Kolkata: Ngalchangpa Mate, who claims to be a ‘global citizen’ and ‘woke millennial’ based in New Delhi, joined Twitter in May 2023. The first tweet from his account was on 6 May, three days after violence broke out in the north-eastern state of Manipur between the majority Meitei Hindus and the Kuki tribals.

The post was a retweet of Sweden’s Uppsala University professor Ashok Swain’s tweet claiming that the people in the video were ‘tribals in Manipur’ escaping to neighbouring states due to ‘violence by non-tribals’.

In subsequent weeks, the handle posted more than 150 tweets, all of them on the violence. All his tweets amplified the Kuki point of view against the Meiteis. The account gained more than 1,400 followers in just about 20 days.

While Mate is a Kuki surname, nothing more could be known about the person behind the account. Most of the posts were retweets, some from accounts of recognisable individuals and organisations that voiced concerns for the Kuki people, and others from handles that became active only after the outbreak of ethnic violence on 3 May, like Mate’s own handle.

The 80-odd handles that Mate follows include several that started tweeting on or after 3 May.

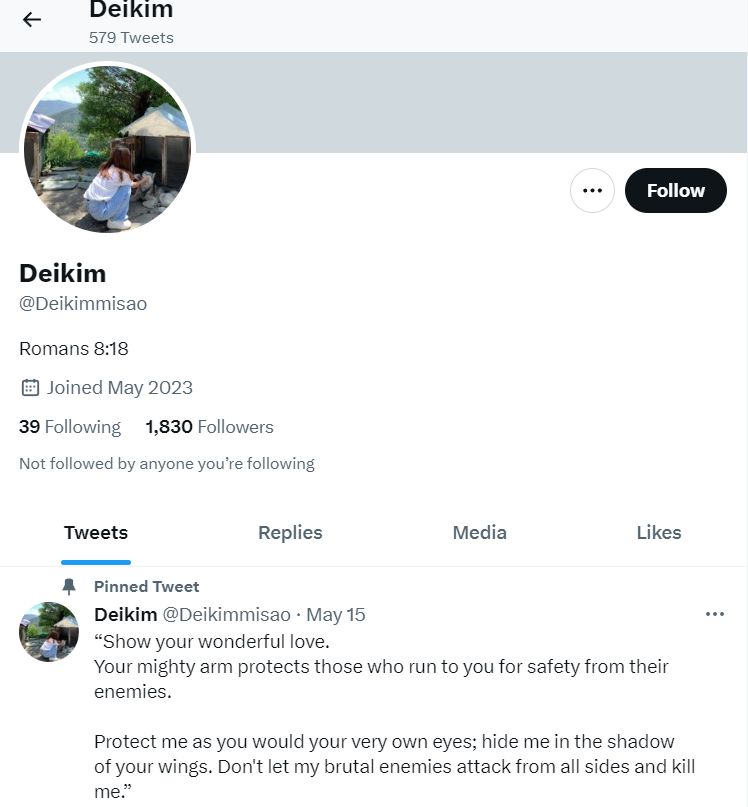

One of them going by the name Deikim, which posted its first tweet at 6.29 pm on 3 May, a few hours after violence broke out, posted another 500 tweets over the next 26 days, gaining 1,800 followers.

The first tweet from Hebron was on 4 May, sharing a Change.org petition demanding President’s Rule in Manipur. The handle posted another 500 tweets over the next fortnight. Chin-Mizo-Kuki-Zomi (Oneness) sent out its first tweet on 4 May and another 700 riot-related tweets over the next two weeks, all of them highlighting the Kuki side of the story of the violence.

Mate was also followed by newly created handles: Harry Misao, which posted 50 tweets since 11 May; Manga Changsan, which posted 116 tweets since 4 May; Aalhing Kilong, which posted 90 tweets since 17 May; Ruth Haokip, which posted 45 tweets since 7 May; and Haokip Lamshi, which posted 40 tweets since 18 May.

These are among the scores, or hundreds, of Twitter handles that became active after the outbreak of ethnic clashes. They solely served the purpose of spreading stories of Kuki victimhood. None of these handles specifically identified the persons using them.

While internet services were suspended in Manipur on 3 May soon after violence broke out and remained so in most parts of the state for a record 30 days, these handles continued to spread propaganda, vilifying one side.

