Bolangir district, western Odisha: It was 11 pm, 15 minutes to the arrival of the Korba Visakhapatnam Link Express on platform number one of Kantabanji railway station.

Gaurav Bhoi and his siblings from Ainlabhata village, instructed to board this train by S*, their labour contractor or sardar, were nowhere on the platform. In fact, none of the few hundred migrating families who were to board the train that day, 12 December 2022, were seen near the slots for general compartments though they all had orders to take the train and head for the brick kilns in Visakhapatnam and other places in south India.

Kantabanji railway station, located in the underdeveloped Kalahandi-Bolangir-Koraput or KBK region, is Odisha’s biggest hub of migrating labourers. On the platform, however, only a few middle-class passengers idled near the spots where the reserved compartments would halt.

A police chowki next to the platform’s main entrance bore a banner promoting ‘Mission Uddhar’ for ‘protection of migrant workers’. A similar chowki outside the station had a lone, bored policeman scanning his mobile phone.

Around 15-20 young men milled about at one end of the platform, dispersed into three-four groups, their eyes watching over everyone present. They listened to announcements about the train’s imminent arrival, and engaged in hushed conversations. The middle class families adjusted their positions according to coach numbers displayed on overhead boards.

There was still no sign of the Bhois and other migrant families.

Before the Covid-19 pandemic, there were no police chowkis, and migrant families camped on either end of the platform with numerous bags and utensils for hours. A campaign on safe migration launched in 2021 by the Odisha police in the eight districts that form the KBK region led to a crackdown on labour trafficking at the Kantabanji, Turikela, Harishankar Road and other railway stations.

The police arrested a number of sardars under section 370 of the Indian Penal Code (IPC), 1860 (buying or disposing of any person as a slave), and made migrating families witnesses in these cases.

Gaurav Bhoi and his siblings, like most other migrating families waiting to board the train in Kantabanji, were not registered under the Inter-State Migrant Workmen (Regulation of Employment and Conditions of Service) Act (ISMWA), 1979. They also had no written agreement or contract with their sardars specifying their employer, place and period of work. This meant their journeys could be implicated as cases of human trafficking.

As the clock crept past 11.15 pm, it appeared that the Bhois would not be able to board their train to Visakhapatnam and travel onwards to Hyderabad, where they were to work at a brick kiln under a system of debt bondage outlawed in 1976.

Suddenly, with the train a few hundred metres short of the platform, the Bhois and scores of other migrant families streamed in through makeshift entrances to the platform located near the general compartments. The 15-20 young men who had been milling about rushed to take control, split the labourers into groups, and helped them board the already crush-packed general compartments.

Some of the young men boarded the train as it departed the station, others left the premises.

The whole operation was over in 10 minutes. Similar operations unfolded in Turikela, Harishankar Road and other railway stations in the KBK region when trains headed to Andhra Pradesh, Telangana and other states in south India were scheduled to halt there. Sometimes, trains halted for longer than the scheduled stop to accommodate the rush.

The second of a four-part series on the persistence of modern slavery and human trafficking in India, this report describes the organised networks that assist and enrich traffickers. The first part explored the magnitude of distress in rural western Odisha that has prompted growing numbers of poor to seek out such work despite a 47-year-old law abolishing bonded labour in India; while parts three and four will consider the conditions of work for bonded labourers, the denial of law-mandated protections for them and the long-term consequences on their health and wellbeing.

How Traffickers Beat Police, Vigilance Systems

The police crackdown on human trafficking in the KBK region since 2021 hit sardars hard. In just the September2022-November 2022 period, the Odisha police arrested more than 65 sardars.

Between late 2021 and early 2023, covering two annual migration cycles, 35 first information reports (FIRs) were registered in Khaprakhol police station alone, one of the regions with a high out-migration rate. The FIRs were filed under IPC sections 370, 371 (habitual dealing in slaves) and 374 (unlawful compulsory labour).

Before 2021, the Khaprakhol police station registered barely four to five cases annually under these sections of law.

