New Delhi: “It feels like it happened only yesterday,” the frail 55-year-old woman said. Wearing a tracksuit that hung loosely on her shrunken frame, she shifted restlessly, fidgeting constantly. Her five-year-old granddaughter quietly coloured a giant undersea fantasy of mermaids.

Both were witnesses to a gangrape, the viral video of which came to symbolise the brutality of ethnic cleansing and bloodletting in Manipur in 2023: more than 260 dead, 386 religious institutions of both communities damaged in the first month of the conflict, more than 60,000 people still internally displaced.

As the conflict deepened and the state and union governments remained unable to stem the tide of violence, the state was divided into ethnic enclaves—of majority Meitei, largely Hindu, and Kuki-Zo, the majority Christian—with no resolution in sight.

“My girl (her granddaughter) remembers everything,” said the grandmother, whose account revealed police involvement in the gangrape. “Ask her how we escaped, and she’ll tell you every detail.”

After nearly a year of President’s Rule, Manipur has a popular government, with Y. Khemchand Singh as chief minister and Nemcha Kipgen, one of the state’s 10 Kuki MLAs, as its first woman deputy chief minister. Along with her, Naga People’s Front legislator L. Dikho also took oath as deputy chief minister of Manipur.

Three BJP kuki MLAs who had earlier demanded a separate administration have participated in the formation of the popular government. These include Ngursanglur Sanate, the BJP MLA from Tipaimukh constituency, and Churachandpur MLA L. M. Khaute.

“Was our suffering not enough? How can they form a government with the Meiteis? None of these MLAs came to meet us or ask about our well being,” she said.

“She is a woman too, how could she not understand our pain?” she added, referring to Kipgen.

“I can never go back. The only reason I would return to my village is to see my daughter’s grave.”

One of her three daughters passed away in 2020 due to illness.

According to a chargesheet filed by the Central Bureau of Investigation (CBI) against six men in the case about the assault and gangrape on 4 May 2023 near B Phainom village in northern Manipur’s Kangpokpi district, three women had sought the help of police personnel present at the scene of violence but were left at the mob's mercy.

The women, one of whom is the wife of a Kargil war veteran, pleaded with the police personnel to drive them to a safe location. They were instead driven in a police vehicle right to the mob, after which police refused to go any further, the chargesheet said.

The two women who were with the eyewitness in the police vehicle that day were gangraped and paraded naked. The eyewitness, who was also beaten and punched by the mob, said she has no home to return to—her village home was destroyed in the violence along with her faith in the law and order machinery of her home state.

The family now lives in exile, 2,000 km to the west, in a two-room apartment in Delhi, struggling to make ends meet. Her daughter, 29, is a saleswoman at a store, supporting the family on her Rs 40,000 salary. With Rs 17,000 going to rent, getting by is difficult. Even in the peak of a Delhi summer, all they had to cool the flat was a table-fan.

On 10 January 2026, a young Kuki-Zo woman who was gangraped during another wave of violence in May 2023 in Imphal, died in Churachandpur. Her death, on account of health complications from the assault, refreshed traumatic memories for the eyewitness and her family.

On 4 May 2023, the day of the assault, the grandmother we spoke to ran miles with her granddaughter strapped to her back with a cloth. A first information report (FIR) was filed on 21 July 2023, 67 days after the gangrape. In 2024, she was named a key eyewitness in the CBI’s chargesheet.

As she spoke to Article 14, the grandmother kept folding and unfolding her legs, rubbing her feet as if to soothe a pain that refused to leave.

“She (the granddaughter) prays to God often for them (the culprits) to be sent to hell,” said the woman. “She says that they took away her toys and her cycle. She also recalls how they burnt down her home.”

It was the viral video that finally led Prime Minister Narendra Modi to break his silence on the ethnic conflict in Manipur. He visited the state in September 2025, for the first time since the violence erupted more than two years earlier.

During his visit, the prime minister travelled to Churachandpur, the major Kuki-Zo city, and Meitei-dominated Imphal, the areas most affected by the conflict. Modi appealed for peace and reconciliation but for survivors of the violence, normalcy is distant, shadowed as it is by a deep rupture of trust.

“What did he (Modi) even come here now?” the grandmother said. “He’s not going to give us a separate administration. After all this, how does he expect us to live together again? The trust is gone.”

