New Delhi: The first of many stories that Nirmal Kumar Jain shared was the one where he shouted, “Atal ji, Atal ji, Atal ji, give me justice” from the gallery for viewers in Parliament on 19 April 2001, when Atal Bihari Vajpayee was the prime minister of India.

Recalling the incident, Jain told Article 14 that he would have jumped into the well of the house if security officers in the lower house of Parliament, the Lok Sabha, had not held him back. Now that he was 75 years old, his 46-year-old search for justice was far more muted, he said.

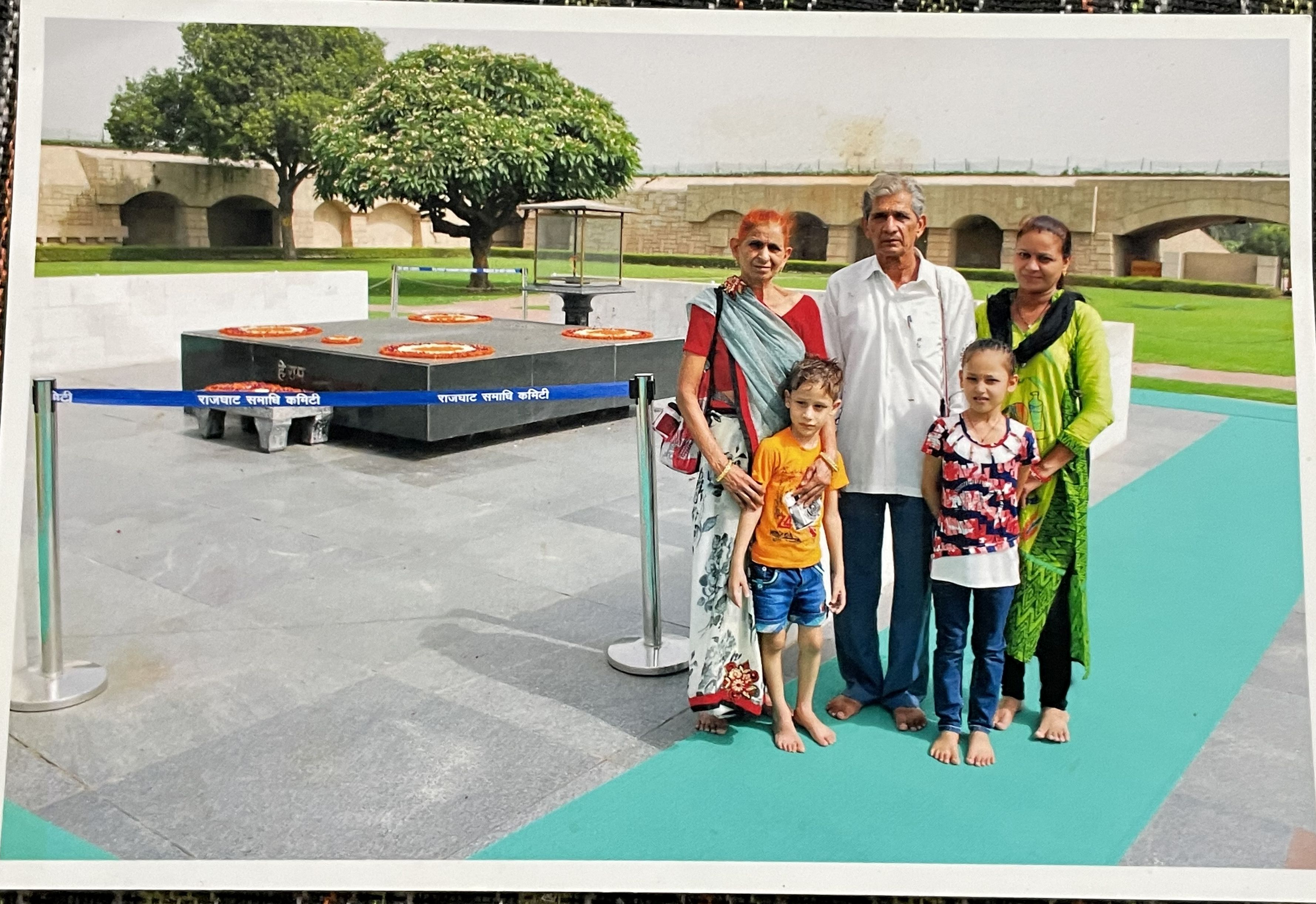

A tall, thin man with white hair and sunken cheeks, Jain travels from Damoh, Madhya Pradesh, to Delhi—a journey of more than 700 km to the north, 13 hours by train—a few times every year with a sling bag filled with letters, complaints, and appeals he has sent to judges, officials, ministers, prime ministers and presidents since 1997, and the orders that were passed.

