Mumbai: In May 2013, eight unarmed Adivasis, including four minors, were killed by security forces in Edesmetta village of Bijapur District in southern Chhattisgarh. They were allegedly Maoists, an accusation since questioned after a judicial enquiry into the incident.

The committee, headed by Justice V K Agarwal, a former Madhya Pradesh High Court judge, submitted its report in September 2021 and called the incident a “mistake”, saying that security personnel “may have opened fire in panic”. That “panic” led to 44 rounds of gunfire against eight unarmed Adivasis—a paramilitary soldier was killed too, but that was likely by friendly fire.

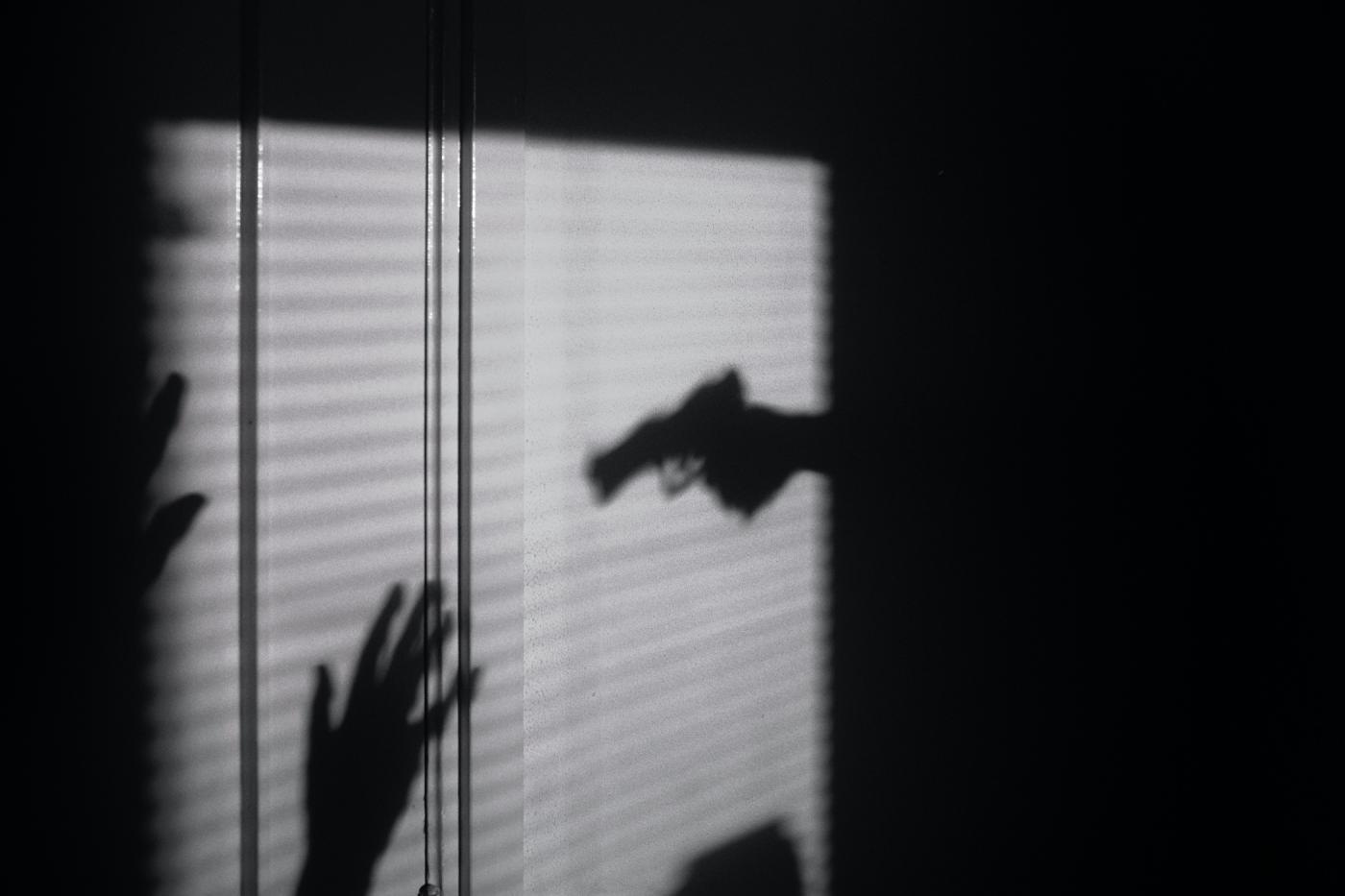

Such “encounters”, as many extrajudicial killings are called, barely shock the conscience of Indians, a people who have become accustomed to and often even approve of, violence by the police and security forces. We live in a society where such “encounter” killings of alleged rapists or alleged gangsters are celebrated by the public, in an almost schadenfreudian sense of revenge justice.

Public Perception Of Police Violence And ‘Encounters’

A 2018 survey of 15,563 people conducted across 22 Indian states and UTs by Common Cause and Centre for Study of Developing Societies (CSDS), The Status of Policing in India Report (SPIR) 2018 revealed that one out of two people condoned the use of violence by the police.

The survey asked the question: “There is nothing wrong in the police being violent towards criminals. Do you agree or disagree?” There were only four states where the majority seemed to reject police violence—Himachal Pradesh, Odisha, West Bengal and Nagaland.

A subsequent 2019 survey of police personnel revealed more troubling attitudes. One in five police personnel felt that killing criminals is better than a legal trial, and three in four believed that it was justified for the police to be violent towards criminals.

“Compared to other States, police personnel in Chhattisgarh, Bihar, Nagaland and Karnataka are more likely to report that they would rather use extrajudicial means to resolve matters,” said the survey. “They are in favour of punishing the criminals themselves, instead of going through the process of a legal trial.”

The use of the word “criminal” here is instrumental to understanding our attitudes towards police violence and killings. While the law states that a person is innocent until proven guilty in the court, the larger public sentiment bestows powers of judgement upon the police and security officials themselves.

