Delhi: Hamida Begum, 74, has lived in Batla House in southeast Delhi, a predominantly Muslim area near Jamia Millia Islamia University, for more than six decades.

She shares her home on Muradi Road in khasra 279—a unique identification number assigned to a plot of land—with her daughter Saima Begum and her husband, and their children, in the house she claimed her late husband built in the 1960s.

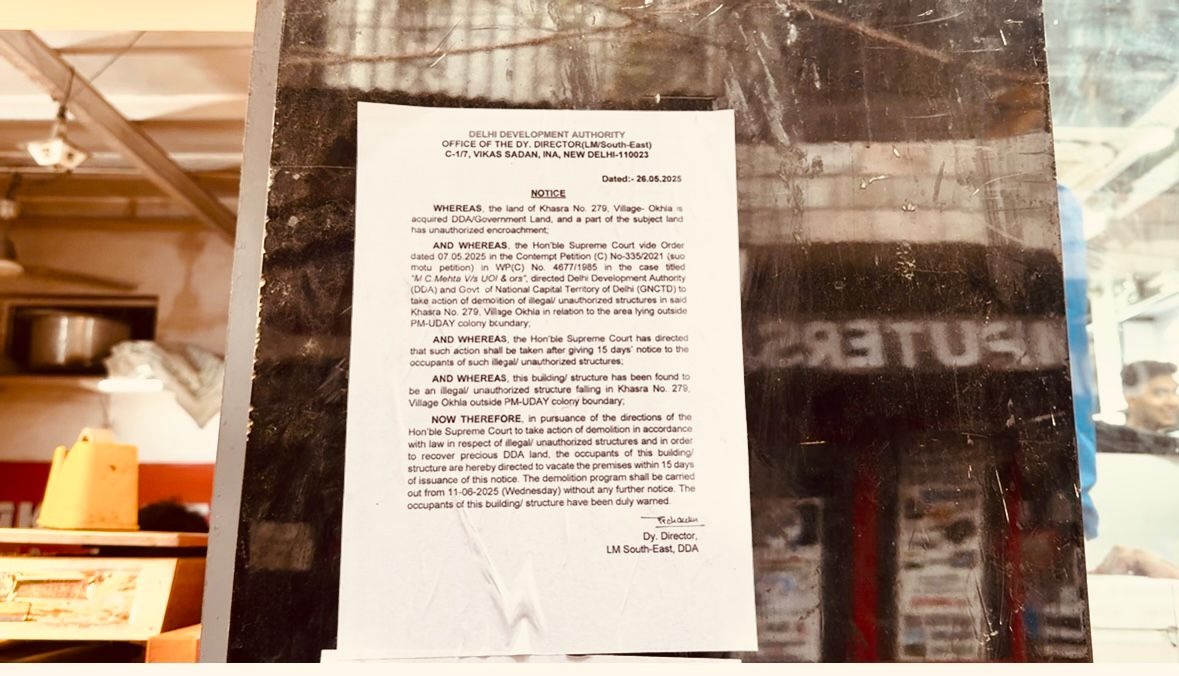

On 22 and 26 May , the Delhi Development Authority (DDA) and the irrigation and water resources department of Uttar Pradesh (IDUP) issued demolition notices for plots in khasras 277 and 279. The IDUP claims certain plots lie within the historical Yamuna floodplain and are legally theirs.

According to media reports, at least 52 homes in khasra 279 and over 100 in khasra 277 were marked with a red cross or had notices pasted on residents’ doors.The notices followed a 7 May Supreme Court order directing the removal of encroachments in the two khasras.

Begum’s house was among those marked for demolition. “I couldn’t understand, in one moment they ended everything,” she said.

“I have been living in this house for more than 60 years,” she said. “This house was built by my husband, Qamal Islam. I became a wife here, a daughter-in-law, then a mother, and now a mother-in-law. Every wall has memories. This house is my entire world.”

Begum’s despair is echoed across Batla House, where families who have lived for decades now find their homes suddenly branded as “encroachments”.

This is just the latest in a pattern of State actions against Muslim properties, particularly in BJP governed states nationwide.

Article 14 previously reported, in April 2022, governments in New Delhi, Gujrat, Uttar Pradesh and Madhya Pradesh had demolished properties belonging almost entirely to Muslims after communal riots incited by Hindu extremists, often justifying the demolitions as ongoing action against encroachments.

