New Delhi: It is not as though bulldozers—large motorised trawlers with metal blades in front that can both carry construction materials and destroy homes—are recent entrants into India’s governance landscape, nor have they only now been co-opted as emblems of decisive governance.

For decades, the bulldozer has been an abiding source of trepidation and fear for city dwellers living in informal settlements or vending on street pavements. Those living in slum and pavement homes or street vendors are forced to live and work in a zone of enduring illegality because of exclusionary city management policies and plans.

Too often, with little or no notice and no alternative living and work arrangements, the bulldozers arrive and destroy in minutes their entire life savings. Many court rulings over the years (here, here and here) have prescribed a more humane process of giving sufficient notice to the resident or vendor of the shanty or pavement, and the establishment of viable survival alternatives.

These orders are rarely obeyed in spirit, or even in letter. The more fundamental problem with this vintage form of bulldozer “justice” is that these have done nothing to reverse the profound inequities of city planning that exclude the working poor from lawful inclusion.

We are seeing in recent years in India, under the stewardship of Prime Minister Narendra Modi, a massive rise in demolitions. The Housing and Land Rights Network (HLRN), a legal advocacy group, reported a rising trend of evictions between 2017 to 2023, with over 1.68 million people affected.

The number of evictions across India has steadily risen from 107,625 in 2019 to 222,686 in 2022 to 515,752 in 2023—in other words, a 379% increase over five years. The data also reveal that 89% of those whose homes were demolished over 2022 and 2023 were either Muslim, scheduled tribe, scheduled caste or other backward class.

Escalating Cruelty & New Targets

As in the past, the reasons given by the state for forced evictions range from plans for smart city initiatives, road expansions, highways and infrastructure and forest protection, and sometimes more vaguely just “clearing encroachments” or “city beautification”.

This period is also marked by even greater needless gratuitous cruelty than we have seen in the past. These were some of the voices in a 2024 story on “India’s Bulldozer Raj” in the magazine Frontline:

- Sheikh Akbar Ali: “Earlier, we never saw bulldozers coming after 5 pm or early in the morning, but now that is also common.” Many spoke of massive contingents of paramilitary forces deployed during demolitions.

- Ashok from Delhi: “They are not just trying to remove us from this site but ensuring that the place is no longer habitable. Where will we go from here? The last time they came to demolish our jhuggis, they dug a pit 5-6 feet deep so that we could not rebuild our houses at the site”.

- Rekha, a farmer on the Yamuna floodplains: “They have attempted to displace us multiple times. They dig pits and throw our essential belongings, including basic necessities like rations, into them before filling them with sand.”

- An unnamed woman in Delhi: “We weren’t even given time to retrieve our valuables and belongings. My children’s books and uniforms were all gone. It was raining heavily on the day of the demolition. We pleaded with them to at least grant us one day to salvage our belongings. However, with our houses, our dreams also crumbled.”

In 2023, Article 14 reported how, despite established law requiring prior notice before demolitions and rehabilitation of those affected, at least 1,600 homes were demolished, and about 260,000 people were homeless in India’s capital, after four major demolitions over three months, with notices often served as demolition squads moved in.

On 24 February 2023, Prime Minister Narendra Modi asked finance heads of the G-20 group of countries to focus on helping the “most vulnerable”, even as his government demolished homes of some of Delhi’s poorest, including those in government-run homeless shelters, some of which were razed as well.

In a basti or slum adjacent to Delhi’s medieval Tughlakabad fort, demolitions continued into the night amid heavy rain, with affected residents complaining about the use of harsh police force. Bipasha Mandal, a domestic worker in her twenties, said a female officer pulled her hair as bulldozers tore down her home.

Bulldozer ‘Justice’ Over Courts

Anand Lakhan, a housing rights activist from Madhya Pradesh, spoke to Frontline of his despair in the possibilities of justice after the manifest retreat of the courts from their more active role in the past to secure justice for people threatened by demolitions.

