New Delhi: In September 2024, Rajasthani officials told India's national environmental court that there was no illegal mining or stone quarrying in the bed of the Sota, a tributary of the Sahibi river, which rises in north-eastern Rajasthan and flows through parts of southern Haryana.

Acting on a petition filed by two Rajasthani activists in April 2024 alleging illegal mining and stone crushing in the Sota riverbed in the district of Kotputli-Behror, the National Green Tribunal (NGT) ordered an investigation.

At a September hearing, the sub-divisional officers (SDOs) of Kotputli and Behror tehsils and the deputy conservator of forests (DCF) for Kotputli-Behror denied allegations of illegal mining. Also present at the hearing were the SDO of Paota, another tehsil in Kotputli-Behror district and an executive engineer of the state’s water resource department (WRD).

The Sota river originates in Paota before running through Kotputli and Behror. For almost a decade, local residents and activists have protested against stone quarrying in the Sota.

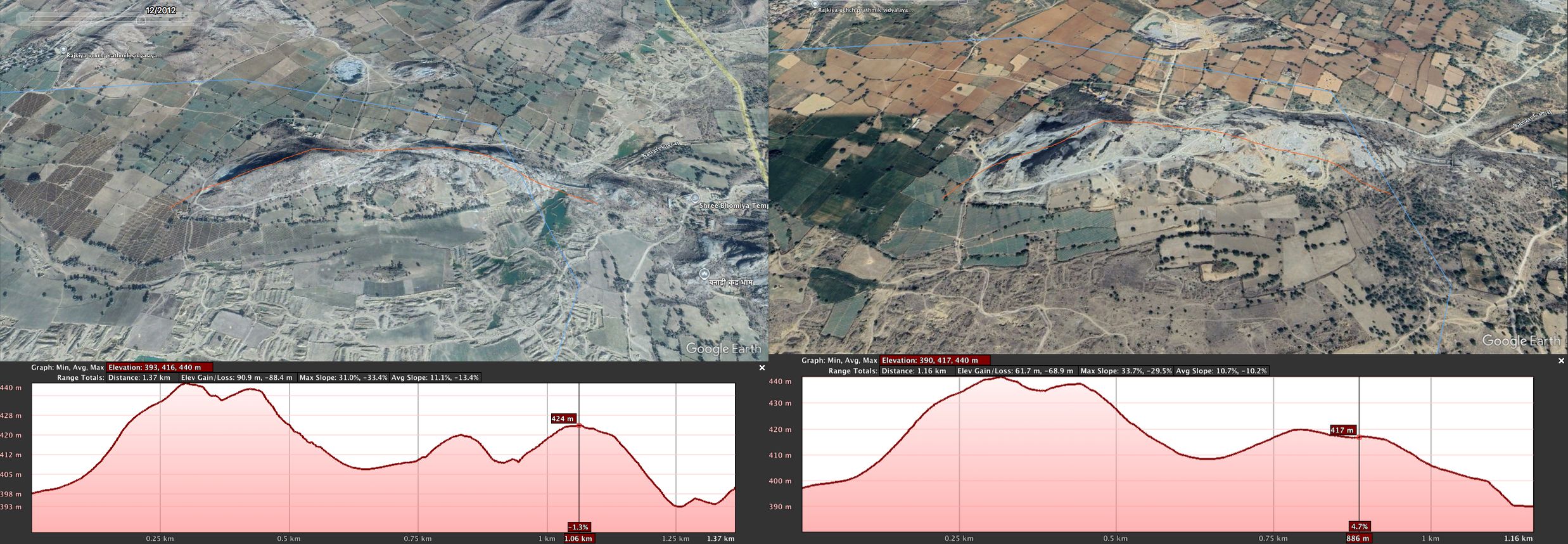

However, satellite imagery accessed by Land Conflict Watch shows widespread destruction of the Sota river over the years, traces of acute land degradation, and flattened hills, caused by sand mining and stone blasting.

Article 14 spoke to residents of villages around the Sota who said long stretches of the river had become a hotbed for illegal mining over several years.

Government officials from the water resources and the mining departments too provided evidence of illegal mining in the region.

In a country where ecosystems and millions of people depend on rivers for survival, the Sota's destruction—by violating India's environmental laws and official collusion—is a warning of similar destruction and denial.

The Sota's story illustrates growing pressures to exploit natural resources, in this case for India’s booming construction industry, a leading source of jobs and—for those running such businesses—fortunes.

The SDOs and DCF of Kotputli and Behror did not respond to questions from Article 14, while Sonu Awasthi, of the Kotputli mining department and a member of a committee constituted by the NGT to probe the allegations, refused to answer any questions.

A Satellite Fact-Checks Claims

The satellite images that we accessed, based on GPS coordinates provided by the WRD in its report to the NGT on 5 September 2024, revealed the extent of environmental damage in a region that is home to endangered flora and fauna, including medicinal plants.

