New Delhi: Secretive political funding by companies and individuals through electoral bonds reached no more than 19 political parties of over 2,800 across India, with India’s ruling Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) alone raising 68% of the Rs 6,201 crore received in three years, reveals a series of interviews and analysis of annual audit reports by The Reporters’ Collective.

The findings run contrary to the widely held belief (here and here) that electoral bonds were encashed by 105 political parties and the BJP’s claim that bonds are an efficient way to allow, in the BJP’s words, “donation to any political party of donors’ choice”.

In 2017 and 2018, petitions were filed (here and here) in the Supreme Court challenging the legality of electoral bonds through which corporate companies and individuals anonymously donated unknown amounts to political parties, with no limits. The Supreme Court on 12 April 2019 asked the Election Commission (EC) to find out and provide information on which parties received electoral bonds worth how much.

The Supreme Court ordered that the information be given in a sealed envelope, a practice brought into vogue by former Chief Justice of India Ranjan Gogoi, so that no one but the judges could review the information.

The EC wrote to political parties asking them to answer the court’s question. Of the over 2,800 political parties registered with the EC, 105 responded, though some questioned the Commission’s logic of seeking reports from all, irrespective of whether they received the bonds or not.

The EC submitted the responses in a ‘sealed cover’ to the apex court in February 2020. The list included seven national parties, three state units of national parties, 20 state parties, 70 registered unrecognised parties—those without a fixed election symbol but eligible to contest elections—and five unidentified entities.

Two years have passed since the apex court last heard the case despite the repeated reminders from the petitioners. The court has not yet opened the sealed envelopes.

Only 17 Parties Got Donations Through Bonds

The Reporters’ Collective has now ferreted out the information in the sealed envelopes by interviewing the heads of 54 of 70 registered unrecognised parties that replied to the Commission, reviewing the letters the parties sent and crunching data from the annual audit report filings of political parties.

Together, these revealed that only 17 political parties of the 105 named in the EC’s sealed envelope got funds through electoral bonds.

Of the 17, BJP got the largest share of the pie—67.9% or Rs 4,215.89 crore of the total electoral bonds purchased between financial years 2017-18 and 2019-20.

Though second, the Congress was a distant dot in the BJP’s rearview mirror, raising Rs 706.12 crore or 11.3% of all bonds encashed.

Biju Janata Dal, at a distant third, got Rs 264 crore. It accounted for 4.2% of the bonds encashed. The rest of the national and state parties got the remaining 16.6% of bonds worth over Rs 1,016 crore.

The BJP, Congress and BJD together cornered 83.4% of political donations made through electoral bonds.

At least two more parties, Dravida Munnetra Kazhagam and Jharkhand Mukti Morcha, received money through the bonds, but the EC has not listed them as having responded to the Supreme Court’s directive.

In its responses to Right To Information (RTI) applications, the government-owned State Bank of India (SBI), the only bank authorised to issue and encash electoral bonds, refused to name the 23 parties that were eligible to receive and encash electoral bonds.

Why Electoral Bond Issue Is In The Supreme Court

Under the Electoral Bond scheme announced in 2017 by then finance minister Arun Jaitley, companies, individuals, trusts or NGOs may anonymously buy as many bonds as they wish, in multiples of Rs 1,000, Rs 10,000, Rs 100,000, Rs 10 lakh and Rs 1 crore, and deposit these in the account of a political party held with the SBI.

Critics have pointed out (here, here and here) that electoral bonds help hide donations from the rich and powerful to politicians and increase the cash chest of political parties, in this case, the BJP. The money goes into extensive advertising campaigns and related electoral expenses, allowing the party to outspend rivals in election campaigns and keep its election machinery running.

On 4 September 2017, the Association for Democratic Reforms (ADR), a nonprofit, filed a petition in the Supreme Court seeking to revoke amendments to key rules under the Finance Act, 2017 that paved the way for electoral bonds. In an interim order in April 2019, the court asked political parties to provide details of funds received through electoral bonds.