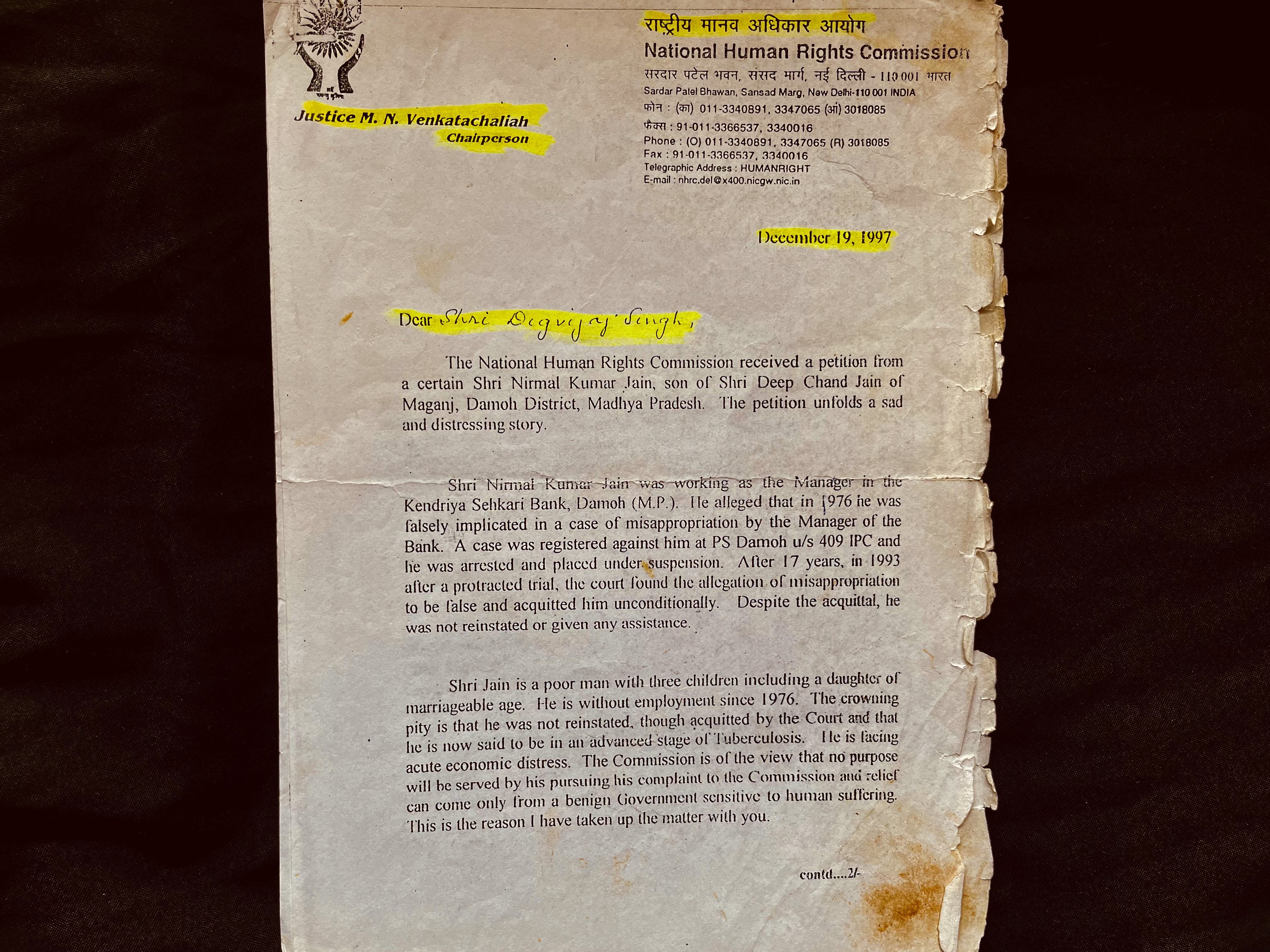

A letter from December 1997 was from Justice M N Venkatachaliah, a retired chief justice of India, who, as the chairman of the National Human Rights Commission (NHRC), had asked the Madhya Pradesh government to help Jain because “he has suffered for no fault of his own”. But the Madhya Pradesh government never did.

Jain was working in the district cooperative bank in Damoh in October 1977 when he was implicated in a false case of misappropriating Rs 4,816, which cost him his job, and drove him and his family into crushing poverty.

His acquittal in 1993, he realised, wasn’t enough to pick up the pieces and make some kind of life.

When he didn’t get his old job back, they remained poor, and two of his three children killed themselves in 1999 and 2000, Jain wanted the state to see that he was blameless yet ruined and respond to the tragic consequences he was suffering through no fault of his own.

Despite letters from Supreme Court justices who served as chairpersons of the NHRC, asking the Madhya Pradesh government to help Jain, and orders from the Home Ministry to the NHRC to investigate his complaint, as recently as last year, nothing changed for him.

Armed with years of desperate appeals and unaddressed administrative orders, which chronicle his decades of efforts to be heard, Jain is still shuttling between judges, ministers, and bureaucrats, filling his bag with more papers.

In a small and sparse room of a rest-house run by members of the Jain faith in Delhi, Jain organises his papers, gently placing the old and yellowing ones at the top of the pile and then making his way through the years. He goes to government offices and drops off letters with the grievances he has listed many times before; he tries meeting with journalists and asking them to write about him.

“A man is made a criminal, and his life is destroyed for raising his voice against corruption,” said Jain, his eyes welling up with tears. “I have been trying to get justice for 46 years. Is there any justice in this country or not?”

What The Papers Said

Jain believes the false case of misappropriating Rs 4,816.40 was imposed on him in 1977 because he called attention to corrupt officials at the cooperative bank in Damoh, where he got his first job as a samiti prabandhak (society manager) in 1972.

The newspapers covered Jain’s story for many years after his acquittal, when he didn’t get his old job back, his children passed, and he mounted his campaign for justice.

A newspaper report from June 2001, End of the road for him, said, “There seems to be no light at the end of the tunnel for Nirmal Kumar Jain. The 65-year-old (the paper got his age wrong) has lost two of his children to economic ruin, all caused by judicial and administrative apathy. Two months back, the desperate man tried to jump into the Lok Sabha—looking at the house of the people for justice.”

“In the last 25 years, Jain has run from pillar to post for justice–-but all in vain. According to Jain, he had approached the President, the prime minister, the home minister, the Madhya Pradesh chief minister, and a number of other members of parliament, including Moti Lal Vohra, Satish Pradhan and Jaibhan Singh Pawaiya, asking them for help. They all promised to—but never seemed to get around to doing it. Jain has also written a letter to US President George Bush.”

A report in the Telegraph in April 2009, Framed, son and daughter lost, still he will vote, said that Jain’s story “is the story of all the underdogs and their bleak struggle for at least a semblance of justice”.

“Four Supreme Court chief justices have written to the Madhya Pradesh government to look into Jain’s grievances. In all 27, letters have been sent from the office of former prime minister Atal Bihari Vajpayee and LK Advani. Nothing happened. But it hasn't stopped Jain from hoping–and voting.”

Now, Jain is on YouTube.

He has links to YouTube videos of his sit-ins at Jantar Mantar, interviews with reporters, or raising allegations of corruption against political leaders in Madhya Pradesh, even if they belong to the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP), the party in power and the one he is loyal to.

Donning the dark glasses his family insisted he wears while travelling to Delhi this month after cataract surgery in one eye, Jain could speak with a few channels.

“The prime minister’s office is in the south block. I must have given at least 100 letters to Modi ji,” he said in an interview with Jansansad News.

A Chief Justice Remembers

When we met Justice K G Balakrishnan, the chief justice of India from 2007 to 2010 and the chairperson of the NHRC from 2010 to 2015, he remembered Jain.

What Balakrishnan, the first Dalit to head the Supreme Court, remembered most about their first meeting on 4 July 2012 was that Jain’s wife, who had travelled with him to Delhi, looked unwell.

“I told him, ‘Please don’t trouble this woman. Let her stay at home. I felt so sorry because she could not walk,” he said.

What Jain remembered most, and almost comically about the first time he met the judge from Kerala, was the language barrier between them.

“Justice Balakrishnan did not speak one word of Hindi, and I did not speak one word of English,” he said, smiling. “But I told him everything.”

Over the years, Jain said that he had met with Balakrishnan at his home in Delhi, and while it hasn’t altered his circumstances, he said the judge was always kind.

