Ahmedabad: Pravinbhai Ghariyal, 46, sat in his living room looking at the rain in his one-bedroom room home in Ahmedabad’s working-class neighbourhood of Vastrapur. Around him mattresses were stacked on the side, electronics and documents were stored in a cupboard and buckets were scattered around to collect water from a leaking roof.

A few years ago, his family was comfortable, both he and his wife worked in housekeeping, and they earned enough to provide for their family of seven, four children and his mother. Today, the family is in debt, and there is no money to even buy a tarpaulin sheet to cover their leaking roof.

The Ghariyals’ lives changed in 2021, when Pravinbhai’s wife, Manjulaben, suffered a stroke. She was rushed to Phoenix Hospital, a private institution in Ahmedabad, where she stayed in an intensive-care unit for a few days.

The hospital asked for a deposit of Rs 60,000, and the Ghariyals spent Rs 20,000 every day for medicines. By the end of 10 days in the hospital, Pravinbhai had spent Rs 300,000.

Since the Ghariyals did not have that much money, Pravinbhai borrowed it from a local moneylender keeping the papers of his house as collateral at an interest rate of 30% per annum. Manjulaben recovered from the stroke, but she can no longer work because her right side is still weak. Pravinbhai said he felt the pressure of repaying the loan, but all he can manage is the interest—Rs 5,000 per month.

Now, Pravinbhai and his son Satish, 22, work in housekeeping, together earning between Rs 12-15,000 per month, which, after paying the interest and spending on Manjulaben’s medicines—Rs 4,000 per month—leaves very little to live on.

Pravinbhai said he struggled to buy uniforms or books for his younger twin children, Prachi and Prateek, 14. He gets by through the kindness of acquaintances, one of whom paid for his son’s uniform.

“I asked for an advance of Rs. 200 from my manager today, and I will now buy oil, wheat and dal from this,” said Pravinbhai. “When I struggle to buy groceries at home, where do I get clothes for them?”

Given his inability to pay, the money lender has waived the interest, so he has to pay only the principal amount. Still, it will take Ghariyal’s family about 5 years to repay their debt.

Their newly penurious situation has plunged the Ghariyals into poverty, among 60 million Indians who fall into or fall back into poverty because of “catastrophic healthcare expenses”— more than 10% of household income—as the government and health economists describe the term.

Scheme Meant To Stop The Fall Into Poverty

When Prime Minister Narendra Modi launched the Pradhan Mantri Jan Arogya Yojana (PMJAY) or the Prime Minister’s People’s Health Programme, one of the aims of this health insurance scheme was to prevent these catastrophic expenditures that, as its website says, “push 60 million Indians in poverty every year”, or as much as the population of South Africa.

Pravinbhai said he did not know about PMJAY’s insurance benefits, that his family could have benefitted from cashless hospitalisation up to Rs 500,000. Asked why he did not go to a government hospital, he said, “It was an emergency, and I didn’t want to go to the government hospital and face delays”.