More than 80 persons have been killed in Manipur in ethnic clashes that began on 3 May, continuing in various degrees till 24 May. On 28-29 May, ahead of a visit by union home minister Amit Shah, fresh clashes erupted. Militants reportedly set fire to many houses in Serou and Sugunu, villages located about 20 km east of Churachandpur.

About 39,000-40,000 people were rendered homeless due to vandalism and arson of properties. The government clamped section 144 of the Code of Criminal Procedure (CrPC), 1973 prohibiting public gatherings of more than four persons, but the conflict did not de-escalate. Chief minister N Biren Singh has claimed that 40 Kuki militants have been killed in action by security forces.

At the end of his four-day visit, Shah on 1 June announced the formation of a probe committee headed by a retired high court chief justice. “The governor of Manipur will head a peace committee with members of civil society,” he said.

Meitei Hindus make up over half of the state’s 28.55 lakh population according to the 2011 Census. Manipur, one of India’s smallest states with 0.23% of India’s population, also has a sizeable population of predominantly Christian Kuki tribals and various Naga tribes, also mostly Christian.

Even as activists and intellectuals called for urgent action to narrow the rift between the two communities, these Twitter handles demonising the other community polarised people sharply.

Pro-Kuki handles appeared to be more numerous, but there were several handles representing the Meiteis as victims too. These handles vilified the Kukis, blamed them for the violence, and linked them with illegal immigration and drug and weapons racket.

Peace, an account that posted its first tweet on 4 May, tweeted more than 500 times subsequently. Some of its tweets showed alleged armed Kuki militants, others branded Kukis as ‘refugees’ and infiltrators. The account of Indigenous People's Front of Manipur, an unknown organisation that the account claims is a ‘political organisation to protect and preserve the indigenous people of Manipur’, was also created in May, and started retweeting posts blaming the Kukis.

There is a long list of such pro-Meitei accounts created in May— Sylvia Ngangom posted more than 40 tweets since 4 May, Meitei by blood became active on 5 May and posted over 70 tweets, Walmart Banana posted more than 50 times since 3 May, Noni Loitongbam posted more than 80 tweets since 4 May, Malem posted more than 200 tweets since 5 May; Gisa Rose made more than 200 tweets since 3 May, Chanulembi tweeted more than 250 posts since 3 May, Leichil posted over 90 tweets since 11 May, Heikru Maru tweeted over 200 times since 11 May and Sonia Hydrogen posted over 200 tweets since 4 May.

Paokholun Hangsing, a professor at the library and information science department at the North-Eastern Hill University in Shillong who is a Kuki by ethnicity, said that the Kukis had to depend on social media to amplify their voice and counter misleading claims because they have a negligible presence or influence on the local as well as the national media organisations based in metro cities.

He alleged that video clips of Meiteis looting and burning down Kuki houses in Imphal were passed off as Kukis burning and looting Meitei houses, by muting the audio.

“Somebody who knows Manipur can easily identify the attackers by their dresses and the language they speak,” he said. “Unfortunately, most mainstream and national media cannot tell the differences between the two communities and are unaware of the deceptions.”

A Kuki scholar, who did not want to be identified, said that not only were ‘Kukis displaced by violence’ forced to create anonymous handles but other pre-existing organisations also opened social media accounts to “highlight the truth”. The scholar cited the examples of Manipur Tribal Forum, Delhi and Kuki Students’ Organisation (KSO)’s Mumbai, Pune and Guwahati chapters, whose accounts started operating after 3 May.

The Ethnic Violence In Manipur

There is no reliable estimate of which of the two communities suffered the most.

Imphal-based journalist Paojel Chaoba wrote in an article that Meiteis living in the hill districts and Kukis living in the valley districts were the worst sufferers. A delegation of all of the state’s 10 Kuki MLAs that met home minister Amit Shah in New Delhi on 15 May reportedly wrote in their letter to him, “There are no tribals left in the Imphal valley. There are no Meiteis left in the hills.”

The use of the word ‘tribal’ referred to the Kukis, for tribal people belonging to Naga ethnicity did not face any hostility during the riots.

The violence started on 3 May afternoon, soon after the conclusion of a ‘tribal solidarity rally’ organised by the All Tribal Students' Union, Manipur (ATSUM), a platform that includes both Nagas and Kukis. The ATSUM rally was held to protest the Meitei community’s “persistent demand” to be included among the scheduled tribes ( ST) and “the support to this by valley legislators”. ATSUM said their goal was to “collectively protect the tribal interests”.