“For no fault of his own, he lost his job,” said Balakrishnan. “Even though he was acquitted by a criminal court, the authorities did not reappoint him to his original post. Ever since then, he has been trying to get justice from the authorities and approaching various people.”

“He filed a complaint before the NHRC, and former chairpersons of the NHRC had given instructions to do the needful to help Mr Nirmal Jain. Nothing tangible happened,” he said.

While recalling some parts of Jain’s case and listening to us fill in other details, Balakrishnan said that it would have been easier to help him if he had moved the court, but he couldn’t afford a lawyer, which is why he went to the NHRC—“the poor man’s court”.

“There were a series of tragedies in his family, and he appeared mentally troubled. Even now, he is trying to get redressal for his grievances,” he said. “There cannot be reemployment as he has aged, but the authorities can consider some compassionate payment to him by the appropriate authorities. The state government has beneficial funds to help needy people.”

An RSS Man

Largely forgotten by people in the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh (RSS) in Delhi and Damoh, Jain said that he was a lifelong member of the Hindu nationalist organisation, going to its shakhas since the age of nine.

As an RSS man, he had always believed it was his duty to speak out against corruption, making him enemies across party lines.

At the cooperative bank where he worked in the 1970s, Jain said that he stood up to the bank manager and refused to extend a loan to someone already in debt. Before that, he spoke up when the money spent on purchasing stationery was more than the stock acquired and false bills were made to cover the difference.

“If I were told to extend a loan to someone in debt, I would not do that. There were other wrong things that I did not do,” said Jain. “When I saw something was wrong, I spoke up. That is why I was slapped with a case.”

A case under section 409 Indian Penal Code, 1860—criminal breach of trust by a public servant, or by banker, merchant or agent—was registered by the police, then under the Congress Party.

Jain believes he was treated poorly when Congress was in power because he was from the RSS. But nothing changed when the BJP came to power in Madhya Pradesh in 2003.

The RSS, the ideological parent of the Hindu nationalist party, was in power at the centre when Jain beseeched Vajpayee in Parliament in 2001, and it came back to power in 2014 with Narendra Modi as prime minister.

Naming the ministers and elected BJP leaders he had approached over the years, Jain said, “For the ideology that I sacrificed my life and my family, spoke out against corruption, even that did not help me.”

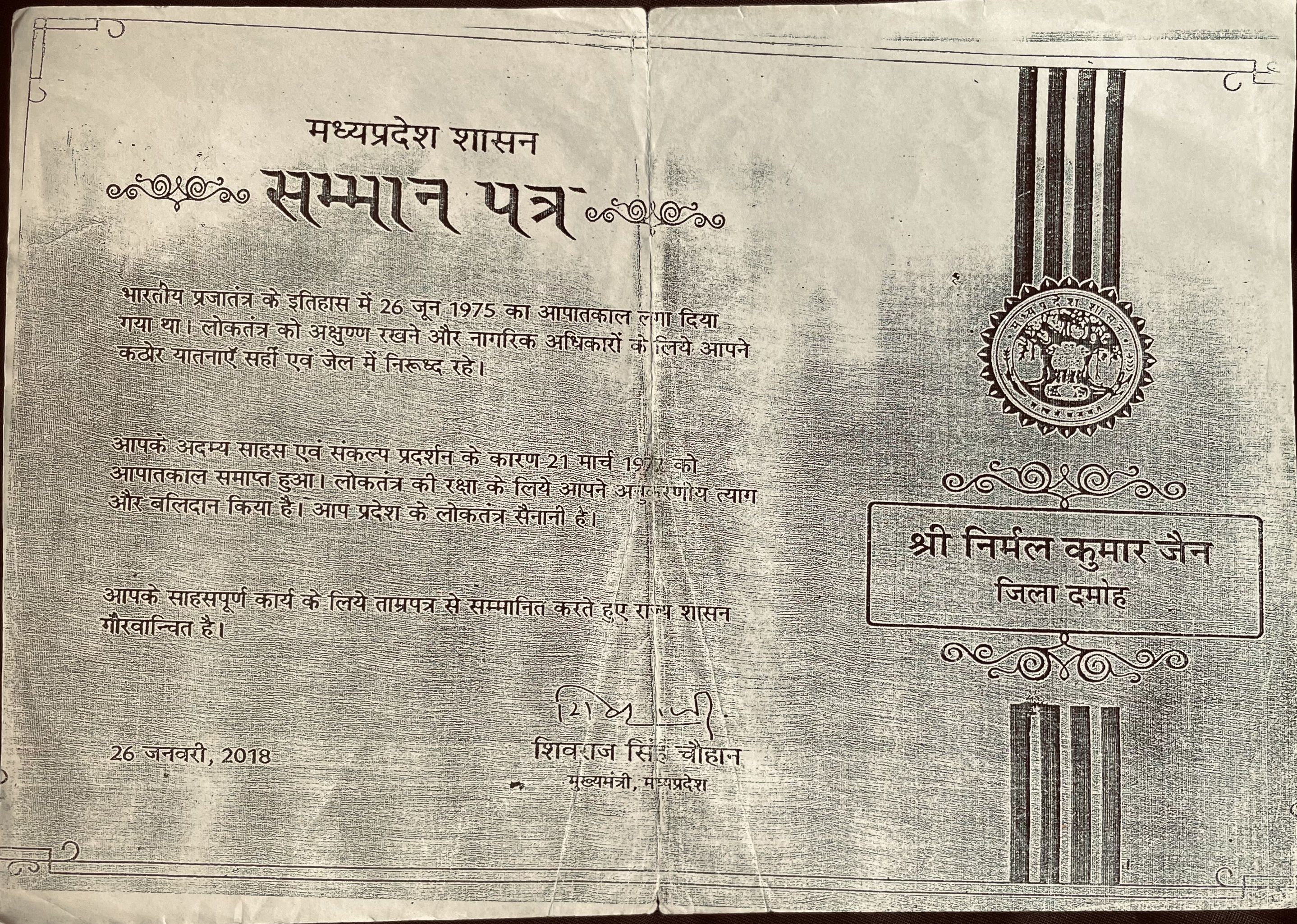

In his stack of papers, Jain has a certificate from chief minister Shivraj Chauhan, recognising that he was among those jailed for opposing the Emergency imposed on 26 June 1975 by Indira Gandhi, then prime minister and leader of the Congress Party.

“You have made an exemplary sacrifice to protect democracy. You are a soldier of democracy for the state,” the certificate said.

Two years ago, Jain said he applied for and started receiving the monthly pension of Rs 25,000 given to those who were jailed during the Emergency.

When Prime Minister Modi remembered those who fought the Emergency, Jain said that his wife wrote a letter to Modi, appealing for justice for her husband instead.

