Agra: On 7 August 2023, teachers from Uttar Pradesh (UP) who were recruited under a scheme to modernise madrassas nationwide, staged a demonstration to draw attention to their demands from the union and state governments.

During the protest at Lucknow’s Eco Garden, they said an honorarium for teachers under the scheme had not been paid for periods ranging from six years to 10 years, just before the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) government assumed office at the Centre.

Just ahead of the general elections in 2014, then prime ministerial candidate Narendra Modi told a television channel that children of Muslims who hold a Quran must “have a computer in the other hand”. In 2019, the union government also announced that madrassas would be inked to mainstream education systems through training of madrassa teachers.

Sarfuddin Ansari, 35, had come from Bareilly district, 250 km north-west of the state capital. During the course of the protest, Sarfuddin fainted. After a few minutes, he regained consciousness and resumed shouting slogans, demanding the pending salary, before fainting again.

Upon regaining consciousness, Ansari pleaded with police personnel standing nearby, with folded hands, asking them to kill him. “I can be free from this life,” he said.

The English teacher said he had been suffering from depression for the past several years, and was unable to send his children to good schools. “I want to die here because I have no reason to go back home,” he said, bursting into tears. “Kill me, sir.”

The protesting teachers, about 2,000 in all, had been appointed to teach ‘modern’ subjects to madrassa students, including Hindi, science, mathematics, social studies and English. They were appointed under the central government’s madrassa modernisation scheme launched in 1993.

Neither the union government nor the UP state government has paid their shares of these teachers’ salaries since 2013, and payments to the teachers appointed under the scheme in UP stopped during Yogi Adityanath’s first term as chief minister.

Some payments have been pending since 2013—that is, for the past 10 years—while some teachers have been working without the honorarium since 2017.

According to a committee of teachers formed to air their grievances and seek redressal, a total of 21,546 teachers were appointed to 7,442 government-aided madrassas functioning under the UP government’s minority welfare and waqf department.

At the protest, the teachers said many of them had been diagnosed with depression and heart ailments, while most said they faced acute financial stress due to non-payment of the honorarium for many years. Most had taken loans, anticipating arrears of their honorarium, and had found themselves buried in debt totalling lakhs of rupees.

The madrassa teachers said they did not have resources to pay for medical expenses for themselves and their families, even as some family members died due to bad health, and of Covid-19 earlier. Without their dues from the government, many were giving extra tuition for countless hours to make ends meet while a few said they had to do wage labour and farming to run their households.

Sheo Prakash Tiwari, deputy director in the state’s minority welfare department, said that on 10 November 2023, the union government announced that the madrassa modernisation scheme, titled the Scheme for Providing Education to Madrassas and Minorities) had approvals only till the end of the financial year 2021-22. He said all funds received from the union government until 2021-22 had been distributed.

“Meanwhile, the Uttar Pradesh government has constantly given additional state share to madrassa teachers over the past years,” Tiwari told Article 14. “However, after the order from the Government of India to cancel the scheme, the additional state share will also not be given.”

He said that on several occasions, the state government had written to the Union government seeking release of funds for the pending honorarium.

