Dehradun: It was his wedding anniversary but instead of going out with his wife as planned, this young bank employee stood on a railway track in Gujarat.

It was just hours since his senior at the bank, one of the country’s largest national banks, had threatened to ruin his career.

“I’m not able to bear it any more… I’ve lost the will to live,” he told a superior officer on the phone. Voice quivering, he said he was standing on the track.

Article 14 has heard this call recording and an earlier call in which the senior lambasted the employee. It was midnight when the young officer relented and went home, said a bank staffers’ union leader who was able to get through to him on the phone that night.

The incident took place on 26 April 2024, one of several instances from banks and branches across India.

A chief manager of Union Bank in Gujarat hanged himself in February 2024, his suicide note blaming the work culture and workload. “The staff should not be assigned impossible targets and terrorised” his note said, “or else others too like me would be driven to suicide.”

Two weeks later, a branch manager of UCO Bank in Tamil Nadu ended his life, reportedly due to work-related pressures. He left behind a year-old daughter. Five instances of suicide by bank employees came to light in a single week in August 2023, two in April 2024 and one in May 2024, when a branch manager of Union Bank in Tamil Nadu ended his life, reportedly owing to stress and depression regarding high targets.

By one estimate, work woes have pushed at least 500 bank employees in India to suicide over the past decade. Some left damning letters, citing harassment and abuse by seniors. In some instances, the family of the deceased filed cases of abetment to suicide against seniors, some of whom were arrested (see here, here, here).

Unionists said managers ensure that banks meet business targets by any means available, leaving employees at the mercy of senior management.

Customers are not impervious to these internal dynamics. A research report in 2013 estimated that the fraudulent sales of insurance products by banks between 2004 and 2012 had robbed banks’ customers of Rs 1.5 lakh crore. A recent investigative report by The Reporters’ Collective showed that this organised loot is still prevalent.

This is the second of a two-part investigation into the impact of such fraudulent practices on customers and the banking system. Part 1 (here) detailed how banks have inflated data on account of being under pressure to present a rosy picture of deposits, loan recovery, and digital transactions.

Over a year and a half, more than two dozen bank employees told Article 14 about multiple such scams, some with evidence (here, here). They described how managers enjoy a free rein and render checks and balances ineffective. Article 14 also went through more than a hundred letters sent by employees and their unions to their management about these circumstances. Some letters bore actionable intelligence against corrupt executives accused of fostering malpractices or accepting kickbacks.

These interviews and letters point to a systemic issue plaguing the country’s banks. Our investigation found that many banks’ work culture involves the subjugation and disempowerment of employees, resulting in normalisation of frauds.

Neither the RBI nor the banks mentioned in this report commented on the allegations of employee abuse and frauds. Article 14 emailed them a detailed questionnaire in mid-May and a reminder on 10 June, but the mails remained unanswered.

Occupational Hazards

Grievances that came up most frequently in employees’ interviews and unions’ letters were harassment, humiliation, torture, autocracy, dictatorship, inhuman behaviour, etc. Another recurring theme was the fallout of these—lack of dignity, no work-life balance, and health woes including depression, anxiety, high blood pressure and trauma.

Another common theme was managers’ bragging that they could get away with this behaviour owing to their close connections with the top management. One employee alleged in his letter that his zonal manager actually threatened to kill him when he sought to go home at 7 pm.

In September 2022, Bank of Baroda (BoB) employees in Rajasthan were up in arms against a regional manager. Unions’ complaints quoted him as saying that driving employees to suicide or resignation was his “achievement”. He reportedly said, “Even if some people die, the bank won’t be affected.”

Unions’ letters cited many examples of his behaviour. He reportedly summoned a branch head back to work after the demise of his mother, referring to the departed parent as a “buddhi” (old hag). The unions’ letters accused him of holding employees hostage till 1 am in office, and debiting customers’ accounts for insurance schemes they had not sought or consented to.

To unions’ demand that the official be reined in, the bank instead announced that it would go after the employees who had raised the matter on social media. The same day, the bank declared on X that the matter was amicably resolved.

It was anything but. Five days later, more than a thousand BoB employees from across Rajasthan staged a demonstration outside the bank’s Jaipur office, but to no avail. Those leading the protest were transferred to remote locations in the next transfer season.

Six months after the protest, the bank was certified as a Great Place to Work, a rating provided by Great Place to Work Institute, a global research, consulting, and training firm, for its “positive work environment”.

It was not a rare, or even uncommon, case.

