Srinagar: When you talk to M* (name withheld on request), he can discuss organic synthesis and heterocyclic chemistry, subjects during his final year studying for a master’s degree in chemistry in 2016 at the University of Kashmir, where he scored more than 65%.

Dressed in a red shirt and trouser and sporting a stubble, M dreamed of studying further, acquiring a PhD and becoming an academic, perhaps finding work as a teacher or lecturer and eventually making enough to pull his family out of poverty.

But when his father, a labourer, died of a heart attack in 2017 at his home in Sumbal, a town in Bandipora district, about 30 km north west of Srinagar, he started looking for a job soon after graduation. He got offers to work as a teacher, a salesperson and a shop assistant, but none of these fit his ambitions.

The only job that sounded somewhat reasonable was to teach science to seventh and eighth standard students at a private school—for Rs 8,000.

“A day labourer earns more than that,” said M. The school said it could not pay him more because of the loss of revenue when it was shut for five months after the government of Prime Minister Narendra Modi in August 2019 wrote down Article 370, the special constitutional provision that allowed Jammu and Kashmir’s (J&K) accession to India in 1947.

“This amount was not sufficient enough for me to feed my family,” said M*.

Today, he works eight hours a day, six days a week to earn about Rs 12,000 per month—at a construction site, mostly carting bricks.

It was not supposed to be this way for M and thousands like him because Modi had often declared (here and here) that the abrogation of Article 370 would herald a new era of development and prosperity for conflict-ridden J&K, especially its youth.

“We have to build a naya (new) Kashmir,” Modi said at a public rally in September 2019. “The decision to revoke Article 370 was for the unity of India and it is going to fulfil the aspiration and dreams of the people of Jammu and Kashmir.”

Now, more than two years later, Modi is making new promises and repeating old ones.

Modi Promises An End To ‘Miseries’ of J&K Youth

On 24 April 2022, Modi, while announcing an investment of about Rs 20,000 crore, promised an end to the “miseries” of the youth of J&K.

“I want to tell the youth of J&K to have faith in my words,” said Modi. “You will not see the miseries witnessed by your parents and grandparents.”

But across the union territory, the policies of his government have, said experts, increased unemployment, forcing the educated unemployed to take whatever jobs they can.

Many youth find themselves without jobs, while countless others, who had one, lost them to lockdowns or had their livelihood impacted.

Jammu and Kashmir’s unemployment crisis worsened after Article 370 was abrogated, reducing the former state to a union territory directly governed from New Delhi.

A stifling five-month security lockdown and frequent Internet shutdowns devastated many businesses after the 5 August 2019 decision, with a July 2020 study by the Kashmir Chamber of Commerce and Industries (KCCI) estimating that Kashmir’s economy faced a loss of Rs 40,000 crore due to the shutdowns. The pandemic exacerbated these losses although there is no estimate of what these might be.

The lack of jobs in Kashmir has unfolded against a larger job crisis across the country, with more than half of India’s workforce of 900 million no longer even looking for work, according to April 2022 data from the Centre for Monitoring Indian Economy (CMIE), a private research agency.

CMIE reported that Jammu and Kashmir’s unemployment rate for the month of March 2022 was 25%, almost three times the national average for the month, 7.60%, and second-highest after Haryana’s 26.7%.

Unemployment among educated youth in Jammu and Kashmir was 46.3%, only behind Kerala where the number is 47%, according to the union ministry of statistics and programme implementation’s Periodic Work Force Survey for April-June 2021, the latest available data.

“Millions left the labour markets,” wrote CMIE’s Mahesh Vyas of India’s job crisis. “They stopped even looking for employment, possibly too disappointed with their failure to get a job and under the belief that there were no jobs available.”

That is certainly the case with Mohtashim, 31, and Moazzam, 26, unemployed brothers from Srinagar, both engineers. Both men, who requested we only use their first names, graduated in 2016 and 2019, respectively, and since unsuccessfully applied for jobs as junior engineers with the J&K government. Their mother died some years ago and they care for an aged father.

“I could have had a job outside (J&K), but I can’t leave my father behind,” said Mohtashim. “So, I am looking for a job here, but that is difficult because there are only limited opportunities in the government sector.”

Mohtashim said their father had urged him to marry, but the marriage prospects of unemployed young men, he said, were “very bleak”.

Unemployment in J&K, which has a literacy rate of 67%, was always a problem, but there is little doubt, said experts, that it was exacerbated by the tension and sweeping security crackdowns after Modi’s government struck off Article 370 without consulting J&K’s electorate.

How Jobs Dried Up After Article 370 Abrogation

In 2018, Jaffer Ali, 30, an engineering graduate in computer sciences, had a business idea.

Ali and three friends had discussed the Kashmir Valley’s sub-standard public transport and believed an app-based taxi service could be profitable and generate jobs. They started the company in 2018, after three years of preparation and investing Rs 600,000.