Most accounts pointed to the beginning of violence in the Torbung locality in Churachandpur, a town in the south-western part of the state, after news spread (read here and here) that some Meitei youths had desecrated a gate of the Anglo-Kuki war memorial built to commemorate the Anglo-Kuki war (1917-19). The memorial is in Leisang, about 4 km from Torbung. It did not take time for the violence to spread to other parts of the state.

A number of political observers and commentators attributed the violence to growing tension between the communities over the past few months and the state’s BJP chief minister N Biren Singh’s alleged role in aggravating the tension.

The violence triggered a debate over alleged bias in media coverage.

On 8 May, three Manipur-based journalists’ organisations, the Editors Guild Manipur (EGM), All Manipur Working Journalist Union (AMWJU) and Manipur Hill Journalists Union (MHJU), made a joint appeal to “fraternal media practitioners from mainland India and abroad to do justice in your reporting by balancing your stories.”

The statement noted that “forces within both the parties in conflict” were trying to bring about a fracture between the two communities “for political mileage, personal vendetta and many other factors including the drug trade and turf control”. It urged journalists from outside the state to “remember the role of certain media in Rwanda that sparked an unwanted genocide decades ago.”

A Propaganda War Breaks Out Online

“Hunting, torturing, slaughtering, raping and then killing Kukis, now looting their properties. Dear Meitei have some shame!” read a post by CHIKIM te AWGIN on 18 May, with accompanying photos showing people on a road carrying furniture that was allegedly looted from houses that had been vandalised.

The first tweet from the account was on 7 May, four days after violence started. It posted more than 600 tweets over the next 12 days and gained more than 2,000 followers, many of them similar pro-Kuki accounts activated during the days of the violence: Pj Rophael Guite, Hauneinieng Zou, Joycee Khaute, Kam Thadou, Mangminlen Haokip, Lain Vaiphei, Helim Mate, Kim Khuptong, SL Boilhing, Lamneivah Mate, and the, PinkyNgah Khongsai and Boicy Khongsai.

Unlawful Lawyer, which claimed to do ‘journalism without fear and favour’, based in Bangkok, Thailand, posted more than 150 tweets since its first post on 5 May. Like all pro-Kuki accounts, it tried to counter some of the key issues that the state’s political leadership, including chief minister Singh and different Meitei-interest groups, had levelled against a section of Kukis— illegal immigration resulting in change of demography and involvement in poppy cultivation and cross-border drug smuggling.

One of its tweets claimed the internet shutdown in Manipur’s hill districts had disallowed tribals’ narrative to be shared online, while Meiteis were ‘spreading false information and changing narratives’.

These accounts kept retweeting posts by recognisable Kuki politicians including Paolienlal Haokip of the BJP, Lamtinthang Haokip of the Congress and former BJP Manipur spokesperson H S Benjamin Mate, Kuki intellectuals like Kham Khan Suan Hausing of Hyderabad University, Thongkholal Haokip of Jawaharlal Nehru University and Paokholun Hangsing of North-Estern Hill University, apart from Kuki organisations such as the Kuki Students’ Association (KSO).

Many people behind such accounts on shared material tweeted by others. Thaokip posted the first tweet on 14 May, and a whopping 3,000 more tweets over the next six days, almost all of them retweets.

The account LG made more than 1,500 retweets since the first one on 6 May. BoiMyien retweeted over 1,700 posts since 10 May, sometimes adding comments, hashtags or tagging other handles. Kaang Kaang only retweeted—190 times since 3 May. Mawinu either simply retweeted or quoted tweets adding hashtags—more than 350 times since 5 May.

In the case of the pro-Meitei accounts, apart from the ones newly created in May, there were several Twitter handles created earlier but idle until violence broke out.