Three months after the State Bank of India (SBI), India’s largest government bank, was declared 2023’s most preferred workplace in the banking sector, an honour announced by event management firm Team Marksmen, the bank’s employees in Chandigarh complained to their union that a deputy general manager not only dared employees to resign but also mentioned suicide. “He expressed a firm belief in humiliation to a degree that is unimaginable and unacceptable,” the letter to the SBI Officers' Association (Chandigarh Circle) noted.

Around the same time, an SBI union in Ahmedabad expressed concern in a letter to the bank’s local administrative office that an employee was under extreme stress and fear, and could resort to self-harm after an assistant general manager reportedly hurled abuses and lunged at him. A month later, a BoB employee from Chandigarh wrote to the management that the trauma and humiliation he had been facing at the hands of his regional manager had made him suicidal, and that the latter must be held responsible if he ended his life.

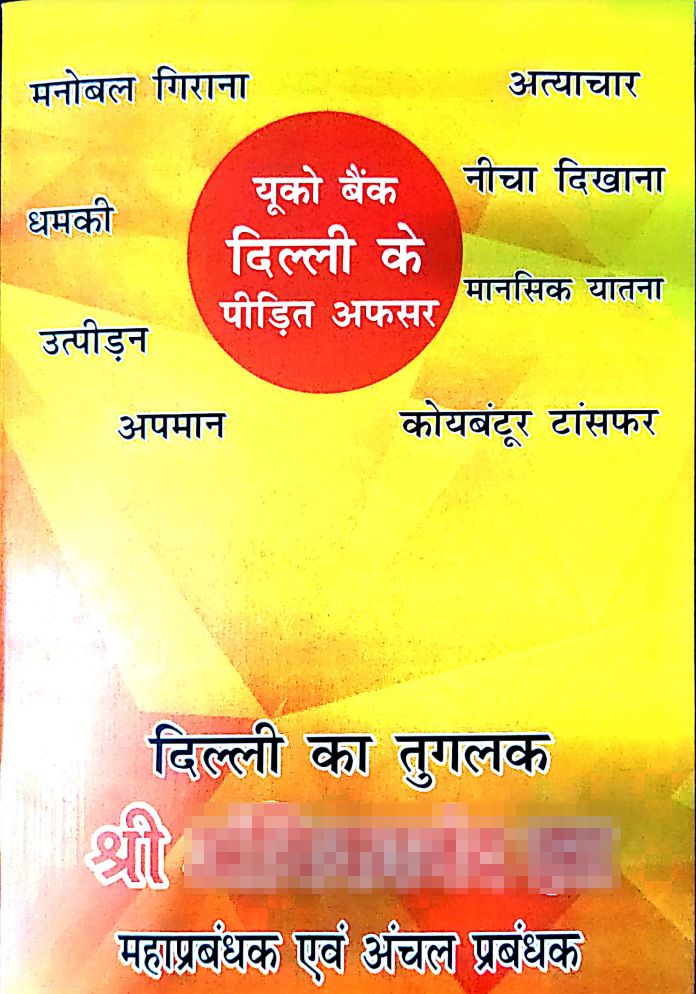

Such was the frustration of UCO Bank’s Delhi zone employees with their zonal manager in 2023 that they brought out a 41-page booklet chronicling his behaviour and asking the management to intervene.

Unions’ letters from banks across the country are replete with troubling anecdotes.

When an employee of Aryavart Bank in Uttar Pradesh (UP) sought leave on account of his brother’s death, his regional manager told him on WhatsApp, “Your branch business position is not good. Leave can’t be permitted.” Also in UP, a BoB employee’s sanctioned leave in view of his grandmother’s demise was ordered to be cancelled, with a senior allegedly saying, “Nani-dadi marti rahengi. Usko loss of pay karo.” (Grandmothers will keep dying. Dock his pay.)

Another BoB employee in UP was reportedly denied leave to attend to his pregnant wife when she went into labour. Neighbours took her to hospital for childbirth, said the All India Bank of Baroda Officers’ Association in a letter to the respective zonal manager. Likewise, a letter by BoB employees to their zonal head in Gujarat alleged that a manager told an employee that his wife giving birth was a “normal process”, asking why he had sought a leave for the event.

One letter to the bank’s head office alleged that in Canara Bank, regional offices in the Pune circle directed employees to work on all public holidays for six months starting August 2022, that too without any compensatory off, to generate business.