However, during a nine-month investigation spread across the KBK region and the brick kilns of Andhra Pradesh and Telangana, Article 14 found operations to transport migrant workers, the large majority of them unregistered and undocumented, continuing to thrive, with meticulous planning and coordination, including with government, railway and police officials.

In a region facing acute poverty and low levels of human development (four of the KBK region’s eight districts had between 33% and 45% of the population categorised as multidimensionally poor), the number of workers seeking to migrate to work under harsh conditions remained high.

Meanwhile, the response of the sardars to the crackdown was quick. They hosted kiln owners, who visited Kantabanji and other hubs of migration and trafficking every year after the Nuakhai (kharif harvest) festival in mid-September, in remote villages instead of lodges in Kantabanji, where police vigilance was high.

They registered a fraction of their recruits under the ISMWA, at times by enlisting the services of local non-profits.

They routed a part of the traffic by road and resorted to online railway ticketing to escape surveillance at stations.

Sardars usually struck deals with kiln owners for the supply of batches of labourers, accepted an advance payment meant to be disbursed to labourers, while second and third-level sardars scouted for workers in villages, and undertook the risky job of transporting the migrating families.

If these families were intercepted by police or implicated in trafficking cases, sardars had to pay for the resulting losses to kiln owners. Often, intercepted workers were detained by police instead of shown as ‘rescued’, and sardars were required to pay cash bribes to have the men released.

The sardars worked in close coordination with specialised intermediaries for inter-state movement, also known as sardars. Both sets of intermediaries claimed they regularly bribed police and labour department officials to secure safe passage for recruited workers.

After the crackdown, they continued paying bribes, but at higher rates, to village committees, police officials, railway and labour department officials and reporters to enable smooth movement of workers.

Meanwhile, lakhs of workers like Gaurav Bhoi and his siblings endured inhuman conditions to reach their destination, just as they had done before the crackdown. They travelled in cramped, overcrowded railway compartments on long journeys that often involved changing trains, always overseen by handlers, and denied the displacement and journey allowances mandated under the ISWMA.