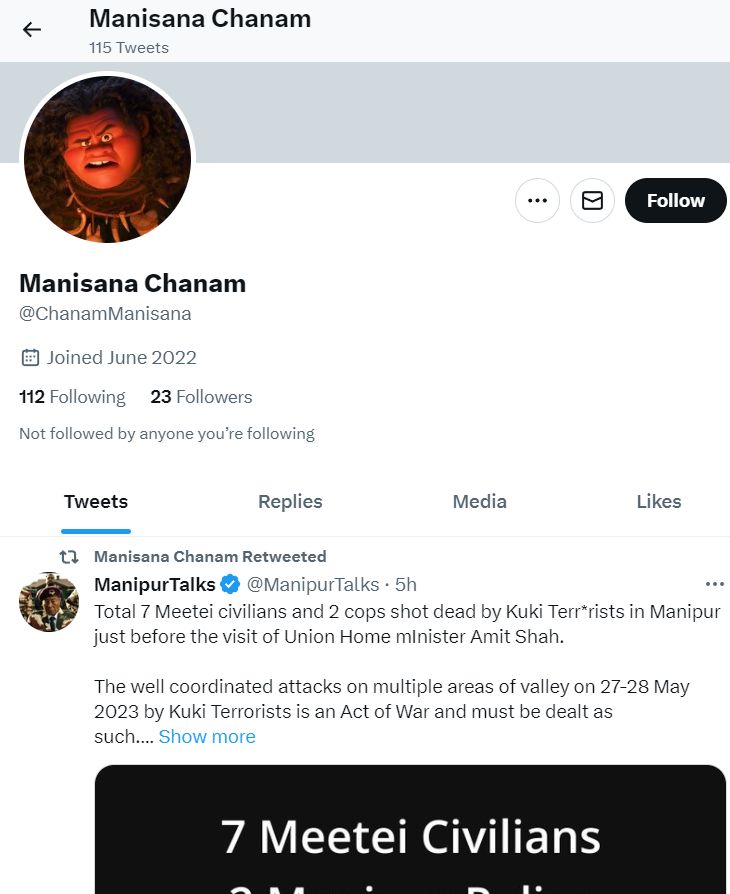

“Illegal kuki immigrants spreading propaganda to create chaos among other indigenous people and not even satisfied after killings and burning hundreds of houses,” said a 5 May post from the handle Manisana Chanam. The account was created in June 2022 but the first tweet was posted on 5 May, followed by more than 60 tweets over the next few days.

“The minority community Meiteis in Churachandpur running away to save their lives because their houses are burn to ashes by the Kuki tribals. What are their faults?” said a tweet from the handle Save Manipur posted on 4 May that was retweeted over 400 times. The account was created in December 2022 but the first tweet was posted on 4 May. It posted about 100 tweets since then, many of them shared dozens of times.

Tomba, an account created in February 2022, started tweeting only on 14 May and posted more than 75 tweets since then, all highlighting the Meitei side of the story. 光るHikaru’s account was created in December 2022 but its first activity was on 4 May when it posted 24 tweets blaming the Kukis. It became inactive thereafter, but its first tweet was shared more than 500 times.

The account MEITEI THOUNA was created in July 2020 but the first tweet was posted on 3 May and more than 350 tweets were posted since. Khumanthem Lamyanba, an account created in October 2022, posted the first tweet on 4 May and another 40 over the following days. Wattaba Thongam, which joined Twitter in October 2021, posted its first tweet on 3 May and another 80 tweets over the next couple of days, before becoming inactive again.

Thoudam Yoihenba, whose account was created in 2020 and bears no photo or information, was lying idle since posting two tweets on August 21, 2020, protesting the JEE exam during the Covid pandemic. It posted more than 180 tweets—mostly retweets—between 4 May and 20 May, all related to the violence, blaming the Kukis.

Besides, multiple pro-Hindutva Twitter handles helped amplify the Meitei propaganda. For example, Manoj, Ritu #सत्यसाधक and SK considered the violence a battle between Hindu Meiteis and Kuki Christians in which the Hindus must be defended.

Propagandist Players And Intentions

One interesting aspect of the propaganda war was the role played by D-Intent Data, which claims to be a ‘propaganda and fake news detection centre, a news data research organisation, focusing on neutral fact-checking and intent analysis.’ The handle, active since July 2022, debunks misinformation on global and Indian affairs.

Its fact-checking on Manipur, however, was winged with bias against the Kukis. They claimed to have busted ‘Kuki bot accounts’ on Twitter but remained silent on the presence of similar, newly created pro-Meitei handles.

They put the Kuki share of Manipur’s population at 30%, without citing any source. The 2011 census put the state’s total tribal population at 40.9%, which includes the Nagas, one of Manipur’s major ethnic groups.

