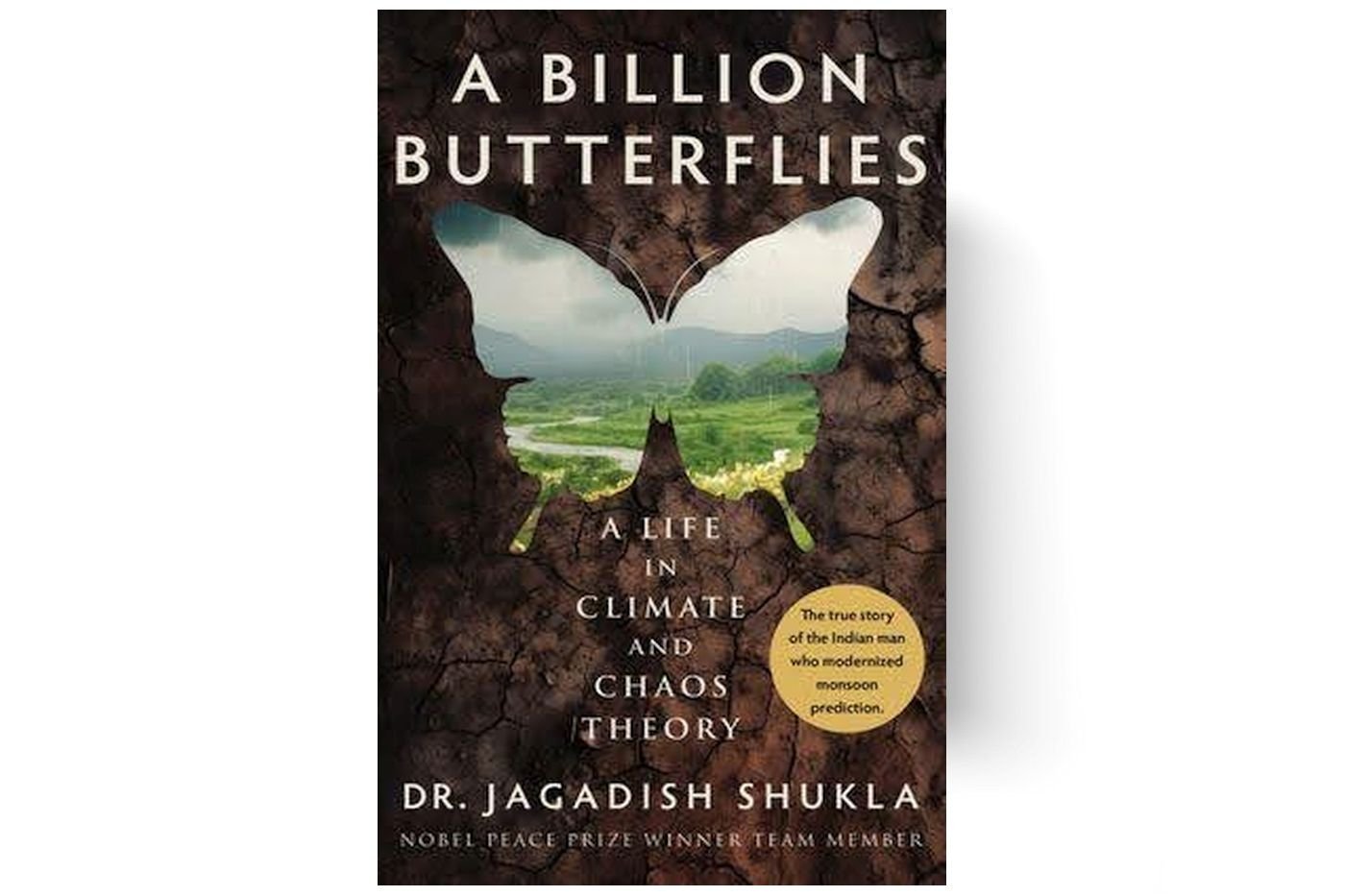

In advance praise for A Billion Butterflies: A Life In Climate & Chaos Theory by meteorologist Dr Jagadish Shukla, Rob Wesson, geophysicist and author of Darwin’s First Theory, calls this the “almost magical story of a barefoot boy who rises from a tiny Indian village and discovers how to predict the previously unpredictable monsoon rains—upon which the fragile supply of food for his village and thousands like it depend.”

Shukla is professor of climate dynamics at George Mason University. For his work as a lead author for the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change’s 4th assessment, his team was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize in 2007, along with Al Gore. Internationally recognised for his role in the development of weather and climate science, he is a recipient of the United Nations’ International Meteorological Prize and the Exceptional Scientific Achievement Medal from NASA, the highest honour to civilians from the space agency.

Born in a village of about 1,500 people in eastern Uttar Pradesh, Shukla, who studied at the Indian Institute of Tropical Meteorology before attending MIT and Princeton, spent a childhood marked by floods, droughts and crop loss. A New York Times report found even in 2003 that Mirdha village received power for no more than eight hours a day, plunging into blackness at night; water was supplied through hand pumps; residents had to relieve themselves in the open; and the primary school, with no desks or chairs, saw 70% of its students dropping out before high school.

It was Shukla’s philanthropic work in Mirdha that took the NYT there—a community college, a special programme for out-of-school children, healthcare, and more. “Professor Shukla's subversive goal is to teach Gandhian principles—honesty, perseverance, selflessness—in a country where they are increasingly unfashionable,” the article said.

Shukla himself writes about his native village evocatively: “In Mirdha, the monsoon wasn’t simply one thing. It was everything: a governing body, a gift from the gods, a holiday, a common language. Back then, however, we had no idea why it came or why it didn’t or that its arrival was heralded by forces many hundreds of miles away from our tiny, dusty village.”