In October 2023, Article 14 reported on how the Mathura police and district administration demolished 135 Muslim-owned houses deemed to be encroachments, while Hindu homes in the same area remained.

A year later, in October 2024, Article 14 reported on how the BJP government in Assam demolished Muslim houses while leaving Hindu homes intact, ignoring a Supreme Court hold on demolitions.

Stress & Anxiety

In May, demolition notices instructing residents to vacate their properties within 15 days were served to over 150 homes in Batla House, triggering panic among residents.

Though the Delhi High Court later stayed the demolitions, the relief is temporary. With court hearings repeatedly adjourned and no final resolution in sight, families continue to live under the looming threat of eviction.

Among those affected were four residents, including Hamida Begum, whom we interviewed, who said they have lived in Batla House for over five decades, but the fight for their homes was endless.

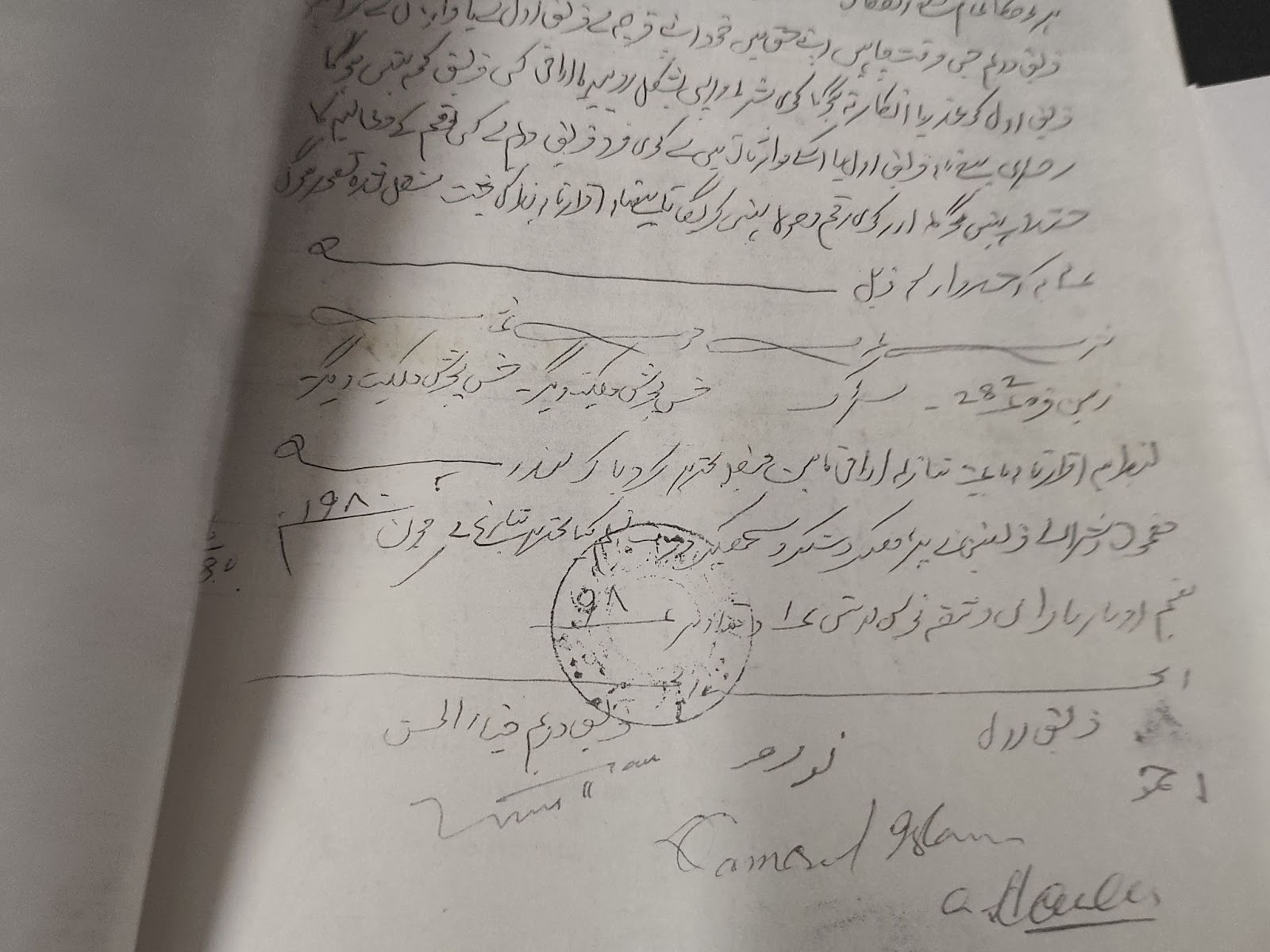

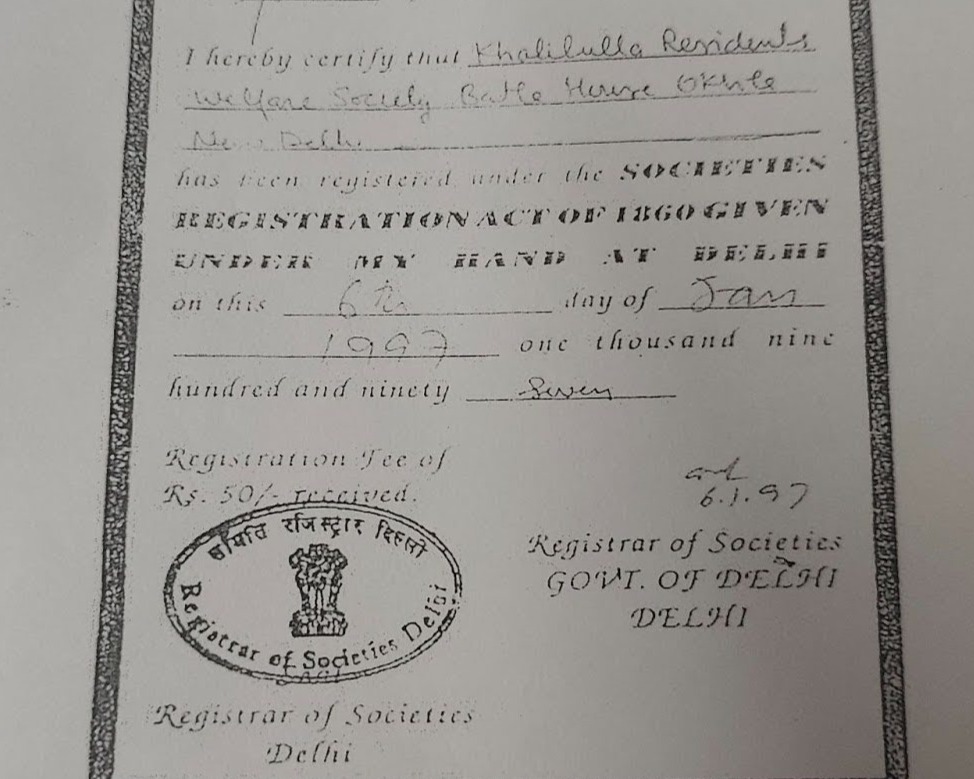

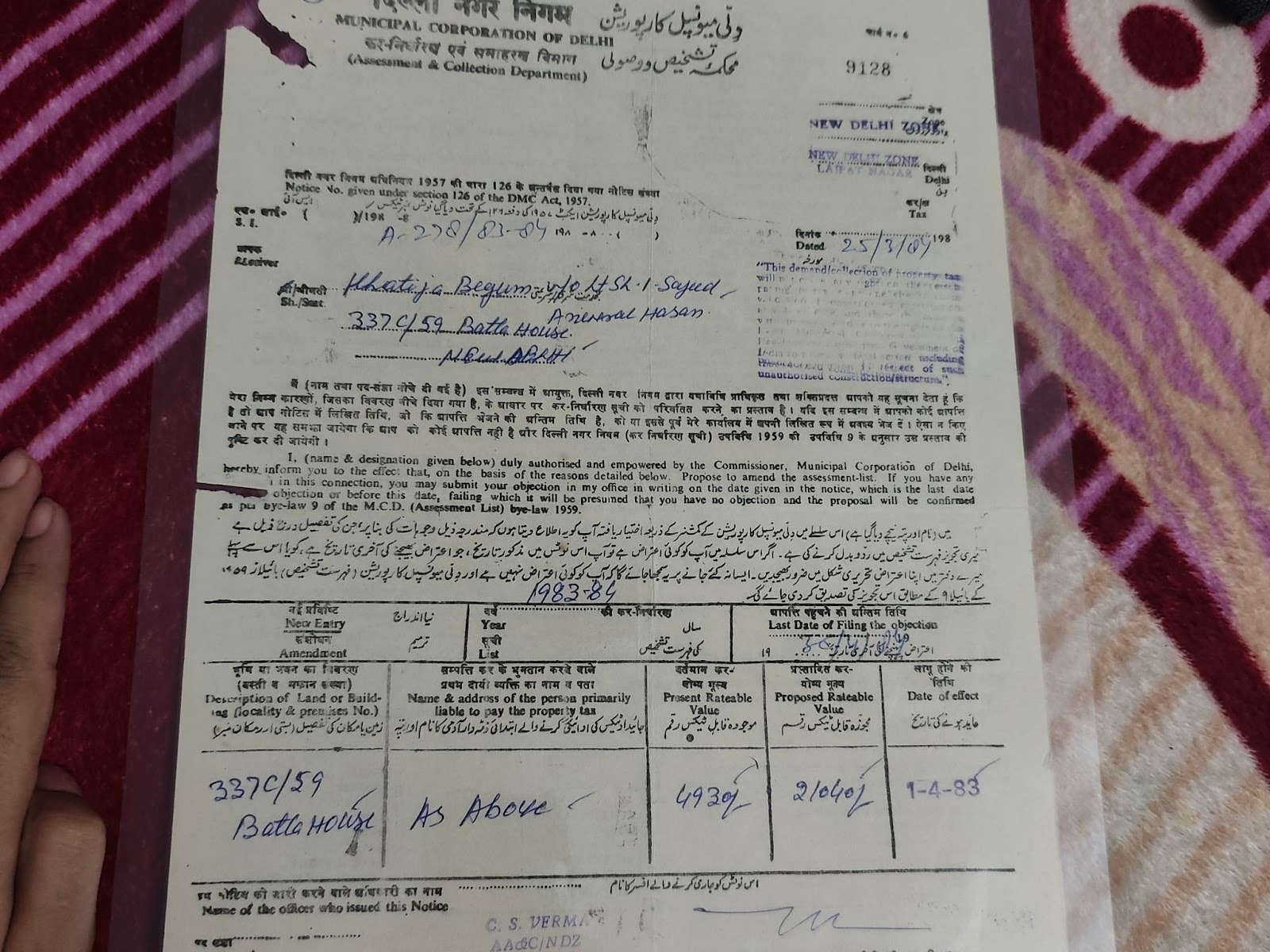

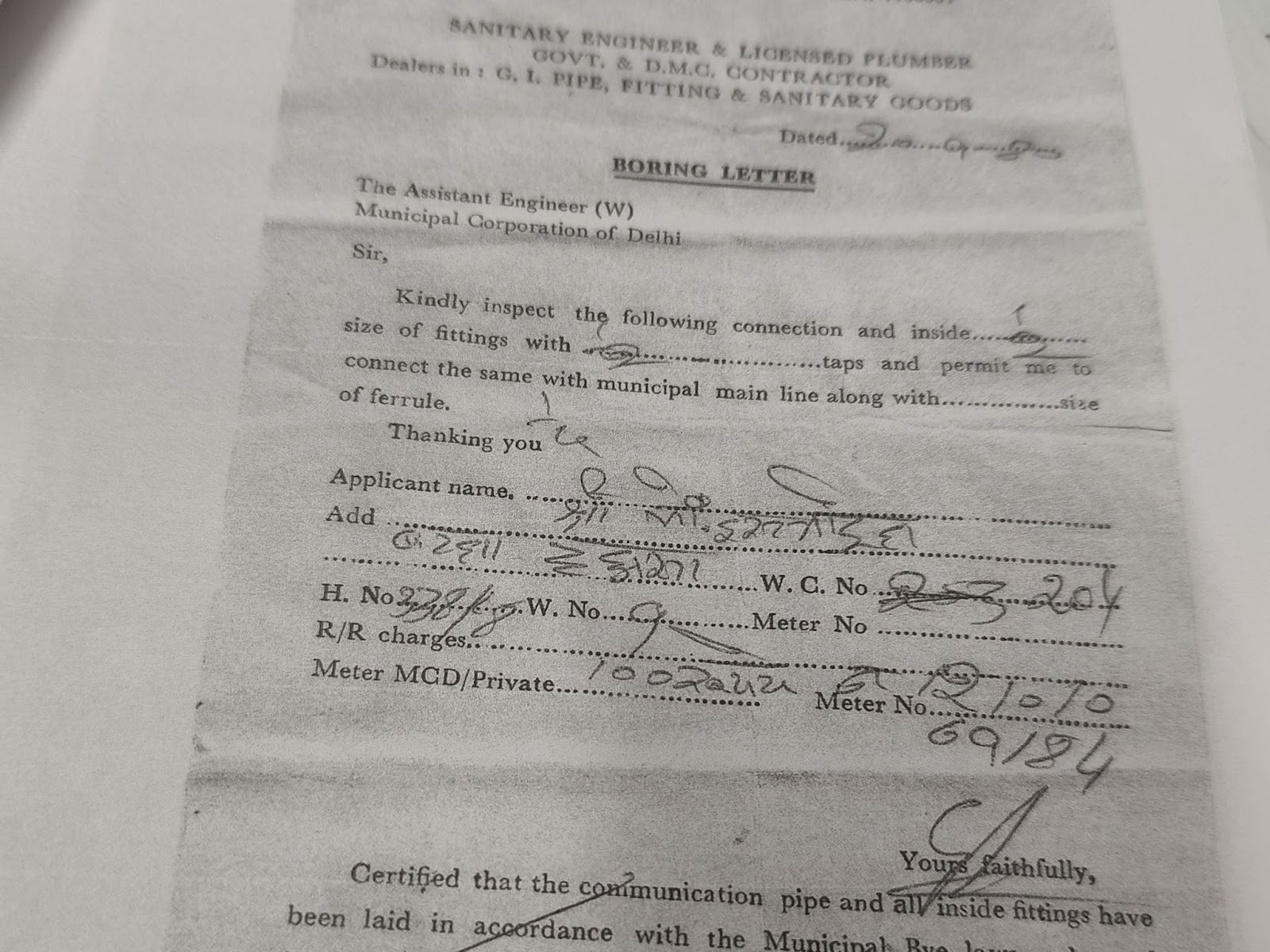

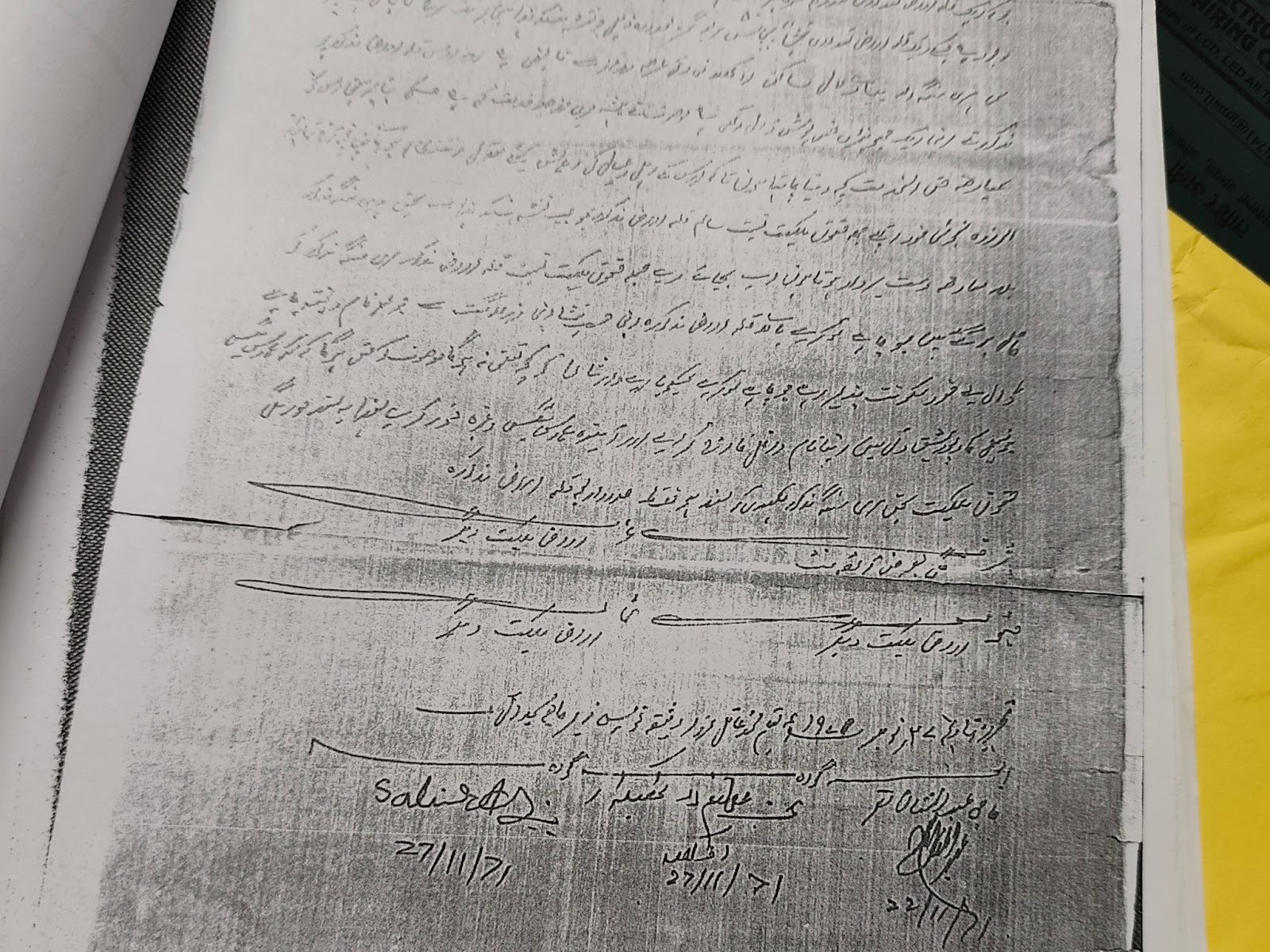

Article 14 reviewed documents of the four residents, including sale deeds, property surveys, tax records, and municipal water records, from 1971, 1980, 1983, and 1984. However, the residents said the structures were even older, and that they procured official documentation only years later.

56-year-old Activist Tahir Ali, who owns a shop in Batla House, has now become a full-time voice for those threatened with demolition. He said he was contacted daily by anxious neighbours seeking reassurance that they still had a chance for justice.

Stress and anxiety, he added, had taken a devastating toll: two people died from shock after receiving the demolition notices, and many others were bedridden.