“The wife of a man who spent 18 months in Emergency wrote to Modi saying that ‘he does not want your salaam, he wants insaaf,’” he said. “My whole family is loyal to the BJP. That is what hurts the most.”

After all these years, his wife, Kanta Jain, said she was worried about her ageing husband’s health, but they had been fighting too long to stop.

“We have seen such grave injustice, lost our children, home, and livelhood, that we cannot stop,” she said. “We have lost too much. We can only stop fighting when we stop breathing.

Branded A Thief

Jain was out on bail, but no one was willing to work or do any business with him after the case.

To feed his family, Jain, like his father before him, started crushing wheat and selling flour in the local mandi. He would also buy rice and vegetables from nearby villages and sell them in the market.

“My biggest fear was for my daughters. Who would marry the daughters of a ‘thief’? That is what they called me,” he said. “This fear drove me mad with worry. Even if your name is cleared later, people don’t remember that. They only remember you were accused of being a thief.”

Despite his poverty, Jain said he kept raising his voice.

Recalling the day when he travelled to Chhatarpur district and distributed pamphlets inside the court, accusing a magistrate who had transferred there from Damoh of taking a bribe from the bank manager, Jain said the police picked him up, beat him and sent him to Bijawar jail, where dacoits from Bundelkhand were held.

Jain said he complained, and an investigation into the case was ordered by the MP government, but it was never concluded.

Jain said he sold his family home to pay for the six months he spent in the hospital. His family lived in a rest house for pilgrims. Now, he lives with his wife, Kanta, surviving daughter, Savita Jain, and two granddaughters in a place he rents for Rs 5,000 monthly.

When he recovered and petitioned the Jabalpur High Court, Jain said the bank manager’s lawyers beat him with sticks and broke his foot.

Jain said he was acquitted on 25 January 1993 by a first-class magistrate of the Damoh civil court, and a case was registered against the bank manager who had implicated him and decided against him. But when he went to get his old job back at the cooperative bank in Damoh, the bank president refused him.

“It was Congress rule. Then, someone said, ‘Write to the human rights commission. Justice Venkatachaliah is a good man,’” he said.

Letters From Justices

In his sling bag of papers, a letter dated 9 December 1997 from Justice M N Venkatachaliah, who was then the chairperson of the NHRC, to Digvijay Singh, a Congress Party leader and chief minister of Madhya Pradesh at the time, saying that Jain had “a sad and distressing story”.

Venkatachaliah, a former chief justice of the Supreme Court, said that Jain was a poor man with three children, including a daughter of marriageable age, who was not reinstated in his old job even after the case against him was dismissed after 17 years.

“The Commission is of the view that no purpose will be served by his complaint to the commission, and relief can only come through a benign government sensitive to human suffering," Venkatachaliah wrote, requesting the CM to “personally look into the matter” and give “adequate assistance under any prevailing government scheme or from your Chief Minister’s benevolent fund, which could be of a magnitude that would make him survive without the grudging humiliation of poverty bordering on destitution”.

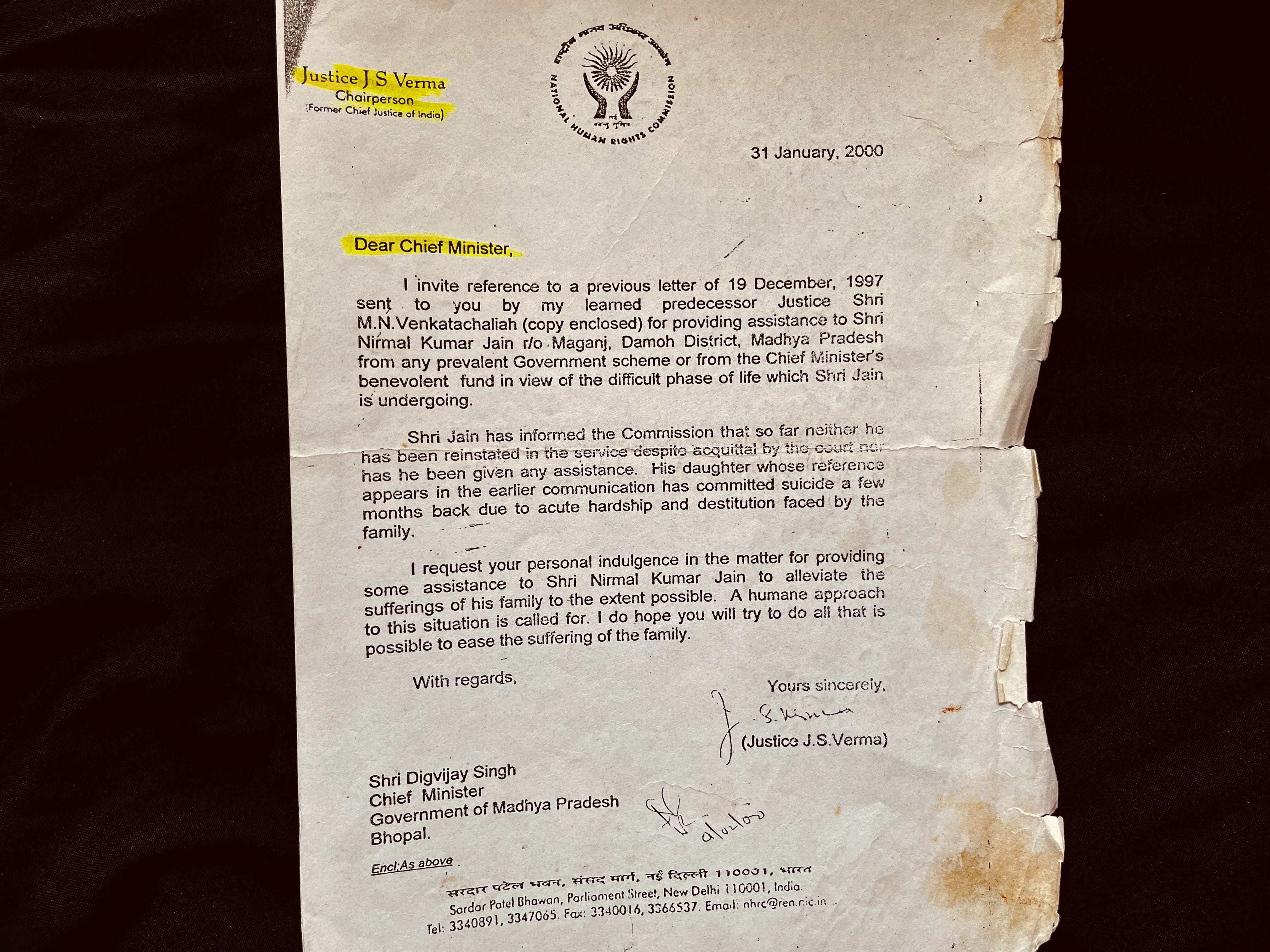

In a letter three years later, on 31 January 2000, Justice J S Verma, a retired Supreme Court chief justice and chairperson of the NHRC after Venkatachaliah, wrote that no action had been taken in response to his predecessor’s request for intervention—Singh was neither reinstated nor given any assistance.