In this deeply personal book, a climate scientist traces his journey from this childhood to a life of scientific inquiry and global climate advocacy. With clarity and urgency, he connects the dots between lived experience, meteorological breakthroughs, and the moral imperative of climate action.

Excerpt

When I was growing up, the weather dictated my life: the food I ate (or didn’t), the water I bathed with (or didn’t), the days I spent hidden in a mango tree or curled in my mother’s lap. As I got older, I moved between climate-controlled apartments and cities with snow-plows, and the weather seemed less like an adversary to be feared and more like a curiosity, something to be understood, to be dissected and taxonomized. Eventually, when my academic interests turned to seasonal climate and beyond, I lost interest in the day-to-day weather altogether.

I’m not the only one. For many decades now, humans have lived as if we were in charge, finding ways to work around the weather. We’ve constructed levees, built large-scale irrigation systems, settled in places our ancestors could survive in for only seasons at a time.

No one and nothing tells us what to do.

Except the weather is beginning to demand our attention. The brutal heat, the unprecedented floods: extreme events like these are no longer relegated to only the poor and far-flung populations of the world. The weather that arrives on my suburban doorstep every day is once again capricious and chaotic—just as it seemed when I was a village boy. I know this causes many people to experience climate anxiety, and I do not blame them. I know firsthand how the world can feel like a cruel and random place. Things are unlikely to get better soon, and extreme weather is here to stay. But there is reason for hope.

I believe that to manage and mitigate climate change we need three things, and the good news is that we already have the first two well in hand. First, we need to understand the science. Check. Second, we need the technology that allows us to stop pumping the air full of carbon dioxide. Check. Third, we need the will to listen to the science and embrace the technology. It is only on this last point that we are stuck, thanks to the corporate greed that has parasitized our political system.

Just forty years ago, society found itself in a very similar situation. Chlorofluorocarbons, a harmful greenhouse gas used in foams, aerosols, and air conditioners, had torn a hole in the ozone layer, the planet’s natural protection against the sun’s damaging radiation. Fixing it required listening to the scientists issuing dire warnings, developing new technologies, and calling for action. In 1987, just two years after the hole was detected, forty-six countries entered into the Montreal Protocol, committing to phasing out harmful chlorofluorocarbons. In 2008, it was the first and only UN environmental agreement to be ratified by every country in the world. Today, virtually all ozone-depleting substances have been phased out of production, and the ozone hole is expected to close by the 2060s.

Although it often feels like we are subject to a never-ending highlight reel of disasters and news that makes us feel hopeless, there really are, just like the story of the ozone hole, hopeful signs of climate science to be found in the world, reasons to stay optimistic. Sales of electric cars are booming. In the United States and Europe, emissions of CO2 peaked in 2005 and 1979, respectively. Wind farms are slowly rising over the Atlantic Ocean, and more than 80 percent of new utility-scale energy sources in America are renewables. Recently, a group of teenagers sued the state of Montana for jeopardizing their right to a clean and healthful environment— and won! The road ahead is long, but we have already started way down it.

I may be biased, but I would argue that meteorology represents our species’ longest and most concerted effort to take care of one another. Indeed, it is easy to forget all we have accomplished. Five hundred years ago, humans couldn’t begin to guess what caused the wind to blow or the sky to burst open with rain; it was the gods, they surmised, or the stars or the exhalations of the earth itself. One hundred years ago, the idea of producing an accurate weekly weather forecast was an impossible fantasy. Fifty years ago, the notion of predicting the climate months in the future wasn’t just laughable—it was thought to be a scientific impossibility.

And yet, a tiny glimmer of hope inside a boy from a remote corner of India—nurtured by teacher after teacher—became the scientific basis for that very notion. Today, because of that boy’s optimistic hunch, societies around the world are able to plan for the future, to prepare for and head off disaster. My own work was possible only because of the many indefatigable dreamers who came before me, the scientists who figured out the laws that govern the atmosphere, a method for finding order amid chaos.

It is true that the future scientists who are growing up today will face perhaps a more

profound challenge than ever before. But as someone who has witnessed, time and time again, brilliant scientists gather from every corner of the globe and set aside political, religious, and cultural differences to overcome seemingly insurmountable challenges—I have faith they will rise to the occasion. Plus, tomorrow’s meteorologists and climate scientists have some pretty neat technology on their side: machine learning and artificial intelligence, not to mention smarter satellites and faster computers, which will get even faster with quantum computing, enabling Earth system models of staggering resolution.

In the end, though, it won’t be the models that save us. Nor will it be the supercomputers or the IPCC assessment reports or the climate NGOs. It will not be the climate scientists alone. It will be every person who takes personal responsibility for future generations and chooses to act, whether we do that by changing our consumption, volunteering our time for environmental nonprofits, casting our votes for politicians who prioritize climate action, or even just sitting down to write letters when we are so moved. As I tell my students, the best response to climate anxiety is climate action.

Our climate is changing, and our planet is in trouble. The path ahead can sometimes feel frightening and uncertain. But I have found predictability in the midst of chaos, a safe place to retreat when the storms are raging and the butterflies swarm. For me, it has been in the steady and unending work of making the world a better place.

I hope you will join me there.

(Excerpted with permission from A Billion Butterflies: A Life in Climate & Chaos Theory, published by Pan Macmillan India.)

Get exclusive access to new databases, expert analyses, weekly newsletters, book excerpts and new ideas on democracy, law and society in India. Subscribe to Article 14.