Promotion And Power Play

Ashish Mishra, general secretary of the We Bankers Association, a trade union of bank employees based in Uttar Pradesh, explained that when managers perform well in business campaigns, they gain an edge over others in the race for promotion. Hence, he said, managers don’t think twice before threatening their subordinates if they deem that is an effective way to get the job done.

This pressure begets frauds, many unions’ letters said.

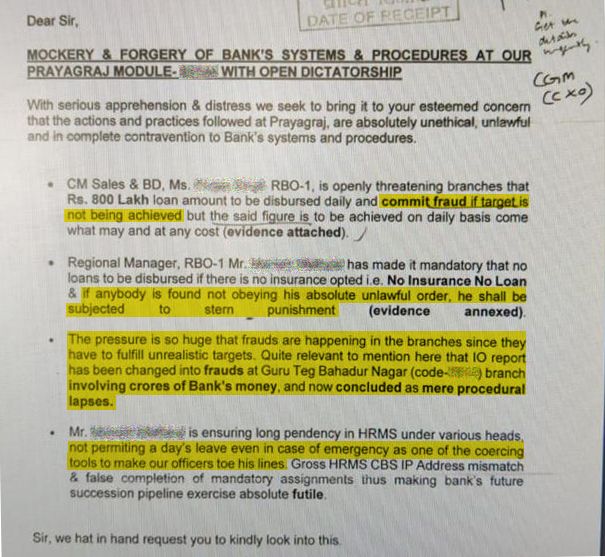

One letter from employees of a large government bank to the management said that a chief manager asked branch heads to “commit fraud” if the target was not achieved. “The pressure is so huge that frauds are happening in the branches since they have to fulfil unrealistic targets,” the September 2022 letter said, adding that even internal investigation reports had covered up these scams, downplaying them as procedural lapses.

“In the evening, we come back and wonder what misdeed we’ll be required to do tomorrow,” the branch head of a regional rural bank told Article 14 over the phone after spilling the beans about some frauds.

Those who do not toe the line do face consequences. One young officer said his manager threatened to transfer him to a village near the Bangladesh border for refusing to execute illegal tasks. Another bank transferred an officer to a village near the Pakistan border for speaking up against an abusive manager. Article 14 has spoken with many such employees who were given such ‘punishment postings’.

Mishra said that while banks do have the right to transfer anybody anywhere at any time in case of an administrative exigency, this right has been misused as a coercive tool. He said managers on a power trip weaponise transfers to cut troublemakers to size and bully others into submission.

A Bank of India employee, Mishra himself had been transferred in March 2022 after questioning a malpractice. He challenged his transfer in court, which ruled in his favour in June 2023 and asked that three senior bank officials be booked for transferring him in violation of labour laws.

In June 2023, We Bankers Association notched up another legal victory when the Supreme Court overturned the suspension of the union’s national convenor Kamlesh Chaturvedi. His employer Punjab National Bank (PNB) had suspended him a day before his retirement in 2016, depriving him of his pension and gratuity.

Chaturvedi told Article 14 over the phone that the management wanted to make an example of him and had offered to revoke his suspension if he gave a written apology and a commitment to give up his trade union activities. He refused.

For the next seven years, Chaturvedi represented himself, first in the labour tribunal, then in the Allahabad high court and finally in the Supreme Court as PNB lost at each stage but challenged the verdict.

Chaturvedi won in the Supreme Court even though PNB roped in Solicitor General of India Tushar Mehta to argue its case. “They brought in an elephant for a battle with an ant,” the union activist said.

A Rajasthan high court order in June 2023 was another setback to PNB, overturning the bank’s decision to compulsorily retire an employee. The court deemed the punishment “harsh”.

Mishra said that in a bid to deny employees justice, prolong their misery, break their spirit, and make an example of them, banks abuse legal remedies and their spending power. He said banks often fight even baseless cases tooth and nail, losing comprehensively but challenging the verdict in front of a larger bench or a higher court nonetheless, engaging top lawyers in high courts and the Supreme Court, paying them lakhs of rupees in fees. “Banks waste the public’s money [in frivolous litigation]. If this money is not wasted, it will go to the shareholders as dividend, it will add to the bank’s profit,” MIshra said. He added that banks would go “to any extent” to act against those who complain in official forums.

Under the Right To Information (RTI) Act, 2005, We Bankers Association asked Bank of India in 2020 how much it had spent on lawyers and litigation. The bank refused to disclose the details, an order that We Bankers Association challenged. The bank’s contention was that collecting and compiling the information would “disproportionately divert the resources of the public authority”.