“We had everything ready,” said Ali. “We had tied up with cab drivers and auto rickshaws across Kashmir, even the registration was complete.”

But since many cab drivers were busy with the annual Amarnath yatra in July-August 2019, a major Hindu pilgrimage, they decided to launch the service after the yatra ended. Before the yatra ended, the government announced the end of J&K’s statehood, its special constitutional status and imposed a sweeping security lockdown, including a preliminary 53-day curfew and snapped the Internet.

The app-based taxi project went bust. Ali and his friends moved out of Kashmir in search of a job, abandoned the project and lost the money they invested in creating an online platform and purchasing software.

More than the money, Ali, who is an engineer today in the corporate sector, said it was the three years they invested in the project that they regret most. “Time is a priceless commodity,” said Ali. “You cannot put a price tag to it.”

The security shutdown affected not just engineers but those less educated, such as Dilawar Mir, 34, a 10-standard pass from south Kashmir’s Pulwama district. Before 2019, Mir drove a passenger cab that he hired on the Pulwama-Srinagar route. He figured buying his own cab was a good idea, since he would no longer have to pay Rs 15,000 of the Rs Rs 22-24,000 he earned every month as rent.

Mir took out a bank loan and sold a small patch of land to buy a Chevrolet Tavera for Rs 750,000. He ran his cab for a month. Then came the Article 370 revocation and the seemingly unending curfews. Mir recalled being at home for five months without earning anything.

In January 2020, Mir saw a ray of hope, as the government relaxed the curfew. But then came the Covid-19 pandemic and another set of successive shutdowns, longer than the rest of India, upending Mir’s world and everything that embodied normalcy in Kashmir.

With a family of four to provide for and a loan to settle, Mir sold his cab in less than a year. “I faced immense losses,” said Mir. He tried renting a cab again, but the rental costs were now too high.

Now, when he finds one, Mir does the odd labour job at construction sites, making cement for masons or laying bricks, or whiles away the time at home.

After August 2019, An Unemployment Surge

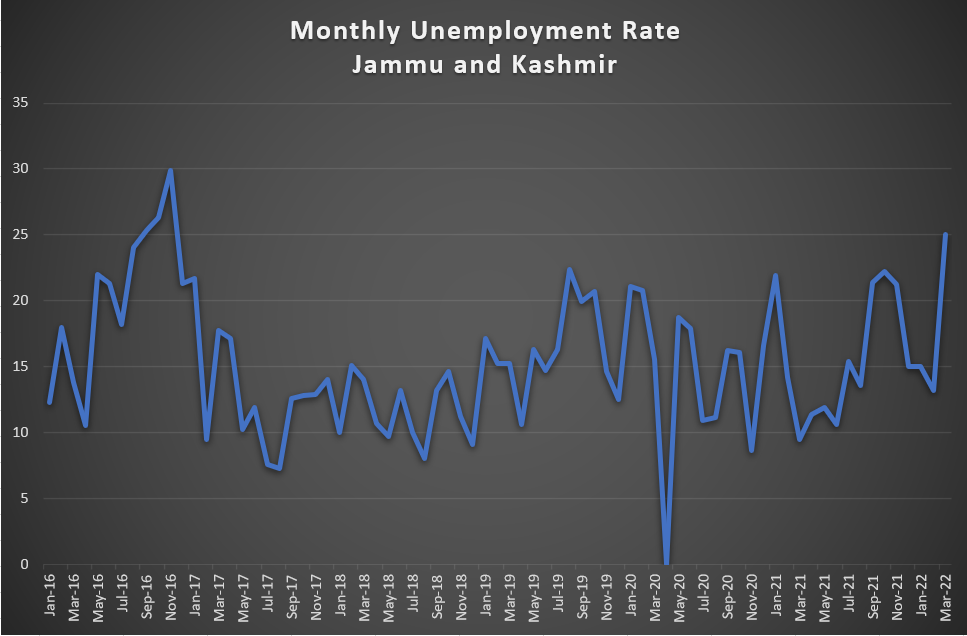

Since Article 370 was revoked in August 2019, the unemployment rate rose above 20% nine times, according to CMIE data.

It has only been worse in 2016, when mass unrest swept the Valley for fie months after the killing of militant commander Burhan Wani. Rolling curfews crippled the economy and the unemployment rate was 30%.

Since then, the average annual unemployment rate in J&K for 2017 was 12.98% and 11.56% in 2018, according to CMIE data. In 2019, it was 16.29%, 15.77% in 2020, 15.69% in 2021 and 17.3% so far in 2022.

J&K has a workforce of 4.5 million people, said Ejaz Ayoub, an economic researcher. The current employment rate of 25% translates to 1.1 million out of work, a quarter of the workforce. Referring to recently released government data for April-June 2021 from the National Statistics Office, (NSO), Ayoub said that if 46% of educated youth were unemployed, it meant “almost half the educated workforce is sitting at home”.

