Delhi: Thousands took to the streets in the main market of Kargil this week, demanding Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s government restore Ladakh’s statehood and include it in the sixth schedule in the Indian Constitution. This would give them autonomy to make laws to preserve their tribal culture, heritage, customs, environment, and way of life.

In the four years and six months since the Modi government rescinded the autonomous status of Jammu and Kashmir, bifurcated it from Ladakh, and turned both into union territories which the centre governs, the two religious minorities in India that live in Ladakh—Buddhists and Muslims—have come together to “fight for democracy”. They want more jobs, political representation and participation in the governance of the region with a population that is 97% tribal, bordering China on one side and Pakistan on the other.

“Ladakh is voiceless right now. We had an Assembly to express our problems, resentment, and sorrows. Today, we are in a vast area but don’t have representatives who can speak for us. Ladakhis will have no role in decisions about our identities, glaciers, and environment,” said Sajjad Kargili, a key figure behind the protest and a member of the six-member subcommittee in talks with home minister Amit Shah.

“So, Buddhists and Muslims have come together to fight for democracy in Ladakh,” he said.

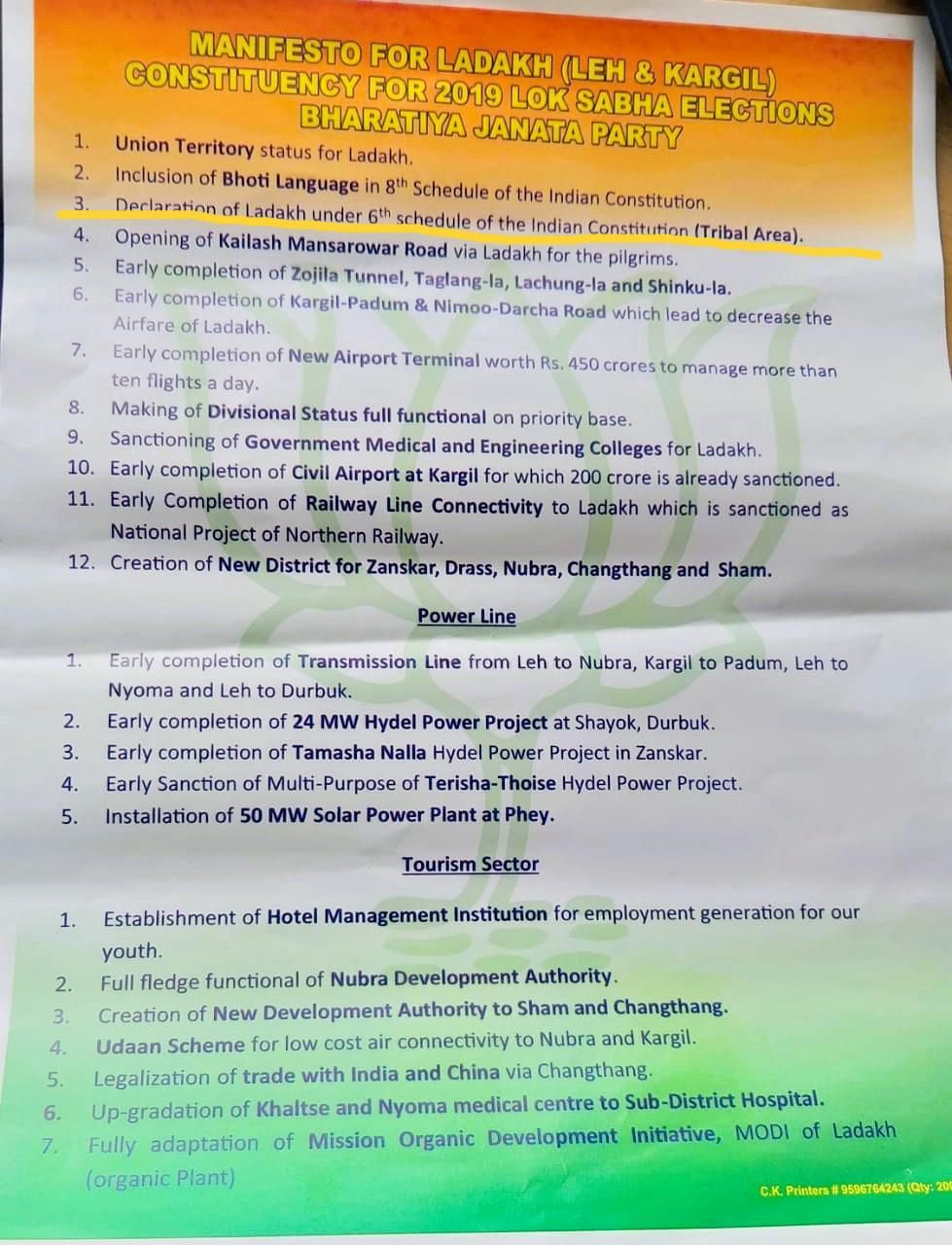

In its manifesto for the Ladakh Constituency, the BJP promised the sixth schedule ahead of the 2019 Lok Sabha election in May.

Before the abrogation on 5 August 2019, Article 370 and Article 35 gave special rights and privileges to citizens of J&K and Ladakh. They stopped outsiders from buying land, getting government jobs, and settling in the erstwhile state, which was India’s only Muslim-majority state. These protections were seen by many as discriminatory, and the ruling Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) had long pledged to get rid of them.

With these protections gone and no more representation in the J&K Assembly (there were four lawmakers before August 2019), the tribal communities have felt more and more left out of the decision-making process and vulnerable to outside elements and corporations that could acquire vast tracts of land and destroy the delicate ecology, environment and way of life.

Ladakh, which used to be 60% of J&K in size, currently has only one representative in Parliament.

Shah has refused the demand for statehood, the sixth schedule, and the legislature but is considering Article 371 to address concerns about jobs and land. In 11 states, some special protections are granted depending on the state's unique circumstances, but autonomy is not granted.

