New Delhi: Even as the third wave of Covid-19 unfolded, nearly 6,000 Indian non-governmental organisations (NGOs)—many of whom perform critical relief work that the government cannot or will not—were on 1 January 2022 barred from receiving funds from foreign sources.

Nonprofits are starved of funds at a time when the poorest 20% of Indian households—who had not witnessed an income decline in 35 years since 1995—experienced a halving of income in 2021 compared to 2016, the Indian Express reported on 24 January 2022, quoting the latest data from the People’s Research on India’s Consumer Economy (PRICE), a Mumbai-based think tank.

The new year brought uncertainty and panic to nonprofits, as the ministry of home affairs refused to renew licenses under the Foreign Contribution (Regulation) Act (FCRA) 2010, the law that regulates how nonprofits in India receive and use foreign funding.

The decision has come in the aftermath of the Foreign Contribution (Regulation) Amendment Bill, 2020, which amended the FCRA in September 2020 and provided for stricter requirements and regulations for NGOs to receive foreign donations.

These restrictions, claimed to enhance “transparency”, as the government put it, are quite the opposite in effect: either vaguely worded or minutely specific and allow officials greater subjective interpretation and opacity.

They include a ban on transferring foreign funds from one NGO to another; lowering the ceiling on use of such funds for “administrative expenses” without specifying the definition of the term; introducing other undefined terms allowing subjective interpretation by government; and requiring NGOs to receive foreign donations only through one branch of a state-run bank.

From all accounts, as we detail later, registrations are cancelled in casual fashion, without adequate warning, and accounts are frozen as a first resort as opposed to the last. The status of India’s civic space, by one estimation, went from “obstructed” in 2019 to “repressed” in 2020.

