New Delhi: “There is not a single piece of evidence on the record to point out towards the accused persons, as members of the riotous mob behind the incident,” read a local court’s judgment while acquitting six men on 2 August 2024, four years and five months after they were accused of rioting and arson.

Article 14 spoke to four of them—Hashim Ali (58), Abu Bakar(28), Mohammad Azeez (28) and Najumuudin (28)—who lived in Shiv Vihar colony in northeast Delhi, where communal violence raged from 24 February to 25 February, killing 53 people, three-quarters of them Muslim.

They were among over 180 people found innocent during trials over four years after the riots.

Article 14 reported in 2021 that Delhi judges have described the cases following the riots as “absolutely evasive, lackadaisical, callous, casual, farcical, painful to see, and misusing the judicial system.”

In May 2024, Article 14 reported that when discharging a case of rioting, criminal conspiracy and destruction of public property during the 2020 Delhi riots against 11 Muslim men, a judge found that the police had “artificially prepared” the case, using planted witnesses and concocted statements to frame nine of them.

In another Delhi riots case we have reported on that appears to be built on spurious evidence, 13 Muslim women identified as taking part in a protest against India's citizenship law in February 2020 by a secret police informer months after the violence gave more or less identical statements against Gulfisha Fatima, Devangana Kalita and Natasha Narwal, three students activists whom the Delhi police have accused of conspiring to cause the Delhi riots.

The case against the six men was based on the testimony of a neighbour, Naresh Chand, who claimed that a mob, including Abu Bakar, Mohammad Azeez and Hashim Ali, vandalised and damaged his property before setting it on fire.

However, as the court in Delhi in Karkardooma subsequently discovered, there was no evidence to support the claims. The judge said, “I am of the opinion that there is no incriminating evidence against the accused persons.”

They were charged under sections 149 (unlawful assembly), 148 (rioting, armed with a deadly weapon), 380 (theft in dwelling house, etc.), 427 (mischief causing damage of Rs 50 or more), 435 (mischief by fire or explosive substance to cause damage) and 436 (mischief by fire or explosive substance with the intent to destroy dwelling house) of the Indian Penal Code.

If convicted under all of these sections, the sentence may be concurrent (all sentences are served at the same time, so the total time in prison equals the longest sentence) or consecutive (sentences are served one after another, so the total time in prison adds up all the sentences), depending on the judge's discretion. Based on the facts of the case, the sentence could have ranged from two years to life imprisonment.

A Paucity Of Evidence

Hashim Ali spent about 75 days in jail, first in Tihar and later in Mandoli. Abu Baker spent 15 days in Tihar and was transferred to Mandoli Jail.

During the trial, witnesses—including Chand himself—contradicted their prior testimony, and CCTV footage offered as crucial evidence failed to identify the accused.

Abu Bakar, 28, who did part-time masonry work before the Delhi riots, is now unemployed. Due to court hearings, his work dried up, as he had to keep turning down jobs.

Abu Bakar said he feared for his safety because of “growing communal tensions” and is considering getting a passport and working abroad.

Bakar said the case caused a lot of financial troubles for his family.

“I went to jail, and the Covid-19 lockdown was going on. My siblings were studying, and my father, the sole breadwinner, took on all the pressure,” said Bakar. “We had already suffered financial loss in the riots. The trial lasted four years, and we spent money on bail and other legal expenses.”

Bakar said his father didn't tell him they spent around Rs 150,000 on legal proceedings, leading the family into debt.

Bakar said the accusation caused him personal problems in addition to financial ones.

“Due to this case, my entire reputation changed,” said Bakar. “However, my relations with my Hindu friends didn’t deteriorate. We even became close to a Hindu family after the case. They knew I was falsely accused in a Delhi riots-related case, but they never treated me any differently.”

While he was eventually acquitted of the charges, Bakar said, “We got free from the case after four years, but no one can compensate for the lost time and sufferings we have gone through.”

The Neighbour Who Complained

On 23 February 2020, Delhi was hit by communal violence, which lasted for a week. Over 53 persons, primarily Muslim, were killed.

At least 14 mosques were set on fire during the riots.

