Updated: Jun 21, 2020

Bhopal: Santosh (name changed), 21, from the Adivasi Gond tribe, was arrested by Bhopal police on suspicion of stealing bells from a temple in the city in April 2019. He spent seven months in jail before the Madhya Pradesh High Court granted him bail in November 2019.

It was only the beginning of Santosh’s problems. Even after he was released on bail, various police stations in Bhopal continued to hound him. In December 2019, Santosh was picked up again, this time by the police from Govindpura police station in Bhopal and arrested on suspicion of being involved in a theft.

Without sufficient grounds to arrest him, the police then sent Santosh’s case to the office of the Sub-divisional Magistrate (SDM), with a recommendation that it carry out proceedings against him under a section of the law that empowers magistrates to require so-called “habitual offenders” to provide “security”—a fixed deposit, land title papers or title documents for any other assets—to ensure “good behaviour”.

It was at the SDM office that Santosh met an advocate who promised his release for a certain fee —after all, Santosh had a prior record of cases. He finally left after the magistrate made him execute a bond by providing a monetary guarantee promising his ‘good behaviour’. But there was, indelibly, another record of his criminality.

In Kota, Rajasthan, 60-year-old Rajkumar (name changed), from the Pardhi tribe, was arrested for allegedly hunting 108 teetars (partridges). A decade later, he continues to travel to Rajasthan from Sehore in Madhya Pradesh to attend hearings as the case drags on.

“When I was arrested, the other Pardhi men with me ran away,” he said in Hindi. “I was in jail for a month before being granted bail. I have been travelling to Rajasthan since to attend all the hearings. The lawyer charges about Rs 400-500 as fees for each hearing and my conveyance comes up to Rs 2,000.”

Colonial To Modern Law, The Same People Suffer

The everyday policing of marginalised communities, including those from denotified tribal communities and nomadic communities, is not uncommon. As lawyers and researchers based in Bhopal we have worked on and been associated with several such cases. These are our findings and analyses.