Located nearby is the Baleshwar conservation reserve, which houses critical wildlife, including panther, leopard and fox.

The GPS coordinates provided by WRD were of the main illegal mining points in the flow and catchment area of the Sota river, as site visits by an NGT-constituted joint committee noted.

“There have been obstructions in the flow area of the Sota river due to illegal mining… with the help of administration, illegal stone crushers (without appropriate land conversion orders) have been removed from the flow areas of Banedi Dam,” the status report said.

Land Conflict Watch mapped the GPS coordinates and found that the flow of the Sota river has drastically reduced over the years.

There are signs of soil erosion and a notable flattening of hills, substantiating testimonies given to the NGT by WRD officials, the assistant mining engineer, and the SDO of Paota tehsil, who all conceded that they had observed illegal mining and stone crushing operations in the affected area.

Anti-mining activist Kailash Meena told Article 14 that illegal mining and stone crushing don’t just refer to those activities that are being continued despite the absence of leases but even those operations that occur on unsustainable levels. An acute habitat loss is visible in the district, he said.

‘Alarming Condition’

Acknowledging the petitioners’ plea of the near-complete disappearance of the Sota, the NGT, in its latest hearing on 3 October, noted the “alarming condition” of the river and ordered the district magistrate of Kotputli-Behror to prepare an action plan for its restoration.

In 2017, the Supreme Court (SC) banned sand mining in Rajasthan's riverbeds, requiring a scientific replenishment study and clearances from the union ministry of environment, forests and climate change (MoEFCC) before mining could resume.

It later appointed a central empowered committee (CEC) to look into the issue of illegal sand mining in the state.

In 2021, accepting the CEC’s recommendations, the SC lifted the blanket ban, accepting the argument that the four-year-old ban had inadvertently spurred illegal mining activities and conflicts between locals and mining mafias.

Mining in riverbeds and riparian areas is usually for the extraction of sand, boulders and gravel, all used in the construction industry, a sector that contributes nearly 8% of India’s GDP.

As the construction sector grows, the demand for sand and gravel as aggregate for construction of highways, bridges, buildings, etc is pegged to rise sharply, while their sources—floodplains of rivers, in-stream areas of riverbeds, beaches—witness increasingly intensive exploitation of this resource.

Across India, illegal and unregulated riverbed mining has induced changes in river morphology, riverbank erosion and water pollution, posing hazards to local communities (see here, here, here, here and here).

In the desert state of Rajasthan, where surface water resources account for only about 1% of India's surface water resources, any damage to riverbeds or change in river flow patterns is a grave crisis for ecosystems depending on the river.

Miners routinely fail to map the area covered by their leases, said Neelam Ahluwalia, founder-member of the Aravalli Bachao Citizens Movement, a public movement to save the world’s oldest fold mountains, formed by the collision of tectonic plates, from destruction by mining, real estate, dilution of protective laws and other threats.

This enables them to excavate beyond the permitted boundaries. According to Ahluwalia, miners also routinely set off explosions to blast stones at decibel levels well above the 70db-75db approved by Rajasthan Pollution Control Board.

Ahluwalia, who has been tracking illegal stone blasting in the Kotputli-Behror district, has found even licenced mining operators flouting rules and regulations, and mining activities being carried out closer to villages than permitted—in some cases less than 90 metres from human habitation, instead of the 500 metres-1 kilometre minimum distance mandated.

“The same is evident in how mining operations are conducted so close to water bodies in this and neighbouring districts, despite such activities being prohibited,” she said.

Degradation Of The Sota

The Sota is a perennial river fed by rain, overflow of water from dams and from small tributaries originating from the Buchara forest in the hills. It plays a vital role in replenishing groundwater and sustaining ecosystems along its 250-km length.

According to activists and residents, the river has suffered extensive degradation, including disruption of its natural flow and major damage to its catchment area, over the past two decades.

The flow of the Sota river has almost ended, particularly in the monsoons, wrote Nikita Gupta, a research scholar at the Raj Rishi Bhartrihari Matsya University in Alwar, Rajasthan, in a paper on environment degradation in Alwar.

Gupta argued that the water flow was affected by the “illegal mining of gravel on a large scale in the flow area” that had caused “deep pits and rough surface” on the riverbed.

The petition that led to the NGT investigation was filed by anti-mining activists Amit Kumar and Kailash Meena.

The petition alleged that the Sota river faced an environmental crisis from unauthorised mining and stone crushing operations in its riverbed, unlawful encroachments, and neglected maintenance. It also claimed that explosives were being used illegally for blasting large boulders, endangering the lives of local residents and damaging the environment.

“The illegal mining is degrading the environment of the Sota river and threatening the region's ecological balance, loss of groundwater and contributing to the water scarcity in the region,” read the petition.

