Sopore, Baramulla (Jammu and Kashmir): On 14 March 2020, Nisar Ahmed Ganaie, 33, the lone bread-winner for his family, left home at noon, walking towards the busy Sopore market where he ran a confectionary shop.

He was to have returned home later that evening. Instead, a neighbour in the market told the family that Ahmed had been picked up by the police.

The family contacted the local police station the next day, but without any information on his arrest, hoped that Ahmed would be released soon.

It was on 23 March that the family found out he had been arrested under the Arms Act, 1959, in a case pertaining to the illegal delivery of arms. A press release issued on 23 March by the Sopore police said Ahmed was among four men arrested the previous day from near the district hospital. Accompanying the press release were photographs of eight assault rifles, magazines, and other ammunition.

Mohammed Akbar Ganaie, 64, Ahmed’s father, said his son's arrest had shocked the family.

“Nisar Ahmed is my lasting hope in this old age,” he said. Detained after police allegedly recovered arms from him, Ahmed was first kept in Baramulla sub-jail, said the family.

He remained there for about a year before being moved to Haryana’s Gurgaon district jail, more than 900 km south of his home in Pathipora Krankshivan, a colony in Sopore city. Since 2021, Ahmed has remained in the Gurgaon jail.

According to the family, at the time of the arrest, they were not aware of the charges against Ahmed. A few weeks later, they learned that he had been booked under the Unlawful Activities Prevention Act (UAPA), 1967.

The Sopore police issued a press note that said Ahmed had been booked under section 7 (prohibition of acquisition, possession, manufacture, sale of prohibited arms and ammunition) read with section 25 (punishment for offences) of the Arms Act, 1959, and sections 18 (punishment for conspiracy), 20 (punishment for being a member of a terrorist organization) and 23 (enhanced penalties) of the UAPA.

Since Ahmed was moved to Gurgaon, the family has been unable to visit him. Akbar said they could not afford to make trips to Haryana and had requested officials to permit a video call with Ahmed.

“It has been more than eight months now that we have not seen him,” said Akbar. “We don't know whether he is alive or dead.”

Ahmed is among hundreds of Kashmiris being held in prisons outside the union territory of Jammu and Kashmir. Since the revocation of Kashmir’s special status on 5 August 2019, as many as 343 persons accused of crimes in the union territory have languished in jails outside Jammu and Kashmir. These include politicians, businessmen, those accused of being stone-throwers, and other alleged criminals. Most of these persons are in jails in Uttar Pradesh (UP) and Haryana.

In May 2021, prompted by concerns for their health during the Covid-19 pandemic, the Jammu and Kashmir high court bar association sought that these prisoners be shifted back to jails in Kashmir.

Officials view prisons in Jammu and Kashmir as breeding grounds for extremism, and moving Kashmiri prisoners to outside jails is part of a security strategy to stop the radicalization of alleged criminals. Prisons have been misused to spread militant activities through phones and social media, some reports have said.

On 29 April 2023, the Jammu and Kashmir and Ladakh high court said only a magistrate or court had the authority to move a prisoner awaiting trial from one jail to another. Live Law reported that after a detenu was remanded to a certain prison, only a court or judge could authorise a transfer.

Advocate Irfan Hafeez Lone, the counsel for Nisar Ahmed, said that the ministry of home affairs could order a prisoner to be moved.

“The matter of concern is that their trials are delayed in courts due to several reasons,” said Lone.

Another Srinagar-based lawyer speaking anonymously told Article 14 that preparing a defence strategy becomes difficult in cases where the accused is shifted out of the union territory, amid clients’ fears that their privacy is compromised during phone calls to lawyers.

Why Prisoners Are Transferred Out Of Kashmir

Since October 2022, there have been at least 29 targeted attacks in Kashmir resulting in civilian casualties. Since then, the police have arrested more than 800 persons believed to be what they call "overground workers" or OGWs, people believed by security agencies to provide logistical and other support to militants, or who were previously known to have links to terrorism aided by Pakistan.

To stop militant activities inside prisons in Jammu and Kashmir, security agencies took the decision that hardcore militants and criminals would not be allowed to stay in one jail for long, to prevent the possibility of their networks being strengthened with the help of criminals lodged in their barracks.

In September 2022, the then director general of police for prisons, H K Lohia, had said that moving prisoners from Jammu and Kashmir to prisons in other states was an “administrative exercise” undertaken because of overcrowding of jails.

In 2021, reports said 4,572 inmates were lodged in the union territory's jails, which had a capacity of 3,426.

On 12 June 2023, at the Jashn-e-Dal festival organised by the J&K Police, director general of police Dilbagh Singh was asked by a reporter about Kashmiri political prisoners held in outside jails and if there was any policy for them to be released. Singh said the authorities had a “very clear policy”, and those who violated law and order in the region “won’t be spared”.