By this time, Jain’s 23-year-old daughter had set herself on fire and died.

Verma’s letter to the chief minister said, “His daughter, whose reference appears in an earlier communication, committed suicide a few months back due to acute hardship and destitution faced by the family.”

Requesting the CM’s “personal indulgence” to alleviate the suffering of Jain and his family, Verma wrote, “A humane approach to this is called for. I do hope you will try and do all possible to ease the suffering of the family.”

A reply from Singh three months later, on 23 March 2000, said he had asked Mr Jain to meet him to see what help could be provided.

Jain said he asked Singh to give his son a job, and he agreed. He left his son’s certificates with the chief minister’s officials and followed up, but he never got the job.

Forged Documents

Jain maintains that the MP government told the NHRC that a “decree” passed against him by the assistant registrar of cooperative societies (ARCS) in 1977 was still pending against him, and he owed the state Rs 19,382.

Jain said when he had tried jumping into the well of the Lok Sabha in April 2001, it was to demand the MP government show the original documents of the decree it claimed was pending against him.

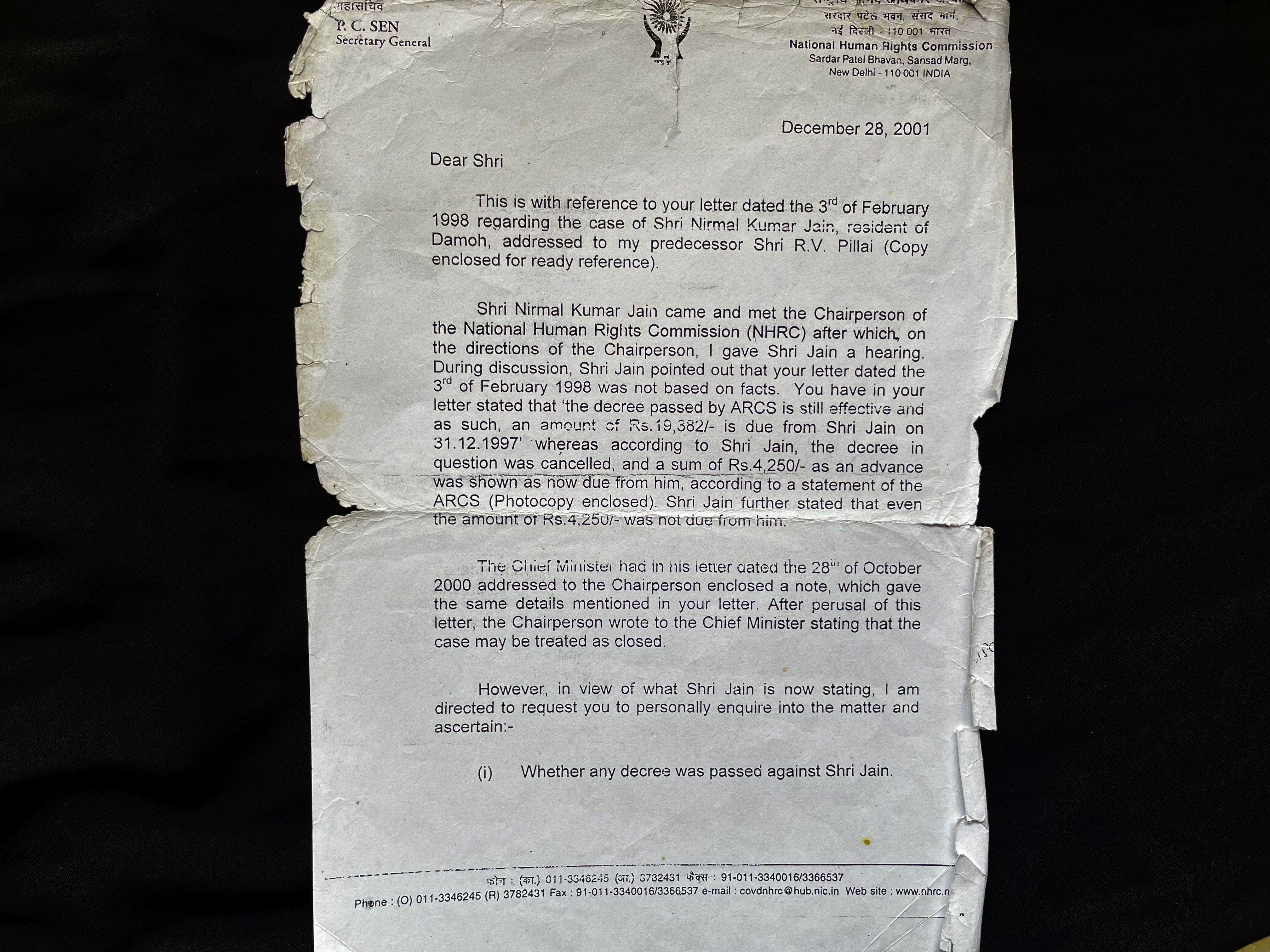

A letter dated 28 December 2001 from the NHRC to the MP government said that Jain had alleged the documents sent by the MP government about the decree were false.

The letter asked the government to “peruse the original documents” and ascertain whether any decree had been passed against Jain and whether it had been cancelled.

In April 2002, the Hindustan Times and The Pioneer newspapers ran stories about him—Cleared By Court, Staffer Still Awaits Justice, and For NHRC, Issues Are Important.

On 23 July 2002, Kailash Chandra Joshi, a Rajya Sabha member and an eight-time MLA from the Bagli constituency in Madhya Pradesh, raised a question in the upper house; why was the MP government not providing the information sought by the NHRC?

Even after so many years, Jain is still determined to prove the MP government lied about the decree. He was, after all, acquitted by the court.

Writing to the Home Ministry on 1 January 2018, Jain said, “The MP government gave fake documents about me to two chairpersons of the NHRC—Justice Venkatachaliah and Justice Verma.”

“If the MP government had followed Justice Venkatachaliah’s letter, I would have got my job and money,” said Jain. “I would have been able to support my daughter. She would not have killed herself.”