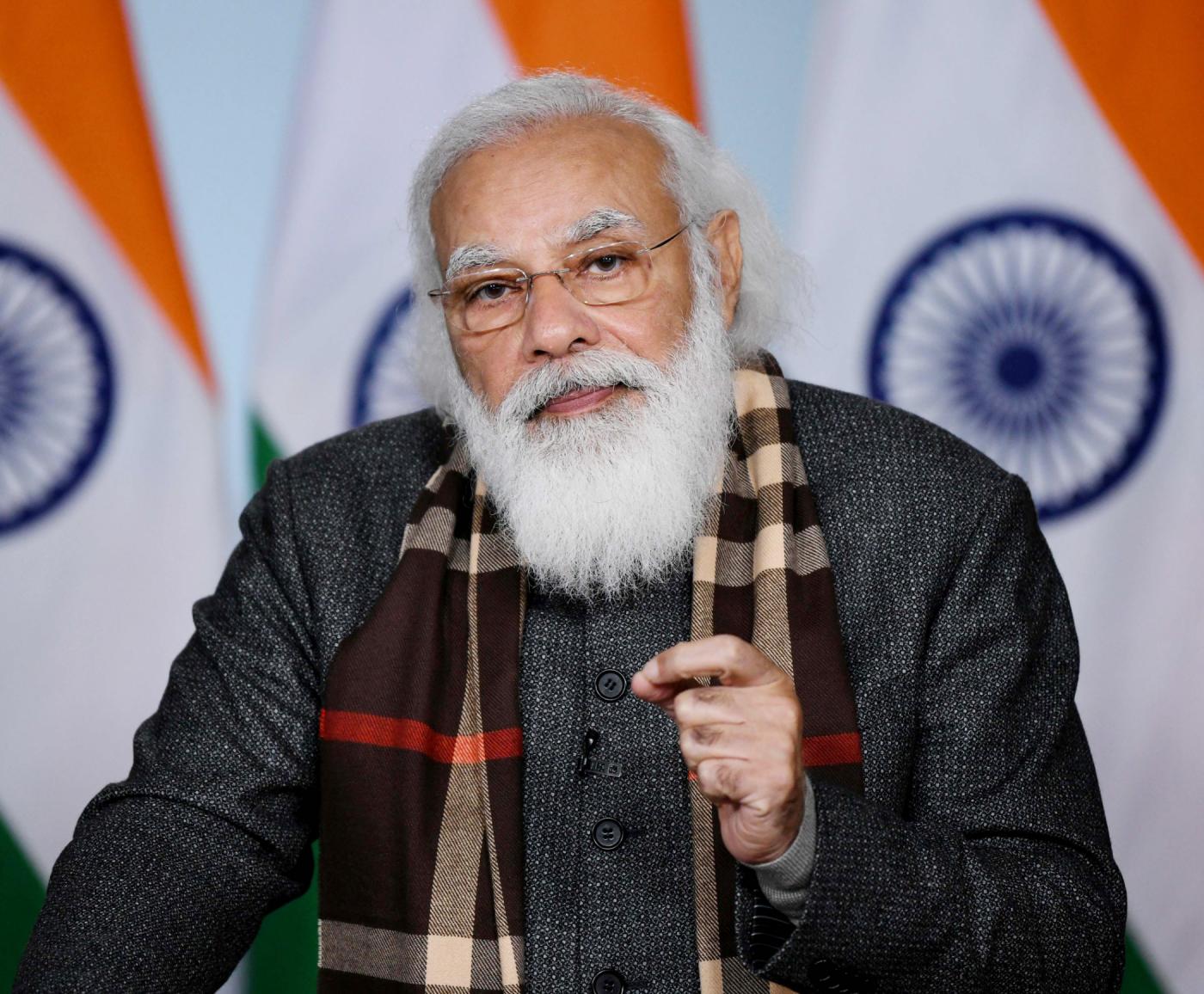

The tightened regime for NGOs fits Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s track record of sweeping suspicions and allegations against them, reflected in the fact that the first move against them began a week after he took office in 2014.

As many as 16,754 NGOs have been barred from accessing foreign funding since 2014, according to home ministry data: 80% of the licenses revoked since 2011 can be attributed to the Modi government.

The funds raised by Indian NGOs via the FCRA fell 87%, from Rs 16,490 crore in 2018-19 to Rs 2,190 crore in 2019-20, the latest year for which data are available.

“My friends, you have voted me to rid the country of these diseases,” Modi said in 2016, by which time a gradual, government squeeze on nonprofits had begun. His government’s views are reflected in phrases such as “national security”, “anti-national”, “anti-development” and “foreign powers.. interfering with internal polity”, in reference to NGOs.

The contradictions in the government’s moves were made more obvious by other FCRA changes that allowed political parties to receive foreign donations—with few or no checks and no transparency.

Amendments: Either Vague Or Minutely Specific

One of the key September 2021 amendments to the FCRA was the prohibition on transfer of foreign contributions, which meant foreign funders could no longer provide one large grant to an Indian organisation that would further distribute these funds to other smaller and more local charities.

The amendment also lowered the limit on the use of foreign donations for administrative expenses, from 50% to 20%, affecting how larger organisations function. However, the term “administrative expenses” was not defined in the Act.

Another significant change was that NGOs had to open and receive foreign funds only in an FCRA account with the State Bank of India’s Parliament Street branch in New Delhi.

A 2019 report by the Centre for Social Impact and Philanthropy (CSIP) of Ashoka University, found that 93% of NGOs with an FCRA licence were registered outside Delhi, a city where they must now have a bank account.

The amended Act also required, as identification documents, details from the national identification database, Aadhar, of all office bearers of organisations seeking FCRA approval.

Inviting room for subjective decision-making, the newly amended law gave greater power to officials to restrict usage of un-utilised foreign contributions, if they had “reason to believe” an NGO had violated the law.

Another amendment allowed the government to suspend an organisation’s registration for 180 days more than the 180 days already provided for in the FCRA, while officials determined if the registration should be cancelled “in the public interest” or if the registration holder had violated the law.

In 2020, the International Commission of Jurists, a group of 60 eminent jurists—including senior judges, attorneys and academics–urged the President of India not to give assent to the amended FCRA, citing its incompatibility with international law, but that did not work.

The Commission also noted that “restrictions in the Bill continued a larger pattern of threats and harassment faced by civil society in India”.

A Time When India Needs NGOs

The government’s decision to suspend the FCRA licences of thousands of NGOs comes at a time of economic distress and a pandemic.

Critics contend (here, here and here) that the government’s refusal to renew licenses is aimed at stifling dissent and suppressing organisations whose work or officials are not considered supportive of either the union government or the ideology of Modi’s Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP).

The onerous requirements of the FCRA not only hinder India’s Covid response, as evidenced during the first and second wave of the pandemic, but there is also growing apprehension (here and here) that the government is using the law as a weapon to attack religious minorities.

As FCRA licenses were cancelled, important humanitarian efforts were halted, even as the constitutionality of the amended provisions was challenged before the Supreme Court in a plea filed by Neol Harper and Nigel Mills of the NGO Care and Share India and Sister Lissy Joseph and Annamma Joachim of the National Workers Welfare Trust in September 2021.