The EC, too, wanted the electoral bonds scheme rolled back. It filed a counter-affidavit in the court in March 2019 in response to the petition, expressing its reservation with the bonds.

“This is a retrograde step as far as transparency of donations is concerned,” the EC said in its affidavit. It flagged amendments to four pieces of legislation. It warned that these amendments would bring black money in political funding through shell companies and allow “unchecked foreign funding of political parties in India, which could lead to Indian politics being influenced by foreign companies”.

In contrast to the EC’s concerns, the BJP found the electoral bonds scheme a “path-breaking” and “innovative” way to “cleanse the political system by bringing in clean money”.

When the finance minister sought feedback from parties on the proposed scheme in May 2017, the BJP gave it an enthusiastic review while others expressed their doubts.

Investigative reports published in 2019 by The Collective showed how the union government ignored objections to the bonds from the Reserve Bank of India, lied in Parliament about the EC’s comments, broke the law by allowing an illegal “special” window to encash bonds before the Karnataka state assembly elections and made the SBI accept expired bonds.

The SBI had been caught asking the finance ministry for permission to respond to RTI queries related to electoral bonds despite being an independent public authority under the RTI Act, 2005.

The bank lied in its RTI responses on bonds. It said that it does not have data on how many bonds of each denomination were sold in 2018 and 2019, a claim that was refuted by a clutch of official records that showed that it not only had the information stored in that format but would regularly send the data to the finance ministry.

Recently, the SBI in its reply to RTI queries filed by retired commodore Lokesh Batra said that only 23 of the list of 105 parties submitted by the EC to the Supreme Court were eligible to receive electoral bonds.

The bank, however, refused to reveal the names of the 23 parties citing sections of the RTI Act, which exempt the disclosure of information stored under a fiduciary relationship and those that violate privacy. But these clauses can be invoked only if the public authority concludes that no public interest will be served by disclosing the information.

‘We Have Rs 700 In Our Bank Account’

The Labour Samaj Party of Uttar Pradesh is one of the 70 registered unrecognised parties named in the list submitted by the EC. According to an ADR analysis, the Labour Samaj Party, along with 68 others, is not eligible to receive donations through electoral bonds.

This baffled many, since all the 105 parties listed by the EC were believed to have got money through the bonds. There were news reports on how these parties, mostly based in rural parts of the country with tiny offices and hardly any press coverage, were raking in money through the opaque bonds. The unusual names—Aap Aur Hum Party (You And Me Party) or Sabse Badi Party (The Biggest Party)—attracted media attention.