Death Of His Children

Jain said his daughter, Babita, killed herself on 10 July 1999 following an abusive marriage with a man who would drink and beat her. But because he was in such dire straits himself, she never said anything to him.

“My heart was broken when I found out,” said Jain. “My heart broke that she thought she should be a burden on me because I would not be able to help her.”

Jain’s son, Rajesh, was 25 when he killed himself on 31 August 2000.

Jain remembers it was Janmashtami, the day Hindus believe the day that their god Krishna was born.

Jain said his children died because he was poor, deeply distressed and unable to help him. His wife never recovered from the shock. The circumstances of his mother’s death—she died alone in a shelter home—still haunt him.

The newspaper report from June 2001 said that after his children died, Jain wrote to the president of India: “I do not want justice now. My only request is that, as a constitutional head of the country, you make a provision so that no one has to die each day for 25 years like me and see his children die one by one. My wife and children have suffered immense pain and trauma. My son was able to educate himself by cutting beetle nuts and selling them. What shall I do with his degree now?’”

Getting His Job Back

In 2000, Vajpayee appointed Bhai Mahavir, a BJP leader and a famous RSS pracharak, who Jain said had read about him in the newspapers, met him and told Justice Gulab Chand Gupta, a judge in the Jabalpur High Court at the time, to look into his case.

On 25 March 2002, nine years after he was acquitted in the misappropriation case, Jain returned to the bank as a samiti prabandhak, but his salary was Rs 3,000 a month while others in comparable posts were getting Rs 12,000.

A newspaper report of India Today in Hindi published on 2 July 2003 said that Jain was given “only” Rs 1,46,105 as compensation for 24 lost years.

The news report cited an anonymous police official who said that Jain was being harassed, but he didn’t know why.

Jain said he should have got Rs 10 lakh as compensation. He spent the money he received on getting his younger daughter, Savita, married.

“All I said was that give me the same amount as the person who joined me is making,” said Jain. “Is that something wrong?”

Two years later, when he was 58 years old, Jain said he was given compulsory retirement in June 2004.

A Letter That Never Was

More than 10 years after Venkatachaliah wrote to Digvijay Singh, Jain met with another NHRC chairman—Balakrishnan.

In his appeal to Balakrishnan, Jain wrote: “After the stain of a thief on my forehead, no one would believe me or give me a loan. My children would eat supari all day. Sometimes, I would see them bleed when they would bite their finger. My wife sewed all day. The whole neighbourhood would say that she has raised them on blood, not milk.”

“What is my fault that my life was destroyed?”

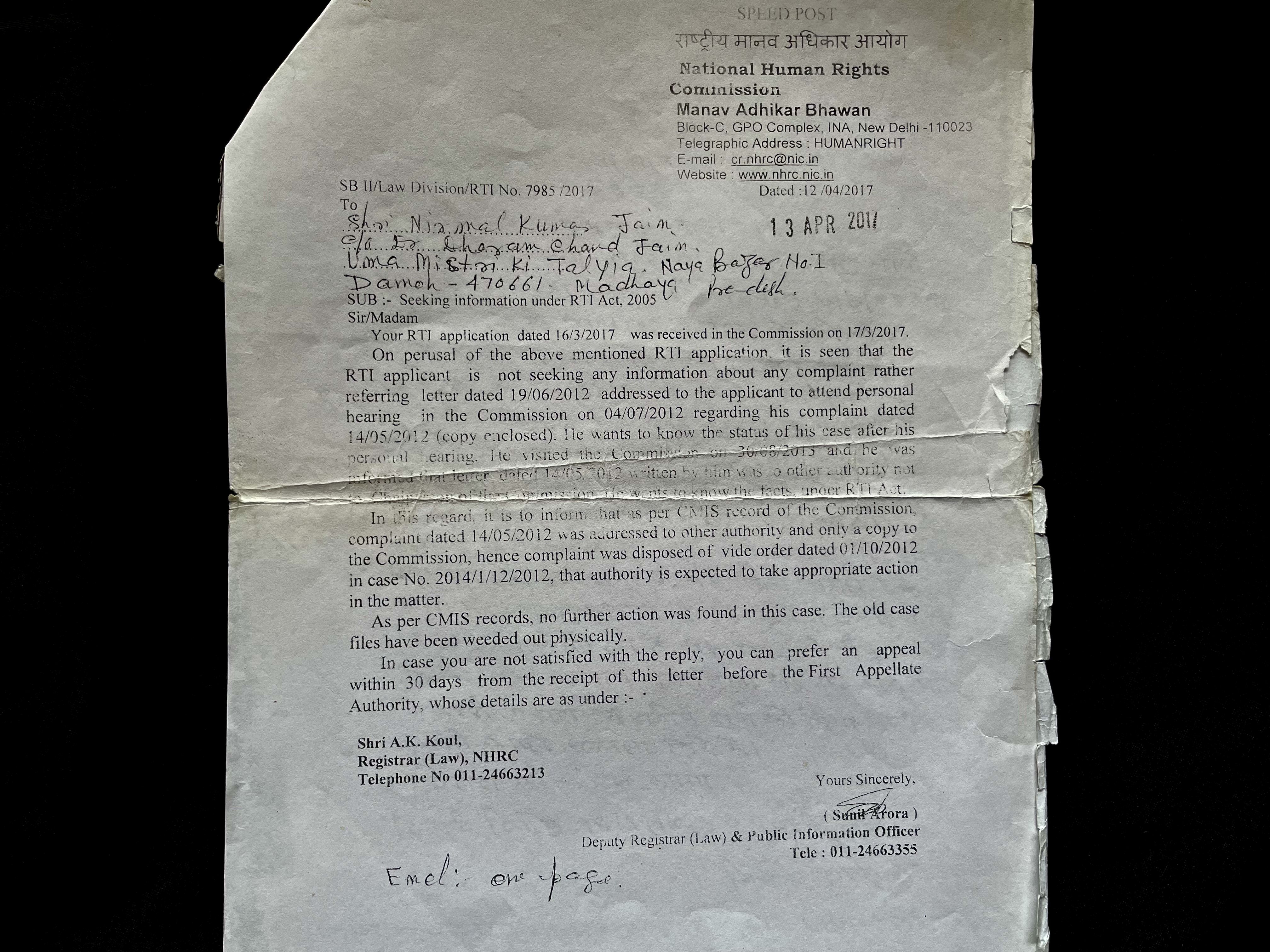

Jain said that when he did not hear anything after meeting Balakrishnan on 4 July 2012, he sent letters to the NHRC and filed an RTI application on 16 March 2017.

In a response dated 13 April 2017, the NHRC told him that his request was not seeking information but inquiring about the status of his case after his “personal meeting” with the chairperson. The letter said his letter dated 14.05.2012 was to the “other authority”, and the NHRC disposed of the case.

