Doda, Jammu and Kashmir: On 6 September 2025, a heated confrontation in Doda district of Jammu and Kashmir (J&K) between Aam Aadmi Party (AAP) legislator Mehraj Malik and the deputy commissioner (DC), Harvinder Singh, over the relocation of a health sub-centre escalated into an unprecedented political episode.

The confrontation began when Malik shifted a health sub-centre in Kencha, a small village in Malik's constituency, to a building allegedly owned by one of his supporters. Malik argued that the structure was safer and more accessible for villagers. Officials said the demand amounted to misuse of public resources, as they would be required to pay rent to the owner, unlike in the old building, which the government owned.

Malik reportedly used abusive language against the DC while protesting the health department's failure to pay rent to the villager on whose property he relocated the sub-centre to.

An FIR (first information report) was registered against him at the Gandoh police station for theft of hospital equipment, though he said the health centre’s relocation had public backing.

Within hours of the incident, officials prepared a 33-page dossier against the 37-year-old lawmaker, citing his “habitual confrontation” with officers and his use of social media to “provoke unrest.” The dossier accused him of being a “history sheeter” who had “turned political activism into disorder”, saying he leads villagers into government offices, holds sit-ins, and storms official meetings.

Two days later, on 8 September, Malik was detained under the J&K Public Safety Act (PSA), 1978, a law that allows detention without trial for up to two years. His detention became a new flashpoint in post-abrogation politics, with Mehraj Malik becoming the first sitting legislator in the erstwhile state and now union territory to be booked under preventive detention.

On 24 September 2025, Mehraj Malik filed a habeas corpus petition before the J&K and Ladakh High Court, challenging his detention. The petition described the detention as “punitive, not preventive, rooted in political vendetta rather than legitimate concern.”

Advocate Mujeeb U Rehman, from Anantnag in J&K, who has closely followed the case, said, “The case reflects the tension between administrative authority and civil liberties in Jammu & Kashmir.”

He added that the outcome of Malik’s High Court petition can set an important precedent for how PSA powers are interpreted and exercised, influencing the scope of preventive detention, the protection of personal liberty, and the accountability of authorities in enforcing the law.

As of 30 October 2025, Malik has spent 52 days in detention. He is currently jailed in the Kathua District Jail.

The dossier further accused him of using “social media handles, especially Facebook Live” to launch “verbal and derogatory attacks on anybody who tries to stand up against his illegal demands”.

The arrest has once again sparked concerns about the expanding use of the PSA in J&K, a law long criticised for being invoked against journalists, activists and now, elected politicians. Political leaders across parties warned that Malik’s detention marked a new threshold in the shrinking space for dissent.

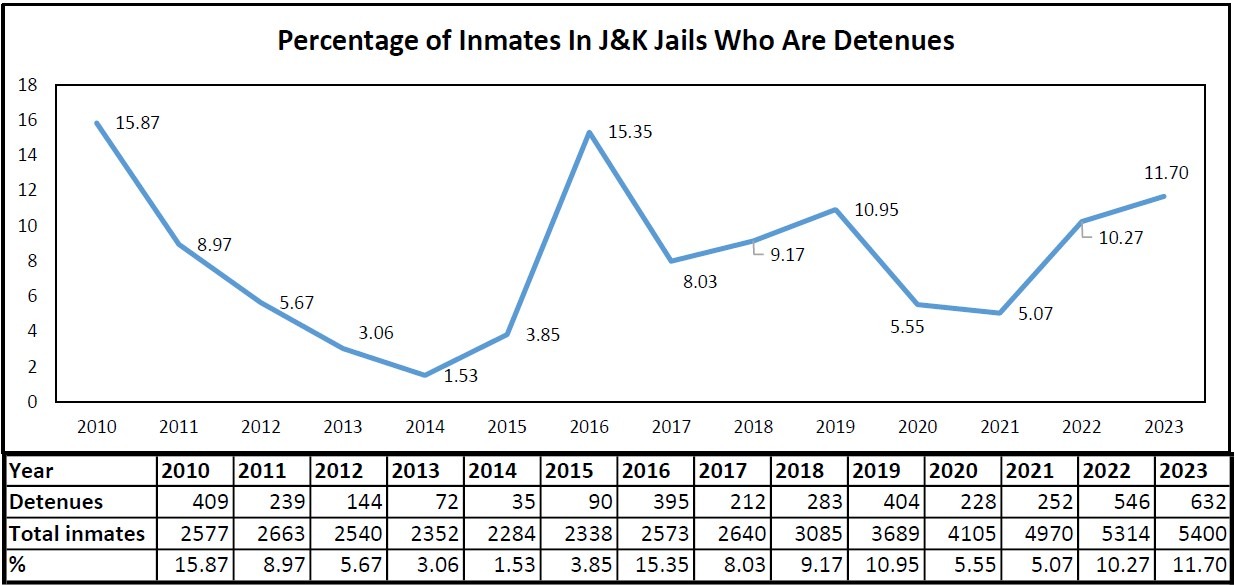

Article 14 analysed National Crime Records Bureau (NCRB) prison data for the number of detenues—defined by the NCRB as “any person detained in prison on the orders of competent authority under the relevant preventive detention law”—and the total number of inmates in jails in J&K at the end of each year since 2010.

The data showed significant spikes in the percent of detenues in certain years: 2010 (15.87%)—a year of unrest in J&K after the killing of three young Kashmiris by security forces in a fake encounter, 2016 (15.35%)—the year of the death of Burhan Wani, a well-known militant leader, and 2019—the year the Modi government revoked J&K’s partial autonomy and converted it into a Union Territory amid widespread unrest, civil liberty crackdowns, and mass detentions.