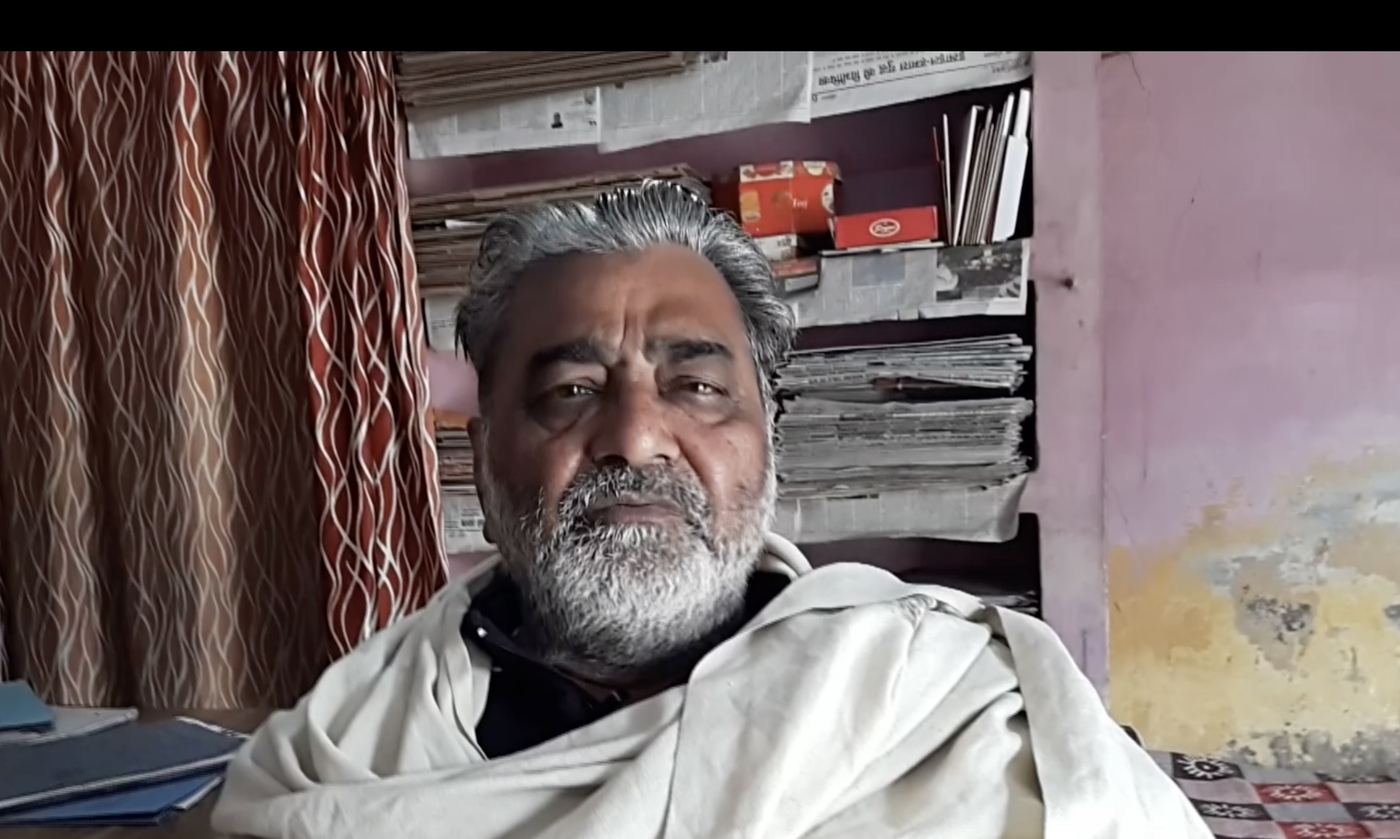

[[https://tribe.article-14.com/uploads/2022/06-June/06-Mon/LetterFromBharatKiLokJimmedarParty.jpg]]

The Collective spoke to heads of 54 of these registered unrecognised parties. Others could not be reached.

“I don’t know what electoral bonds are,” said advocate Baburam, the founder of the Labour Samaj Party. “We haven’t got any donations. I can show you our bank passbook. We have around Rs 700 in our bank account.”

All the party heads we spoke to denied having received a paisa through bonds and shared the responses they had sent to the EC.

Rahul Mehta, the founder and president of Gujarat-based Right To Recall Party, told The Collective that his party didn’t even have a bank account when they received the letter from the EC.

“We were asked to submit a nil report. I confirmed with the state election commission. They said replying to the EC letter was mandatory,” Mehta said.

Mehta’s Right To Recall Party replied to the EC on 30 May 2019 and was subsequently put on the EC’s list submitted in court.

It was the same for the four parties we visited—Delhi-based Praja Congress Party, Ghaziabad-based Hindustan Action Party, Labour Samaj Party and Rashtriya Peace Party. One of the four, the Hindustan Action Party, does not even have an SBI account.

The responses were the same from the 50 registered unrecognised parties we spoke to over the phone.

“Who’ll give parties like ours any donations?” asked Binod Kumar Sinha of the Patna-based Bharatiya Backward Party.

(Shreegireesh Jalihal is a member of The Reporters’ Collective, a journalism collaborative that publishes in multiple languages and media. Poonam Agarwal is an independent investigative journalist with 18 years of experience in television and digital media. Somesh Jha is a former member of The Reporters’ Collective and currently Alfred Friendly-OCCRP Investigative Reporting Fellow, 2022 at Los Angeles Times)