According to Ali, none of the residents had papers dated before the 1980s, because older records had been written in Urdu, which most lawyers and officials could not interpret. Families had therefore converted their records into Hindi or English decades after the houses were first built.

For Ali, the struggle is about principle as much as survival. “If we let this happen here, tomorrow it will happen anywhere,” he said. “We are citizens, taxpayers and human beings. We are not encroachers.”

Temporary Relief

After their homes were marked for demolition, Batla House residents rushed to court to secure temporary stays.

In June, the Delhi High Court ordered status quo on demolitions till 10 July in response to petitions filed by several residents.

The court later granted interim protection to at least six properties, noting that the demolition notices were vague and did not specify which exact structures were targeted. In another case, seven families secured temporary relief when the court observed that some houses marked fell outside the boundaries of Khasra 279.

Yet, the relief residents secured was not permanent.

Since May, they say, they have been dragged from lower courts to the Delhi High Court, and even the Supreme Court, yet no substantive arguments have been heard.

In July, the High Court could not hear the Muradi Road (Khasra 279) matter for lack of time and fixed the next date for 6 November.

In the Supreme Court level too, the process has stalled. In early June, the court declined to halt the demolition drive outright, instead giving only tentative dates for hearing after the summer vacation.

Residents say this has created a situation where neither the High Court nor the lower courts will hear arguments, deferring instead to the Supreme Court, which itself is yet to make a decision.

As of October, no final judgment has been delivered, the stays remain interim, and families continue to live under demolition notices while the courts keep extending dates without arguments being heard.

The result is a cycle of endless adjournments. Families forced to appear in court, only to be handed another extension without resolution.

For them, the stay has not lifted the danger—it has only stretched it out.

As Sarwar Khan, who runs a shop in Batla House, put it, “We are living under demolition notices that never go away. Every date is just another delay, and every delay keeps the bulldozer’s shadow over our heads.”

Decades Of Proof

Among those fighting to save his home is Sayeed Nasir-ul-Hassan, 75, a retired DDA employee, whose own life story shows the depth of this contradiction: a man who once worked for the very authority that now seeks to demolish his home.

Hassan said his family’s house was built by his mother, Khatija Begum, long before the authority was formed in 1957.

Their home appears in the DDA’s layout plan from the 1980s. Hassan said that a survey and sanction plan had included the house in 1982, and the family had been paying property tax since 1983.

Hassan questioned how the authorities could now suddenly claim the land belonged to them, asking, “Where was the DDA all these years?”