The Failure Of Indian Public Health Facilities

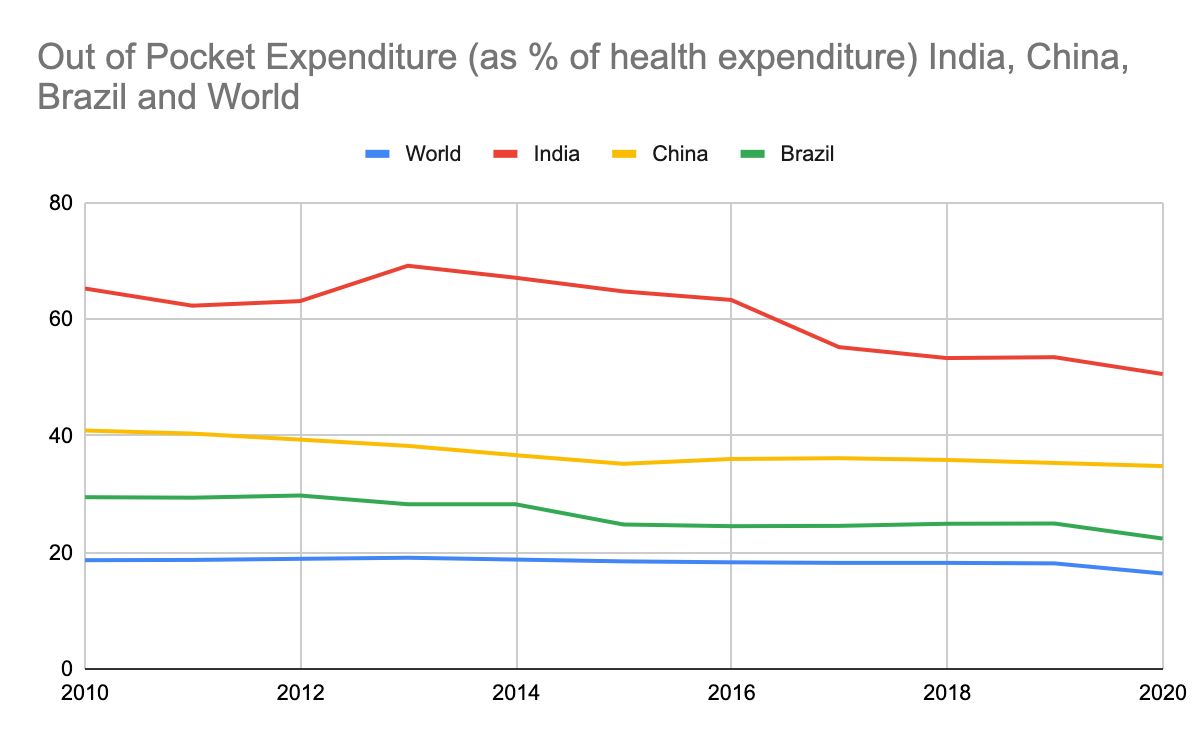

With out-of-pocket (OOP) expenditure down from 69% of current health expenditure in 2013 to 50.5% in 2020, the government has claimed that PMJAY has been largely successful and “saved crores of families” from catastrophic expenditure. But there are no data to support that claim, health economists told Article 14.

Recent studies (here, here and here) have shown PMJAY is not yet meeting the needs of India’s most marginalised and exposes beneficiaries to financial exploitation by the private hospitals. The scheme does not cover outpatient costs, which include medicines that make up two thirds of health expenditure.

Unless the government invests in public health care, regulates private healthcare and enables affordable medicines, experts said, PMJAY will not help the majority of the people it is meant to and stem the plunge into poverty it is meant to prevent.

Govt Bets On Health Insurance Instead Of Healthcare

The Indian government spends 1.35% of its gross domestic product (GDP) on healthcare, among the lowest in the world, while low- and middle-income countries spend around 6% GDP on public healthcare. So, it isn’t surprising, said experts, that Indians spent more money on private healthcare than most others worldwide.

In 2018, Modi’s government launched the Ayushman Bharat scheme to achieve its vision of universal health coverage using health insurance for the poor and the development of 150,000 Health and Wellness Centres to deliver primary care.

Currently, 146.5 million are families covered by PMJAY, 66% of eligible families. That figure goes up to 75% of the population after factoring in existing government health-insurance schemes, state and union.

Modi’s home state, Gujarat, is among the top five states by number of PMJAY enrolments, with all eligible families covered—supposedly.

What The 2023 Budget For PMJAY Reveals

In Ahmedabad, Gujarat’s largest city with 7 million people, many families we interviewed had not heard of PMJAY.

The enrollment centre for PMJAY is next to the reception of the emergency medicine department at the Ahmedabad Civil Hospital, but we found very few opting for it. Daily PMJAY registrations in a hospital with over 3,200 beds was 50.

“Yes, the scheme is being underutilised here, there is scope for improvement,” said chief medical officer of the hospital’s insurance cell, Dr Rajesh Patel. He said that till 2022, the enrollment rate was only 10 a day, possibly because of lack of awareness or because people knew treatment would be free in a government hospital.