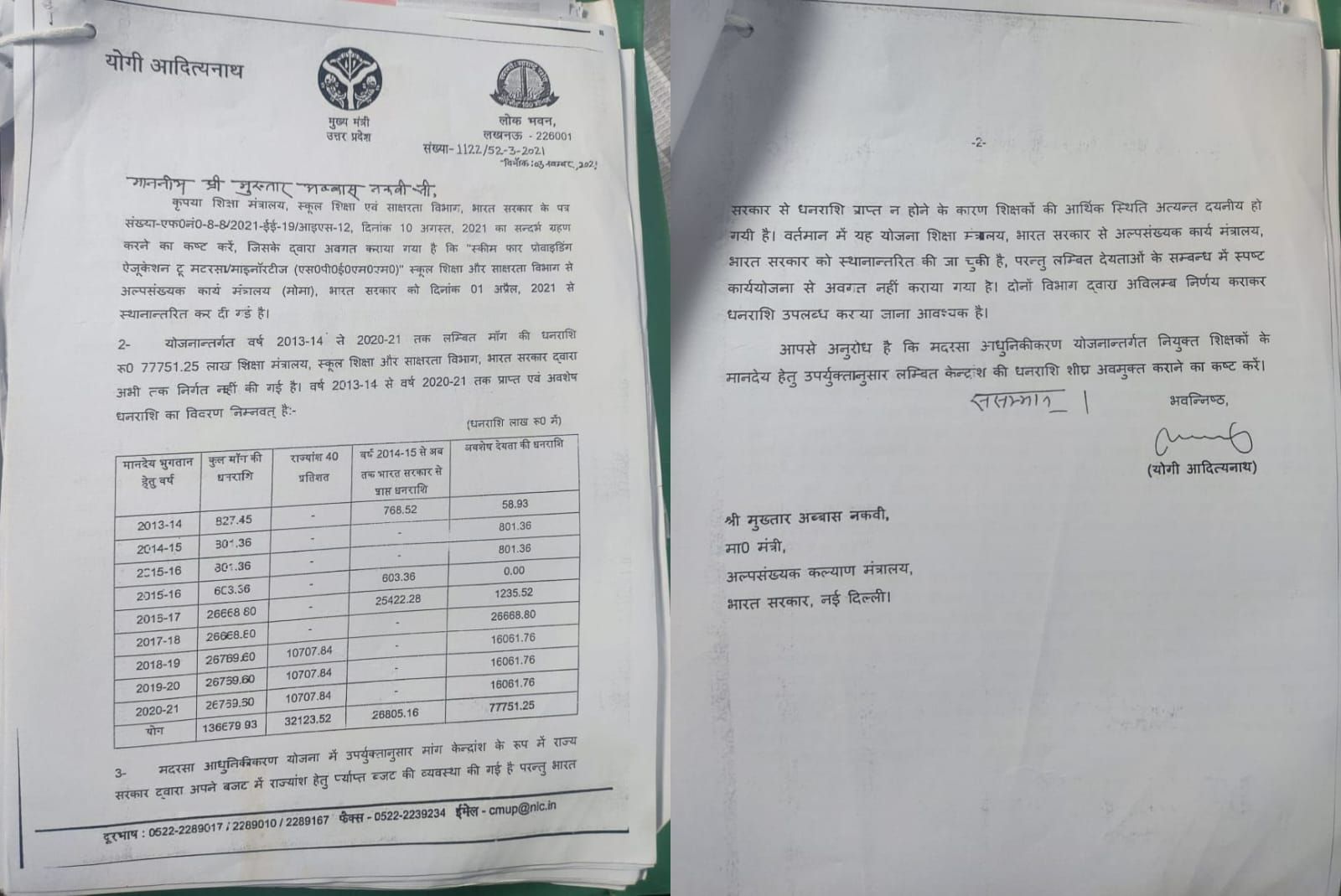

The chief minister had also sent letters, including to union ministers. In a letter on 3 November 2021, Adityanath wrote to the union government requesting the release of pending honorariums from 2013 to 2021. The letter stated that the pending honorariums totalled Rs 77,751.25 lakh at the time, or Rs 777 crore.

“No response has been received from the Government of India in this regard,” Tiwari said.

The Scheme To Modernise Madrassas

To draw children from minority communities into the mainstream, the union ministry of education launched the madrassa modernisation scheme under the ‘national policy on education’ of 1986. (A programme of action in 1992 in pursuance of the 1986 policy on education stipulated a centrally sponsored scheme on modernisation of madrassa education.)

Modern subjects including Hindi, English, science, mathematics, and social sciences would be taught in religious educational institutions such as the Dar-ul-Uloom and madrassas, the scheme envisaged.