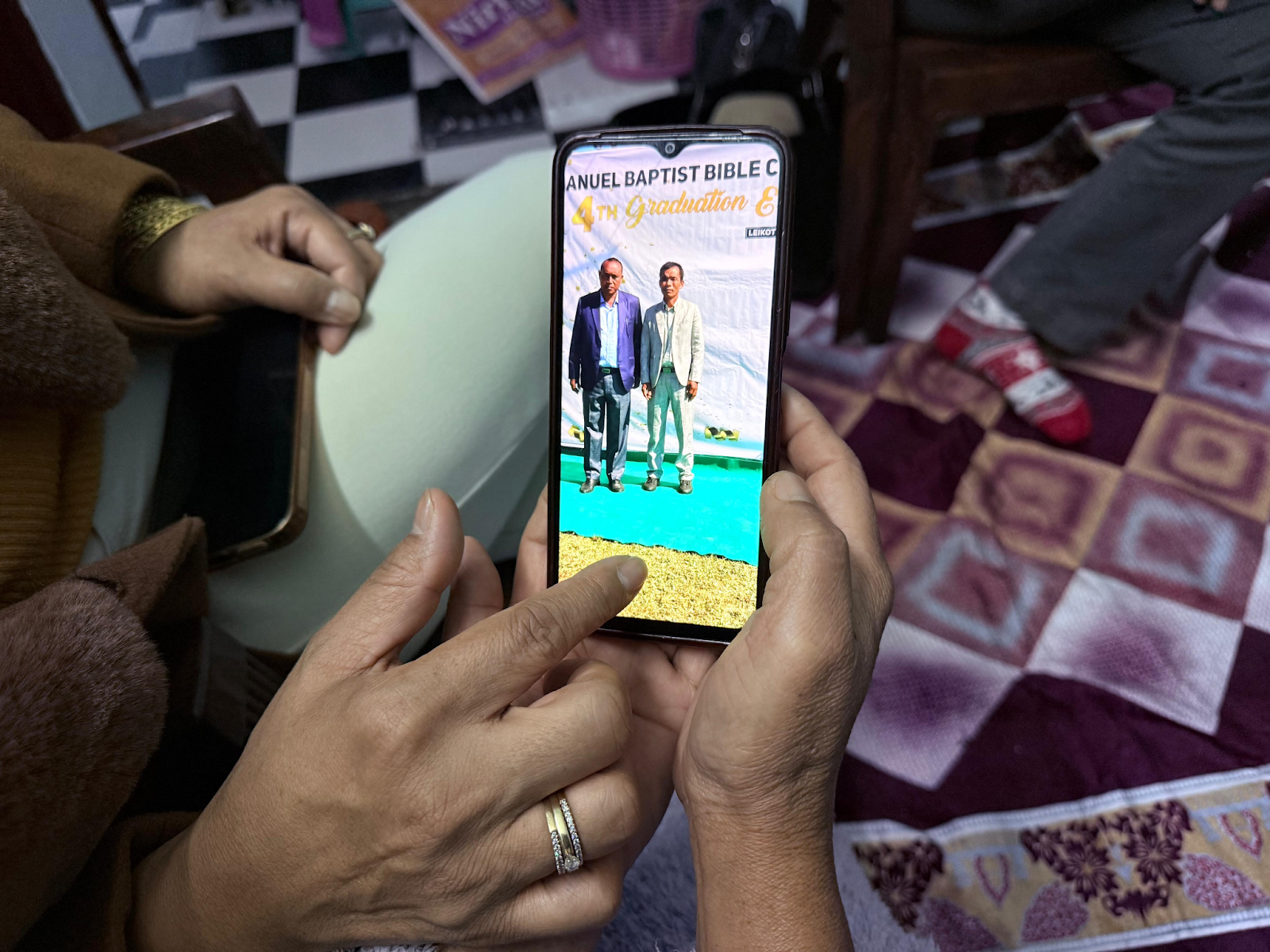

Her husband, a farmer back in Manipur, has been unable to work in Delhi. Suffering from a stomach ulcer and other health niggles, he has found language to be a significant barrier to finding work in Delhi. The family speaks Vaiphei, a Sino-Tibetan language spoken primarily by the Vaiphei sub-tribe of the Kuki Zo tribal people in Manipur.

After 2 Years, Trial To Begin

On 2 January 2026, a special CBI court in Guwahati framed charges against six men, formally setting the case down for trial. The charges include murder, gang rape, forcible stripping, arson, promoting communal enmity, and multiple offences under the SC/ST (Prevention of Atrocities) Act.

The development follows an interim Supreme Court order of 25 August 2023, which transferred all CBI-probed cases linked to the Manipur violence, including the viral video case, from Manipur to a special court in Guwahati, Assam.