Mandated Displacement, Journey Allowances Unpaid

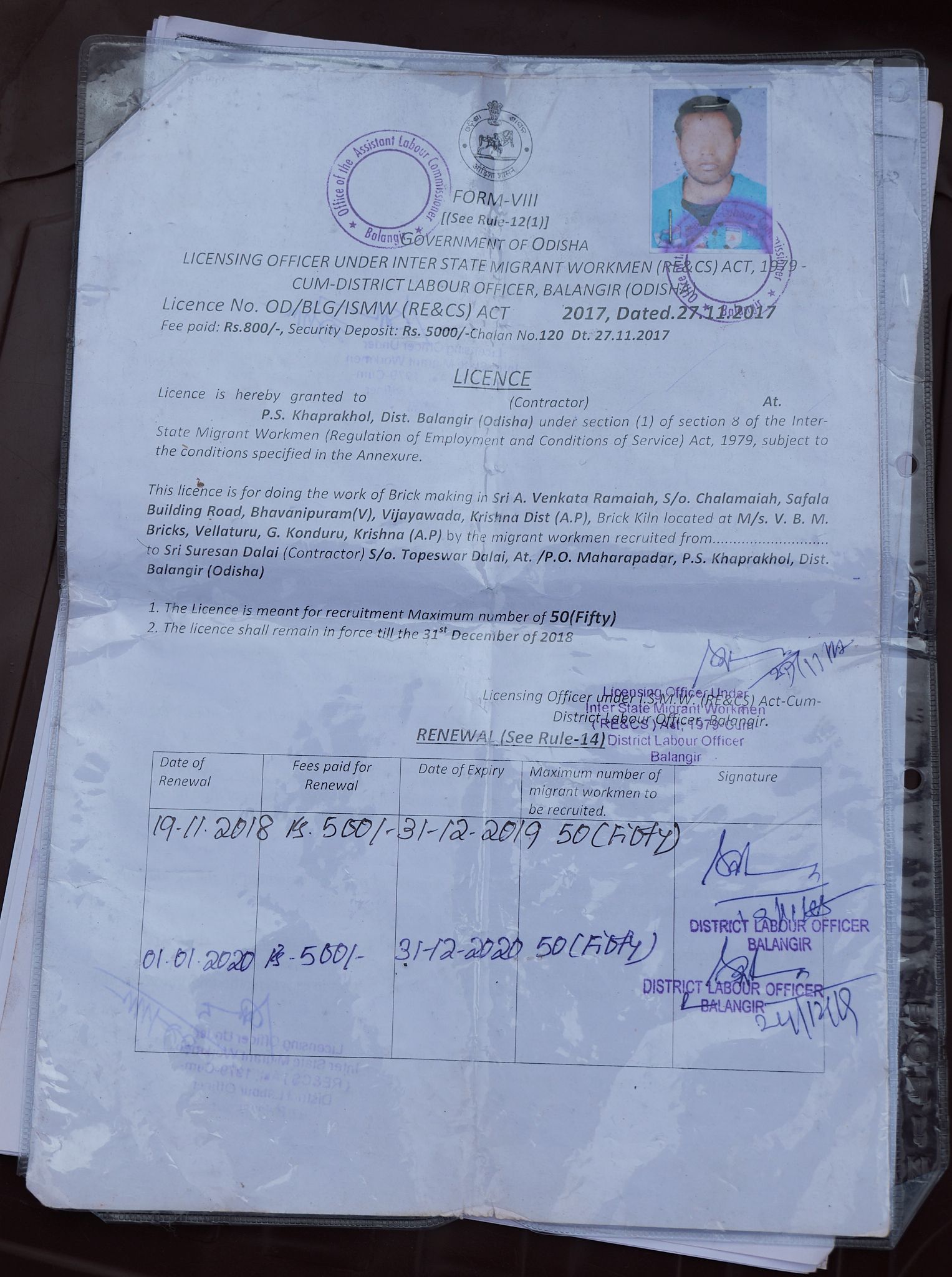

Chapter 3 of the ISMWA mandated that all sardars who recruited five or more inter-state migrant workers should obtain a licence from the home state mentioning the location of the worksite(s), nature and hours of work, remuneration and other relevant details. They were also mandated to furnish details of all workers deployed at such sites in the home as well as destination states within 15 days of recruitment/ joining work.

Sardars in the KBK region largely abided by this provision, especially in recent years, but they grossly underreported the number of recruits. For instance, two sardars showed Article 14 licences that mentioned 50 recruits, but said they sent more than 200 workers.

So, it was not surprising that S, their sardar, asked Gaurav Bhoi and his siblings to be cautious when they met him at his residence in Nunhaad village. His instructions to them were brief and clear.

They were to travel from Nunhaad to Kantabanji railway station by bus, and meet their handler, who would put them on the train to Visakhapatnam. From there, they were to take another train to Hyderabad, followed by a private cab to Rajni seth’s brick kiln.

If any policeman or person of authority questioned them along the way, they were to pose as tourists. Under no circumstances were they to reveal that they were brick kiln workers or that S was their sardar.

S gave the Bhoi siblings Rs 1,000 for the journey—around Rs 400 was for four unreserved tickets to Hyderabad, and the rest was for food and other expenses along the way. Section 14 of the ISMWA, on the other hand, mandates a displacement allowance equal to 50% of monthly wages or Rs 75, whichever is higher.

The Bhois earned approximately Rs 13,333 per person per month, bringing the law-mandated allowance to Rs 6,500 per person.

The bus journey to Kantabanji was uneventful, and the handler who met them outside the railway station took them to a dark, secluded spot beside the railway tracks, at a stone’s throw from the platform. They waited there with other migrant families, watched over by handlers.

“They gave us biryani for dinner, and liquor for those who drank,” Gaurav Bhoi said. “They also gave tickets to other families, but since we had not taken any advance, we bought our tickets ourselves.”

Senior advocate Gayatri Singh, co-founder of the Human Rights Law Network, said the reason the ISMWA was not implemented was because it benefits employers to ensure the law is not enforced. “The government is not firm and there is no machinery or manpower to implement the law,” she told Article 14.