Even though neither law nor morality sanction such behaviour even if a person is a recognised criminal, it is often that those at the receiving end of such violence are not even guilty of the crimes of which they are accused.

This unfettered discretion that the police and security personnel have bestowed upon themselves gives way to disproportionately more killings of Muslims, scheduled castes and scheduled tribes by the security forces.

Discrimination And Violence

The SPIR report presented evidence of both public perceptions of the police being discriminatory towards SCs, STs and Muslims and biased police attitudes towards these communities.

Adivasis are the most distrustful of the police among all caste and religious groups, while one in four people believe that police discriminate on the basis of caste: 19% of people polled felt that police discriminate on the basis of religion, with Muslims most likely to have this opinion. One in two people said that police discriminate on the basis of class.

Up to 38% believe that Dalits are falsely implicated in petty crimes and 2% believe that Adivasis are similarly implicated in charges of being Maoists. About one in two Muslim respondents felt police falsely implicated them in terrorism related cases.

The attitudes and opinions of police officers are not very different. One in two police personnel believe Muslims are naturally prone to committing crimes, 35% believe the same of Dalits and 31% of Adivasis.

With such views, it is unsurprising that “encounter” deaths too, like incarceration, are disproportionately higher among these communities.

According to data from 2017-2020 nearly 37% of those killed in “encounter” deaths in UP were Muslims, who made up 19% of the state’s population.

While disaggregated data on fake encounters across caste and religion are not available at the national level, it would not be entirely unsubstantiated to hypothesise that they are disproportionately targeted against these already disadvantaged communities.

Gaps In Official Data

While high-profile cases may surface on the media intermittently, aggregate data on fake encounters is scant and unreliable because no country wants to openly, officially admit to using extra-judicial means, in defiance of the rule of law.

For this reason, too, the data are often also contradictory.