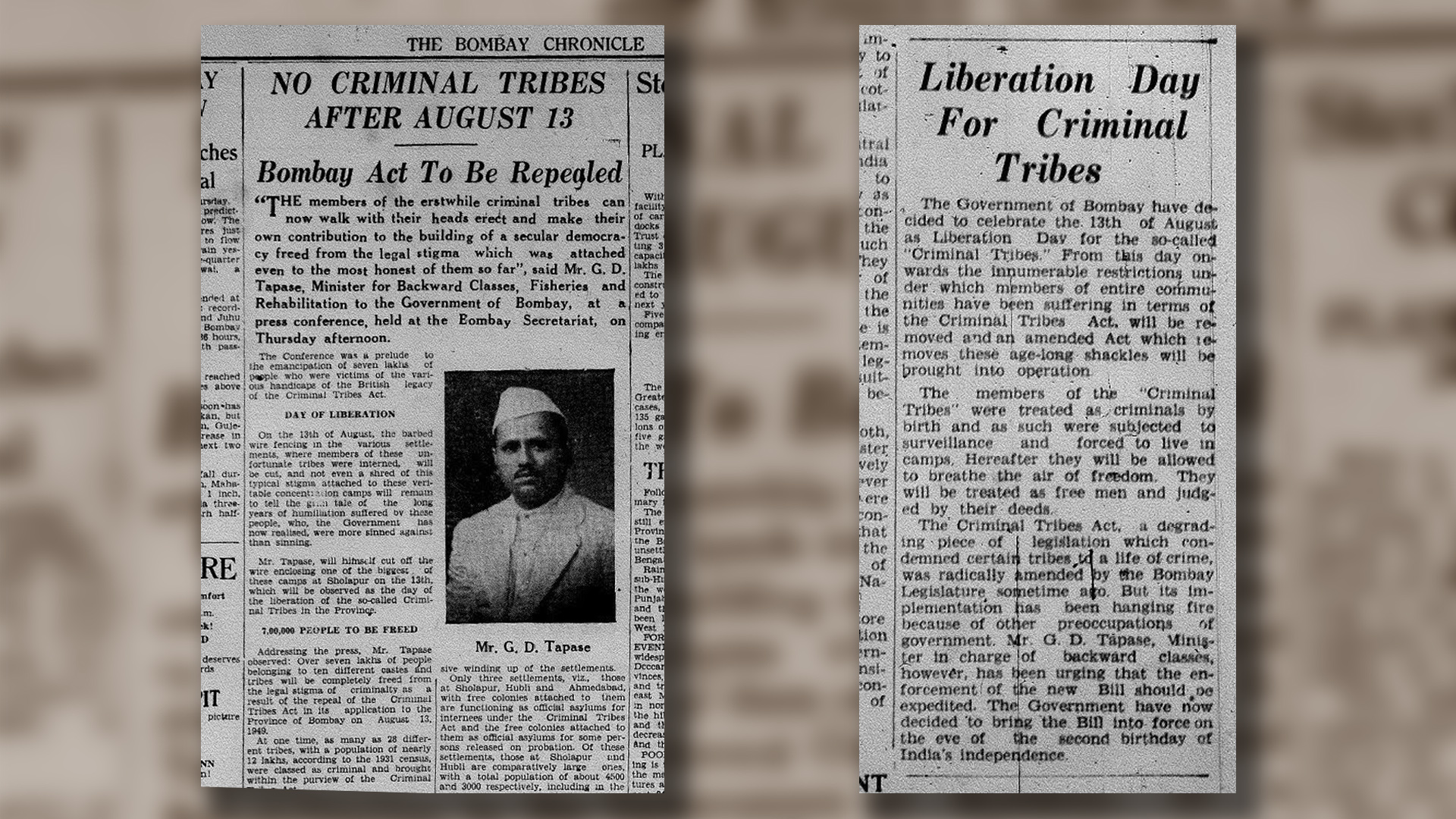

Denotified tribes are communities once classified ‘criminal’ by a 19th century British law, the Criminal Tribes Act of 1871 (CTA) that gave the state wide powers of surveillance. Although this law was repealed in 1952, the stigma of criminalisation and the targeting of these communities by the police continues. Police attitudes are reinforced by a legal regime designed for 'habitual offenders'.

Taking into its sweep, nomadic tribes and semi-nomadic tribes as well some settled Adivasi, Dalit and minority communities, the term ‘habitual offenders’, is sustained by attitudes, law and informal practices.

Several of these communities are not included in the list of Scheduled Castes (SC) or Scheduled Tribes (ST). The Pardhi community, for instance, is not categorised as either in several districts of Madhya Pradesh, including Bhopal. Nomadic Muslim communities such as Kasais are also bereft of such recognition. This denies them protection under the Scheduled Caste/Scheduled Tribe (Prevention of Atrocities) Act, 1989 and makes these communities vulnerable to police violence.

Criminalisation by the state also feeds a casteist society’s disposition to collectively punish people from denotified and nomadic tribes for crimes. The most recent example is the incident in Palghar, where two people from the Gosavi nomadic community were among the three killed when they were apparently mistaken as thieves. Palghar is only the latest of several such incidents that occur every year.

It is against this background that the persecution of denotified tribes through criminal law needs to be understood. Through a three-part series, we will both underscore the substantive laws and procedures under which these communities are targeted by the police and also highlight points of necessary interventions.

In the first part, we look at laws such as the Wildlife Protection Act, 1972 (WPA), anti-beggary laws, excise laws, and cattle slaughter laws, among others, which have penalised the traditional occupations of these communities. Based on our experiences, we try to identify the problems of the criminal law response, covering the above laws as well as provisions related to dacoity— in particular those that create inchoate offences i.e. crimes of preparation, attempting and conspiring. We also look at the problems with ancillary offences such as abetment, possession and the transportation of something primarily criminalised.

In the second part, we will write about the procedural tools that the police and district administration use for targeting communities including habitual offenders’ provisions, bonds for good behaviour and over-arrests, as well as the problems of the wide discretion in using these tools available with the state.

We will conclude the series with a larger picture of this criminalisation industry, which includes torture and extortion of money by the police as well as the nexus between them, the lawyers and the judiciary, positing this as an unexceptional everyday reality of the system.

Where Traditional Livelihoods Are Criminalised

Substantive criminal laws that exist today are fragments of the colonial legacy of regulating traditional employment, enforced by a deeply casteist system. These include the WPA, the Indian Forest Act, 1927 (IFA), the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals Act, 1960 (PCA), excise acts, and anti-beggary laws. This has now come to include cattle slaughter laws as well.

Pardhis traditionally lived in the forest, hunting teetars and rabbits and utilising forest produce for subsistence. The colonial-era forest and wildlife protection regimes displaced them from the forests and many have had to migrate and settle in cities.

Despite their large numbers, teetars are protected by the WPA. Hunting them or keeping them in captivity can result in prison sentences of up to three years, in some cases up to six. It is hard to dispute the importance of animal conservation by law, but one needs to delve into a deeper inquiry whether all such regulation requires this level of sentencing by criminal law —or even if all animals in the schedule today belong there.

The England & Wales Law Commission, for instance, recently explored the option of reducing reliance on criminal law for wildlife protection and recommended “an appropriate mix of regulatory measures such as guidance, advice and a varied and flexible system of civil sanctions such as fines and bans”. It is important to ask if conservation can be carried out without igniting the state’s criminal law and casteist instincts.

“We Pardhis have been traditionally hunting and selling teetars, but now everything has come to a standstill,” said Rajkumar.

A report on Scroll by researchers Samriddhi and Geetanjoy Sahu compared the prosecutions under wildlife and forest laws with pollution laws to find that while the former was geared towards marginalised communities, the latter was aimed at corporations.