She said workers refrained from registering complaints about violations as they feared labour contractors and owners, who would throw them out upon finding out about a complaint. “The only entities that can intervene on their behalf are unions and civil society organisations. But even they don't manage to leave much impact on workers,” she said.

“We Are Solving The Problem Of Unemployment”

The houses of the sardars were easily identifiable in villages around Kantabanji and other major transit points in the KBK region.

Most village homes had brick walls and tiled or thatched roofs, while a few owned single-storey or two-storey houses. Sardars, on the other hand, lived in multi-storey houses or elaborately laid out bungalows, with large compounds, high boundary walls, and security guards stationed at the gates. Some had a reputation for being ruthless with migrant workers’ families while recovering loans, some were rumoured to carry firearms and weapons, and villagers said some others bought a new car every other year.

Some sardars in Bolangir district’s Belpada and Khaprakhol blocks met Article 14 and explained how they worked, where they made money, and how much they earned per season.

They made money in three key ways, the sardars said.

They routinely advanced less money to migrating families than paid in advance by kiln owners. The actual amount disbursed depended on the circumstances and bargaining power of migrating families, and their relations with the sardar.

They also sent migrants to destination states by train in unreserved compartments, which helped save 70%-80% of transportation fees levied on kiln owners.

They also received a commission from owners at the end of the season. The amount was calculated on a piece-rate basis, and hovered around 10%-20% of the wages paid to recruits.

Every sardar had 10-30 henchmen, called second-level or third-level sardars, whose primary job was to stay in touch with families during the off season and spot opportunities for extending credit.

“Suppose a family needs Rs 2,000 for medical expenses, or Rs 5,000 to buy agricultural inputs, they ask me, and I go and tell the sardar,” said J, a second-level sardar from Dhamnimal village in Khaprakhol. The sardar fronts the money, reimburses the henchman for petrol for his bike, hands over a few pouches of country liquor, and adds another Rs 100-Rs 200 for miscellaneous expenses.

Sardars generally advanced these small loans without any interest, and deducted them from the lump sum advance paid to families prior to migration.

“We are solving the problem of unemployment in this region,” said one prominent sardar. “If we cease work, there will be a sharp spike in cases of robbery and petty theft, as the people are extremely poor and no jobs are available locally. Yet, we are treated like criminals.”

The affluence of prominent sardars was the stuff of lore for villagers.

In September 2022, when Article 14 was in Ainlabhata, Gaurav Bhoi’s village, a swanky white sedan whizzed past, leaving behind a trail of dust and a collective sigh.

“He changes his car every other season,” exclaimed Nira Kar, Gaurav Bhoi’s maternal cousin and friend who had been working in brick kilns since he was eight, sparking off a guessing game about the makes and names of S’s past and present four-wheelers.

According to the Bhoi siblings’ uncle Omkar Kharsil, who supplied construction workers to big contractors in Lanjigarh, sardars invested their money in gold and land, including in the names of their wives, children, relatives, domestic help and other pliable villagers. “The clothes they wear, the chadar (shawl) they drape…so soft…even (chief minister Naveen) Patnaik doesn’t have such stuff,” said Kharsil.

Payoffs And Risks For Traffickers

Although the sardars led a lavish life, their trade involved payoffs at multiple levels.

In villages where they recruited labour, sardars paid annual donations to village committees, mostly for construction of temples. They also paid these committees a stipulated amount (Rs 1,000-Rs 1,500) per family that migrated to another state.

Bribes to police and labour department officials came next, to ward off raids and legal cases.

Sardars also paid bribes to railway officials and police, to ensure trains halted a few minutes longer than scheduled to accommodate the rush of migrant workers.

Despite the bribes, sardars were exposed to high risks.

The first, and most widespread, risk was police, journalists and village-level authorities such as gaontias (a local title dating back to the colonial era, given to whoever bid the highest lease amount for land tax collections), priests and panchayat members spotting workers on the move, and demanding a ransom to let them proceed further.

Ransom demands ranged from a few thousand to a few lakh rupees, depending on the number of intercepted workers. Refusal to pay could delay the departure of workers and/or lead to trafficking cases, so sardars usually conceded to such demands.