The 2023-24 union budget set aside Rs 7,200 crore for PMJAY, a 12% increase over the previous year but nine to 22 times lower than a 15th Finance commission estimate of the money—Rs 66,000 crore to Rs. 160,000 crore—required in 2023 if eligible families in India utilised the scheme.

Whether PMJAY, in its fifth year, has been successful in reducing out-of-pocket expenses is not clear. Indranil Mukhopadhyay, health economist and a public policy professor at Jindal School of Government and Public Policy in Sonipat, Haryana, said saying anything before a National Sample Survey Organisation(NSSO) expenditure survey due in the next six to eight months would be “problematic”.

Yet, the government claimed in July 2023 that PMJAY saved Rs 66,326 crores in out of pocket expenditures through 5.39 crore hospitalisations.

Mukhopadyay said the PMJAY website showed “selective data '', there was “no transparency or independent evaluations”, making a verdict on the programme’s success in reducing out-of-pocket expenses difficult.

For instance, the dashboard of National Health Authority, that implements PMJAY, only had information about the PMJAY cards issued, hospitals empanelled but doesn’t give any more detailed information.

Not Learning From The Past

In 2008, India’s previous Congress-run government launched the Rashtriya Swasthya Bima Yojana (RSBY), providing insurance cover of Rs 30,000 for inpatient care to families below the poverty line (BPL).

Despite covering over 36 million BPL families, studies showed (here and here) that RSBY did not reduce catastrophic health expenditure because of limited coverage and medicines, diagnostics and outpatient care not covered by the scheme. Some studies showed that out-of-pocket expenditure had increased, since healthcare providers convinced families to use services not covered under the scheme.

About 19.1% of households in urban India and 14.1% in rural India reported any form of health insurance, according to the estimates of the NSSO in 2017-18, the latest national data on healthcare expenditure. The National Family Health Survey 2019-21, the latest available data, showed that this figure had increased to 41%.

Yet, the problems with RSBY continue to plague PMJAY, even though the programme launched by the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) government improved insurance coverage and addressed some of its deficiencies--more beneficiaries insured, more medical procedures covered, wider hospital network and better IT and governance system.

The Poor Benefit The Least

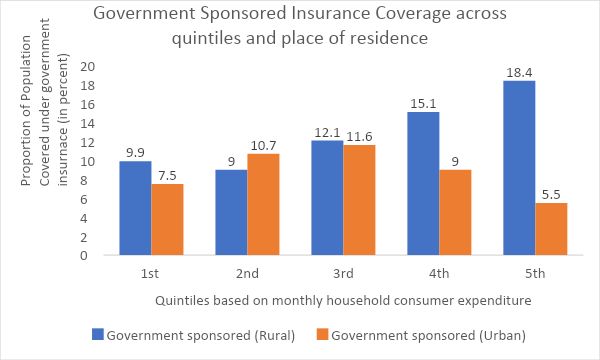

Government-sponsored health-insurance schemes have the highest coverage among the “highest quintile” or the richest 20% in rural India, said Khushboo Balani, an Indian Institute of Technology (Bombay) doctoral student who specialises in health finance, after analysing 2017-18 NSSO data.

“The poorest 40%, have the least amount of coverage,” said Balani. This 40% is the target population of PMJAY, which means those who need it most may not have access to it.

Health Insurance By Place Of Residence

Other studies have found similar trends. In June 2023, a study published in Lancet Regional Health investigated equity in PMJAY’s utilisation across geography, sex, age and social groups and found that wealthier states, such as Kerala and Himachal Pradesh, used the programme more than poorer states with higher disease burdens, such Bihar, Madhya Pradesh, Uttar Pradesh and Assam.

There are more men enrolled than women in PMJAY, as are those 19-50 years. Fewer scheduled castes (SCs) and scheduled tribes (STs), who are among India’s poorest people, sign on, compared to other castes, largely because SCs and STs tend to use public health facilities.

Dalit families were 4% and ST families 1.3% of all hospitalisations in private hospitals under PMJAY between 2019 and 2021, according to this analysis by the website News Click.