Abu Bakar said that Naresh Chand’s house is next to the Madina mosque in north-east Delhi’s Shiv Vihar and had caught fire when the rioters set the mosque ablaze.

“I don't know what compelled Naresh Chand to name me,” said Bakar.

The police registered over 750 cases related to the rioting.

According to police data accessed by The Print, 2,094 of the 2,619 people arrested were out on bail as of February 2024. However, the “total number of accused is unclear as many were booked in multiple cases”. The courts acquitted 183 people, discharged 75, and convicted 47.

Of the first 1,753 people arrested at the time, a Delhi Police 2020 report said 820 were Hindus and 933 Muslims.

Of the 53 people killed in the riots, three-quarters were Muslim.

According to a 2020 Delhi Police affidavit, quoted in a report by The Wire, 14 Hindu houses and 50 Muslim ones were damaged, while 42 shops damaged belonged to Hindus compared to 173 owned by Muslims.

The report said this was an “undercount” by the police and that “85-90%” of the houses and “80-85%” of the shops and businesses attacked were owned by Muslims.

Only about 15% of people whose cases have been completed have been found guilty.

“False charges and delayed trials are the most devastating issues many accused persons are facing,” said Abreeda Banu, a Delhi-based lawyer who practices in the Supreme Court. “This leads to serious violations of basic fundamental and human rights of individuals and may in certain cases lead to denial of justice to the prisoners.”

“More systematic updates should be made to run the legal proceedings more quickly and to ensure transparency,” she added.

‘The Past Still Haunts Us’

Abu Bakar’s 20-year-old sister, Gulafsha, was at home when the riots began.

“The situation was dire. There was fire everywhere, and we had no way left to get out,” she said. “The whole sky was black due to the smoke. Those who lived in the outer area had run away, but people like us who lived in the inner regions couldn’t do anything.”

The family were evacuated to Mustafabad, also in north-east Delhi. “I kept informing the police,” said Bakar. “The army battalion came and evacuated us to Mustafabad.”

Abu Bakar said he returned home a week after the riots to find that his house had been broken into and valuables, such as jewellery, worth about Rs 200,000, and Rs 44,000 in cash stolen.

Gulafsha said that Mustafabad was safe for them because it’s a “Muslim concentrated area”, and the Hindus who live there were also very supportive.

“They said that if anything happens, we will protect you. Hence, everyone had a sense of security,” said Gulafsha. “They stayed up all night, guarding us, and all the Gujjars living there protected us. You see, it’s not about Hindu or Muslim. If you are humane, religion doesn’t matter.”

The riots and the subsequent allegations against Bakar continue to affect the family.

“Everything has become normal, but the past still haunts us on important days and festivals, be it Republic Day or Diwali,” said Gulafsha.

“People still run away during such days and go to the homes of their relatives, fearing communal violence, said Gulafsha. “But we don’t leave. We stay here. How long are we going to run away again and again?”

Financial Losses

Mohammed Ajeej is a 28-year-old air conditioning technician.

Ajeej said he was at home during the riots. He was, however, charged with taking part in the violence.

His career was interrupted by the accusations, which sent him into debt.

“This case left me in debt. Going to court required money, and without steady work, I had to borrow funds,” said Ajeej. “To arrange for bail, I even had to take out a loan with interest.”

Ajeej said his work was disrupted as he had to attend court proceedings. His career is yet to recover.

“Before the Delhi riots, I used to earn around 16,000 rupees monthly, but my income decreased due to this case,” he said.

Ajeej said his family had to flee their home during the riots. He said on 25 February, around 4 pm, the houses in the alley behind theirs were set on fire. People started fleeing, and around 6 pm, they left for Chaman Park, where they stayed in a refugee camp.

Ajeej said they moved to a second camp in Eidgah Mustafabad after two or three days. When the camp was vacated due to COVID-19, they were forced to rent a house in Chaman Park.

The fallout of the case continues to affect him.

Ajeej said due to this case, he lost at least five marriage proposals, and his relationships with Hindu friends also soured.

“I had a friend named Govind. Because of this, our friendship deteriorated,” said Ajeej. “We used to meet every day, morning and evening, but since 2020, we've only talked three or four times.”

Forced To Relocate Business

28-year-old Najmuddin Sheikh runs a barbershop.