Eventually, the Central Information Commission imposed a penalty of Rs 5,000 each on two bank officials in June 2023, holding them guilty of deliberate and mala fide negligence in providing the information. The bank has now challenged this decision in the Allahabad high court.

A member of We Bankers Association’s RTI cell, Chayan Ghosh Chowdhury, closely pursued the case regarding BoI’s litigation expenses. He tracked government banks’ practice of entangling their employees in extended and frivolous litigation for standing up to misbehaviour and/or unethical acts. Over a phone call with Article 14, he dubbed this practice “white-collar terrorism”.

In May 2022, Chowdhury sent a letter to the then union law minister Kiran Rijiju, seeking to draw his attention to this problem. The letter cited telling observations by high courts, the Supreme Court, and the Law Commission of India, showing that the judiciary was well aware that banks readily go to courts “due to ego clash or [to] save officers’ skin” and that such “frivolous litigation clogs the wheels of justice”.

Systematically Silenced

As per law, all banks have a whistleblower policy that includes a platform for employees to report misconduct. On paper, these policies are comprehensive and guarantee a fair probe. However, employees say the mechanism has been ineffective for the most part.

In Punjab & Sind Bank Vs Durgesh Kunwar, a Supreme Court bench comprising Chief Justice of India DY Chandrachud in February 2020 found the bank guilty of transferring Kunwar unfairly, an act “vitiated by malafides” in retaliation to her reports of corruption in her branch and allegations of sexual harassment.

The general manager accused of harassing her was promoted as executive director in March 2024.

We Bankers Association’s Mishra said there have been instances in which complaints under the whistleblower policy were assigned to the very officers they were against.

“If you lodge a complaint under the whistleblower policy, you’ll be targeted under one or the other pretext,” he said.

A conversation between a regional manager of SBI and a branch employee in December 2022 shows how filing even a trivial complaint may backfire. This employee took to the employee grievance portal to complain about his pending leave request. This angered his senior so much that on a call, whose recording Article 14 has heard, the latter threatened to ruin his career.

“Barbaad ho jaaoge. Mitti mein mil jaaoge. ‘Officer with doubtful integrity’ ka board laga denge… Uske liye koi evidence ki zaroorat nahi hai,” the regional manager said. (You’ll be ruined, turn to dust. We shall tag you as an ‘officer with doubtful integrity’... No evidence is needed for that.)

Employees who spoke to Article 14 did not have faith in the auditing process either. All branches undergo an internal audit every 6, 12 or 18 months, by internal audit teams comprising officials posted in banks’ higher offices. Ordinarily, an audit should be able to spot, for example, that account holders’ consent forms do not exist for various schemes they were enrolled into.

One employee said auditors at his branch in 2022 glossed over plentiful evidence of wrongdoings and were treated to whiskey every evening.

An officer who is a member of his bank’s auditing team disagreed with this characterisation. He said auditors would report a misdeed if they spot it, and then the erring branch would face an investigation. He conceded, however, that internal auditing is not always thorough. He said the scope of auditing is exhaustive while time assigned for the work is limited.

The Reserve Bank of India (RBI), the apex body that regulates banks in the country, is aware of this problem. In a speech in March 2022, RBI’s deputy governor M K Jain acknowledged that banks’ assurance functions suffer from “common weaknesses” including sub-par compliance; failure to detect and report non-compliance; internal audit’s inability to capture irregularities; non-coverage of certain areas under the scope of audit; and lack of accountability.