For context, 63% of all hospitalisations under PMJAY over that period were in private-sector facilities. According to the University of Oxford’s multidimensional poverty index 2018, the latest caste aggregated available data, 33% of Dalits and 50% of STs are poor.

“Many of the underprivileged tribal and rural patients do not have PMJAY cards because some of them do not even have Aadhaar cards,” said Dhiren Modi, director of community health of an NGO called Sewa Rural, which runs the 250-bed Kasturba Hospital in Jhagadia in south Gujarat, where the population is 32% tribal.

Despite free treatment and medicines in government hospitals, patients are often referred out of the public health system because specialists are not available, said Modi. “When they are seeking treatment in a private hospital, most patients do not have active PMJAY cards with them,” he said.

Cost Of Medicines Not Covered By PMJAY

Medicines contribute to higher out-of-pocket expenses in India than many other countries.

Despite being one of the largest suppliers of affordable generics to the world, nearly two thirds or 70% of all out-of-pocket payments in India are because of medicines. Drug costs are estimated to account for 36.8% of total health expenditure in India. So, health insurance, which covers only inpatient costs, is of no use in reducing medicine cost and, thus, catastrophic health expenditure.

A 2018 study by Shaktivel Selvaraj and Habib Hasan Faroqui and Anup Karan from Public Health Foundation of India showed that 38 million households were pushed into poverty due to the cost of medicines alone in 2011-12. The study also noted that the share of medicines as part of out-of-pocket expenses increased by 70% between 1993 and 2004, one of the main reasons being the unavailability of free medicines in public hospitals, pushing people to private clinics and private pharmacies.

Such costs are set to increase, said experts, given the growing incidence of non-communicable diseases in India, such as diabetes, hypertension and cancer, which require more frequent follow-up with consultants and regular medications.

While the union government has launched a jan aushadhi scheme, formally called the Pradhan Mantri Bhartiya Janaushadhi Pariyojana (PMBJP) to provide affordable cheaper medicines, a 2022 study in two districts of Maharashtra showed many essential drugs were not included in the PMBJP drug list and half the essential drugs included were not available in the outlets surveyed.

Even after a growing rise in sales--more than Rs. 1000 crores this year, PMBJP still accounts for less than 1% of total pharmaceutical sales in the country.

High Out-Of-Pocket Expenditure Despite Insurance

That private hospitalisation leads to higher financial hardship is clear: households experienced four times higher catastrophic expenses (37%) in private hospitals as compared to public hospitals (10%) because of high out-of-pocket expenses, according to NSSO 2017-18.

Yet, 55% went to private healthcare facilities for inpatient care and 66% for outpatient care. Inadvertently, government-sponsored programmes also ended up sending patients to private sector hospitals because many are authorised—the formal term is “empanelled”—to care for such patients (for which they are reimbursed), where they often face out-of-pocket expenditure.

Balani, the IIT-Bombay PhD student, with Sarthak Gaurav and Arnab Jana, professors of Ashank Desai Policy Studies at the same institute, found that patients in states where 50% of the population was covered by government health insurance programmes, such as Chhattisgarh, Andhra Pradesh and Telangana, tend to use private health facilities more than those with lower rates of insurance.

Balani found that despite being covered by government-sponsored insurance, households in these states had a high rate of poverty after paying for healthcare. “These families may be going to private hospitals empanelled under the (insurance) scheme, but they still end up paying from their pocket when they find some services or procedures not covered,” said Balani.

In a 2020 paper, published as DAWN discussion paper, on the impact of publicly funded health insurance schemes— in this case PMJAY and the state’s own MSBY—on women in Chhattisgarh, public health researcher Sulakshana Nandi found that that women had to make out-of-pocket payments despite the schemes, many enduring harassment and abuse when they could not.

A more recent report, Sick Development, released in June 2023 by the charity Oxfam, found patients unable to use PMJAY cards in private hospitals. The authors interviewed five patients and their caregivers from Odisha and Chhattisgarh, signed on with PMJAY, who sought care in private hospitals.