Government Contradictions, Timing & Intent

The “Statement of Objects and Reasons” appended to the Amendment Bill, 2020 claimed the government intended to strengthen compliance, enhance transparency and allow “genuine” NGOs working for the “welfare of the society”.

The government claimed the amendments would enhance “transparency and accountability in the receipt and utilisation of foreign contribution”, but the effect and methods used are the opposite with regards to civil society organisations—quite a different yardstick from the opacity it has allowed political parties, the biggest beneficiary of which has been the BJP.

In 2019-2020, the BJP received Rs 2,643 crore from unknown sources, 3.5 times more than the aggregate income declared by six other national parties and comprising 78.24% of the total income of seven national parties.

Amendments brought by the finance bills of 2016 and 2018 and subsequent events made clear these contradictions, expanded in this timeline:

2014: The Delhi High Court in a public interest litigation (PIL) found the BJP and the Indian National Congress (INC) guilty of having taken donations from “foreign sources” in violation of the FCRA, 1976. The court had directed the union government and the Election Commission of India to act against the political parties. Both parties filed special leave petitions (SLPs) before the Supreme Court, challenging (here and here) the decision of the Delhi High Court in 2014. Till date, no action has been taken against the parties.

2016: On 29 February 2016, the Finance Bill 2016 was introduced and an amendment to the definition of the term “foreign source” in the FCRA 2010, was proposed via clause 233. The intent was that the revised definition would render legal the foreign donations received by the BJP and the Congress, for which they were previously held guilty by the Delhi High Court. On 14 May 2016, the Finance Bill received presidential assent and became law.

When the SLPs filed by both parties were being heard by the Supreme Court, the BJP and INC claimed that the case had become “infructuous” because the FCRA had been amended.

However, the amendment to the definition of “foreign source” was made to FCRA 2010, and not to FCRA 1976, under which both political parties were held guilty. Both the SLPs were withdrawn.

2017: In March 2017, the Association for Democratic Reforms, an advocacy group, and retired bureaucrat E A S Sarma filed contempt of court proceedings against the union of India for failing to act against the political parties, as the Delhi High Court had ordered.

2018: On 1 February, the Finance Bill of 2018 was introduced, through which the government sought to amend the FCRA, 1976. Clause 217, ensconced on the last page of the Bill, read: “217. In the Finance Act, 2016, in section 236, in the opening paragraph, for the words, figures and letters ‘the 26th September, 2010’, the words, figures and letters ‘the 5th August, 1976’ shall be substituted.”

On 29 March 29 2018, the Finance Bill 2018 received presidential assent and became law.

In effect, the government retrospectively amended a dead law, which had ceased to exist on 26 September 2010, when the FCRA 2010 had come into force. A move regarded as illegal, even impossible, was pushed through to evade accountability for violating the law.

“The proposed amendment of FCRA 1976 is akin to trying to conduct a heart or liver transplant on a person who has been dead for seven years,” Jagdeep S Chhokar, former professor, dean and director-in-charge of the Indian Institute of Management, Ahmedabad wrote in The Wire.

Govt Refuses Information On Amendments, Citing ‘National Security’

As the government went to great lengths, including amending a non-existent law, to evade accountability owed by political parties, it has simultaneously fixed all manner of accountability on civil society and nonprofit organisations delivering critical humanitarian work during the pandemic.

At the time of the passing of the 2020 Amendment Bill, when COVID-19 was peaking, as it is now again, many leading NGOs questioned the timing and intent of the government in changing the foreign-donations law.

NGOs argued that the stricter compliance and restrictions imposed would hinder and restrict impact pandemic-related relief. Many found themselves unable to legally accept donations or provide support to grassroots organisations that could reach the most vulnerable, debilitating the national response to Covid-19.

The amendments have proved particularly burdensome to smaller organisations with scant resources. Prominent international NGOs—such as Amnesty International and Greenpeace India—that criticised the government have been driven out of the country, while the government has diverted charitable contributions into the PM CARES relief fund, which remains largely unaccountable and exempt from the provisions of the FCRA.

The government has ignored a concerted effort (here and here) by civil society to have the FCRA amendments suspended, at least for the duration of the pandemic. It has not explained why these amendments occurred at a time of national crisis.

