Bengaluru: Anaheeta Pinto came across the quarantine list on WhatsApp, where, she said, “it had become quite the popular little voyeuristic game”—people trying to figure out who around them was in quarantine and checking to see if they were actually at home.

“I was quite shocked,” said Pinto, who lives in a sylvan, prosperous east Bengaluru neighbourhood called Richards Town. "We are socially distant but that doesn’t mean we had to be suspicious of each other. It doesn’t feel like it’s in the right spirit."

The list circulating in Richards Town—where debates broke out about whether the quarantine list was acceptable or not—allows neighbours to spy on each other. “The government is asking people to police each other rather than authorising state/public officials under the proper legal framework for this,” said Apar Gupta, Executive Director at the Internet Freedom Foundation, an advocacy.

As the Coronavirus spreads, so too are quiet invasions of privacy, unhindered by restraining laws. Taking the lead, with relevant justifications, is the government in India's IT capital.

Log on to the Karnataka government’s ‘Corona Watch’ app and here’s what you ought to see: where COVID-19-positive patients in Karnataka travelled, along with date and time, so that those who may have shared the same space with them can go to the nearest hospital to get themselves checked.

So far so good.

But what the app also shows you is this: the home address of all those quarantined--sometimes their office addresses as well--along with details of their family.

Yet, the Karnataka app is not as invasive as some tracking and quarantine apps released by other state governments.

The Andhra Pradesh, Kerala, Tamil Nadu and Gujarat governments have all released apps to enforce quarantine and keep track of the symptoms of the thousands of foreign-returned people statewide. Once downloaded and registered, the apps track the location of the phone and send alerts if the device is moved a certain distance away from its home location, a technology known as geofencing. Another district of TN went a step further with an app that sends random messages to the quarantined person, asking them to take a photo of themselves and upload it on the application to ensure that they have not left their phone behind to step out of the quarantine.

The reports of harassment due to such lists have already begun trickling in.

An app launched by the Government of India is in beta testing phase now: the Corona Kavach is a location-based app that tracks the user’s location every hour to check if they are at risk of being exposed to COVID-19. It will also ask about your body temperature, aches, etc and categorise you as green (health), orange (visit doctor), yellow (quarantine) and red (infected).

The Karnataka app came a couple of days after a contentious state move to release, by district, details of home addresses, departure destinations and quarantine periods of thousands of travellers who flew into the state on and after 8 March 2020, including nearly 15,000 people from Bengaluru. These details are also now available in the Corona Watch app. Karnataka’s next app intends to track the movements of quarantined individuals.

Covid-19 positive tests doubled over six days to 28 March to cross 900 in India, which may only be a few weeks behind the kind of full-blown outbreaks seen elsewhere in the world. While other countries have also struggled with drawing the line between privacy and urgent public-health information during the pandemic, the lack of data protection laws in India makes citizens more vulnerable to privacy invasions than those in other democracies, said experts.

What Karnataka and India currently deploy is the archaic Epidemic Diseases Act, 1897, which “emphasises the power of the government but is silent on the ethical aspects, or human rights principles that come into play during the response to an epidemic,” said a 2016 paper in the Indian Journal of Medical Ethics.

“It would have been good if the Act stated clearly the situations under which the authorities may curtail the autonomy, privacy, liberty and property rights of the people,” said the paper, written by PS Rakesh, an independent public health consultant. He quoted historians to argue that “the potential for abuse was enormous” and that the act has “no provisions that take the people’s interest into consideration”.

Building ‘Social Pressure’

As on 28 March, Karnataka had 55 coronavirus cases and two deaths. With the state government still unsure about the start of community transmission, it began an extensive effort to “contain and discipline” those with recent travel history, many of whom were reportedly violating quarantine, Pankaj Kumar Pandey, Karnataka Health and Family Welfare Commissioner, told media persons during a 25 March video conference.

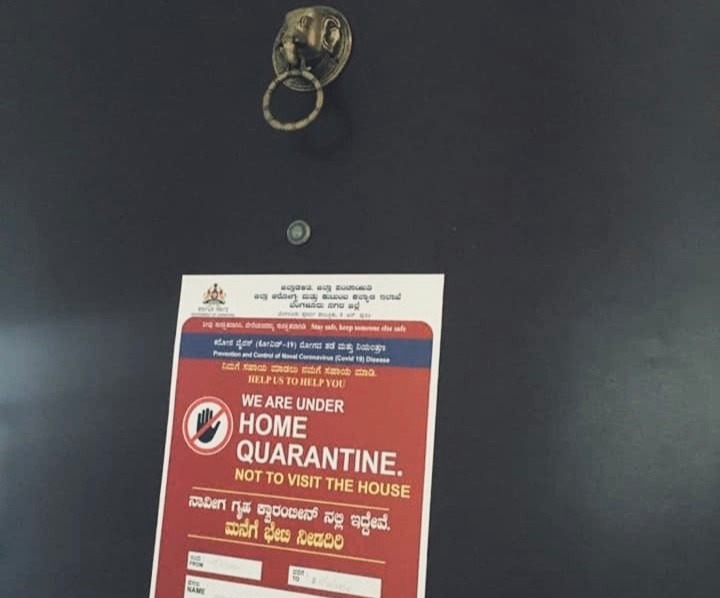

Home Quarantine Enforcement squads are visiting homes of quarantined people to stamp their hands with the end date of quarantine. They paste notices outside homes, so neighbours are informed that their neighbours are not supposed to move out. Quarantine violators are being sent to mass-quarantine centres because the government “had lost confidence in them”, said Pandey. By 28 March, 101 people had been moved from home quarantine to institutional quarantine, based on "complaints received from the public".