Some paid bribes even when workers were registered under the ISWMA.

“Last year, when the police stopped a pick-up van carrying my workers to the station, they took Rs 1,000 per (unregistered) worker. But even for registered workers, they took Rs 500 per head,” said SD, a sardar from Khaprakhol block who supplied around 500 workers to kiln owners in Telangana and Andhra Pradesh. “What’s the point of registering workers then?”

SD enlisted the services of a non-profit in Belpada block to comply with provisions of the ISMWA for about 75 of his recruits.

Police cases against sardars or their henchmen comprised the second major risk in their trade. They were registered following raids or tip-offs about the movement of workers, who were “rescued” and turned back to their villages. Often, workers were also roped in as witnesses by police.

Every case of trafficking drained at least a few lakh rupees of a sardar’s wealth.

GT, a prominent sardar from Belpada block who supplied over 5,000 workers to kiln owners in Andhra and Telangana, explained why and how this happened.

“If the police catch 20 workers and register a case against my men, we stand to lose over Rs 10 lakh,” he said. “This includes Rs 1 lakh spent on their tickets and transport, Rs 8 lakh paid as advance, legal expenses to counter the charges in court, and Rs 1 lakh or more as bribes for police and politicians.”

If he was himself accused and imprisoned in such cases, the losses would be higher.

“I may have handed out Rs 30 lakh - Rs 40 lakh as advance to families in different villages. If I go to jail for long, all this money will be lost,” he said.

The third prominent risk that sardars contended with was of workers fleeing or being rescued from brick kilns mid-season. Highly exploitative conditions at worksites (detailed in Parts 3 and 4, upcoming) contributed to such instances, and sardars had to pay owners the wages advanced to absconding workers for the balance period.

Thus, sardars who were singed by the vagaries of the trade outnumbered those who made it and stayed.

“He Threatened He Would Find Me And Kill Me”

Gaurav Bhoi’s uncle Omkar Kharsil was a good example of a sardar who didn’t make it big.

Kharsil worked as a brick moulder at various sites in Telangana for 16 years, from the age of eight, before branching out as a sardar in 2012.

“I knew how to read, write and calculate, and used to maintain the accounts for 20-30 fellow workers when I worked at the kiln,” he said. He also stayed back for two years during the off-season months, loading and delivering bricks and doing other work. “The owner trusted me and gave me Rs 1 lakh.”

His trade flourished for six years, when he supplied 20-30 brick moulders, all from Ainlabhata, to a kiln owner in Telangana’s Peddapalli district. He constructed a spacious single-storey house in the village, bought a sedan, some land and gold, and got married.

In 2017, the owner doubled his requirement for labour shortly before the start of the season, taking the total number to 60. Kharsil sourced 30 workers from other villages, but after working in Peddapalli for a few days, they fled.

Furious, the seth asked Kharsil to return the Rs 9 lakh advanced to these 30 workers. “I didn’t know what to do. I pleaded with him. I tried calling the workers. I looked for them in their villages,” he said. “But I could not find them anywhere.”

He sold off his car and most of the land and gold he had acquired to repay a few lakhs to the owner, then changed his mobile number, and quit the trade.

A few years later, he began supplying labour to the construction sector, where no advances were involved and the income was decent, though not as much as earlier.

“Even now, when someone from neighbouring villages goes to work at the Peddapalli owner’s factory, he issues threats, saying if I do not return the money, he will kill me wherever he finds me,” said Kharsil, who was still waiting to buy a new car.

Kantabanji: The Hub Of Labour Trafficking

When poor villagers from the KBK region began migrating to brick kilns in large numbers in the 1980s, Kantabanji was the only railway station with a train link to south India. This played a crucial role in the sleepy town’s transformation into a hub of labour migration and trafficking.

Shopkeepers and vendors who owned stalls outside the railway station, including the locally well-known Makaru and Dasrath, comprised a large chunk of the first crop of sardars. Members of the local elite, including Muslims/Pathans and those with political connections, were the other major chunk.

For instance, one prominent sardar was known to have worked closely with a politician who ran a money-lending business in the 1980s and was later elected to the state legislature.