In a tweet, sharing a video of a group of Bnei Menashe soldiers in Israel, D-Intent wrote, “Illegal migrant Kukis from Myanmar have joined militant groups in Manipur and are now openly brandishing high-tech weapons and targeting the Meitei community. Their videos can be found on social media.#ManipurViolence.”

After fact-checking website Alt News pointed out that videos from Israel were being passed off as those of Kuki militants in Manipur, D-Intent lashed out at the fact-checking portal in a thread, calling Alt News ‘a propaganda website.’

For ‘debunking’ information regarding the charred body that several accounts claimed was of a Kuki woman, D-Intent simply took Manipuri child environment activist Licypriya Kangujam’s Twitter post at face value, without any attempt to verify the claims of Kangujam, who is a Meitei. This was despite Kangujam’s account having posted a series of anti-Kuki tweets.

In another tweet, they wrote, “Kuki IT cell and #Fake Pakistani accounts are spreading videos with false claims and most of them are fake,old or computer-generated.” In another tweet, they said, “It is about illegal migrants from Myanmar posing as Kukis and occupying protected land & misusing the ST status while the Meitei community was deprived of its rights.”

D-Intent did not respond to questions sent by Article 14 via Twitter asking to clarify their method of fact-checking in these specific cases.

Samarjit Hawalbam, an Imphal-based advocate and former secretary of the high court bar association of Manipur, suspected that the Kuki propaganda efforts “may have the backing of Kuki drug mafias who played a key role behind this violence in order to create a safe haven” for their operations. He said he was unaware of any such campaign by the Meiteis.

“This is likely being done by Kukis currently living outside the state. Such efforts need to be thoroughly investigated,” he told Article 14 over the phone.

Hangsing, on the other hand, pointed out that the Imphal-based state media sphere is bereft of any Kuki representation and this is being used to propagate the narrative that Kukis are immigrants. Hangsing told Article 14. “These very media houses and journalists, in turn, serve as the ‘sources’ for the mainstream or national media . Therefore, the mainstream media is usually misinformed and reduced to an amplifying mouthpiece spreading the narratives intended to malign the Kukis.”

According to him, it is under such circumstances that Kukis who were “driven out of Imphal” took to social media spaces. He said he would not be surprised if more Twitter handles are created in the coming days, for social media emerged as the only medium for “marginalised and victimised Kukis” to offer an alternative narrative.

Veteran Imphal-based journalist Pradip Phanjoubam, editor of Imphal Review of Arts and Politics and a former editor of Imphal Free Press, one of the most widely read newspapers in Manipur, told Article 14 that the point of Meitei numerical domination in Manipur’s major media houses is true but the allegation of the entire coverage being biased may not be the case.

“I am not sure if their entire coverage can be called biased,” he said. “Currently, the Imphal-based media is not being able to visit hill districts like Churachandpur and Kangpokpi due to various risk factors.” This may be one reason why coverage has been Imphal-centric, said Phanjoubam, who is a Meitei by ethnicity.

He, however, said that the allegation of the national media’s coverage to have been influenced by the narrative pushed by the Meiteis is incorrect. “Journalists from outside the state worked independently, visited both the valley districts and the hill districts and spoke to all sides. Their coverage has not been biased,” he said.

Nevertheless, four Kuki student organisations on 26 May issued a joint statement announcing a ban on ‘all valley-based media outlets’ in general, and newspaper The Sangai Express (whose owner, pro-government independent MLA Nishikant Sapam has been vocal against the Kukis) and local TV news channel ISTV in particular, accusing the Imphal valley-based media organisations of having become “a propaganda machine for the state government”.

These organisations, the Kuki Students’ Organisation (KSO), Hmar Students’ Association (HSA), Zomi Students’ Federation (ZSF), Mizo Zirlai Pawl (MZP), appealed to the ‘general public to cooperate with their ban by reporting “all cases of their presence in our land,” meaning the Kuki-dominated hill areas.

The three journalists’ organisations criticised the move in a joint statement, stating that “a blanket ban on all media persons or media houses from the valley area indicates a deeper conspiracy rather than addressing the issue.”

(Snigdhendu Bhattacharya is an author and independent journalist based in Kolkata, writing on politics, policy, environment, human rights, data, history and culture.)

Get exclusive access to new databases, expert analyses, weekly newsletters, book excerpts and new ideas on democracy, law and society in India. Subscribe to Article 14.