Updated: Jan 24

Srinagar: On the morning of 9 April 2017, 11th-standard student Akeel Ahmad Wani, 16, had gone out to buy medicines for his mother’s ailing heart. He never returned.

The roads were closed because of general elections, so Akeel used an alternate route to reach a medical store. On his way home, said his father Mohammad Amin Wani, Akeel ran into boys throwing stones and was killed when paramilitary forces fired on them.

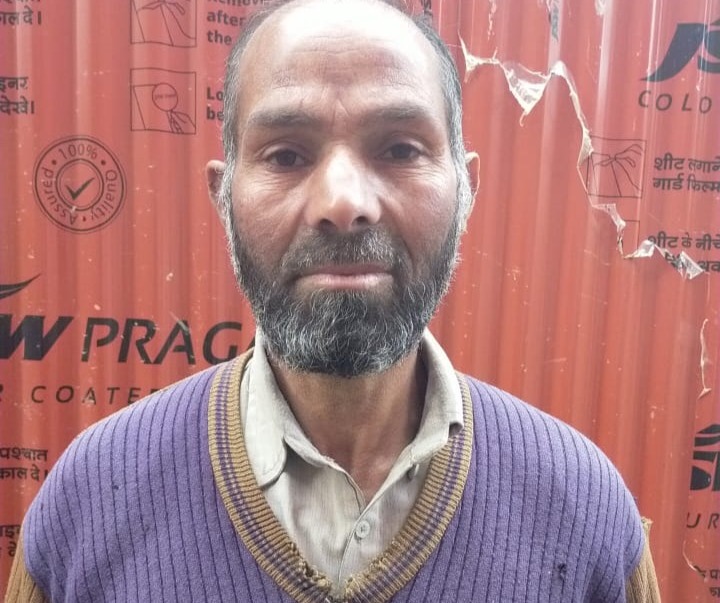

A farmer, Wani denied a police allegation that Akeel, who had no police record, was among the stone-throwers.

“The bullet hit my younger son in the face,” said Wani. “I couldn’t muster the courage to look at his face. When I look at his photo, I curse myself for sending him out to buy medicine. I have only two sons and he was the youngest, too young to die.”

Akeel was among nine civilians—the others did not have police records as well—and an unknown number injured that day as polling was underway, despite a separatist boycott call, in the Jammu and Kashmir (J&K) districts of Srinagar, Ganderbal and Budgam, part of the Budgam parliamentary constituency.

Among the others who died on 9 April 2017 were carpet weaver Nissar Ahmed Mir, sawmill driver Shabir Ahmed Bhat and 12th-class student Amir Manzoor Rasrey.

Later that day, former J&K Chief Electoral Officer Shantmanu (he uses only one name) told reporters of 200 violent incidents in the constituency, mostly in Budgam district, including stone-throwing, petrol-bomb attacks, a polling station and vehicles set ablaze.

“It was not a good day, as you know,” Shantmanu had said.

Two days later, M M Shuja, a human-rights activist, petitioned the State Human Rights Commission (SHRC) for an impartial investigation into the killing of the nine civilians and sought compensation for their families.

“No standard operating procedures was (sic) followed nor any mob control mechanism was put in place,” said the petition (a copy is with Article14). “When there was a reasonable belief (sic) of boycott, the forces should have been extra alert. But instead, a reign of terror (sic) was unleashed by the forces resulting in scores of deaths of unarmed civilians.”

The petitioner alleged that no order from any magistrate was obtained “nor names of sector magistrates were notified and the protestors were responded (sic) by bullets”.

Justice (retired) Bilal Nazki, formerly of the Bombay High Court and chairperson of the SHRC, ordered an inquiry on 14 November 2017. That inquiry was completed in July 2019, but it took the J&K police 11 months to submit their version of events, a lag that, many alleged, helped delay and eventually deny justice.

On 5 August 2019, J&K was reduced from a state to a union territory, and the SHRC ceased to exist on that day, ending hearings into the 9 April 2017 shootings. Akeel’s case file now lies in a bag in a Srinagar room. It is unclear if it will ever be produced again.

“In the [Jammu and Kashmir Reorganisation (Adaption of Central Laws)] order that was notified in March this year, the order states that the National Human Rights Commission will hear the day-to-day cases from Jammu and Kashmir,” said Achal Sethi, secretary of the Jammu and Kashmir law department. “However, the order does not mention that the previous cases the SHRC was handling will be forwarded to the NHRC."

“This particular case was one of the important cases that the commission was handling,” said one of the members of erstwhile SHRC, who spoke to Article14 on condition of anonymity. ”The investigation wing of the commission submitted its report a few weeks before the commission was closed. It is unfortunate that we could not provide justice to the families.”