Most early sardars lived in and around Kantabanji, and travelled to Hyderabad, Visakhapatnam and other places in Andhra Pradesh to strike their first deals with kiln owners.

Kantabanji’s first hotel, Shree Annapurna Lodge, now a four-storey establishment with rooms stacked along narrow corridors and balconies, commenced operations in 1982 with six rooms. Its main clients were kiln owners who visited the town after every monsoon to meet sardars and make payments in cash for recruiting stipulated numbers of pathris—units of three to five workers, generally from the same family.

Soon, new lodges and hotels opened their doors. A network of specialised agents who handled the ticketing and transportation of migrant families by train took shape; many agents also recruited and supplied labourers to brick kilns. Traders in town set up thriving businesses loaning money to sardars, especially in the off-season, at 16%-18% per year. Policemen and journalists reportedly extracted bribes from sardars when they intercepted migrant families en route.

The number of sardars in the KBK region grew exponentially in later decades, keeping pace with the increase in distress migration from the region, said locals. Many were Dalits who started off as brick moulders. Many lived in villages far away from Kantabanji, and closer to new railway stations such as Nuapada, Harishankar Road and Nabarangpur.

The areas around these stations became new hubs of labour migration and trafficking, with their own set of hotels and lodges, transport agents, moneylenders, and policemen who extracted bribes.

A Kantabanji Police Raid Yields Rs 58 Lakh Cash

At the start of the 2022-23 migration cycle, an unusual incident in Kantabanji, the hub of labour migration and trafficking, provided further evidence of the clout that kiln owners exercise in the region.

On 15 September, Hrushikesh Meher, sub-divisional police officer of Kantabanji, addressed a press conference attended by more than 30 journalists, including some from neighbouring towns Patnagarh and Khariar.

Meher sat behind a table stacked with bundles of currency notes and mobile phones. Seven men, black hoods over their heads, were positioned behind the table.

A team led by him had raided the Shree Annapurna Lodge the previous night, Meher said. They had arrested seven men from Telangana who had been gambling in room numbers five and seven.

Rs 58,52,250 was seized in cash, besides playing cards, mobile phones and SIM cards, all displayed on the table.

The gathered journalists immediately wanted to know if the accused were kiln owners, and if the cash was meant to be handed over to sardars. “You will get to know everything in due course,” was all Meher would say.

Local reporters were flummoxed—it was highly unusual for the police to raid and arrest kiln owners. Intense speculation followed, about whether disgruntled sardars or rival lobbies were behind the operation.

One reporter claimed the cash seized was being under-reported and that the kiln owners were being branded gamblers for spurious reasons.

Five days later, on 20 September, Meher was transferred from Kantabanji and later placed under suspension for allegedly under-reporting cash seized during a police operation. Reports in the local media said an additional Rs 13 lakh seized from the lodge was found in a bag kept inside the Kantabanji police station.

A Post-Pandemic Crackdown Has Been Ineffective

The mass exodus of migrant workers during the Covid-19 pandemic and lockdowns in 2020 and 2021 forced governments and policy makers to take steps to address migrants’ problems and concerns.

In Odisha, the state government initiated its State Action Plan for Safety and Welfare of Inter-State Migrant Workers, which included promoting safe and informed migration, tracking of migrant workers at the panchayat level, and enforcement of the ISMWA.

The police also set up check posts around Kantabanji and other major hubs of trafficking, and registered cases against sardars under sections of law pertaining to human trafficking.

Anecdotal accounts indicated that the post-Covid period saw a spike in trafficking cases, a likely outcome of the crackdown.

Most of these cases were weak and unlikely to result in convictions, police officials told Article 14.

“The cases are all based on statements of migrant families, who either turn hostile in court or are unable to attend hearings because they work in other states for most of the year,” said Ramakant Sahoo, officer in charge of the Khaprakhol police station in Bolangir district.

Sardars also swiftly shifted 20% of the migrant labourers being sent to the kilns to road transport instead of rail, they told Article 14.