The report found that between 2014 and 2016, there were 12,584 cases filed under the Forest Act and 2,458 under the Wildlife Protection Act compared to just 681 under various air, water and pollution acts and the Environmental (Protection) Act, 1986 combined.

“While they rarely punish industrial polluters and illegal miners, pollution control officials often deploy the full might of the law against the deprived communities that are dependent on natural resources for livelihood such as the adivasis," noted the report.

Similarly, crackdowns under the WPA and the PCA on the sapera, madari and qalandar communities that traditionally rely on snakes, monkeys and bears for their livelihood have destroyed traditional ways of life with punitive jail terms without rehabilitation.

The cattle slaughter laws create similar problems. Amendments made to these laws in most states since the 1990s have criminalised not just slaughter but also the transportation of cattle for slaughter as well as the possession of beef. Madhya Pradesh enacted a stricter version of the cattle slaughter law covering these aspects in 2004.

While transport of cattle for non-slaughter purposes is not criminalised, the transport for the purpose of slaughter is. The reversal of the onus of proof under law—the accused must now prove that the cattle being transported is not for slaughter—a prejudiced police and pressure from cow vigilante groups is resulting in the extinguishing of this trade. Those most affected are the Kasai (traditionally butcher) community of which a large part is classified as nomadic in Madhya Pradesh and other states. It also affects other communities, both Muslims and Dalits, involved in the meat trade and cattle transport.

This carceral project—the phenomenon of the overuse of criminal law and incarceration by the state particularly against certain communities—also extends to implementation of excise laws. At 81 per 100,000 persons, Madhya Pradesh has one of the highest rates of cases registered under the Central Excise Act, 1944 according to the National Crime Records Bureau, 2017. The rate of cases under the state excise laws is reported to be even higher. Again, most of those affected are people from various denotified tribes including Kanjar, Sansi, Kuchbandiya and Rai Sikh communities. They have been imprisoned for months and fined thousands for what should be considered a minor infraction.

Disparate Impact Of The Same Laws

It is argued that the disparate impact of these laws on certain classes of people -- in particular on their freedom of trade and right to preferences of food -- are disproportionate and unconstitutional. Previously, the disproportionate impact on a constitutionally protected class has been a ground for reading down of a criminal offence in Navtej Singh Johar v. Union of India [(2018) 10 SCC 1].

This trend of persecution is also seen in the case of offences ranging from theft to robbery; housebreaking to dacoity. The Thuggee campaigns of the early 1800s were the British government’s first concerted effort to crack down on dacoity and, for the first time, some communities, particularly denotified tribes were identified and stigmatised as ‘criminals’.

Today, even preparing or planning to commit offences such as dacoity, robbery and housebreaking are criminalised by the Indian Penal Code. Since these are crimes not yet committed, but only in the planning, the burden of evidence on the police for these cases when they come up for trial is relatively low. FIRs, or first information reports, are often made up of fanciful stories of the arresting police officer’s bravery and tact, as seen in the FIR below.

After a rape near Habibganj Station in Bhopal where the police had initially refused to register an FIR, dozens of scrap dealers, all Pardhi men, who fit the description of the perpetrator were rounded up. They were detained illegally for a day before new people were identified and accused. Following this, the police then moved the 20-odd Pardhi men in groups of four to different police stations registering FIRs against them for belonging to a gang of thieves (section 401). The trial in these cases is still underway two-and-a-half years later.

Two days after he was released on bail, Santosh was arrested again, this time for the illegal possession of a knife under the Arms Act, which criminalises even the possession of certain knives and is among the easiest offences to charge a person with. Police claimed to have received a tip off from an informant. In Bhopal, it is hardly uncommon to see people picked up without cause by the police, subjected to extortion and charged under this section. One FIR is identical to the next one, with striking similarities as to the length of the knife and the role of the police informant.

These are instances that warn us against the tendency to imprison and, worse, punish extra-judicially. When it comes to offences that are still in the planning and have not yet been committed and regulatory offences, one needs to nip instincts to incarcerate and jail. We are presently in the midst of a slide towards over-criminalisation and over-punishment, with ancillary offences such as possession and transport being criminalised as well as procedural screws in the form of search and seizures and onus of proof reversals being tightened.

There is an urgent need in criminal justice discourse to acknowledge and question this slide. In the second part of this series, we will expand on how these procedural tools are used to perpetrate violence against denotified tribes.

This is the first of a three-part series.

Next: Why Charan Singh Bolts His House From Inside And Out Before He Sleeps.

(Ameya Bokil and Nikita Sonavane are lawyers and co-founders of the Criminal Justice and Police Accountability Project, or CPAProject, a research -litigation intervention in Bhopal. This article is derived from their experience of working on the issue of criminalisation of certain communities by the criminal justice system, and decarceration. Issues covered in this article are also the subject matter of the curation for the Detention Solidarity Network (DetSolNet) on Twitter.)