

“The soldiers told us to come at 4 pm, as the town commander was not available,” said Shabir.

That evening, the family said, they went back to the Trehgam army camp, this time with the station house officer (SHO) of the Trehgam police station.

“The officer went inside, and after some time he came out and said that the town commander informed him that Dar fled from their custody,” said Shabir.

The family said that the army told police that Rashid fled while leading the soldiers towards a supposed militant hideout in a forest called Marhama in the upper reaches of Kupwara.

“We even went to that place (Marhama forest) along with some people from our village but couldn't find anything,” said Shabir.

The agitated family expressed their shock, refused to believe the army, filed a missing-person complaint and over the next few days met senior police and administration officials.

According to the family, Kupwara’s deputy commissioner, Doifode Sagar Dattatray, assured them that they would find Rashid. Article 14 sought comment from Dattatray, but he did not respond to phone calls and text messages sent on 3 January 2022.

After a week, Rashid was still not found. So, the Dar family travelled to Srinagar and held a protest at a neighbourhood called the Press Enclave there, the site of similar protests by distressed families since the 1990s.

Latest Of Thousands To Vanish

The village of Kunan is more commonly known in conjunction with its twin, Poshpora.

It was here, 32 years ago on the night of 23 February 1991, that soldiers allegedly gang-raped anywhere from 23 to 100 women during an anti-insurgency operation, a claim that state has denied repeatedly.

Some of the women were from the contiguous village of Poshpora, with the alleged violence commonly known as the Kunan-Poshpora gangrape. No soldiers were arrested and the case has been pending in the Supreme Court since 2017.

On 28 June 2021, Article 14 reported the latest of these disappearances: a youth who went missing, according to his family, after allegedly being picked-up by the army in Doompora village of South Kashmir’s Shopian district on 29 November 2019.

Five United Nations human rights experts, including three special rapporteurs focusing on torture, extrajudicial executions and protection of human rights while countering terrorism, wrote a letter to the government of India, made public in June 2021, seeking details of “repressive measures and broader patterns of systemic infringements of fundamental rights”, in the Shopian case and two others.

The United Nations has been involved in Kashmir since 1947, when it mediated the first Indo-Pakistan war in the region. India has resisted UN’s involvement in the conflict and maintained that Kashmir is India’s “internal issue”.

In May 2019, India informed the Human Rights Council, a UN body, that it would not engage with its special rapporteurs on their Kashmir reports. In July 2019, the ministry of external affairs dismissed a UN report on the valley as being “false and motivated”.

When J&K was brought under New Delhi’s direct control in August 2019, the UN Office Of The High Commissioner for Human Rights criticised India’s action. Since then, UN-appointed independent experts have watched the situation in the region.

‘Enforced Disappearances’

Since armed insurgency erupted in the Muslim-majority Kashmir valley in the early 1990s, an advocacy group called the Association of Parents of Disappeared People (APDP) gathered data on the 8,000 civilians who disappeared.

The APDP, now almost defunct after raids and criminal cases in 2020, used to hold silent protests on the 10th of every month in Srinagar’s Pratap Park (which is next to the Press Enclave) against what they called “enforced disappearances” of family members. Thousands still wait for their return.

The families of disappeared people were assisted by the APDP and the Jammu Kashmir Coalition of Civil Society (JKCCS). Both groups are largely defunct after raids by the National Investigation Agency (NIA) in 2020 and 2021.

“We haven't held protest demonstrations now since 2019,” said an official from APDP speaking on condition of anonymity. “You know what the situation is right now, it’s difficult to operate under present circumstances.”

In November 2021, to global criticism, the NIA arrested Khurram Parvez, a prominent human rights activist, accused of charges under the Unlawful Activities Prevention Act (UAPA), 1967, as Article 14 reported. Parvez, 45, is the program coordinator of the JKCCS and the chair of the Asian Federation Against Involuntary Disappearances (AFAD).

Over the years, Parvez and his team had documented thousands of cases of enforced disappearances and investigated unmarked graves in Kashmir, a reason for his arrest, according to HRW.

While “enforced disappearances” declined over the 2010s, at least two (including Rashid’s) cases have been reported since the abrogation of Article 370, the special constitutional provision that allowed J&K limited autonomy, on 5 August 2019.

The J&K government while acknowledging such disappearances over the years, contested the APDP’s number, but its own figures have varied.

On 21 June 2003, the then home minister, A R Veeri, said 3,931 persons were reported missing from 1989 to June 2003, while former chief minister Ghulan Nabi Azad put the number at 1,017 since 1990.

In 2011, the then director general of police Kuldeep Khoda told The Hindu that police were willing to act if rights groups provided them an “authentic list” of disappeared persons.

“We are willing to work together with people to redress their grievances, but the lack of authenticity has made this difficult,” said Khoda.

In August 2011, the now-defunct Jammu and Kashmir State Human Rights Commission (SHRC) said that there were 2,156 unidentified bodies in ‘mass graves'.

The families of disappeared persons believe that their kin may have been killed and buried in these ‘mass graves’.

[[https://tribe.article-14.com/uploads/2023/01-January/06-Fri/Khera%20Begum.jpg]]

‘Independent Investigation Is Crucial’

A senior police official from Kupwara told Article 14 that although Rashid had no criminal record, his name emerged when the Kupwara police said they had busted alleged narcotics smugglers on 23 December 2020. Five policemen were among 17 arrested.

“While investigating the case further, Rashid's name cropped-up,” said the official, speaking on condition of anonymity since he was not authorised to speak to the media. He did not make clear the criminal nature of Rashid’s involvement.

“He has provided a SIM card to some terror suspects,” said the officer. “The SIM wasn’t in his name, but he had received it from someone. We were still investigating it, the case wasn’t clear yet.”

The official said police would have detained Rashid but were “waiting for further evidence”.

Senior superintendent of police (SSP) Kupwara Yougal Manhas told Article 14 that police considered Rashid “missing” and were investigating the case from two angles.

“We received a complaint from the family, and the next day from the Army unit that Rashid gave a slip to them and fled from their custody when they were taking him to a hideout,” said Manhas.

He said police had not yet registered an FIR but “if required cognizance would be taken”.

Gen Hasnain said if a suspect escaped from an army unit’s custody, disciplinary action could be taken against the unit personnel “after determining culpability”.

“First of all there will be a court of inquiry, which will determine the circumstance, the facts and ascertain responsibility,” said Gen Hasain. “Based on that responsibility, higher-ups will take cognizance of it and decide against whom disciplinary action needs to be taken.”

Ganguly of HRW said disappearances such as Rashid’s could be addressed by “a strong and independent civil society, including human rights groups, media and also the judiciary and human rights commission”, who could have intervened to “investigate and establish the facts”.

“The breakdown of such institutions harms the building of trust between communities and security forces,” said Ganguly.

Back in Kunan, Rashid’s mother said she wanted answers from the army and feared her son might be dead.

“They have robbed me of my peace,” said Begum Khera. “I want to set myself ablaze before the army camp. I just want to see my son once. If he has committed any crime, the army should tell us. If they want to jail him after that, I won’t say anything, but let them show his face to us. We want to know where he is.”

Get exclusive access to new databases, expert analyses, weekly newsletters, book excerpts and new ideas on democracy, law and society in India. Subscribe to Article 14.

(Auqib Javeed is an independent journalist based in Srinagar.)