In 2022, inspector general of police (IGP) of Kashmir Zone, Vijay Kumar, said OGWs are a challenge for the security agencies. During the year, 150 such persons had been arrested, he said.

He said the OGW network is significant because OGWs may not remain in supporting roles forever, but may also carry out militant activities. “That's why we call them hybrid militants," he said.

Meanwhile, Akbar said that before the arrest, the family had been looking for a bride for Nisar Ahmed. Those plans were now in vain, he said.

Police told the family that Nisar Ahmed had been in contact with a Pakistan-based Lashkar-e-Taiba handler to recruit local youth in terrorist activities.

“Let the courts decide whether my son is an OGW or not,” said Akbar. “But put my son in a Kashmir prison so that I can see him.”

Video Calls To Families Dry Up Amid Trial Delays

Nisar Ahmed’s sister, Tawheeda Akhter, 29, told Article 14 that moving him to Gurgaon was a punishment for his family. “In Baramulla court, they would occasionally show us his face on a video call,” she said.

The family received donations from the local village committee to help fund the legal battle, she added.

Until 2020, jail authorities in Jammu and Kashmir often allowed inmates to communicate with families while in custody. The jail administration also set up a video conferencing facility.

While Akhter could speak to her brother via video call during court appearances a year ago, the delays in his trial meant the family could not see him at all.

On 18 February 2023, Mohammad Akbar Ganaie, along with about 12 families from North Kashmir's Baramulla district, travelled 40 km to stage a protest at Srinagar's press enclave. They demanded the release of their sons lodged in various jails across India.

On Getting Bail, Booked Again, Moved To UP

Sajad Gul, 26, a journalism student of Central University of Kashmir and resident of Bandipora in north Kashmir, tweeted a video of a protest on 3 January 2022.

The previous day, Lashkar-e-Taiba (LeT) commander Salim Parray had been killed in a shootout in Harwan, Srinagar. Following Parray's killing a small protest and sloganeering was witnessed in his hometown Hajin, in north Kashmir.

Gul’s brother Javeed Ahmed told Article 14 that he was taken into custody by soldiers on 5 January at 10 pm. The family later learned that he was in police custody and were informed that a case had been filed against him.

Gul was booked under sections 120 B (party to criminal conspiracy), 153 B (imputations, assertions prejudicial to national integration), and 505 B (intent to cause fear or alarm to the public) of the Indian Penal Code (IPC), 1860.

The J&K Police said Gul was arrested for provoking people to “resort to violence and disturb public peace” by uploading videos depicting sloganeering by women.

After nine days in custody, Gul was granted bail by the Bandipora court on 15 January 2022, but was not released as the administration claimed his name was in another FIR registered in February 2021 under sections 147 (rioting), 148 (rioting, armed with a deadly weapon), 149 (every member of unlawful assembly guilty of an offence committed in prosecution of common object) and 307 (attempt to murder) of the IPC.

“We had made all the arrangements to welcome our brother,” Javeed Ahmed said. On 16 January, Gul was booked under the Public Safety Act 1978, and moved to Kot Bhalwal jail in Jammu, 312 km away.

The Public Safety Act allows the detention of any citizen for up to two years without a trial or charge. It allows for the arrest and detention of people without a warrant, or specific charges, and often for an unspecified period.

Javeed Ahmed said the family rarely talked to Gul on the phone. They wrote to authorities requesting to move him to a nearby prison but received no response.

“Even the trials are delayed for one reason or another,” said Javeed Ahmed. “That is another punishment for families of prisoners.”

After spending around five months in Kot Bhalwal jail, Gul was shifted to Bareilly jail in Uttar Pradesh, where he has been incarcerated for more than 500 days. Facing financial difficulties at home, Gul's mother, in her 50s, has never been able to go to UP to see her son. The brother, a labourer, has been the only family member to have visited him in UP.

“Sajad was like a blooming flower and had just started doing well in his profession,” Javeed Ahmed said. “They shattered his dreams.” It was mentally disturbing to the family that he was lodged in jail more than 1,200 km from home, he said.

Javeed Ahmed said theirs is a “patriotic” family and believed in the judiciary. Alongside journalism, Gul was preparing for the United Public Service Commission exams.

‘Move Him To Kashmir, I Want To See My Son Once’

Among those arrested with Nisar Ahmed of Sopore was Manzoor Ahmed Tantray, 32, a shopkeeper.

Tantray received a phone call on 6 March 2020, around 1 pm. It was a police officer from Baramulla police station on the line. (Ahmed was reportedly picked up on 14 March, while the police press release said he was arrested on 22 March.)

“Manzoor was asked to present himself at Baramulla police station for questioning. We handed Manzoor over to police officials at Baramulla,” said Ishfaq Ahmed, Tantray’s younger brother.