First information reports (FIRs) were also filed on 23 and 24 March 2020 against two people found violating self quarantine, with the police invoking sections 269 (negligent act likely to spread infection of disease dangerous to life), 270 (malignant act likely to spread infection of disease dangerous to life) and 271 (disobedience to quarantine rule) of the Indian Penal Code. The Epidemic Diseases Act also allows for prosecution under IPC Section 188 (disobedience to order duly promulgated by public servant).

“People who were supposed to be in home quarantine were roaming around in the streets irresponsibly”, BBMP Commissioner B H Anil Kumar told Article14, when asked why the government decided to release the data. Initially, many believed—as did Pinto in Richards Town—that the information doing the Whatsapp rounds was hacked or leaked. It emerged the government had posted the list on the website of its health department, to “build social pressure”.

In neighbouring Kerala, which in many ways has been setting the benchmark for how to handle the pandemic, when the data of quarantined people was either leaked or hacked, the district collector said anyone sharing confidential information would be “dealt with strict actions (sic)”.

Neighbour Against Neighbour

The new apps and quarantine lists come at a time when people in housing societies and apartment complexes,driven by fear and uncertainty, appear to be turning on each other, and Residents Welfare Associations (RWAs) perpetuate their own versions of policing and discrimination.

There have been cases of those who have returned from abroad, healthcare workers and airline staff being harassed and ostracised by neighbours. This harassment, combined with Section 4 of the ED Act, which says that “no suit or other legal proceeding shall lie against any person for anything done or in good faith intended to be done under this Act”, makes the privacy invasions hard to combat.

Commissioner Kumar said the BBMP “held a meeting via video conference with about 137 RWAs and told them that they should treat these people in quarantine as part of their family and make sure they are not subjected to any discomfort”.

The RWAs were also asked to help out if those quarantined required essential commodities. Pinto, who is also a member of the Richards Town Residents Association, which she says is one of the city’s most active and vocal RWAs, said she knew of no such videoconference that Kumar referred to.

Pinto said she understood the arguments made by some of her neighbours, who contended that the list was valuable in identifying those skipping quarantine and impressing on them the seriousness of violations. But considering that, even conservatively, less than 1% of those under quarantine have violated the rules, the suspicion and paranoia is too steep a price to pay, she felt.

Pinto said she also knew that she was in a minority.

During And After The Pandemic

Most might not care about privacy in the face of this pandemic, but once it is over, will we be able to take back some of the rights we have given the government? Those working in the privacy, legal and related fields think not.

In India there is no law that compels the government to collect data according to the "rule of proportionality" (ask only for data necessary to control a crisis) and to be more accountable for the data it uses, said Aditi Seetha, Counsel at AS Law Chambers.

The Information Technology Act, 2000 - Section 43A (compensation for failure to protect data) and Section 72A (punishment for disclosure of information in breach of lawful contract) are "poor substitutes", said experts. That much is obvious from the lack of considered and critical thought into such actions, said Gupta.

Analysts are not sure that the Personal Data Protection Bill, 2019, as it stands, could have helped. The Bill was introduced in Lok Sabha by the Minister of Electronics and Information Technology, Ravi Shankar Prasad, on December 11, 2019. It was referred to a parliamentary committee, whose report was expected in the last week of the budget session, but has been extended to the second week of the monsoon session of Parliament.

Section 12 of the data bill says that consent is not required in situations of “medical emergency involving a threat to life or a severe threat to the health of the data principal or any other individual”. Consent is not required to process data [“an operation that includes disclosure by transmission, dissemination or otherwise making available, restriction, erasure or destruction”] to undertake any measure to “provide medical treatment or health services during an epidemic, outbreak of disease or any other threat to public health”.

“The normal provisions of the bill are suspended during situations like an epidemic,” said Anirudh Burman, Associate Fellow at Carnegie India, a think tank. "The only stopgap would have been that some authority might have had to pass a notification saying that we are bypassing the requirements of this law because of an emergency.”

“In other jurisdictions like Italy, France or even China which have good data protection laws, the governments have issued specific circulars, mentioning how the data they are collecting will be used,” said Seetha. If the data are found to be used for any purpose other than specified, judicial recourse is available. India lacked this security, she said.

Gupta said he feared that the surveillance measures put into place to counter the Coronavirus would probably persist after the pandemic and likely morph into something more invasive.

“We have seen this happen with the Aadhaar, which was articulated as a project principally to check leakage of rations and ensure targeted delivery of services to underprivileged beneficiaries of government schemes,” said Gupta. "But ultimately it was justified in the Supreme Court as a mechanism to check tax evasion and money laundering."

There appears to be nothing stopping the government from doing something similar with the data and access that it is acquiring in the fight against COVID-19.

(Ayswarya Murthy is an independent journalist based based in Bangalore. She writes on politics, policy and everything in between.)