“From court’s justice we have moved into times of bulldozer justice,” said Lakhan. “Initially, we believed that we could rely on presenting solid evidence in court rather than appealing for mercy. However, the government often disregards this evidence entirely.”

In sending out bulldozers, state authorities are untrammelled by the imperatives of constitutional rights and the rule of law. There is, after all, no law in any Indian statute book that empowers the state to destroy the properties of a person simply for committing a crime.

Justice A P Shah, former Chief Justice of the Delhi High Court, said that “(m)ere involvement in criminal activity cannot ever be grounds for demolition of property”.

To conclude that a person has actually committed a crime, the Constitution and law establish an elaborate procedure protecting the rights of the accused person before a person is punished. This, too, is now casually being thrust aside.

As a highly regarded retired judge of the Supreme Court, Madan Lokur, asked: “Under what provision can (the administration) demolish their house for an offence which hasn’t been proved?”

This destruction of homes has recurred over the past many decades in the Indian republic (here and here). But what has changed in this new era of the bulldozer is the targets and ideological deployment of the bulldozer for exclusionary hate politics.

Selective, Performative Demolitions

For the record, municipal and district officials mostly continue to claim that bulldozers are rolled in to destroy homes only in routine drives against unlawful encroachments. They do not explain why only some properties are targeted while hundreds of others in the vicinity with the same contested legality are untouched.

In 2025, in Ujjain and Damoh in Madhya Pradesh—governed by the BJP—Muslim suspects were publicly shamed, flogged, paraded and forced to chant slogans like “cow is our mother” and “police are our father”. The acceptance of such shaming even led to political competition in humiliation. In Damoh, the municipal council, run by the Congress party, ordered their properties demolished, while in Chhindwara, in the same state, Hindu suspects in a recent cow slaughter case were arrested without a public spectacle or much media coverage.

Hiding as they do behind back-dated notices, they also do not explain the suddenness of the demolitions, why these often immediately followed by communal skirmishes or protests by Muslims or, sometimes, an imaginary slight.

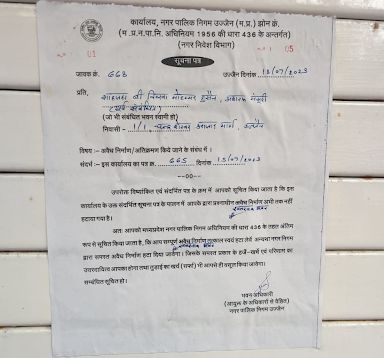

For instance, as Article 14 reported in 2023, on the basis of allegations with no evidence, police in the Madhya Pradesh city of Ujjain arrested three Muslim teenagers accused of spitting on a Hindu procession. Accompanied by drummers and music, municipal officials then demolished their home, claiming the building was ‘dangerous’.

Two former police chiefs, a high court judge and a Supreme Court lawyer said the Ujjain demolition was illegal and unconstitutional. The scared, anxious family could only think of getting their children out of jail.

But political leaders were mostly much more candid. They gloat that they sent out bulldozers to extend exemplary and immediate punishment to wrong-doers, dog-whistling against the Muslim targets of the demolitions.

The pattern of many demolitions is for Hindu religious processions to stop outside mosques, with men dancing feverishly to blaring loud music, H-Pop, or Hindutva pop, songs that insult and abuse Muslims, their Prophet and their faith. This typically sparks off a communal skirmish. After only a day or two, bulldozers arrive to raze the properties of men who the police and local administration deem to be responsible for violence. Hindu instigators and participants in the violence are never so punished.

Another frequent situation is when Muslims take to the streets to protest either public insults to the Prophet or their public worship or the demolition of mosques or mazaars (shrines). Bulldozers are deployed to lay waste the homes of persons whom the police and administration regard as leaders and participants in the protests.

In these hasty performative demolitions, sometimes demolished properties are not even built or owned by the persons the state wished to target.