According to a March 2018 reply by the home ministry to a question in the Rajya Sabha, there were six alleged fake encounters in 2017-18 in UP. However, according to the Nation Human Rights Commission (NHRC), 44 cases of deaths in police encounters were reported that year in UP.

According to other unofficial sources, even the NHRC data is an underestimation. For instance, according to data collected by the National Campaign Against Torture (NCAT), there were 111 custodial deaths in 2020, against 90 deaths registered by the NHRC.

The NCAT report noted how, as most crime indicators fell significantly over the lockdown, the number of custodial deaths increased, with over one suicide every week because of alleged torture in police custody.

Justice Delayed And Justice Denied

Justice to victims of fake encounters is often too little, too late.

While it took the inquiry in the Chhatisgarh case we mentioned earlier seven years to submit its report, the conviction of police personnel came 25 years after the 1991 Pilibhit fake-encounter case of 10 Sikh pilgrims. These are just two of the many cases that took nearly a decade, often much more, to be decided.

While in a few cases justice was delivered, even if it was delayed, many more such incidents go entirely un-investigated. This is particularly true in conflict regions such as the states in which the Armed Forces (Special Powers) Act (AFSPA), 1958, has been enforced or the states with left-wing extremism (LWE), which witnesses a high number of “encounter” killings by paramilitary forces, armed forces and police.

According to the Status of Policing in India Report 2020-21 Volume I—Policing in Conflict Affected Regions, 6% of those in conflict regions knew victims of fake encounters involving paramilitary forces or the army, while 8% knew victims of fake encounters involving the police. The proportion of respondents who knew victims of such incidents is higher in LWE-affected regions than the insurgency-affected regions of India's northeast.

Due to the impunity granted to security officials under laws such as AFSPA, thousands of cases of encounter deaths were not investigated for years. In 2017, a Supreme Court bench ordered a CBI probe into 1,528 cases of alleged extrajudicial killings from 2000-2012 by security forces and police in Manipur.

The Court noted that despite NHRC guidelines stating that FIRs should be registered in all cases of encounter deaths, no FIR was registered against any uniformed personnel or member of the state police. Instead, charges have been filed against the deceased for alleged violations of law.

Across India, there is evident a systemic failure of providing justice to victims of fake encounters and a glaring disregard for procedural guidelines.

Against 111 cases of fake encounters documented by the NCAT, or even the more conservative 90 cases documented by NHRC in 2020, only three cases of encounter killings were registered in the year 2020, according to data from the National Crime Records Bureau. Two police personnel were arrested for “encounter” killings in the year and none were convicted.

‘Encounter’ Killings As A Political Tool

Even while hiding under-reporting data political leaders do not fail to endorse such practises and capitalise on public mistrust in the justice system.

From the UP Chief Minister’s “aparadh karenge toh thok diye jaayenge (If you commit a crime, you will be knocked off)” comment and a tweet from the chief minister’s official account, listing as an “achievement” 430 “encounters” in six months, to Assam CM Himanta Biswa Sarma ordering the police to adopt a “zero-tolerance” approach, fake encounters easily turn into self-congratulatory speeches.

Ethics and legality aside, such declarations and acts do work, if only for political gains. Public opinion ranges from apathy at best to encouragement at worst, as is evident from the survey findings on public perceptions. According to a 2017 study by Daksh, a think tank, the formal judicial system is not the most preferred form of conflict redressal for most Indians.

When asked whom they would not approach, 40% of respondents told Daksh researchers that they would not approach the police; 32% said they would not approach lawyers. “This is a cause of worry as it shows that people do not approach these two fundamental pillars of the justice system when it comes to disputes,” said the study.

Regardless of the lack of faith in the judicial process, constitutional values prohibit both the people as well as law enforcers from taking the law into their own hands. Such killings are antithetical to human-right values, and the political trend of building a narrative to propagate extrajudicial means of serving justice effectively undermines India’s legal and constitutional ethos.

(Radhika Jha is a lawyer and criminologist working with Common Cause and lead researcher of the Status of Policing in India Report series.)