Monkey Business

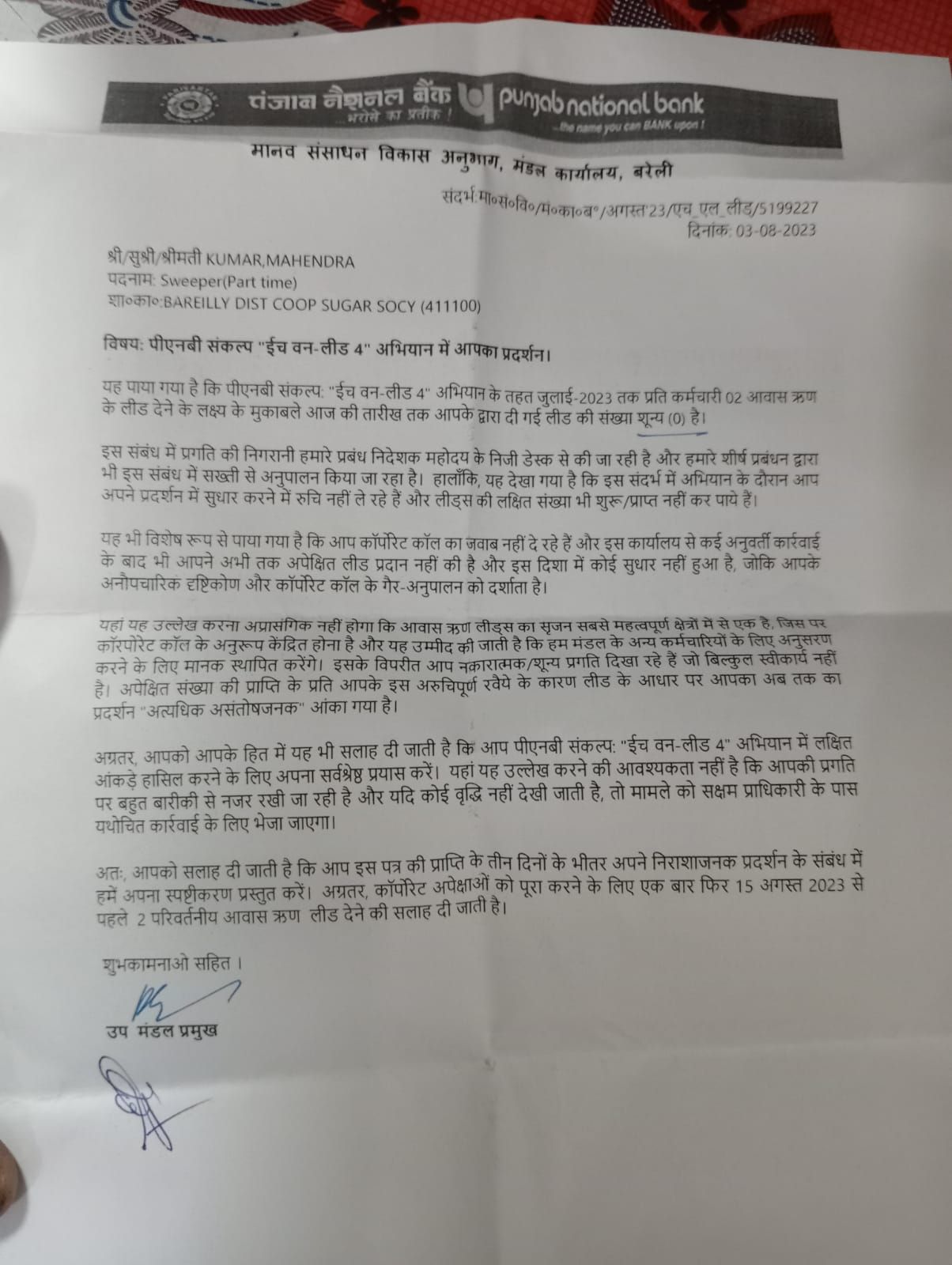

In August 2023, the country’s third-largest public-sector lender, Punjab National Bank (PNB), issued a show-cause notice to a part-time sweeper of a branch for not generating leads for housing loans.

The bank’s circle office in Bareilly, Uttar Pradesh, admonished the sweeper in a full-page letter typed in Hindi for not meeting “corporate expectations” and asked him to explain in writing his disinterest in business generation.

The previous year, Rajasthan Marudhara Gramin Bank reportedly forced its temporary peons to sell two insurance policies each, failing which they were asked to buy policies themselves, as per a letter by the bank employees’ union to a regional manager.

Screenshots and graphics circulated in employees’ WhatsApp groups indicated how business targets were at times set arbitrarily. On the 59th birthday of an executive, a zonal manager ordered his juniors to sell 59 policies each of various types, for a “birthday bouquet”.

An executive once covered 52 km on a bicycle. A manager soon called for selling insurance policies worth Rs 52 lakh “as a token of our love”. Such instances are commonplace. Targets such as these, bank employees said, lead to unethical practices and forced selling of policies.

These dynamics in India’s banks tick all the boxes of the ‘fraud triangle’, a concept used by anti-fraud professionals to predict the likelihood of frauds. According to US-based non-profit National Whistleblower Center, three factors indicate a high risk of fraud: motivation (managers’ pursuit of promotion), opportunity (failure of internal control mechanisms), and rationalisation (perception that seniors condone frauds or that frauds are common in the industry).

Second of a two-part series. You can read the first part here.

(Hemant Gairola is an independent journalist based in Dehradun.)

Get exclusive access to new databases, expert analyses, weekly newsletters, book excerpts and new ideas on democracy, law and society in India. Subscribe to Article 14.