In 2008, the government expanded the scheme, renaming it the ‘scheme for providing quality education in madrassas’ (SPQEM). Under the scheme, teachers’ monthly honorarium was fixed at Rs 6,000 for graduates and Rs 12,000 for postgraduates. In 2021-22, the union ministry of education handed over the scheme to the union ministry of minority affairs.

In 2016, the UP government under then chief minister Akhilesh Yadav announced that it would pay an additional Rs 2,000 and Rs 3,000 to graduate and postgraduate teachers respectively, taking their total honorarium to Rs 8,000 and Rs 15,000 respectively.

Incidentally, the incumbent UP government did not reverse the 2016 decision, and madrassa teachers in the state have continued to receive this additional state share of Rs 2,000 and Rs 3,000 (for graduates and post-graduates respectively).

In 2018, the central and state governments had decided to split the costs, with the Union’s share fixed at 60% of the honorarium. UP’s teachers have received neither the 60% Union government share of their honorarium nor the 40% state government share of the honorarium, but have received the additional Rs 2,000 and Rs 3,000 announced in 2016.

In Azamgarh and Mirzapur districts, where a special investigation team probe was ordered by chief minister Yogi Adityanath in 2021 after allegations emerged that nearly 400 fake madrassas in these districts were milking the government scheme, this additional state share was also suspended.

In the 2018-2021 period, the annual budget of the Union government for the scheme was Rs 120 crore, growing to Rs 160 crore in 2021-22.

In 2022-23, the budget was reduced from Rs 160 crore to Rs 30 crore and further curtailed to Rs 10 crore for the year 2023-24.

In a letter dated July 2023 to a secretary to the Union government, Ishtiaq Ahmad of a madrassa in Jaunpur wrote that he had been teaching for 10 years without being paid. He had been appointed under the madrassa modernisation scheme in 2007.

Detailing the outstanding honorarium payments, Ahmad said in his letter that the total outstanding honorarium payments due to him were Rs 5,77,423, including the portions to be contributed by the ministry of human resource development or ministry of education, the ministry of minority affairs, and the state government. He sought to be paid the outstanding along with interest calculated at 16% per annum.

Letters from other teachers quoted similar sums as outstanding dues. Viresh Kumar of Barabanki in eastern UP said his total outstanding dues were Rs 9,37,674. Abhishek Pandey of Amethi pegged his total dues at Rs 9,14,333. Rajesh Yadav of Azamgarh said his dues were Rs 8,70,872.

The teachers contend that the total outstanding payments from the Union government to the 21,000-odd teachers of UP is in excess of Rs 750 crore.

The total outstanding payments, including Union and state government shares, was in excess of Rs 1,628.46 crore till 2022-23, the teachers said.

In Sambhal, A Teacher Becomes A Rickshaw Puller

In 2019, while speaking to a television news crew at New Delhi’s Jantar Mantar, Mohammad Aqib, 32, appeared to try to harm himself.

A few hundred madrassa teachers from UP had gathered to protest the non-payment of their honorarium and Aqib was among others who spoke to a news channel. Suddenly, he began to strangulate himself with a handkerchief, but was stopped by other teachers.

Later, Aqib assured journalists that he would not take any drastic measures, but said he had been depressed after nearly two years of working without the honorarium.

Aqib, from Sambhal district in western UP, was appointed in 2014 under the madrassa modernisation scheme to teach mathematics and English to students in Madrassa Faiz-Ul-Uloom, in Shahbazpur Kalan, in Sambhal.

His honorarium payments abruptly stopped in 2017. The father of an infant boy aged seven months, Aqib also cares for his unwell mother who suffers from a damaged liver and needs medicine and oxygen, which cost about Rs 1,500 a week.

“I haven’t had a regular income, so my married sister sends money for her treatment,” he told Article 14. “To survive, I have been working part-time as an autorickshaw driver in a town near my village.”

Aqib, who has a master’s degree and a diploma as well as certificate courses in computers, said he operates the autorickshaw from 2 pm till the evening, after madrassa classes end. “I feel very ashamed when students see me driving a rickshaw.”

Aqib said he was under a great deal of stress and anxiety over a Rs 2 lakh loan from relatives.