During the riots, in addition to his home being attacked—a gas cylinder exploded outside his house—his shop was looted. He had started the barbershop only five months before the riots.

Sheikh said that after the incident, Naresh Chand, his accuser and former landlord, refused to rent the shop to him again, causing him significant hardship.

Sheikh claimed that it now gets very few customers because he had to relocate his shop to a predominantly Muslim locality.

Sheikh said he has lost a lot of money since the accusation. He couldn’t afford a lawyer and had to seek help from the Association for the Protection of Civil Rights (APCR), a Delhi-based non-profit organisation, to defend himself.

The APCR national secretary and human rights activist, Nadeem Khan, was booked in November 2024 on charges of “promoting enmity” and “criminal conspiracy”.

The FIR accused him of “organising an exhibition on a public platform, creating a museum…putting up photos of well-known public personalities, making allegations, and portraying a particular community as oppressed can incite people and promote separatist activities”.

The exhibition highlighted recent hate crimes and the Supreme Court’s judgments on mob violence.

Beaten In Jail

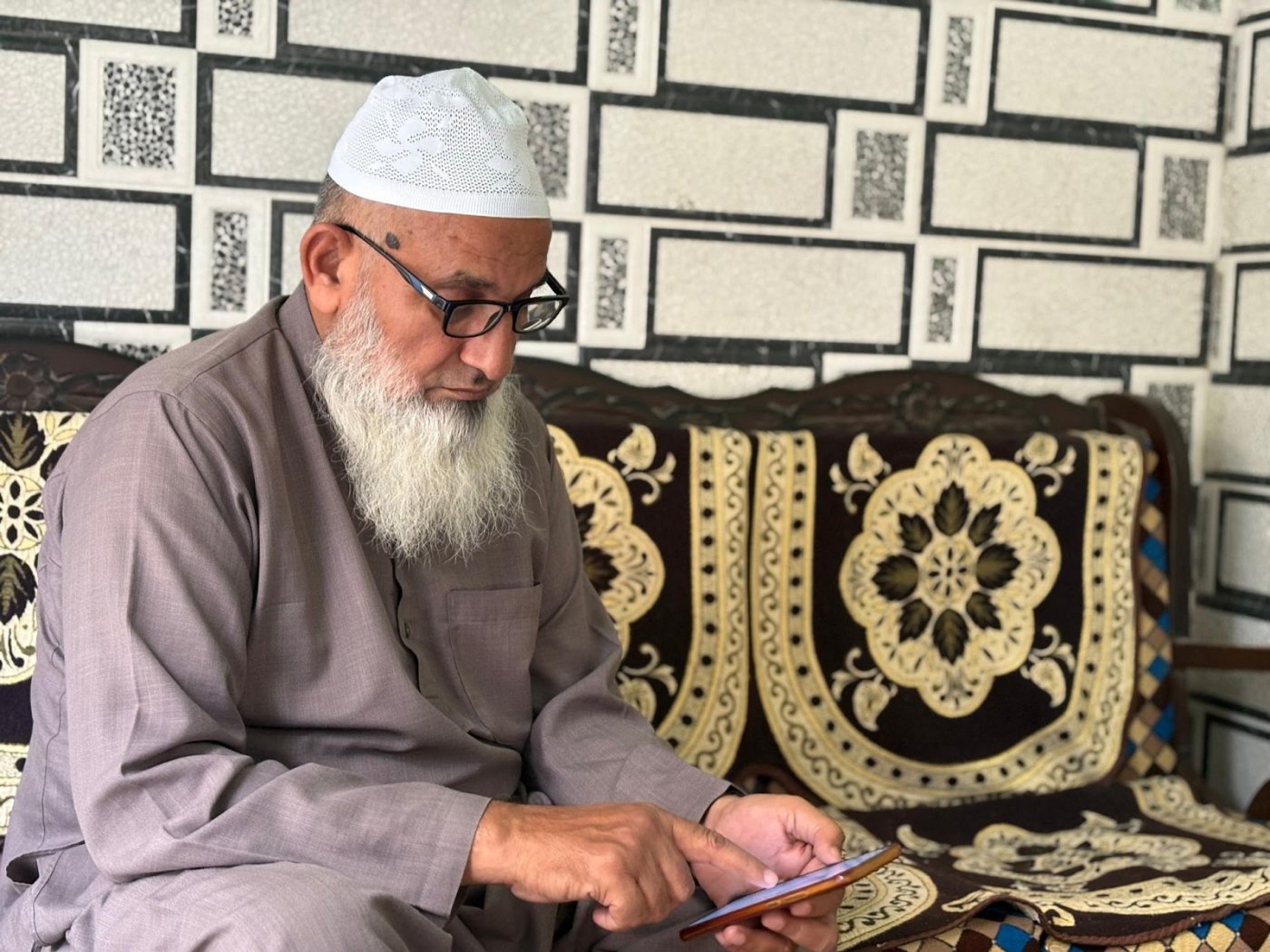

Hashim Ali, 58, has lived in Shiv Vihar with his family since 1992.

Ali said though he has been living in the area for 32 years and never had any enemies, the case has impacted his relationship with his Hindu neighbours.

“If this fire hadn’t happened, we’d still be as close as before, but now the false case has damaged our bonds,” said Ali.

Ali lost his clothing export business to the riot.

“In 2020, we had our own business, but the losses from these riots set us so far back that now we’re forced to work for others,” said Ali. “We’ve reached the edge of ruin.”

Ali said his shop, which had machines for making hosiery shirts, was looted by rioters. “Everything was looted, causing us a financial loss in Lakhs.”

Ali said that in addition to losing his business, three motorcycles and a three-wheeler he owned were also burned during the riot.

Despite being a victim of the riot, Ali was arrested on 4 April and spent a month and a half in jail: first in Tihar Jail, then Mandoli Jail.

Ali said he was mistreated in jail.

“In Tihar, Muslims were pulled out and beaten,” said Ali. “I was beaten without reason; even my beard was disrespected. The inmates handing out food hit me while the police stood by and watched.”

Article 14 contacted the public relations officer of Delhi prisons and the director general of Tihar jail on 20 December, seeking comment via email. There was no response.