Meena, a long-time advocate against illegal mining, told Article 14 that even legitimate mining operations all along the river’s length, licenced by the state government, were flouting several environmental laws including the Environmental Protection Act, 1986; the Forest Conservation Act,1980; the Water (Prevention and Control of Pollution) Act, 1974; and the Air (Prevention and Control of Pollution) Act, 1981.

Ahluwalia said dump trucks at mining sites were often overloaded, worsened air quality and contributed to respiratory issues. Mining operations also cause soil erosion and sedimentation in the water stream, both of these harming aquatic life.

Meanwhile, in a report submitted on 5 September to the Rajasthan Pollution Control Board by the executive engineer of the state’s WRD, officials said illegal mining was the primary contributor to the river’s environmental decline. They said excavation in the river bed had obstructed water flow to reservoirs like the Buchara dam, reducing its inflow capacity dramatically over the years.

Villagers and activists have also complained about silicosis, a debilitating lung disease caused by silica dust, as well as the physical damage to homes and water bodies caused by blasting.

“There is a lot of cement that settles on our terrace,” said Kripa Devi, a resident of Jodhpura village. She said she dreaded the thought of the long-term impact of living so close to a cement plant that extracted its raw materials from quarrying rocks.

“Allergy, asthma, breathing problems and itching have become quite common,” she said. “It is especially difficult for older people,.”

Cases Against Illegal Mining

Though local administration officials of the Kotputli-Behror district denied that any illegal mining was being undertaken in the Sota, the state’s own WRD has, between 2013 and 2021, filed at least six first information reports (FIRs) against illegal mining activities in the river.

Some of these FIRs were filed by Yasveer Singh, an assistant engineer with the WRD.

He told Land Conflict Watch over a phone call that his inspections revealed gravel-washing plants, unauthorised transportation of stone, and blasting activities near dams—an area where mining is prohibited. “Illegal mining has been happening for years, often under the protection of influential individuals,” Singh said.

The assistant mining engineer of Kotputli tehsil told the NGT in a 15 July letter that several cases of illegal mining had been observed between 2010 to 2024, and that the department had taken action against at least 2,113 cases of illegal mining, transportation and storage in the Sota river.

The SDO of Paota tehsil admitted to the NGT that there had been cases of bajri mining—the extraction of riverbed sand. The SDO claimed that regular action was being taken in these cases by the administration along with the WRD and the mining department.

In response to the April 2024 petition, the NGT constituted a joint committee to conduct site inspections and to verify reports of illegal activities on the riverbed. The committee included officials from the Rajasthan Pollution Control Board, the Central Pollution Control Board, the state’s WRD, the ground water department and the tehsildar of Paota.

Satellite Photos: The Smoking Gun

The committee conducted visits to various spots along the Sota on 14 June and 2 July 2024.

Notably, the committee’s observations also noted traces of illegal mining operations and stone crushers at various locations in the affected area.

Satellite imagery of GPS coordinates provided by the WRD, and verified by Land Conflict Watch, revealed compelling evidence of extensive mining and environmental degradation in the region.

These images highlighted scars on the landscape and unauthorised excavation activities, corroborating claims made by activists and WRD officials. The imagery has been a crucial tool for activists, strengthening their fight against local officials’ denials of illegal mining operations.

Despite this evidence, the SDOs’ submissions to the NGT claimed that only 84 encroachments—permanent and temporary housing by villagers—exist on the riverbed. This assertion shifted the focus away from the mining operations flagged by other government entities and activists.

The Big Picture

Illegal sand mining is a widespread issue in Rajasthan, driven by high demand and lucrative profits.

The sand trade in India is valued at over $126 billion annually, employing millions. However, the environmental cost is immense, with water bodies and ecosystems bearing the brunt.

The Kotputli-Behror district, carved out from Alwar and Jaipur districts in 2022, has become a hotspot for illegal mining. Reports indicate that over 3,900 cases of illegal mining were registered in Alwar and Jaipur districts by September 2019. Penalties exceeding Rs 24 crore have been collected, yet enforcement remains inadequate.

Villagers and activists in Kotputli-Behror have long demanded action against illegal mining. Recently, Kotputli district was in the news for a citizens’ dharna (a peaceful demonstration) against a cement company, where they demanded the right to breathe clean air.

While temporary halts have occasionally been ordered, illegal mining inevitably resumes, said residents, leaving them disillusioned with the authorities.

At an October hearing, the NGT noted that the mining, water resource, forest, and land revenue departments were yet to submit relevant information to the committee. The tribunal also ordered the district magistrate of Kotputli-Behror to prepare a time-bound action plan to restore the damaged river.

The tribunal sought a report on the plan before the next hearing.

As the NGT continues its investigation, the spotlight remains on the contrasting narratives—official denials versus irrefutable satellite evidence.

(Sukriti Vats is a Writing Fellow with Land Conflict Watch, an independent network of researchers, which carries out research on land and natural resources.)

Get exclusive access to new databases, expert analyses, weekly newsletters, book excerpts and new ideas on democracy, law and society in India. Subscribe to Article 14.