It was ironic, Aqib said, that while the Bharatiya Janata Party government at the Centre had propagated the slogan ‘Ek Hath Quran Aur Dusra Hath Computer’ (the Quran In one hand and a computer in the other), those who were teaching mainstream subjects in madrassas were being forced to quit teaching to survive.

A Futile Meeting With Smriti Irani

Sahimullah Khan, president of the Madrassa Modernisation Teachers Association Uttar Pradesh, told Article 14 that he had requested Jagdambika Pal, Lok Sabha MP from Domariaganj in eastern UP, to help fix a personal meeting for the teachers with union minister for minority affairs, Smriti Irani.

According to Sahimullah Khan, Pal met Irani in February 2023 and raised the issue of teachers’ salaries under the madrassa scheme.

Pal reportedly told Sahimullah Khan that the minister had not given him a positive response, and Khan then requested again that the teachers be allowed to meet Irani. On 20 March 2023, Sahimullah Khan (Bahraich), Santosh Pathak (Shravasti) and Abhishek Pandey (Amethi) met Irani in Shastri Bhawan, New Delhi, but came away without a resolution to their grievance.

Meanwhile, on 10 February 2023, Indian Union Muslim League (IUML) Member of Parliament Abdul Wahab introduced a resolution in Rajya Sabha, seeking a special fund for the modernisation of madrassas. The resolution was rejected by a voice vote on 24 March even as the Congress and other opposition parties staged a walkout.

Before the vote, Irani told the upper house of Parliament that the resolution “casts aspersions of inequality” and urged members to reject it. “A new India cannot be broken down on the basis of religion,” she said. “That is why I would request the entire House to unanimously reject this resolution so that we, who are building the new India under the leadership of the prime minister with the support of citizens, can build it on issues of inclusion, equity, and equality.”

‘Only One Meal A Day At Home’

On 7 August 2023, madrassa teacher Arshi Ansari was among those protesting in Lucknow’s Eco Garden, wearing dark glasses on account of a bout of conjunctivitis.

Her seven-year-old daughter had been admitted to a government hospital in Kanpur six days earlier, diagnosed with encephalitis. “I first took her to a private hospital, but due to the high costs, almost Rs 7,000 per day, we decided to move her to a government hospital,” she told Article 14.

Ansari, 29, said she had loaned money from relatives for the treatment.

A resident of Unnao in eastern UP, Ansari was appointed in 2017 under the madrassa modernisation scheme and stopped receiving the honorarium a few months later.

Everyday, she takes a train 70 km either way to and from the Sheikh Ullah Aulia Madrasa in Unnao. The fare is Rs 250 per day.

Arshi Ansari has two children, a seven-year-old daughter, and a two-year-old son.

Ansari’s daughter’s fees at the Iqra Public School in Unnao are outstanding, with a late payment penalty growing every day.

“At present, I am not even able to provide milk for my children,” she said. “Only one meal is cooked at home.”

Ansari’s husband works as a private salesman, while she took up part-time work as a tailor, sewing clothes for women of the locality.

She said she would quit the job in 2024 if the honorarium remained suspended, and work as a tailor full-time. “How long can the teachers continue to teach without a salary?” she asked. “Perhaps this was the intention all along.”

Anant Singh, the media in-charge for a committee of teachers working in the madrassa modernisation scheme, said the UP government should turn the scheme into a state-funded one and undertake to pay 100% of the honorarium. Singh himself gives home-tuition services during the after hours. “We teachers build the nation, we educate the future of the country,” he said, “and today our own family is on the streets.”

He cited the example of a friend who completed his education as a software engineer and took up a job as a teacher under the scheme in 2001, “He is regretting his decision,” Singh said. “For now he is neither an expert software engineer nor is he an established teacher. Despite his education, he is unemployed and stressed.”