Violations Of Natural Justice

In one instance, the local administration claimed that they had reason to believe that the man they sought to punish had invested partly in the home they peremptorily tore down. In another, in Ujjain, the house of a schoolboy who had stabbed to death his classmate was razed.

Each of these state actions unapologetically and defiantly violated all established principles of natural justice. No law in India’s statute books empowers the state to demolish the properties of a person guilty of a crime. And to establish that a person is indeed culpable, the burden vests with the state to collect evidence of the person’s guilt and to present this in a court of law.

Even if the trial court finds a person guilty, they have the chance to appeal to the high court and then the Supreme Court. If found guilty by courts at all these levels, a person can be punished, but only in ways that are prescribed in the statutes.

Apart from all of this, the State is constitutionally barred from targeting and discriminating between citizens on grounds of their religious identity. Bulldozers in states run by the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) have metamorphosed into weapons of State assault on a segment of the country’s citizens.

With rarely even a pretence to due legal process, let alone constitutional fairness, successive state governments in several BJP-ruled states after 2019 have targeted mostly Muslim citizens.

The atmosphere is typically festive as properties are demolished, often as onlookers and television media cheer, and elected leaders of government and the ruling party hail the demolitions as acts of brave and righteous retribution, a form of muscular and celebratory extrajudicial punishment without establishing guilt.

In doing so, BJP governments have crossed a red line, signalling to the citizenry, the political opposition and the courts their rejection both of constitutional governance and secular democracy. In pursuit of their open hostility against a section of their citizens, the State has become defiantly lawless.

This newer trend reflects a clear rise in recent years in punitive demolitions targeting mainly Muslims.

Muslims Are The Target

Frontline reported, for instance, in 2023 several cases of evictions and demolitions in Madhya Pradesh’s Khargone, Prayagraj, Saharanpur in Uttar Pradesh; Nuh in Haryana; and Jahangirpuri in Delhi, among others. Article 14 has routinely tracked these and other demolitions, such as one of the largest in Gujarat in August 2025.

In the name of national security, more than 12,500 homes around Ahmedabad’s Chandola Lake were demolished in 2025 after a crackdown on “illegal Bangladeshis”, Article 14 reported, leaving thousands of Muslims—many were Indian citizens with valid documents—homeless. Homes were razed without notice, belongings were buried under debris, and children were pulled out of school.

While the Gujarat government claimed the operation was aimed at illegal immigrants, the demolitions, detentions, and quiet deportations—mostly affecting Bengali-speaking Muslims—revealed flimsy verification, discriminatory housing laws, and a growing climate of fear.

Demolitions often target specific groups. For instance, after communal clashes during a Hanuman Jayanti procession on 20 April 2022, municipal officials with 12 companies of a paramilitary force demolished 25 shops, vending carts, and houses primarily belonging to Muslims in Jahangirpuri.

The same happened in Khargone, again after communal violence during Ram Navami and Hanuman Jayanti celebrations in April 2022, when 16 houses and 29 shops belonging to Muslims were demolished.

An Amnesty International report of February 2024 said that Muslims were targeted in 128 demolitions that affected 617 people.

Properties that were demolished included homes, businesses and places of worship, largely of Muslims in the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP)-ruled states of Assam, Gujarat, Madhya Pradesh, and Uttar Pradesh, and the Aam Aadmi Party (AAP) governed state of Delhi.

The report documents that house demolitions were largely carried out in Muslim-majority areas, specifically targeting properties owned by Muslims even in mixed neighbourhoods. Hindu-owned properties nearby—particularly in states like Gujarat and Madhya Pradesh—were left untouched.

The communities most affected were those that had recently experienced high levels of Hindu–Muslim violence, often following provocations by Hindu groups during Ramzan, or where Muslims had held protests.

HLRN data reveal that Muslims constituted 44% of more than 700,000 people evicted over 2022 and 2023: 23% were scheduled tribes, Adivasi and other tribal groups; 17% were other backward classes; and 5% were scheduled castes.

