Jammu: Girls and boys aged about 10 to 12 years, nylon sacks hoisted over a shoulder, wandered through the narrow lanes in the Kiryani Talab locality of Narwal, a commercial hub in Jammu. They trawled the street corners for anything of value in piles of garbage—tin cans, plastic bottles, the occasional cardboard carton.

At the 20 or 30 shops built of wooden planks and tin sheets standing along these lanes, children aged eight to fifteen years worked alongside a parent or guardian, selling vegetables, fruit, and dried fish, or offering mechanical repairs or barber services.

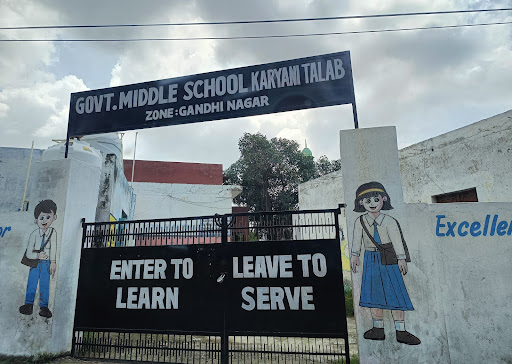

Alongside a mosque, the voices of teachers and the recitation of lessons in chorus drifted out from the Government Middle School, Kiryani Talab. For the estimated 3,000 Rohingya children who live in a slum colony in this area, however, school has remained a dream. The school authorities have refused to admit them on account of not being Indian citizens.

Mohammad Arif, in his thirties, a parent and community leader, runs a small shop with plastic jars full of toffees lining the counter, a small fridge in a corner, and shelves holding a few bars of soap, packets of biscuits, and washing powder.

“I just came from the directorate of school education,” Arif said, sighing. “It was my second visit—but all in vain. The officer wasn’t there.”

Rohingya children wash their hands and feet at a public tap after spending hours collecting trash. The tap is located near their makeshift tents in the Kiryani Talab area of Narwal, Jammu/ BASHARAT AMIN

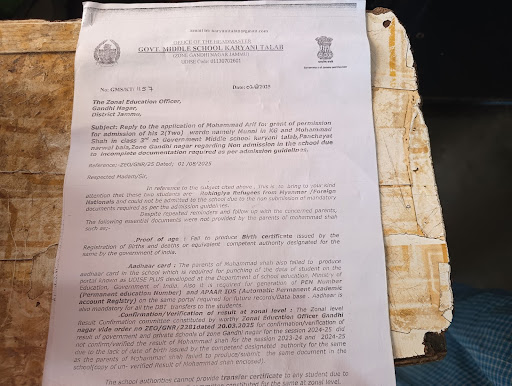

In July 2025, Arif filed an application at the zonal education office in Gandhi Nagar, Jammu, seeking an explanation for the denial of admission to his two children.

In a written reply dated 2 August 2025, the office said: “The parent of Muni and Mohammad Shah, who sought admission in Class KG and Class 3 respectively, has failed to submit the following essential documents: proof of age (birth certificate), Aadhaar card, PEN (Permanent Education Number), and APAAR ID (Automatic Permanent Academic Account Registry).” The letter instructed Arif to approach the chief education officer or the directorate of school education.

“Should Our Kids Become Trash Collectors?”

Arif’s son Mohammad Shah, 12, who helps out at the store, has not been to school since the 2023-2024 academic year. His hair neatly trimmed, the boy weighed and bagged potatoes for a customer as his father spoke. He has a sister, Muni, 8, who has also been out of school since 2023.

In 2020, his admission was processed after authorities asked him to submit an affidavit with his name, place of origin and date of birth, duly signed by district magistrate. An average student, he completed Class 3 before being made to drop out in the 2023-24 academic year.

“When our children are denied education, they wander from lane to lane, slip into other’s houses, and bring home anything they think can be reused,” said Arif. “What does the government want? That our children become trash collectors?”

According to Development And Justice Initiative (DAJI), a non-profit organisation registered in Delhi, Jammu was home to about 5,700 Rohingya refugees in the year 2017, many having lived there since the early 2000s. Unofficially, local authorities say the number of Rohingya refugees in Jammu is now closer to 10,000.

Having fled religious and ethnic persecution in Myanmar, the refugees in Kiryani Talab told Article 14 that they crossed into Bangladesh and stayed there a few nights. Later, men who said they were guides asked them to board a bus, promising to take them to a safe destination for a fee of Rs 10,000 each. They were dropped at the border of West Bengal and found their way to Kolkata, from where they boarded a train for Jammu, they said.