The periodic labour force survey between 2022 and 2023 showed the highest unemployment in Andaman & Nicobar Island, at 33%, followed by Ladakh, at 26.5%, and Andhra Pradesh, at 24%. The Modi government told Parliament that Ladakh registered the sharpest increase in the number of unemployed graduates in India between 2021- 2022 and 2022-2023.

The nine tribes that live in Ladakh are Balti, Beda, Bot, Bropka (Dropka), Dard Shin, Changpa, Garra, Mon and Purigpa. They speak many languages, including Ladakhi, Urdu, Purgi, Brokskat Balti, Purigi, Shina and Zanaskari.

Even the Buddhists in Leh, who initially supported the abrogation and demotion to a union territory, have changed sides.

Sonam Wangchuk, an engineer and climate activist, backed the UT even as he said that the influx of outsiders would destroy the desert ecology of the place. He is now the face of the protest, recently ending his 21-day fast.

In 2020, the Leh Apex Body and the Kargil Democratic Alliance, comprising people from religious bodies, political parties, and trade unions, were formed and have been working together to build a public movement while negotiating with the governments and organising protests.

Famously, in 2022, the two religious communities resolved a 42-year-old dispute about setting up a Buddhist monastery in Kargil town, home to Shia Muslims. The Muslims gave the Buddhists the land for the construction.

The only representative bodies that Ladakhis have are the Ladakh Autonomous Hill Council in Leh, constituted in 1995 and the one in Kargil in 2003. They have 30 members each—26 elected and four nominated. The BJP leads the one in Leh. The National Conference and the Congress Party lead the one in Kargil.

But according to Kargili, also a member of the Kargil Democratic Alliance, the bodies get only six percent of the budget for Ladakh and the bureaucrats in Delhi to ride roughshod over the councillors who are stripped of any real power.

“Our hill councils are disempowered. They are there for show, as no powers have been left for them,” he said.

The model code of conduct is in place. Why have you chosen this time for a protest?

We know the model code of conduct is ongoing, and the government is a take-care government that cannot make a decision. Still, our main aim is to convey to the people of India and the government that talks have failed recently. However, we still demand statehood and a sixth schedule for Ladakh to protect our environment and land, secure jobs, and restore democracy in the region.