Health, Mental Health, Home Finances Hit

Maulana Akhtar Ali, 56, of Ghazipur district told Article 14 that he had been unable to get his daughter married due to lack of funds, and several prospective matrimonial alliances had broken down. “People of the neighbourhood and my relatives taunt me, asking whether I will get her married in her old age,” he said.

Appointed in 2001 under the madrassa modernisation scheme, the maulana, a ‘double MA’ or holding two MA degrees, has not received an honorarium since 2013. He teaches English and Social Sciences in a Mirzapur madrassa, located 100 km away from his home. He lives in a small rented space near the madrassa.

The maulana has two daughters, aged 23 and 21, and three younger boys.

Tearing up repeatedly, Akhtar Ali said he had been unable to afford treatment when his father had a paralytic stroke. He took a loan of Rs 1.5 lakh for the medical expenses, which is still outstanding. His father died in 2021. Later, his wife was diagnosed with a brain tumour and epilepsy.

As a private tutor for English, Mathematics, Arabic and Urdu, he earns Rs 5,000 per month. “It’s not enough money to get my wife treated properly,” he said. An old spinal cord injury he suffered has also been ignored.

Akhtar Ali said that in 2021, the government had ordered a special investigation team (SIT) probe based on the complaint of activist Irshad Ali regarding fake madrassas in Mirzapur and Azamgarh districts, but said he had been denied any information about the investigation by government officials.

In 2021, activist Irshad Ali had used the Right To Information (RTI) Act, 2005, to expose alleged fake madrassas in Mirzapur and Azamgarh. He reportedly showed that 14 madrassas in Mirzapur were fake.

According to Akhtar Ali, in April 2023, about 50 madrassa teachers from Mirzapur visited the SIT office in Lucknow, and an officer had assured that the SIT investigation in Mirzapur would be done as soon as possible.

Akhtar Ali said an investigation team of three members conducted checks in his madrassa only earlier in 2023, but the state share of the teachers had been stopped since 2021.

According to officials of UP’s minority welfare department, the physical verification of madrassas was proposed by the department and executed by teams formed under respective district magistrates. “Each school is assigned a unique code based on its location, type, management and other factors,” said Tiwari, the deputy director of the department. Once admissions are done under the code, the strength of students in the madrassa cannot be changed, and every admitted child is required to have an Aadhaar card, he said.

In some cases, a physical verification was conducted but payments did not resume. A teacher in a madrassa in Unnao district in eastern UP told Article 14 that the district minority officer conducted a physical investigation in the district’s madrassas twice between June and September. “I provided all kinds of documents and related information during the investigations, but the state share was not given,” she said.

She said that during the physical verification, the investigation team took photographs and shot videos of the madrassa, checked the attendance register, details of teachers, and property documents of the structure. A total of 122 students study in her madrassa, but the investigation team registered only 60 students’ names, she said, because the others did not have Aadhaar cards.

Madrassas Have Hindu Students And Teachers Too

An estimated 40% of madrassa students in UP are reported to be Hindus, and 45% of teachers were Hindus too, according to the protesting teachers.

Pankaj Mishra, 34, teaches Hindi at the Madrasa Misbahloom Uloom of Shravasti district. He was appointed on 14 August 2014 and stopped receiving the honorarium in 2017. Along with his two children, he also cares for his parents, grandmother, brother, sister-in-law and their children.

Pankaj Mishra said his brother was currently unemployed, and the responsibility to feed the joint family was on his shoulders. For six months, he has not paid his two children’s school fees, Rs 1,000 per month.

The family cultivates paddy and wheat on their 4 bighas (about 2.4 acres) of land, but have faced farm losses too due to floods.

About 250 poor children study free in the madrassa where he teaches, he said.

He said he occasionally had thoughts of self-harm.

“I want to convert to Islam so that I can become a maulana and get appointed in any madrassa and teach Urdu and Arabic,” he said bitterly.

The family has survived on the free and subsidised foodgrains under the public distribution system (PDS). “The grocer refuses me even salt or turmeric powder,” he said, “because he knows that I have not been able to return the money in the past.”