He pointed out the irony of having worked for the same authority now threatening his home.

Drawing on his insider’s knowledge of how records are kept, he said he had shown officials every kind of proof—including survey records and tax receipts from 1983, which he also showed us, yet they refused to acknowledge them.

“It is almost laughable,” he said. “Even when I show them the documents, they don’t want to see. Still, we are being treated like liars.”

Hassan lives with his three sons, a daughter, their spouses and children—three generations under one roof. The house, he said, carried their entire family history, where he had been raised, raised his own children, and where now his grandchildren were growing up.

“And now there is fear that one day everything will be destroyed,” he added.

The demolition threats and the uncertainty around the court hearings have eroded his faith in the system.

“One day they paste a notice, then give a deadline, then suddenly there is a stay,” said Hassan. “We are dragged from one court to another while living in constant fear. Even though we have everything, it feels like we have nothing.”

His frustration spilt out as a final question. “How can a government stand so confidently without any evidence, while people like us, who have spent our whole lives here and have every paper to prove it, are left terrified and helpless? Tell me, where is the justice in that?”

Living in Dread

Hassan’s despair is echoed by others in Batla House, who say that even when they hold bundles of documents in their hands, the notices and threats keep coming.

Among them is Mohammad Shakir, 69, who lives in the house his father built in the 1970s. For him, the red cross painted on his wall was the erasure of everything his family had built and preserved for more than half a century.

Shakir said his father first laid the foundation of the house in the early 1970s, and since then, the family has lived there continuously, adding to it floor by floor with whatever savings they could manage.

Over the years, he said, they have preserved every possible record the state ever required—including bills from the municipal water supply from 1984, which he still keeps carefully in files. Even today, he said, the family continues to pay the same bills, proof that the government has long recognised their home and collected revenue from it.

Yet, despite this, the DDA marked his home as an encroachment. The contradiction, Shakir said, is unbearable.

“For decades, we have paid their bills, their taxes, their charges, and today they tell us this land does not belong to us?” said Shakir. “How can the government still take away the only roof we have left?”

The notice has left his family living in constant dread. Shakir explained that he raised his children in this house, where they have celebrated milestones and mourned losses. To be told now that they have no right to it has made him question not just the government’s motives, but the very meaning of belonging.

“It feels like they are telling us that our lives, our memories, our struggles mean nothing,” he said. “That everything can be wiped away in a single stroke, no matter what we hold in our hands to prove otherwise.”

A Minority Within a Minority

The sense of fear runs through every lane in Batla House, but for some, it is also mixed with a profound sense of isolation. Balbeer Singh, 65, the only non-Muslim among the 52 families in his khasra who have received demolition notices, said he feels both targeted and invisible.

His home, built decades ago, according to the property documents dated 1971 that he showed us, by his father Hari Singh, shelters fifteen family members—his three brothers, their wives, children, and grandchildren—all living together under one roof.

Singh recalled the day the notice came as one of the darkest of his life. He was at his vegetable stall when his wife called, crying so hard that he thought someone in the family had died. When he returned, he saw the red cross splashed across their wall and a notice pasted on it.

Because he cannot read, he turned to his neighbours to ask what it meant. That was when he learned the DDA had ordered them to vacate.

“My whole body shook,” he said. “Tears came into my eyes. This was my father’s house. Everything we have is inside these walls. How can they take it away like this?”

For Singh, what has followed has been a cycle of torment. The family, like others in Batla House, has faced repeated demolition threats, each one forcing them into a new round of panic.

First, the officials came and marked the houses. Then notices arrive with deadlines. Then, residents rush to lawyers, running from one office to another, collecting documents. Then comes the waiting for hearings in lower courts, in the High Court, in the Supreme Court.

“We go from one court to another, and still there is no final answer,” Singh said. “One day there is a stay, the next day another notice comes. Every few weeks, it feels like our lives are put on trial again.”

The uncertainty, Singh said, is worse than anything else. His family spends their days in fear, their nights sleepless. His wife has stopped eating properly. The younger children in the house, he said, ask questions the elders cannot answer: “Will the bulldozer really come?”

“What can we tell them?” Singh asked. “We ourselves don’t know if tomorrow they will come with machines and throw us on the street.”

(Masrat Nabi is an independent journalist who reports on politics, gender and human rights.)

Get exclusive access to new databases, expert analyses, weekly newsletters, book excerpts and new ideas on democracy, law and society in India. Subscribe to Article 14.