How have the talks with the home ministry gone?

We have written down what Ladakhis are demanding, but nothing concrete has emerged. We met them on 23 February and discussed the public service commission issue, the job issue, and the two parliamentary seats for Kargil. On the parliamentary seat issue, they said the delimitation will be held in 2026. There is no point in discussing this issue. We understood that and said we would discuss it later, but let’s discuss the other issues.

Not a single Ladakhi has been recruited in a gazetted post for the last five years in Ladakh. Ladakh is second in the unemployment ranking. The ICMR (Indian Council of Medical Research) said Ladakh is the worst for hypertension—48% are facing hypertension. For the last four years, there has not been any democracy. The government is not taking the local stakeholders into confidence to discuss any policy with them. They are making decisions on their own.

The government agreed to extend the Jammu and Kashmir Public Service Commission to Ladakh, and it also agreed to give 85% reservation to STs in Ladakh for gazetted posts. We have succeeded in the unemployment issue. However, regarding statehood and the sixth schedule, the government does not agree. Amit Shah clearly told us that we can give you neither statehood nor the sixth schedule or a legislature. He also said that he made a mistake by making Ladakh a UT. After that, people were angry. Sonam Wangchuk was on a hunger strike for 21 days, and we, the Kargil Democratic Alliance, were also on hunger for three days. In the coming days, the Leh Apex body and Kargil Democratic Alliance will decide on future actions.

It must have been pretty tense when he said making Ladakh a UT was a mistake.

Everyone was a bit shocked. I told him he was very powerful and should give us what we were asking for. The bureaucrats were quashing our representatives. He said he would empower the council. I said he should give us an Assembly instead. He refused.

Tell us more about how the employment issue was resolved.

They said there is no public service commission in any UT. We said J&K has one. They said it was done under the Jammu and Kashmir Reorganisation Act, 2019 at the time. We said that Ladakh and J&K are children of the same mother. How can you differentiate between Jammu and Kashmir and Ladakh? We have the second-highest unemployment rate. In principle, they promised to amend the Reorganisation Act and extend the public service commission to Ladakh.

Why are you asking for the sixth schedule?

The sixth schedule is in force in Mizoram, Meghalaya, Tripura and Assam to protect their tribal population, ethnicities, cultural identities and environment. Ninety-five percent of our population is tribal, and some ethnicities and languages are endangered. Earlier, we had four representatives in the J&K assembly. The government has no right to take away our representation. They should give representation if they want to empower Ladakh. Do not snatch it away. If J&K can become a state (Shah has said statehood will be restored at the appropriate time), then why not Ladakh? The government is not ready to discuss the sixth schedule and statehood issue. That is a problem.

The ST commission (the National Commission for Scheduled Tribes) has recommended (in 2019) that Ladakh be included in the sixth schedule. It was part of the BJP’s manifesto in 2019 to include Ladakh in the sixth schedule. The BJP, in the 2020 Leh council election, promised to include Ladakh in the sixth schedule. Is breaking those promises, not a betrayal?

Why are you not accepting Article 371?

We have not accepted Article 371. The difference between the two is that to repeal the sixth schedule, you need a two-thirds majority in Parliament, and it is a provision specifically for tribal areas. 371 is in many far more developed states than Ladakh and is not that strong. Also, the sixth schedule is already part of BJP’s manifesto. We know that after the 370, the constitutional provision that can give the most protection is the sixth schedule.

If they do not budge, what is the solution?

The solution is to restore democracy by giving Ladakh a legislature and a sixth schedule. The BJP promised this, and it is what the people want.

You have an autonomous body—the Ladakh Autonomous Hill Development Council in Ladakh and Kargil—to oversee local affairs. Is that not enough?