The Problem With Government Jobs

Ayoub said only the government sector, which employs around 450,000 and construction, which employs around 700,000 people, stayed afloat. Tourism, which employs an indeterminate number of people, has lately seen a turnaround, with 8 million tourists visiting over the past six months, according to lieutenant governor Manoj Sinha, but as Ayoub said, “Kashmir is not tourism only”.

The J&K administration, according to official data quoted in the Hindustan Times, advertised around 10,000 jobs in 2021, but contentious new domicile laws mean that outsiders can also apply for many jobs, at a time when the job market and economy are shrinking.

Without a limited private sector, government jobs are coveted in J&K. In June 202, when the Jammu and Kashmir Services Selection Board (JKSSB) advertised more than 8,000 posts for what are called “class IV employees'”, the lowest level, such as peons, sweepers and security guards, more than half a million people applied, many with graduate and postgraduate degrees. Class IV employees are the lowest level.

When officials observed that 62 times as many people applied than there were vacancies, the JKSSB issued an order that asked “overqualified”—the minimum qualifications were a 12th-standard graduation—application to withdraw voluntarily or risk being punished by never being considered for a JKSSB job again.

Eventually, the matter went to court, when a candidate filed a petition. The J&K High Court in its November 2021 order said the JKSSB order was justified since those with higher qualifications “may not be in a position to discard the (sic) menial work”, they would score higher and, if selected, “would always be looking for a better job”.

The Domino Effect Of Unemployment

Unemployment has a domino effect, said Ayoub, as households who depend on those working fall back on savings when there are no jobs.

“If they don’t have savings, they borrow,” he said. “Slowly, if they don’t regain their income source, they start sliding towards poverty.”

The poverty ratio in Jammu and Kashmir as per 2011 census was 10.35% against the national average of almost 22%. But appeared to have worsened over the years of unrest, with a 2021 multidimensional poverty index created by the NITI Aayog, the union government think tank, based on 2015-16 data, finding nearly 13% of J&K “multidimensionally poor”.

The pandemic clearly worsened poverty, according to anecdotal evidence.

“During Covid, we saw that there was a demand for food packets,” said Ayoub. “We rarely saw that previously. So, that is a big indicator. You (also) have suicides, drug abuse, mental illness rampant nowadays. These are socio- economic indicators of joblessness. Although its major trigger was Covid, before that unprecedented economic decline happened due to abrogation.”

Investments, Jobs & Government Claims

J&K’s unemployment figures appear to be out of sync with government claims (here and here) of job creations and new investments after the abrogation of Article 370.

An April 2022 government statement said that over the next six months, an investment of around Rs 70,000 crore would create about 700,000 jobs. The government has been trying to woo investors from the Middle East and get them to invest in J&K, announcing in January 2022 a series of investments.

Even if investments materialised, said Ayoub, it could take up to a decade for them to take effect in terms of jobs.

“But to address short-term unemployment, there should have been short- term measures,” said Ayoub. “You are not hand holding local businesses. They are not being bailed out. They are the ones who can create jobs.”

Sheikh Ashiq, President of the KCCI, said businesses currently were in no position to create new jobs or even support the ones they once did.

“We want the present businesses, industries, tourism, handicrafts and export-oriented industries, to be given assistance, so that they stabilise and generate employment,” said Ashiq.

He said that they had suggested to the government that it help in the revival of businesses by bankrolling those that now had “non-performing assets”, jargon for bad debts, while those that could be revived be given “an honourable exit” via a one-time settlement of debts.

An Entrepreneur’s Hopes Crushed

T* (name withheld on request), 43, can tell how the end of statehood ruined his fledgling business, ended his entrepreneurial dreams and left him with debts of Rs 800,000.

After working almost two decades in the pharmaceutical sector, in 2019 T decided to resign from “well-paid” job as a sales manager to invest his savings of more than Rs 600,000 and take a loan of Rs 800,000 to register a company marketing generic medicine.

“Everything was smooth,” said T. But when the curfews after the loss of statehood began, the decision to strike out on his own appeared to be a mistake. With the Kashmir Valley off the communications grid and shutdowns continuing on and off for more than a year, the business bore losses it could not sustain, as many medicines ran past their expiry dates.

“When everything was shut, we couldn’t make sales,” said T. “ Most of the stock expired.” When hospitals shut their out-patient departments as the pandemic struck, the market was further hit.

“Lockdowns brought me to my knees,” said T.

In April 2021, when he tried to get back his job as a medical representative, he was told to start at the bottom.

“Life has been really tough since that fateful day. I lost my money, my career, job, everything to these lockdowns,” said T, who did get back his old job, but at a third of the salary he earned before J&K became a union territory. “Only hope,” he said, “keeps me going.”

(Minhaj Masoodi and Zakia Qurashi are independent journalists based in Kashmir.)