In 2021, when Venkatesh Nayak, a transparency advocate, filed two right to information (RTI) applications asking the ministry of home affairs to disclose the cabinet notes and file notings relating to the amendments to the FCRA Act, both the central public information officer and the first appellate authority rejected the plea on grounds of “national security”.

The ministry refused to provide this information even as it claimed exemption in lieu of “fiduciary relationship with multiple stakeholders” and stated that “disclosure of the same is not likely to serve larger public interest”.

‘Money Has Come To Fund Naxal Activities’

After the 2020 amendments came into effect, a batch of petitions was filed before the Supreme Court challenging the constitutionality of sections 7, 12A, 12(1A) and 17 of the FCRA 2010.

Contending that the amended provisions were violative of Articles 14, 19 and 21 of the Constitution, the petitions argued that the amendments imposed “blanket”, “disproportionate” and “harsh restrictions” on the use of foreign funds by NGOs.

In response, the union government, in a 90-page affidavit, claimed that “there exists no fundamental right to receive unbridled foreign contributions without any regulation”.

“There is no question of fundamental rights being violated through controls of acceptance of foreign contributions by certain types of organisations as the said organisations or individuals are always open to operate with locally secured funds and achieve their expectations”, argued the government affidavit.

On the petitions’ contention that the amendments imposed a blanket ban on transfer of foreign funds to other organisations, a bench of Justices A M Khanwilkar, Dinesh Maheshwari and C T Ravikumar questioned the Centre’s decision to outrightly bar transfer of funds.

"The object of NGOs is to also fund the subsidiary NGOs, why is it prohibited?", the bench asked. Additional solicitor general Sanjay Jain, argued that transfer of foreign funds would be “subject to public policy and it will not be permitted”; and the provision was required to ensure that NGOs did not act as “commission-seeking middlemen”.

On 28 October 2021, the Supreme Court criticised the government: "You are discouraging NGO activities in this process. The result is this.” In November, 2021, the court reserved its judgment. A verdict on the constitutionality of the amended FCRA provisions is pending.

Justice Khanwilkar also asked why the ministry of home affairs was designated as the nodal ministry to monitor FCRA instead of the finance ministry.

“There is an element of national security, integrity of the nation involved here,” said solicitor general Tushar Mehta. “Why should someone sitting in some foreign country pay... Every transaction is watched by the MHA, from the very beginning… Money has come to fund naxal activities.”

The petitioners said that NGOs were unfortunately being viewed through the “coloured lens” of terrorism, and that the amendments were premised on the assumption that organisations receiving foreign funding funded criminal activity.

That is a view the BJP under Modi has indeed held.

The BJP And Modi’s Track Record Of Suspicion

In 2014, as soon as the BJP formed a national government, the NGO sector came under intense scrutiny.

On 3 June 2014, seven days after Modi became Prime Minister, the Intelligence Bureau (IB) submitted a “secret” 21-page report to his office accusing several NGOs of "serving as tools for foreign policy interests of western governments” and “stalling development projects”.

In 2015, the government prepared a list of NGOs, based on inputs from the IB, involved in a range of supposedly inimical activities, such as links with left-wing extremists, “conversion” of tribals to Christianity, and association with sectarian organisations, such as Students Islamic Movement of India.

In 2016, Prime Minister Modi alleged that he was a “victim” of a “conspiracy” by NGOs.

“They conspire from morning to night on ‘how do we finish Modi, how do we remove his government, how do we embarrass Modi?’” he said. “But my friends, you have voted me to rid the country of these diseases.”

Non-profits involved with protests against or critical of the government's policies are now seen as being against the national interest.

According to Rule 3(vi) of the FCRA Rules, 2011, an organisation which habitually engages itself in or employs common methods of political action like 'bandh' or 'hartal', 'rasta roko', 'rail roko' or 'jail bharo' in support of public causes can be declared as an organisation of political nature, and can thus be barred from receiving foreign contributions.

In March 2020, the Supreme Court in Indian Social Action Forum (INSAF) vs. Union of India, read down Rule 3(vi) of the FCRA Rules 2011, and held that the expression of dissent could not be a reason to curb the legitimate right of any organisation from receiving foreign funds.

Weaponsing The FCRA, Particularly Against Christian NGOs

Among the non-profits that no longer have FCRA licences are prominent Hindu organisations, such as the Tirumala Tirupati Devasthanam, the Ramakrishna Mission, and Shirdi’s Shri Saibaba Sansthan Trust.