Their living conditions and livelihood challenges have been the subject of scrutiny in recent months by United Nations representatives and chief minister Omar Abdullah.

Like most Rohingya families living in Narwal, Arif and his children possess identification cards issued by the UNHCR, the United Nations’ refugee agency. Their dates of birth are mentioned on the cards.

For Rohingya children in Jammu, the locked school gate is more than a local bureaucratic hurdle—it is part of a global pattern. Worldwide, nearly half of all refugee children are denied schooling, according to the UNHCR. Of the 31.6 million refugees under its mandate, approximately 14.8 million are children, who suffer severely limited access to education. In 2022-23, the average enrolment rate for these children was only 37%.

In India, from Delhi to Hyderabad to Mewat in Haryana, Rohingya families have recounted similar struggles to access amenities including schooling. Despite legal safeguards and court orders, Rohingya refugee children in India join this lost generation that grows up without classrooms or books.

While schools in Jammu previously permitted Rohingya students on the basis of sworn affidavits signed by the district magistrate, in recent years authorities have begun to insist on government documents.

Arif pointed to Supreme Court of India directions (see here) to ensure that children faced no discrimination in accessing education. “Prime minister Narendra Modi often uses the phrase ‘Beti Bachao, Beti Padhao’ (save the girl child, educate the girl child),” he said. “Is there any difference between my daughter and other girls?”

Article 14 contacted Jammu’s director of school education Naseem Javed Choudary for a comment on the denial of admission to Rohingya children despite SC orders directing otherwise. Despite repeated calls, he remained unavailable.

Court Orders To Admit Rohingya

In February 2025, the Rohingya Human Rights Initiative, an NGO working for the rights of Rohingya refugees, filed a petition in the Supreme Court through lawyers Colin Gonsalves and Manik Gupta, seeking directions to the government of India and the Delhi state government to grant Rohingya refugees in the capital city access to public schools and hospitals.

In February 28, 2025, granting interim relief, the Supreme Court said all Rohingya children should be granted admission to educational institutions, “free of cost, whether or not the family has an Aadhaar card”. It said these children should be allowed to sit for examinations including Class X and Class XII board exams and graduation, “without the government insisting on the Aadhaar card”.

Delhi-based Supreme Court lawyer Ujjaini Chatterji told Article 14 that all children, whether citizens or non-citizens, while within the territory of India, are entitled to the right to education, which falls within their right to life and personal liberty under Article 21 of the Constitution of India. “This has been repeatedly clarified by the Supreme Court of India, and more recently in two orders that specifically granted the right to education to Rohingya children living in India,” she said.

Chatterji said that under the National Education Policy (NEP) of 2020 and the Right to Education Act (RTE), 2009, all children aged 6–14 years are guaranteed free and compulsory schooling, regardless of citizenship, making the denial of admission to Rohingya children a breach of the law as well as Articles 14 (right to equality before the law), 21 (right to life and liberty) and 21 A (right to education) of the Constitution. The RTE Act imposes no citizenship requirement, she said.

“Families whose children are refused admission can petition education authorities, approach the national or state commissions for protection of child rights, or move high courts under Article 226 (right of high courts to issue certain writs) to compel admission,” she said, adding that beyond domestic laws, India is also bound by international obligations under the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights, the Convention on the Rights of the Child, and the Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Racial Discrimination, all of which guarantee education for every child without discrimination, “making such denial a clear violation of its commitments”.

John Quinley, director of Fortify Rights, a Bangkok-based human rights organisation that works with Rohingya communities across Malaysia, Indonesia, Bangladesh, Thailand, and India, said several courts in India, including lower and upper courts, have held denial of education to be unconstitutional. “A number of Indian lawyers have explained to the courts how such denial violates constitutional guarantees, and that Rohingya children also have the right to formal education,” he said.

The impact of the denial of admission to Rohingya children would be “huge and generational”, he said. He described Rohingya children as genocide survivors and argued that preventing them from accessing education aids a wider project to erase their language, culture, and identity. “India is not responsible for the genocide, but it is responsible for extensive discrimination by not allowing Rohingya children into schools,” he said.

The policy to prevent them from accessing education is repressive, and amounts to a form of persecution, he said.

Only 6 Rohingya Children Passed Class XII

State education departments as well as the government of India should issue clear guidelines and adopt a different approach on admitting Rohingya children, said Quinley.

He recommended that local governments work with the UNHCR and other service providers to ensure educational opportunities for refugee children, including access to books, uniforms, and stationery, noting that refugees already face severe challenges in securing livelihoods.