Charges were framed in the court of special judge Chatra Bhukhan Gogoi after hearing arguments from both sides and examining the charge sheet, witness statements, video evidence, and government sanction. Article 14 has seen a copy of the order framing the charges.

Charges were framed against the accused, namely Huirem Herodash Meitei, Arun Khundongbam, Ningombam Tomba Singh, Yumlembam Jiban Singh, Pukhrihongbam Suranjoy Meitei and Nameirakpam Kiran Meitei, who have been charged as members of an unlawful mob that acted with a common purpose during the violence.

Four of the accused are currently in judicial custody, while two are out on bail. Rejecting a bail plea filed by prime accused Ningombam Tomba, the CBI court said on 28 January 2026, the CBI court called the offence “most heinous, inhuman and barbaric in nature”

The case is based on a complaint filed on 18 May 2023 at Saikul police station, by the chief of B Phainom village.

According to the complaint, a mob of 900–1,000 armed men stormed the village on 4 May 2023, burning homes and a church, looting property and livestock, killing villagers, and sexually assaulting women.

“They looted homes, set them ablaze, killed villagers, and sexually assaulted women,” the complaint stated. An FIR was registered the same day against “unknown miscreants numbering about 900–1000 persons”.

The eyewitness Article 14 spoke to was among a group of 10 villagers who fled into the Haokhongching forest as their village burned.

“We ran in different directions when the mob spotted us,” she recalled.

One group of rioters dragged away two men and the two women who were later seen in the viral video; another group of rioters took away the village chief, her husband and their two daughters; while a third group cornered her as she carried her infant granddaughter on her back.

She remembered how her two daughters pushed their father, 68, out of the mob’s path, shielding him with their bodies. “That’s how he survived,” she said. “They became witnesses to everything that happened.”

As men from nearby villages joined the mob, some victims were told to move towards a police Gypsy parked by the roadside.

According to the CBI chargesheet filed in October 2023, and the survivor’s account, the two women who were later gangraped and a male relative managed to get inside the vehicle and begged the policemen to take them to safety.

The chargesheet says the police personnel drove the Gypsy towards the mob and abandoned it, leaving the victims exposed. The mob then dragged the two women into a nearby paddy field, where they were stripped, paraded naked, and gang-raped.

The father and younger brother of one of the gangrape survivors were beaten to death, and their bodies were later dumped in a dry riverbed.

“They were just trying to protect them,” the eyewitness said.

The CBI charged six accused with murder under section 302, unlawful assembly under section 149 and 15 other sections of the Indian Penal Code, with a record that Arun Khundongbam played an active role in the killings.

The eyewitness said she was nearly stripped as well, but escaped when the attackers turned their attention to the other two women.

“I was holding my granddaughter tightly,” she said. “Maybe that’s why they left me. Otherwise, I would have been like them. She saved me in a way.”

She pleaded with the policemen to help her husband, but they ignored her. When she tried to climb into their vehicle, she was “pushed away”, the chargesheet says. She survived only because the mob tormenting her shifted its focus to the group assaulting the two other women and killing their male relatives.

She fled deeper into the forest with her granddaughter and hid through the night. Weak with hunger, the child cried all the way.

“I thought we were going to die anyway,” she said. At dawn, she stepped into a nearby village in search of food or water. “I walked into the first house I saw. No one was in the house, so I gave her whatever I could find to eat,” she said. The two were reunited with their family the next day in a Naga village.

The court framed charges for seven sexual offences, recording that the tribal women were forcibly stripped, prevented from wearing clothes again, threatened and paraded naked in public, and that two of them were gang-raped in broad daylight during the communal violence.

The accused were charged under sections 354 (assault or use of criminal force to outrage a woman’s modesty) 354 B (criminal force with intent to disrobe), 376(2)(g) and 376 D (gang rape), 153 A (promoting enmity between communities) and 436 (arson) of the IPC.

Noting that the accused belong to the Meitei community and the victims to a scheduled tribe community, and that the attacks were carried out with this knowledge, additional charges were framed under the SC/ST (Prevention of Atrocities) Act, 1989.

Then And Now

A narrow, airless alley in a South Delhi neighbourhood led to the eyewitness’s two-room rented apartment. The doorway was missing a proper door, just a faded curtain swaying in its place. Seven family members live together in the cramped space.

Her daughter-in-law is the family’s sole breadwinner, working as a salesperson at a store in Delhi.

The others drift in and out of jobs. The eyewitness said her daughters, still deeply shaken by the violence, are unable to hold down work and often fall ill.

As she spoke, she gestured toward one of them, lying curled up on the floor in the other room.