In 2017, the chairperson of the NHRC was the former chief justice of India, Justice H L Dattu.

“My head spun after reading the NHRC letter,” he said. “How was a constitutional body saying this? Why did the chief justice meet me if there was no letter.”

When we asked Balakrishnan about the letter sent by the NHRC, the former chairperson said these kinds of technicalities were “irrelevant”.

“Such poor people are coming from the States,” he said. “The question is whether we can help them or not. If we can, then we should help them.”

The Hindu published an article, Whistleblower unhappy with NHRC’s order to close his case, about Jain starting an indefinite fast.

The Times of India published an article, A septuagenarian's four decades of battle for rights and honour, which said, “Jain had met former NHRC chairman KG Balakrishnan but to no avail. Assurances and recommendation letters by competent authorities to chief minister Shivraj Singh Chauhan did not bear any fruit for 70-year-old Jain, who had even tried to jump from the visitor’s gallery of Lok Sabha to draw the attention of the lawmakers in 2002. Parliamentarians also raised his issue in the House.”

“I am completely saddened by the way the NHRC dealt with my case,” Jain told the newspaper at the time.

In an affidavit he submitted to the Supreme Court on 16 August 2017, where he accused the NHRC officials of committing fraud against him and Justice Balakrishnan, Jain wrote, “Inside the courtrooms, we are asked to take an oath of truthfulness by placing our hands on Gita. I take an oath by placing my hands on the heads of my children and my mother, which are higher and greater than Gita, Bible or Quran, that my letter dated 14.05.2012 was in the name of Hon’ble Justice Balakrishnan…”

The Year Of Unrequited Letters

Ten years would pass before Jain met Balakrishnan again. He was no longer the chairperson of the NHRC, but after their meeting on 29 September 2022, he wrote to the NHRC, asking it “to do the needful” in Jain’s case.

“It is related to an incident that happened long ago,” Balakrishnan wrote.

On 25 May 2022, Jain wrote to the NHRC, “I just seek an opportunity to present my case to the commission so that I can prove that due to the fake documents presented by the MP government and their inhuman work culture has disturbed the mental balance of my family and caused loss of three lives including my mother, daughter (burnt herself), son (committed suicide) and my wife is mentally unstable. I request accordingly.”

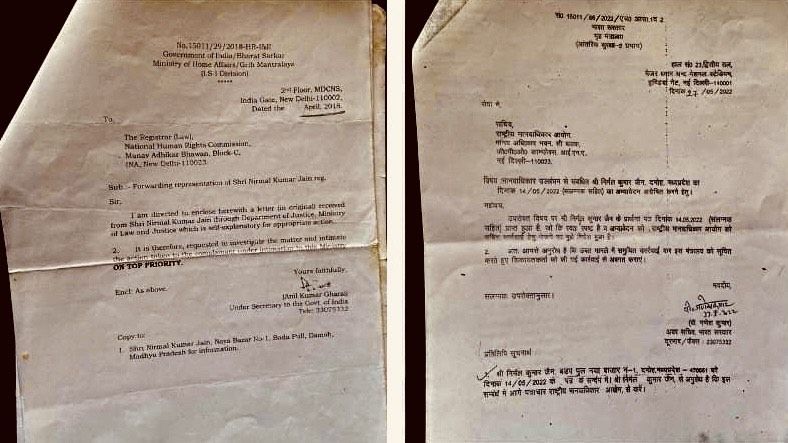

The home ministry, in response to Jain’s complaint of 14 May 2022, on 27 May, wrote to the NHRC to carry out a proper investigation and inform the ministry and the complainant.

The Central Vigilance Commission, on 5 December 2022, in response to Jain’s complaint of 5 October 2022, wrote to the NHRC.

The chairperson of the NHRC since June 2021 is Arun Kumar Mishra, a retired judge of the Supreme Court.

The Home Ministry also wrote to the NHRC on 23 June 2017, 22 August 2017, 18 December 2017, 02 February 2018, 13 February 2018, 16 February 2018, and 6 April 2018.

On 16 February 2023, the day before Article 14 met him, Jain shared an open letter to the “journalists brothers”, saying that he was a 75-year-old man resting his head on their feet to get him justice.

He enclosed the official correspondence from 2022.

More Of The Same

The person who answered the phone at the NHRC said that he could not provide information about Jain with just a name, but then looked up his name on the computer and said there were 125 entries against his name. He couldn’t tell if they were all related to Nirmal Kumar Jain from Damoh.