The problem is that there are no business rules for the hill council after four years, and the functions of the secretaries (with the central government) and the councillors have not been decided. The Act of the Hill Council says the council's chairman will have the powers of a cabinet minister, and they will have four executives with the power of a state minister. But what happens now is that if the chairman gives an order, the secretaries reject it. They don’t listen. The chairman of the hill council is powerless. They say themselves they are disempowered. The hill council only gets six percent of Ladakh's 6,000 crores annual budget—everything else is with the bureaucrats. On the allotment of land, the hill council has all the powers, but in practice, they cannot allot two kanals of land. There is a law here under which you could take barren land and till it. The tehsildar would make the report, but now all the powers have been given to the district magistrate. The DM does not go to each person to do a survey and give a report. This is then a kind of systematic disempowerment of the people and to take away the land from the people. We want Ladakhis to govern the people of Ladakh.

What is the difference in how they functioned before and after the abrogation?

Before the abrogation, the hill councils controlled their district's governance. This has been snatched away. The secretaries have a lot of influence. The other thing is that the budget will be in their hands. It was a non- lapsable fund. Now, the funds get lapsed. Ladakh has a short working season, so all the money can’t be spent. First, they had the power to transfer government employees. Now, if they do, the secretaries transfer back.

Ladakh was not significantly different in terms of development and opportunities even before the abrogation.

Our people were part of the state. They had the power to choose the chief minister of the state. Any cabinet decision of the government would have a representative of Ladakh. We are not part of any decision-making or policy-making. Before 370, our land and cultural and ethnic identities were protected. We hear that 20,000 acres of land will be given for a solar project in eastern Ladakh. The revelations of the electoral bonds show that a company named Megha Infra (Megha Engineering Infrastructure Limited) has purchased Rs 966 crore worth of bonds. That company is working on the Zojila tunnel. We don’t know what is happening, how much land is going, and how settlements have been reached. At a time when airports and railway stations are being sold, we are afraid that Ladakh’s resources and land will be sold to big corporations. We no longer have the protection of 370 and 35a.

The government has said that no outsider has bought land in Ladakh, and no companies have invested in it since it became a UT.

But it could happen at any time. There is no protection. I read a report recently that 20,000 acres of land in Ladakh has been given away for solar energy.

Sonam Wangchuk previously backed Ladakh as a UT.

Sonam Wangchuk does not represent any political or religious body. He is individually supporting the cause. The demand for a UT was not of all Ladakh. A section of society demanded UT with the legislature, but a large section was against the bifurcation of J&K and the abrogation. This narrative that all Ladakh was asking to be a UT is untrue. It was the BJP that first brought the sixth schedule in their manifesto. Now, people are asking the government to fulfil your promise.

After the abrogation, there were two camps: the Muslim camp in Leh and the Buddhist camp in Kargil. How did these camps come together?

When we realised the bureaucracy had taken over Ladakh and we had no say and were not being heard, the people in Leh realised that they had been betrayed. The people of Kargil knew this, and that is why they were protesting in August 2019. The common threat, the common security, brought us together. Today, the people of Ladakh say our future is threatened, and we must come together to save it. There was a dispute at a Buddhist monastery in Kargil that both sides resolved amicably after 42 years. This moment is not just about Leh or Kargil. It is about Ladakh. If we don’t work together, we won’t be able to save Ladakh from the corporations and bureaucracy taking over. We want democracy and a voice.

Was it difficult to bring both sides together?

Initially, there was hesitation. On the one hand, we were against the abrogation of 370 and the restoration of statehood. On the other hand, UT was being celebrated. So, it was difficult for both sides to come together and put their demands. But at the end of the day, our future is at stake—the future of our youth. Everyone felt there was a threat to Ladakh. Our concerns broke all the other barriers, and we came on the same page.

Is it also a better atmosphere with both communities working together? Have religious tensions decreased?

Yes, a whole lot. Whenever there is something to discuss with the government, both sides discuss it first and together decide how to move forward.

How frustrating is it that the media does not cover what goes on in Ladakh the way it should be?

It is frustrating. Ladakh gets covered when India and China have a problem, a natural disaster, weather event, or Pakistan. But media do not give space to the people who live here. But the independent journalists and media in J&K do cover us. But the mainstream media, the big houses, do not cover us, which is sad.

(Betwa Sharma is the managing editor of Article 14.)

Get exclusive access to new databases, expert analyses, weekly newsletters, book excerpts and new ideas on democracy, law and society in India. Subscribe to Article 14.