Her granddaughter stood by the small Christmas tree in the corner of the room, repeatedly taking down the decorations and carefully putting them back.

“We want her to forget everything and feel that all is well,” she said. “The Christmas tree, though expensive, was an attempt to bring her some happiness and normalcy.”

The room itself told a harsher story. The flat has no windows except for a small one in the kitchen. The window was open for ventilation, but there was no heater to shield them from the extreme winter chill.

“It has been very challenging for us since then. We don’t have a home here,” she said, tears welling in her eyes. “I feel like a beggar.”

In her village in Imphal, she recalled, life was secure. The family owned land, grew enough rice to last the year, and stored surplus harvest in a granary. They raised animals, chickens they could slaughter for meat, pigs they could sell for cash.

“We were self-sufficient,” she said softly. “We had a garden, a new kitchen, everything we needed. We were happy, healthy, and strong. Now… It's all stress. Our minds don’t work any more.”

The physical toll of the assault, her subsequent escape and life in exile has left her with a limp. Climbing the three flights of stairs to their flat takes her more than ten minutes.

Her husband, watching her from a corner, broke down as she spoke. She had always been the strongest in the family, he said, the pillar of their household, someone who could carry logs of wood from the fields without pausing.

“Now look at her,” he murmured. “So weak… dragging herself. The zeal she had for life is gone.”

Cycle Of Trauma Continues

Back in Churachandpur, the two victims from the viral video have withdrawn from the world. They rarely step outside or speak to anyone, not even their families. The memory of the night they were assaulted still haunts them, and the fear that the video might resurface never leaves.

One of them, who was 21 at the time of the assault, has largely confined herself to her home and often, just her room.

“She doesn’t talk to anyone, not even her mother,” said a member of the Vaiphei Zillai Pawl, a student organisation of the minority Kuki-Zo community in Churachandpur district that has been supporting the two women since the incident. “Sometimes she even stops eating for days.”

The organisation continues to help the women in practical ways, including accompanying them to attend online court hearings related to their case. The member stated that the younger survivor wishes to continue her education, and they are currently seeking funds to support her. “We want to rehabilitate them properly,” the member said.

Both women now live in rented houses. The trauma lingers, partly because the video never fully disappeared from social media.

“It resurfaces sometimes. They have phones and they come across the video,” said the member. “The 51-year-old survivor is always terrified of that possibility.”

“Whenever it reappears, everything collapses. They go through the entire cycle of trauma all over again, and all the progress they’ve made just falls apart.”

The member said they had also requested the district administration to allow the women to meet the Prime Minister during his visit to Manipur.

“It was this video that compelled him to speak about the Manipur violence for the first time, yet he didn’t meet the victims,” said the member. “Our request was turned down by the district officials.”

However, when Article 14 spoke to district officials, they said no such request was made.

The member confirmed that both survivors received financial assistance from the government, though they did not specify the amount. The eyewitness in Delhi said she received Rs 12 lakh as compensation.

The National Human Rights Commission on 17 November 2023 directed the Manipur government to provide compensation of Rs 10 lakh within six weeks to the next of kin of all the people who died in ethnic clashes since May.

The Supreme court in 2023 also appointed the three-member Justice Gita Mittal committee to oversee compensation for victims under section 357A of the Criminal Procedure Code (payment of compensation), the National Legal Services Authority (NALSA) Compensation Scheme for Women Victims/Survivors of Sexual Assault (2018), and the Manipur Victim Compensation Scheme (2019), and to ensure timely disbursal of funds through the Manipur State Legal Services Authority.

NALSA received 118 applications for compensation from Manipur between April 2024 and March 2025. Of these, 98 applications were approved, and Rs 2.26 crore was sanctioned.

‘We Are Alive But Forgotten’

Without leaders willing to speak up for them, the eyewitness living in South Delhi said she does not want to return to Manipur.

“We are alive, but forgotten. Nobody feels the pain the way we do,” said the grandmother, adding that the community continued to live in fear and had no faith that they wouldn't be attacked once again if they returned. “As miserable as life is here, I can’t return,” she said. “I fear for the lives of my family.”

A global report on internal displacement by the Geneva-based thinktank Internal Displacement Monitoring Centre called Manipur’s displacements the highest number of conflict-related displacements recorded in India since 2018, accounting for 97% of all displacements caused by conflict and violence in South Asia in 2023.

“I still wake up in the middle of the night with sudden anxiety and breathlessness,” she said, looking at her granddaughter. “This little one was never supposed to see this… no child was.”

(Mrinalini Dhyani is a journalist based in Delhi. She writes on gender, governance and conflict.)