Established in August 1997, the SHRC had a recommendatory, supervisory, advisory and supportive role in human-rights matters. In 2007, the government created an investigation wing for the SHRC, headed by an inspector general of police. SHRC investigators had carried out inquiries that established state complicity at, among others, Srinagar’s Gaw Kadal bridge, where paramilitary forces killed 52 and injured 250 on 21 January 1990.

They Were Throwing Stones: Police

With the families of civilians killed claiming they were not throwing stones, the police believed otherwise.

An “unruly mob carrying lathis, bricks and dangerous weapons” tried to enforce the election boycott and threatened voters, said the original police report filed in January 2018, a copy of which is with Article14.

“The unruly mob, with an intention to kill, pelted stones heavily and injured security forces and few polling officials,” said the police report. “The (sic) government vehicles were also damaged, and they tried to snatch the weapons of (sic) the security officials.”

The police said security forces fired tear gas but failed to disperse the mob and “in self defence fired few (sic) rounds” to save election officials and voting machines.

This is the report that said Akeel was part of the mob attacking the police, as were the eight other young men shot dead that day, seven in Budgam and two in Ganderbal.

They Were Not Part Of The Mob: SHRC

The SHRC’s investigation, conducted by SHRC investigating officer Naseer Khan, however, incriminated the police and absolved the nine men killed.

Released on 25 July 2019, the SHRC report said “killed civilians were not part of any unruly mob nor were involved in any kind of criminal / subversive activity as reported by concerned police (sic)”.

“It is clearly been (sic) established that the killed civilians were not pelting the stones when they received the bullet injuries,” said the SHRC report. “It is also established that all the killed civilians received the injuries on the vital parts (sic). It was also established that no standard operating procedure was observed by the security forces on ground.”

“The antecedents and previous involvements of all deceased were collected from concerned police stations and nothing adverse was found against them,” the report said.

For instance, Nisar Ahmad Mir, the carpet weaver—and stone-thrower, according to the police—said the SHRC report, “was a gentle person and was engaged in carpet weaving to earn livelihood”.

Quoting eyewitnesses, including election officials, the SHRC report said security forces indeed “fired in self defence” when a mob was throwing stones on polling booths from a hilltop. Window panes were damaged and Mir, “while on his way home, was hit by a bullet”, said the report, which cited a post-mortem to establish he was shot in the head.

In the case of Akeel, the report said, security forces “were not properly equipped with anti-riot guns and tear smoke shells”. As stone-throwing continued, the security forces fired and a bullet hit Akeel, who had no previous police record.

In the “totality of the circumstances, it was established that this civilian death could have been avoided if proper security measures could have been taken by the district administration who were aware that a poll boycott call had been given by the separatist leadership”, said the SHRC report.

The report said sawmill driver Bhat was on his way to pray when killed; class-12 student Rasrey was returning from spraying pesticide at a apple orchard and also was on his way to a mosque; and the others, Faizan Ahmad, Adil Ahmad Sheikh and Umer Farooq Ganai, Muzzafar Ahmad Mir, were not part of the stone-throwing mob.

‘I Remember Every Bit Of This Case’

“It took me a year to investigate this case,” Naseer Ahmad Khan, the investigation officer of the erstwhile SHRC, told Article14. “I spoke to the polling staff, teachers, peons who were at the school (which had been converted into a polling booth) sectoral magistrate, zonal magistrate, tehsildar, police and everyone who was an eyewitness in the case.”

Khan’s report recommended monetary compensation, which had not yet been specified, and jobs for the next of kin.

“But before the commission could pronounce its judgement, it was closed,” said Khan. “I remember every bit of this case; I know the boys were innocent. I know the firing was deliberate, (and that the) killings could have been avoided.”

A week after the SHRC was shut on 31 October 2019, Wani, Akeel’s father, went to the commission to attend a hearing of his son’s case but soon left for home after learning the Commission was closed, likely never to reopen.

While the government, as we said, was not bound to accept the SHRC’s judgments—for example, the State ignored its order to pay Rs 10 lakh as compensation for an army major who used a civilian as a human shield in April 2017—the Commission offered succour and closure of sorts to those who could not afford navigating the justice system.

“The commission was the last hope for people like me who don’t have sources to fight the case in a court,” said Wani, who travelled 40 km to Srinagar for every hearing, a journey he made 12 times. “With its (the Commission’s) closure the hope for justice has also gone.”

Another father echoed Wani’s despair.

“Now who will prove my son was innocent,” said Mohammad Ashraf, father of Nasir Ahmad Mir, the carpet weaver. “No one can understand the pain of a father who has lost his young son. The SHRC was a hope, but now all those hopes are shattered.”

“I thought justice will be done, my son will be proven innocent,” said Amin, “But now I have no expectation from anyone.”

(Shafaq Shah is a journalist based in Srinagar)