It was several days later, on 22 March, that the family was told the arrest was in a case registered at the Sopore police station, 17 km away. Police then conveyed to Tantray’s family that a hand grenade had been recovered from him.

Nisar Ahmed and Tantray were named in the same first information report, Number 50 of 2020 at Sopore police station.

According to the Sopore police, based on an intelligence input about the delivery of arms and ammunition near the district hospital of Sopore, a special team of policemen and units from 22 Rashtriya Rifles, 179 Central Reserve Police Force (CRPF) and 177 CRPF was constituted.

The police press release said the accused men received one pistol and 12 hand grenades, later recovered by the police. “During preliminary interrogation, they revealed that they are in contact with Pakistan-based LeT handler, who has deputed them for recruiting local youths for terrorist activities in the Sopore area,” the release said.

The police claim that the main purpose of the group was to revive the LeT in Kashmir and to accumulate weaponry to arm newly recruited terrorists. Six men were arrested, and investigation was continuing, the release said.

After spending one month in Baramulla sub-jail, Tantray was shifted to Bhaderwah jail, about 300 km south of his home, in Jammu division’s Doda district. A few months later, he was shifted again, to Jammu's Kot Bhalwal jail, before being moved to Rohtak jail in Haryana, more than 800 km from his home. “He has been incarcerated there since,” said Ishfaq Ahmed.

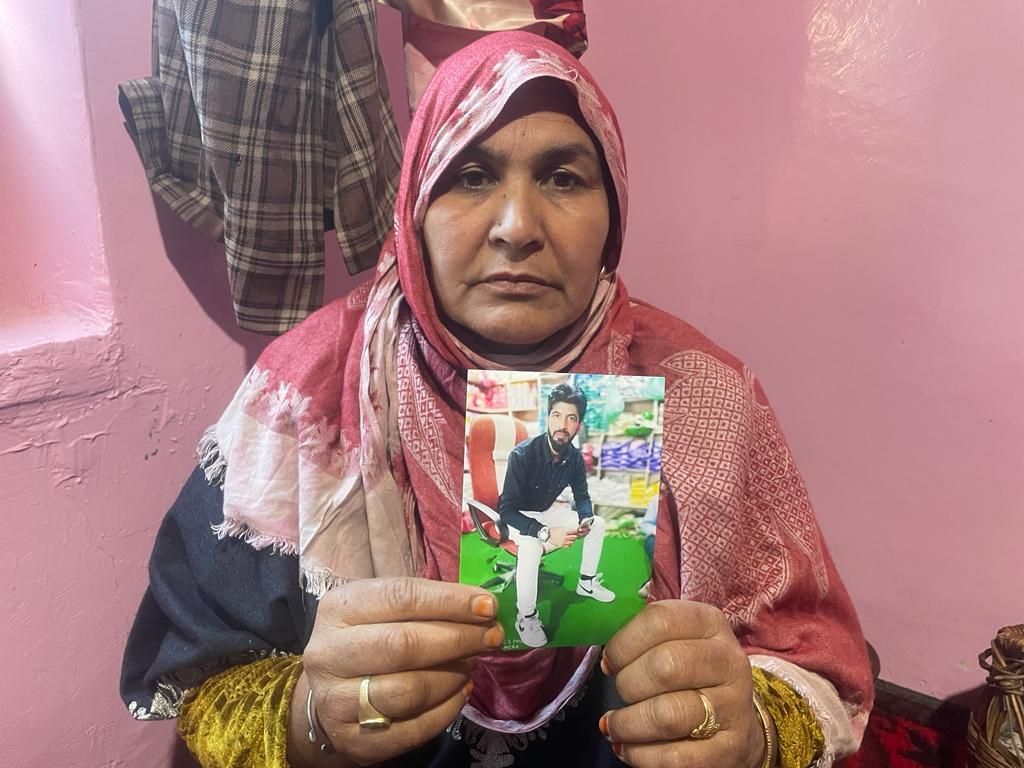

Mehbooba Akhtar, 45, Tantray’s mother, said the family had no money to travel to Rohtak to meet their son, particularly after her husband suffered a brain haemorrhage. “For God's sake, if Manzoor has committed any crime, forgive and release him on humanitarian grounds,” she said.

Tantray ran a grocery shop in Khawaja Bagh, Baramulla. He was married in 2018, and has one child. “Financially, we are going from bad to worse every day,” said Mehbooba Akhtar. “I hope they bring him to a nearby prison in Kashmir, so that I can see him once.”

(Irshad Hussain is an independent journalist based in Srinagar.)

Get exclusive access to new databases, expert analyses, weekly newsletters, book excerpts and new ideas on democracy, law and society in India. Subscribe to Article 14.