This story will be updated should they respond.

In 2021, Rashid Zafar, an undertrial prisoner, claimed that he was beaten in Tihar jail and forced to chant 'Jai Shri Ram'.

Zafar had been charged with being a part of an Islamic State-inspired group that was planning suicide attacks and serial blasts against politicians and government buildings in Delhi and other parts of North India.

In April 2019, another Muslim undertrial named Shabbir alleged that he was beaten and branded with an 'Om' symbol by a jail superintendent after raising concerns about malfunctioning equipment.

Culprits Remain Free

Ali was in charge of Madina Mosque, next to Naresh Chand’s house. Naresh Chand later filed an FIR naming Ali among the men who set his house on fire.

“We don’t know how the fire started there; we swear by God that we weren’t involved, but still, our names were mentioned,” said Ali.

Ali said he filed a complaint against 15 individuals whom he recognised as culprits for setting fire to his home and the mosque. He said no action has been taken to date against them.

Ali said his main grievance is that despite being innocent, he was sent to jail at the age of 58, while those who caused the destruction remain free.

Ali said that the case was his first experience of the legal system.

“My ancestors had never seen the inside of a court. It was also the first FIR against my son, Rashid Ali,” said Hashim Ali. “We pray to God that such riots never happen again. We don’t want our children to witness what we’ve endured. We were forced to survive on the charity of others.”

Over the past four and a half years, fighting this case has cost them money and brought tremendous financial trouble to his family. “Between my son Rashid Ali and me, we’ve spent around 5-6 lakhs on this case,” he said.

Ali said he no longer works after his clothing export shop, his only source of income, was burnt down.

“I just sit and pray in the neighbourhood,” said Ali. “My only purpose now is to seek justice for the mosque and my home, that those responsible be held accountable.”

(Aqib Nazir is a freelance journalist who writes on environment, politics and human rights issues. Adnan Ali is a Delhi-based freelance journalist who writes on minority issues and human rights. Huda Ayisha is a Delhi-based freelance journalist who writes on minority issues, human rights violation and civic matters.)

Get exclusive access to new databases, expert analyses, weekly newsletters, book excerpts and new ideas on democracy, law and society in India. Subscribe to Article 14.