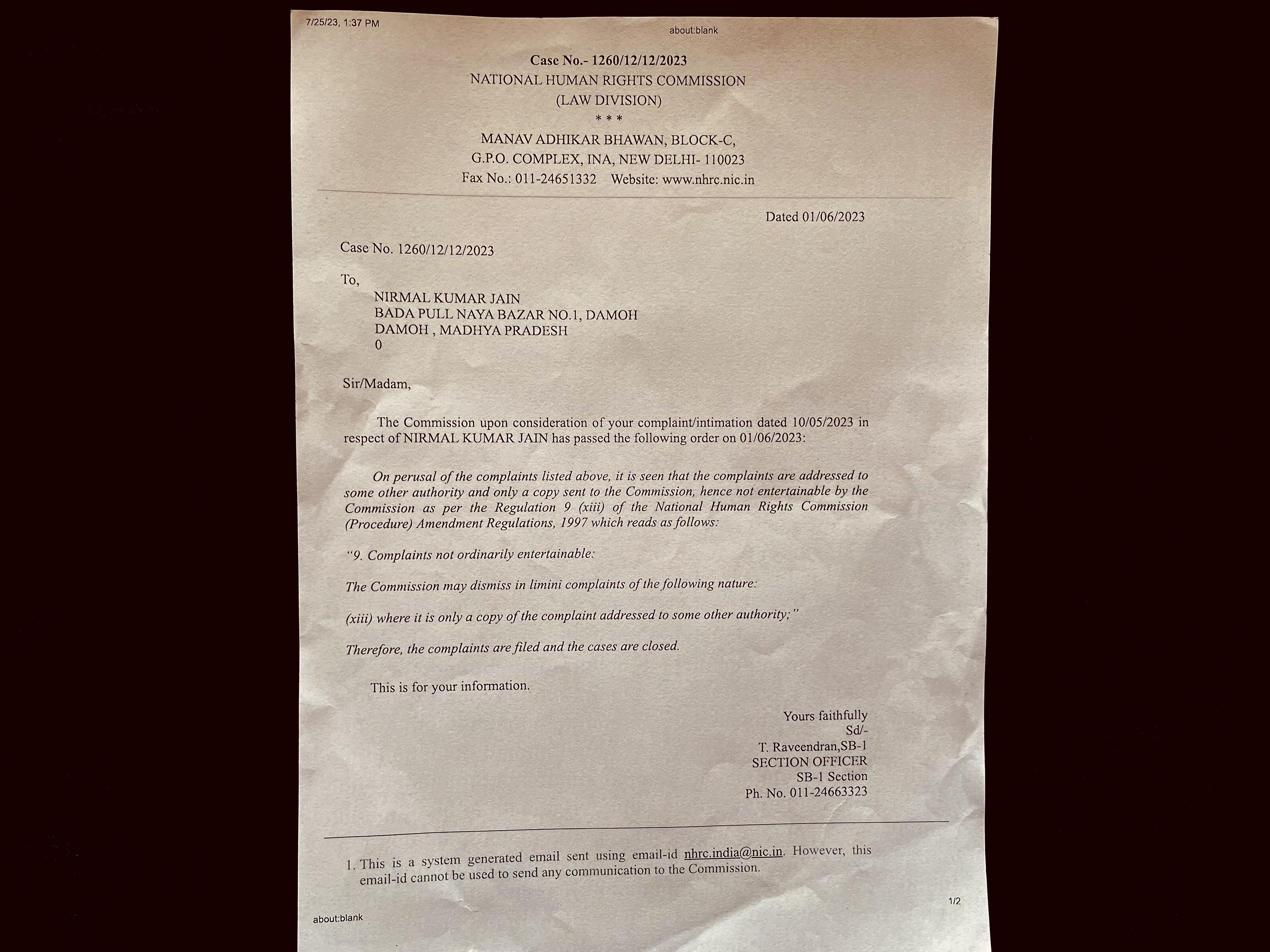

A visit to the swank, air-conditioned offices of NHRC in Delhi yielded nothing more except printouts of the two latest orders dated 6 September 2021 and 1 June 2023 with the bureaucratic language similar to the letter of 13 April 2017 where they told him his matter was disposed off because his letter was addressed to the “other authority”.

“On perusal of the complaints are addressed to some other authority and only a copy sent to the Commission, hence not entertainable by the Commission…”

While exclaiming at the number of entries and how far back they went, the person at the desk said he could not provide any further information.

“This man’s case seems to go a long way back,” he said. “All the applications are closed.”

A Forgotten Man

The main RSS offices in Delhi were the same. No one had heard of Jain or his decades-long story intermittently reported for many years.

After listening intently to the story, an accountant in one of the offices shrugged and remarked that “so many people spend decades seeking justice in India”.

Except for a letter that the RSS district president at the time, Pramod Sahu, sent to the editor of the Panchajanya, a Delhi-based weekly newspaper of the RSS, on 19 August 2000, there was little evidence of the organisation’s involvement in Jain’s battle.

That letter was prompted after Jain’s daughter told the newspaper that her sister had killed herself, and her family had suffered because her father was in the RSS. The headline was, “Papa, your only fault is that you are a member of the RSS.”

Sahu wrote that Jain was a swayamsevak of the Damoh shakha, and the Madhya Pradesh government (under the Congress Party) had done him and his family a grave injustice. But the Panchajanya reporter, he wrote, had twisted the story to malign the RSS, and the Punjab Kesari newspaper had picked it up.

In what seemed like a political expedition, Jain was dispatched with the letter to meet the editor in Delhi, where he protested against the “Congress-minded reporter” who had written the story “maligning” the RSS.

When we asked him about the RSS’ absence from his fight, Jain said it had been such a long time that people who knew about it were old or had passed away, and members now would not know his name. He said it was enough that Bhai Mahavir, the RSS pracharak Vajpayee made governor of MP in 2000, had helped him get his job at the bank.

“That was a crucial thing he did. He met me three times,” said Jain. “But this is my fight against the government and officials, and they must respond.”

Jain said that he wanted an investigation into the assistant registrar of the cooperative society, who he said passed the “false” decree of corruption at the behest of the bank manager of the cooperative bank in Damoh in 1977, the MP government, for allegedly sharing forged documents about him with the NHRC in 2001, and the NHRC for dismissing the meeting and letter he sent to Justice Balakrishnan in 2012, five years later in 2017.

“I know it has been very long, and people have become old, died, or moved on. But I want an investigation,” he said. “This is for justice. I want the truth to come out. I want to prove what they did to me was wrong.”

A Difficult Man

When we first phoned him, Ram Krishna Patel, the RSS representative in Damoh, said he recalled hearing or reading about Jain before Covid-19 but could not say anything about it.

“It is an ancient story,” he said.

Two weeks later, Patel called back and said he spoke with the RSS people from “30 or 40 years ago” and pieced together Jain’s story.

While he conceded that Jain had “suffered too much and for too long”, Patel said that his relentless pursuit against corruption had alienated everyone in Damoh who could have helped him.

“He has accused all the powerful people in Damoh of corruption. Everyone was afraid,” said Patel. “Even the people who could have given his job back, he opposed them.”

According to Patel, after a while, people saw him as a crank who was always critical of everyone and everything. But he understood why Jain did it.

“When people lose everything, they feel they should oppose everyone,” he said. “But if you want a job, you can’t put cases against people who will give you the job?”

Jain said that he couldn’t help himself.

Even his loyalty to the RSS and BJP has not stopped him from raising allegations of corruption against local BJP leaders and MLAs, which he knows hasn’t helped his cause.

“It is in my blood to say something when I see something wrong. I have to fight,” he said. “There is perhaps some injury inside me. I can't stop fighting.”

An Ageing Man

While her father spoke only of justice, 35-year-old Savita Jain said any monetary relief that came their way would be a big relief to her parents, who, after her brother died, felt very afraid about growing old, poor and alone.

“It would have been okay if they had their son,” she said. “I’m also very troubled. I have two kids. I don’t know whether to see them or look after ageing parents.”

Despite growing concerns about his age-related health issues, Savita said she was powerless to stop her father’s visits to Delhi. A small victory was when she persuaded him not to go immediately after his cataract operation.

“He doesn’t listen, and we understand that he won’t stop,” she said. “If someone has fought for 46 years, that person should get success. Isn’t justice supposed to win, even if it takes a long time?”

When we asked him if he still believed in India’s institution after all this time, Jain said he believed in God.

“I believe in God,” he said. “God is always on the side of the truth, and I’m telling the truth.”

(Betwa Sharma is managing editor of Article 14.)

Get exclusive access to new databases, expert analyses, weekly newsletters, book excerpts and new ideas on democracy, law and society in India. Subscribe to Article 14.