However, several NGOs have argued the government has particularly weaponized the FCRA against minorities, in particular Christian and Muslim organisations, using the pretext of “religious conversion”.

At a time when religious freedom in India is regarded as being under threat, the government’s refusal to renew the FCRA license of Mother Teresa’s Missionaries of Charity (MoC), on Christmas day, was widely criticised, the first time in 71 years that this had happened to the MoC, which has addressed the needs of millions of destitute Indians.

Father Dominic Gomes, the Vicar General of the Archdiocese of Calcutta criticised the government’s decision a “cruel Christmas gift to the poorest of the poor”.

The government cited “adverse inputs” for revoking the charity’s FCRA status, without disclosing what those were. As the issue gained international attention and was debated in England's parliament, the government reversed its decision on 7 January 2022.

A search of the FCRA website revealed more than 460 cancellations from 2011-2021 of groups with the word “church” in their name alone. According to a report by The CSR Universe, an information platform for Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) initiatives, 70% of the religious NGOs whose FCRA registrations were “deemed to have ceased” were directly or indirectly related to Christianity.

The chairman of New Delhi's All India Islamic Cultural Centre, Sirajuddin Qureshi, told the Economic Times that it was for the “first time in 40 years that the institute has faced a rejection of FCRA over an undefined "procedural lapse".

“They generally give us a warning,” said Qureshi, of his centre, which organises cultural and social programmes. “We sit down with our forms again and see what went wrong." This time, there was no warning.

These concerns have emerged after Bloomberg reported in 2020 how government auditors were questioning executives and accountants of NGOs about the political allegiances of their staff, their Muslim employees and beneficiaries.

NGOs across the board, including religious, educational and cultural organisations and irrespective of their political leanings, have expressed concern over Centre’s move to cancel their FCRA licenses. These issues are made worse by the fact that the government pays scant attention to procedural hurdles that it throws up.

Government’s Failure To Address Technical Difficulties

As many as 12,989 NGOs applied for renewal of their registration between 30 September 2020 and 31 December 2021, the Indian Express reported in January 2022.

The FCRA registrations of 5,789 NGOs were “deemed to have ceased” because they did not apply for renewal before the due date of 31 December, and nearly 170 organisations that did, were refused, as the home Ministry found their operations to be in violation of the FCRA.

It appeared that most organisations lost their FCRA status on account of technical or administrative reasons, such as failing to submit paperwork in time.

Digital returns and onerous compliance requirements present significant challenges, particularly for smaller organisations that lack the capacity. This ties into the change in filing requirements from an older Form FC6 to a more detailed and onerous Form FC4.

In July 2021, the Delhi High Court "restrained" the government from taking any "coercive" action against NGOs that failed to file their annual returns before 30 June 2021.

Many NGOs had expressed their inability to submit their annual returns under Form FC-4 for the year 2019-2020, as the online system, introduced through the 2020 amendments, accepted entries only if the account was at the SBI's Parliament Street branch at New Delhi.

However, a Supreme Court decision on 25 January 2022 came as another blow to NGOs, as the judges declined a plea filed on behalf of nearly 6,000 NGOs, seeking continuation of their FCRA licenses, and directed them to make a representation to the union government.

In 2017, the central government mandated a unique identification number called the DARPAN ID, but, after the decision was criticised, it was made optional. NGOs that fail to procure the unique identification number through the DARPAN portal, however, face restrictions.

For instance, an 8 April 2021 order of the ministry of women and child development stated that “no financial grant from central government will be disbursed to any NGO/VO without obtaining the unique ID generated from NGO DARPAN Portal of Niti Ayog”.

The stringent compliance requirements made many organisations, such as Oxfam India, Medical Council of India, Commonwealth Human Rights Initiative, Emmanuel Hospital Association, and the Indian Medical Association, which assist Indians and communities in need and have a long-standing reputation, ineligible for foreign funding.

Some of the prominent educational organisations on the no-foreign-funding list were the Delhi College of Engineering, Jamia Millia Islamia, DAV College Trust and Management Society, Nuclear Science Centre in JNU, and Lady Shri Ram College for Women.

The ministry of external affairs’ think tank, the India Centre for Migration (ICM), which advises the ministry on matters relating to international migration and mobility, too, lost its FCRA license, revoked even though a government official confirmed that they told the home ministry that they had shifted their account from Canara Bank to the designated SBI branch in Delhi.

As with every other case, there was no explanation why this had happened.

(Mani Chander is a lawyer based in New Delhi.)