“If the government penalises local administrations or teachers for admitting these children, it is highly irresponsible behaviour,” he said.

India, however, is not a signatory to the Refugee Convention of 1951, which provides the internationally recognised definition of a refugee and outlines the legal protection, rights and assistance a refugee is entitled to receive.

Even so, India is bound by international norms, Quinley said. “Denying Rohingya children an education is a clear breach of those obligations.”

In Jammu, only six Rohingya children have passed Class XII—Mustafa, Sajid, Shamiya Janat, Jaisheen, Mohammad Amin and Mohammad Javed Mir.

“We were not allowed to study further,” said Mohammad Javed, 20, who completed Class XII from Government Model School Sujwan, Jammu, in 2023. Higher education was not possible without the documents the government was seeking, he said.

Javed now runs a community learning center in Kiryani Talab. The center is housed in a tin shed, and 300 students attend English, math, science, Urdu and political science classes in four shifts.

They had no other option but to improvise, according to Javed. “We don’t want our community’s children to remain illiterate,” he said. “Our children are different from local children in terms of struggle—they live in unhygienic and harsh conditions, enduring rain and extreme heat in tents. Despite this, our children still want to be educated.”

According to a survey conducted last year by community volunteers, 3,000 Rohingya children in Narwal are eligible to go to school, but fewer than 200 are receiving formal education because they were enrolled before the implementation of the NEP. “After that, no one was permitted to be admitted,” said Javed.

‘Serious Inter-generational Effects’

At the learning center, 19-year-old Noor Zuha, dressed in a blue T-shirt, sat with a pile of books. Asked about his ambitions, Noor paused before answering, “First, I want to become a good human being.” What defines a good human being? “Someone who recognises the pain of others,” he said.

Noor said Rohingya people in Jammu were easily scammed and manipulated by fake news. He said he hopes to change that.

Vijay Raghavan, professor at the Centre for Criminology and Justice, School of Social Work at the Tata Institute of Social Science (TISS), Mumbai, said a child's overall progress is often shaped by education, and the learning imparted by teachers is not easily gained on their own.

Project director of Prayas, a field action project working with prisoners and their children left outside, Raghavan said, “Dropping out from school can have intergenerational effects, weakening one of the most important institutional support mechanisms for developing responsible citizens.

By denying children the opportunity to education, it could lead to some children getting drawn or pushed into delinquency—drifting into bad company, adopting negative lifestyles, substance abuse, petty crimes, or become victims of exploitation by adults, or even sexual abuse.”

Community learning centres and other community support do help in reducing these risks, he said. He cited the example of a TISS field action project named TANDA (Towards Advocacy, Networking and Developmental Action) that works with nomadic communities and their children. The project appoints local teachers who can better understand children’s needs and preserve their cultural identity.

The Dying Hope Of A Schooling

Aged 20, Noor Kamal was seated in a Class VIII classroom, not of a school, but in the modest community learning center run by Javed. For years, his refugee status kept him from enrolling in formal education, leaving him to learn on his own.

“I’ve always dreamed of studying in a real school,” Noor said, his voice reflecting his longing. “I want to feel the atmosphere of a classroom—teachers teaching, students learning together—but I had no choice but to take up self-study.”

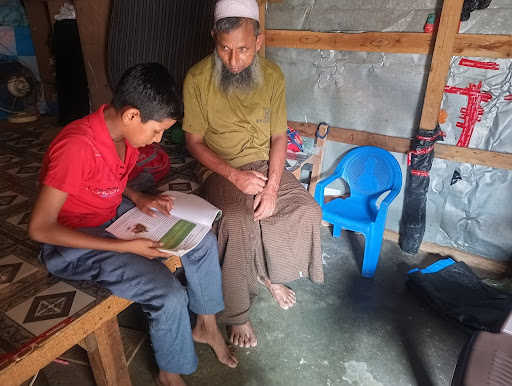

Fourteen-year-old Najeeb, holding a book, sat on a wooden platform in a dusty, poorly lit shed-like room beside his father, Mohammad Alam. As he recited a few lines from an English book, a faint light flickered in his father’s eyes.

“I am both grateful and disheartened,” Alam said quietly. “My child is enrolled in a nearby government middle school, but many other children in our community have been denied admission.”

He said as refugees their lives were full of hardship, and it was the possibility of an education that held out hope. “Now,” he added, “it feels like even that hope may be short-lived.”

(Basharat Amin is a multimedia freelance journalist based in Jammu and Kashmir.)

Get exclusive access to new databases, expert analyses, weekly newsletters, book excerpts and new ideas on democracy, law and society in India. Subscribe to Article 14.