“Movement by road started in a major way during the Covid-19 period, when trains were not running and there was heavy police vigil at railway stations and bus stands. Roads were a safe bet because police presence was less, especially if major junctions could be avoided,” said Krishna, a driver with a Kantabanji-based travel agency who ferried migrant families to Hyderabad and other places in Telangana several times in 2020 and 2021.

Cars, pick-up vans and buses were pressed into service in large numbers during this period to transport migrant families to destination states. Bus services were also started between Sinapali in Nuapada district and Hyderabad in Telangana, where a majority of the migrants were employed.

The route was now serviced by three bus operators, of which only one was registered, said locals. Tickets for buses serviced by this operator were available on online platforms like Redbus.

“The buses are owned by sardars, and the passengers are mostly poor, unregistered villagers from Nuapada and neighbouring districts,” said Ajit Panda, a journalist based in Khariar.

“The registered operator has a licence for one bus, but is operating three buses. All this is happening with the connivance of police and government officials, who are paid handsome bribes,” he added.

Journey Fraught With Risks, Hardship

Meanwhile, for most migrant families who travelled to destination states by train, in unreserved compartments, the conditions of the journey remained just as exacting as pre-pandemic. The case of the Bhois was no different.

The compartment they were herded into at Kantabanji was already packed, with passengers far exceeding the sanctioned seating capacity of 80.

Aurav and Bhagyawati Bhoi managed to crawl on to shelves meant for luggage, where several others were already seated, whereas Gaurav and Chitrasen Bhoi found a spot near the door.

The Korba-Visakhapatnam Link Express reached its destination on 13 December, around 7 am. No minder was accompanying the Bhois as they had not taken an advance payment. They waited at the station for nearly 12 hours, watching out constantly for police, apprehending being detained and implicated in cases.

Around 7 pm on 13 December, they boarded a train to Secunderabad.

“This train was as packed as the last one, but we were relieved since there was little possibility of the police catching us any more,” said Chitrasen Bhoi.

His relief was well-founded. Several kiln owners, sardars and sources in the police and administration in Telangana told Article 14 that police did not stop or harass migrant workers.

Neither Gaurav nor Chitrasen Bhoi paid attention to the name or number of the train, though, for they were preoccupied with planning a risky, but well-thought-out move.

The sardar had instructed the Bhois to report for work at Rajni seth’s factory, located on the outskirts of Hyderabad. But villagers in Ainlabhata who worked there earlier had warned them that the owner assaulted workers on the slightest pretext and often delayed payments.

On the other hand, D Venkateswarlu, at whose factory the Bhois had worked in the previous year, was a demanding taskmaster, prone to abusing and hitting those who did not meet targets. He was prompt and fair with payments, however, and the Bhois had impressed him enough to get his phone number.

So, after the train pulled into Secunderabad station on 14 December, around noon, the Bhois found a quiet spot on the platform, and Gaurav implemented the plan.

“I called the owner and told him we wanted to work at his factory, and requested him to speak to our sardar. He called back after a few minutes, and asked us to go there,” said Gaurav.

They took a cab from the station to the factory in Raviryal village near the Wonderla amusement park, and reached there as dusk was falling. The fare of Rs 1,400 was paid by the munshi, or manager, Sitaram, also an Odia, whom they knew beforehand.

At the worksite, they were greeted by heaps of raw materials on a flat, bare expanse of six acres. This was the place that would be their home for the next six months.

(Aritra Bhattacharya is an independent journalist and researcher based in Kolkata. Saurabh Kumar is a researcher, multimedia journalist and documentary film-maker based in Mumbai. The authors thank Sushant Panigrahy, an anti-trafficking activist from Odisha’s Bolangir district, for his help in reporting this story.)

* Name masked to protect the Bhois from potential reprisals.

This is the second of a four-part series. Here is part 1, part 3 and part 4.

Next: No Housing, No Toilets, No Medical Care, No Schooling: Bonded Labourers Face Assault, Sexual Violence, Denial Of Rights

Get exclusive access to new databases, expert analyses, weekly newsletters, book excerpts and new ideas on democracy, law and society in India. Subscribe to Article 14.