Such selective demolitions were also evident in Assam in 2024, as the Supreme Court served a contempt notice to the Assam government for demolishing homes—on land set aside for tribals—ignoring a 17 September 2024 order putting demolitions nationwide on hold.

Villagers, activists, and lawyers argued that the eviction of mostly Bengali-speaking Muslims in Assam violated judicial precedents about how to remove people from public or protected land. Hindu homes on the same land were not touched. Article 14 reportage found some had land titles from the 1920s, before the land was designated tribal land.

‘Tool Of Collective Punishment’

Amnesty International’s secretary general, Agnes Callamard, condemned demolitions as “cruel and appalling,”—unlawful, discriminatory, and a form of unjust displacement.

As Frontline noted, demolitions have become “a tool for collective punishment, reinforcing communal fault lines rather than addressing legal or administrative concerns. While evictions often follow patterns that appear distinctly communal and punitive, the legal process remains narrowly focused on procedural legitimacy”.

Many of the affected houses do fall into grey areas of legality, much like the homes of poor people across castes and religions throughout the country. However, the alleged illegality of Muslim-owned properties, many noted, is selectively weaponised to justify demolition.

Demolitions often followed claims of Muslim-led violence, even though RSS-affiliated groups provoked many clashes. Routes of Wrath, a 2023 report edited by Supreme Court lawyer Chander Uday Singh, showed how, during Ram Navami 2022, processions were repeatedly steered toward mosques, where loud music and abusive slogans sparked minor skirmishes. Soon after, especially in BJP-ruled states, bulldozers arrived to destroy the homes of Muslims labelled as rioters.

Similar punitive demolitions followed Muslim protests—such as in Prayagraj after demonstrations against BJP spokesperson Nupur Sharma—or served as ad hoc punishments, as in Ujjain in 2023. In Assam, Bengali Muslims are widely targeted as alleged “infiltrators.”

Major newspapers, including The Indian Express, The Times of India, and The New Indian Express, described these actions as unlawful, punitive, and contrary to constitutional norms.

The Indian Express said in June 2022 that “in a constitutional democracy, the bulldozer on a rampage is the state thumbing its nose at the court, the DM and SP playing judge and jury—and loyal executioners”. It added that when UP officials and politicians “boast about ‘Saturdays’ following ‘Fridays’, and ‘return gifts’ to the riot-accused, (this) marks a new level of brutalisation in public discourse”.

‘Dark Carnival’

Scholars and rights advocates argue that the demolitions instil fear and reinforce Muslims’ second-class status. The bulldozer has meanwhile become a celebrated symbol in North India—featured at BJP rallies, in pop music, on T-shirts and tattoos, and even in an Independence Day parade in New Jersey, which drew strong protests and condemnation by U.S. senators.

In 2022, UN special rapporteurs warned that these “forced evictions and arbitrary home demolitions” were punitive measures violating international human rights standards. Anthropologist Thomas Blom Hansen sees the bulldozer as a “revenge” symbol and a tool of State power deployed with partisan impunity.

Witnesses describe many demolitions as public spectacles that echo earlier histories, as in Jim Crow America—an era of widespread legal racial segregation and discrimination against African Americans, primarily in the southern US, lasting roughly from the late 1870s until the mid-1960s—in which crowds celebrated the humiliation and murders of minorities.

Hansen views India’s bulldozer ‘justice’ as a marker of “a new phase in the Hindu nationalist project”. Hindus, he says, believe that Hindus have suffered for centuries under Muslim rulers, portrayed as uniformly oppressive and bigoted. The bulldozer is celebrated, he adds, as “a form of payback, a revenge fantasy” for these perceived injustices.

Second of a six-part series.

(Harsh Mander is a peace and justice worker and writer. Omair Khan provided research support. This work was supported by Diaspora In Action for Democracy and Human Rights.)

Get exclusive access to new databases, expert analyses, weekly newsletters, book excerpts and new ideas on democracy, law and society in India. Subscribe to Article 14.