They found three families blocked from using their cards altogether, one patient’s card was used only selectively and the one did not know whether or not his card had been used at all because his bill did not reveal that. In none of the cases were the caregivers given a valid reason why PMJAY cards were partially used or rejected. As a result, all the five families suffered catastrophic financial consequences and paid fees they should not have had to.

There is, thus, growing evidence that by encouraging greater use of for-profit providers, the insurance schemes are exposing poor and marginalised folk, especially women, to even greater risk of financial hardship.

“Government insurance is contributing to an ‘infrastructure inequality trap’, as higher utilisation and costs of private healthcare in urban areas are diverting ever greater proportions of public funding away from rural and the most under-served areas,” said the Oxfam report.

Private Healthcare Does Not Lead To Better Quality, Ethics

In 2021-22, 54% of all PMJAY claims were from the private sector, according to PMJAY’s annual report. While the average claim was Rs 9,045 in public hospitals, it was Rs. 13,730 in private facilities. Public health experts often cautioned (here, here and here) against this reliance on the private health care system to provide ethical and quality care when it is largely unregulated.

Over the years, private hospitals have prescribed unnecessary medical procedures when patients have health insurance coverage. There have been multiple investigations and studies, for instance, about unnecessary hysterectomies (surgical removal of uterus), conducted by private hospitals in Bihar, Rajasthan and Andhra Pradesh, under state schemes and RSBY for financial gain.

Since then there have been efforts to restrict hysterectomies in private hospitals. A 2020 analysis by the National Health Authority showed that almost 70% of all hysterectomies are conducted in the private sector and more than 75% of the claims are from the six states of Chhattisgarh, Uttar Pradesh, Jharkhand, Gujarat, Maharashtra and Karnataka; and 23% of hysterectomies were performed on women younger than 39 years.

Similarly, 29% of all deliveries under PMJAY are done through caesarean section, much higher than the World Health Organisation (WHO) ideal rate of caesarean section, which is between 10-15%. Further, 63% of caesarean sections under PMJAY are done in the private sector, while the majority of normal deliveries (78%) are done in the public sector, noted Sulakshana Nandi, in the DAWN discussion report we mentioned earlier.

In a 2023 paper published in the Journal of Economic Perspectives, economists Jishnu Das from Georgetown University and Quy-Toan Do from the World Bank, analysed the performance of publicly funded health insurance in low and middle income countries for 20 years and found that while these schemes increased financial protection and utilisation of medical services, they did not led to better health outcomes.

Some of the reasons cited by the authors are that health insurance schemes often led to unnecessary care and new sources of uncertainty because patients signed up with such schemes did not know if their insurance would be honoured or they would be correctly treated.

“Without regulating the private sector, it is very difficult for health insurance to improve health outcomes in those schemes that rely on private sector care,” Das told Article 14. “And yes, in India the insurance scheme has increased the engagement with the private sector without sufficient precaution. The specific problem we point to is how to price the care you receive from the private sector, without it leading to too much or too little care.”

Government Funds Diverted To Private Hospitals

Despite the fact that public hospitals cater to more vulnerable groups and women, the private sector has received a larger proportion of PMJAY funds. These funds could have been used to improve the public sector, public health, activists argued.

The June 2023 paper published in Lancet Regional Health, mentioned previously, explored this argument and found the government health expenditure had not increased in parallel to funds allocated to PMJAY. In 2019-20, as the overall health budget increased by 16.3% compared to the previous year, funds allocated to PMJAY increased by 166%, the paper noted.

The union government’s focus on an insurance model to reduce out-of-pocket expenditure without investing in public health facilities shows misplaced priorities, said Mukhopadhyay, the health economist from the Jindal School of Government and Public Policy.

“There is no evidence that PMJAY works,” said Mukhopadhyay. “The evidence we have shows that it is exclusionary and does not include the most marginalised sections of society.”

(Swagata Yadavar is an independent journalist based in Ahmedabad, writing on healthcare, gender and development.)

Get exclusive access to new databases, expert analyses, weekly newsletters, book excerpts and new ideas on democracy, law and society in India. Subscribe to Article 14.