Mohammad Arif, 32, taught in a madrassa in Basti district of eastern UP and was a regular participant at protests to demand the honorarium. On 5 June 2019, he died after suffering a cardiac arrest.

Arif, who had an MA degree and a B Ed degree, was the only breadwinner at home. He had not been paid the honorarium for 35 months.

He left behind two daughters including one with a mental disability, a wife, his mother and his grandmother.

Vinod Kumar Maurya from Varanasi, another Hindu teacher at a madrassa, said Arif’s family’s financial condition had steadily declined and he had been under tremendous mental stress over not being able to provide for the family.

“Many of our fellow madrassa teachers have died of heart attacks,” said Maurya, adding that many were suffering from depression and many others had just quit their jobs.

BJP Booth-Level Officer Seeks Outstanding Dues

Ratan Kumar Kushwaha, who teaches maths at the Madrasa Darul Uloom Ahle Sunnat Badrul Uloom in Gonda district in eastern UP, said he has served as a booth-level officer for the Bharatiya Janata Party since 2017.

“I made the villagers aware and vote for the BJP,” he said. “I connect the villagers with the party. I inform them about the work, policies, plans and public schemes of the BJP.”

He said he was only fulfilling his responsibility as a party worker,

The 49-year-old was appointed in 2002 as a madrassa teacher under the modernisation scheme, originally in Basti district. Khushwaha, who holds an M Sc degree from Benares Hindu University, has not received the honorarium since 2015.

He tutors children to make ends meet. A paraplegic, he cannot take up labour.

“We are coming to teach without a salary only for the sake of the poor children,” he said. “Village students come to learn modern subjects like Hindi, English, math, science and social studies. They study religious subjects through tuitions with a maulvi.”

Two of his co-teachers stopped coming to teach, he said, adding that he would continue because 200 children’s future depended on it.

‘I Will Sell Tea To Make Ends Meet’

Haseena Bano, appointed under the madrassa modernisation scheme in 2017, was emotional as she recounted taking a loan of Rs 3 lakh from relatives to get her two daughters married. Haseena is owed 72 months of honorarium.

The 45-year-old Haseena Bano from Jaunpur district in eastern UP has an MA degree, and four children. One son, aged 19, was recently admitted into an engineering course in a government college in Kanpur, for which she took an additional Rs 1.5 lakh from a bank.

“I have taken loans of more than Rs 5 lakh so far, for my children,” she told Article 14. “I don't know how I will be able to repay this in the future.” She said if the honorarium payments are not made, she would have to sell her home to repay the loans.

Haseena Bano's husband, a tailor in Mumbai with an income of Rs 10,000-Rs 12,000 per month, sends some money home after his own expenses.

She said if the government wished to abolish the scheme, it should say so and take the step. “Do it today, but pay our outstanding honorarium. We will sell pakodas or tea to make ends meet,” she said bitterly.

Union, State Governments Ignore Repeated Protests

Ashraf Ali, the UP state president of a committee of madrassa teachers appointed under the scheme, said almost all the teachers had participated in innumerable protests in Delhi, Lucknow and district headquarters from 2017 onwards, but in vain. “The government is continuously ignoring our demands and protests,” he said. “We have given a memorandum several times in the last several years to the prime minister's office, the President's secretariat, and the Union home ministry to make them aware of our problems.”

Ashraf Ali said that the madrassa teachers had continued to be associated with the scheme because they had hoped that the Union government would take cognizance of their pleas and pay their outstanding dues and re-energise the scheme.

Ashraf Ali said only opposition leader Asaduddin Owaisi of the All India Majlis-e-Ittehadul Muslimeen (AIMIM) had raised the issue in the Lok Sabha. Lal Bihari Yadav, a Samajwadi Party member of the UP Legislative Council, drew attention to the teachers in the UP Vidhan Sabha.

(Shivani Chaudhary is an independent journalist based in Agra.)

Get exclusive access to new databases, expert analyses, weekly newsletters, book excerpts and new ideas on democracy, law and society in India. Subscribe to Article 14.