The last two years for which data are available, 2022 (10.27%) and 2023 (11.70%), show that the use of preventive detention remains high even in the absence of large-scale unrest, and it is increasingly used as a tool of repression and control in the region.

“The high number of PSA detainees, coupled with extremely low conviction rates overall, underscores the capacity of such laws to detain individuals for extended periods without trial, raising serious questions about personal liberty and administrative overreach,” Rehman said.

Chief Minister of J&K, Omar Abdullah, called the PSA a “discredited instrument of repression,” insisting there was no justification to apply it against a legislator.

The Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP), which has 28 of 95 seats in the state legislature, defended the move. A senior party spokesperson argued that the line between representation and provocation had been crossed too many times.

“Development demands cannot come by abusing officers or mobilising people. The government has acted within its mandate,” advocate Sajid Yousuf, of the BJP, told Article 14.

Broader Patterns Of Preventive Detention

Preventive detentions under the PSA are intended to maintain law and order or address security concerns, but have historically been misused to quash dissent against the government and, lately, against journalists (here and here).

However, recently, the law has also been used against individuals raising social and environmental issues, including activist Rehmatullah Paddar from Doda, who protested poor waste management and inadequate public services.

A further five local union leaders and environmental activists had been detained under the PSA in November 2024 after speaking out against hydropower projects in the region.

The J&K High Court has routinely quashed such PSA orders (here, here, and here) with harsh words for the government, citing a lack of substantive reasons and procedural errors in their issuance.

Article 14 previously reported on how Justice Atul Sreedharan quashed four such detention orders (here, here, here and here), where he ruled the prosecution failed to provide sufficient evidence.

Justice Sreedharan was transferred from the High Court of J&K and Ladakh, 26 days before he was set to become the chief justice, to the High Court of Madhya Pradesh in March 2025.

He was then transferred to the Allahabad High Court—where he ranks seventh in seniority, effectively removing him from the High Court collegium and ending his role in judicial appointments—after the Centre requested reconsideration of an earlier proposal recommending his transfer to the Chhattisgarh High Court, where he would have been the second-highest-ranking judge.

From Livestream To Lockup: Dossier And The Arrest

Almost immediately after his heated exchange with the DC, Mehraj Malik went live on Facebook and accused the administration of favouritism and the Doda DC of undermining the people's mandate by failing to consult locals on administrative decisions.

The dossier stated that he “spread false information to more than two lakh followers”.

The dossier accuses Malik of “provoking the public to burn government offices and to act as Lashkars like Burhan Wani”, referring to a militant youth killed in 2016. It also alleges that he encouraged drug use among youth, a behaviour the document interprets as having “every propensity to benefit evil designs of organisations like militant groups and enemy states.”

On the morning of 8 September, Malik was detained at a government guest house, also locally referred to as a dak bungalow, in Doda. According to acquaintances, who spoke to Article 14, Malik stayed overnight there after a day of constituency visits and public meetings.

“Security personnel arrived, restrained him, and escorted him out while bystanders protested," said the eyewitness, who wished to remain anonymous.

Just before his capture, Malik recorded a brief video from inside the bungalow, claiming that officials were preventing him from visiting flood-affected villages.

He was initially lodged in the local police lockup before being formally served with a preventive detention order under the PSA and transferred to Kathua District Jail, nearly 200 kilometres away.

The detention order cited the “gravity of his repeated misconduct, provocative public statements, and mobilisation of villagers” as the grounds for his arrest.

Malik has faced 18 FIRs, the first registered in 2014 under sections 353 (Assault or criminal force to deter public servant from discharge of his duty), 323 (Voluntarily causing hurt) and 504 (Intentional insult with intent to provoke breach of peace) of the now repealed Ranbir Penal Code, 1989, according to the PSA dossier.

Another of the earliest cases, registered at Gandoh police station in 2016, alleged that Malik led a mob that “broke open the office of the Rural Development Department and ransacked it.”

In 2021, he was accused of threatening revenue officials during an anti-encroachment drive, while an FIR registered in 2024 alleged he instigated public unrest during election rallies.

Another FIR, filed this year, accused him of threatening a doctor at the Government Medical College, Doda, on Facebook Live and entering a labour room with cameras.

Other FIRs document protests, alleged intimidation of officials, and disruptions of government programmes, with some officials branding him a “self-styled leader indulging in goondaism.”

Advocate Rehman said, “The language of the dossier makes clear that his political activism, especially where it challenged entrenched administrative or economic interests, is reinterpreted as disorder and violence. Only a few cases are sensible; most of the cases are based on his political activism.”

‘Politically Motivated’

Following Mehraj Malik’s habeas corpus petition, titled Mehraj Din Malik v. Union Territory of Jammu & Kashmir and Others, the court issued notices to the principal secretary, home department; district magistrate, Doda; senior superintendent of police, Doda; and the superintendent of the District Jail, Kathua.

The respondents were directed to submit their replies by 6 November 2025.

The petition begins with a sharp assertion that Malik’s detention is “illegal, arbitrary and politically motivated,” and violates his fundamental rights under Articles 19(1)(a) and 21 of the Constitution.

It seeks the quashing of the detention order and demands compensation of Rs 50,000,000 for what it called “the unconstitutional curtailment of liberty”.

Malik’s counsel argued that the PSA, “a law meant to safeguard public order”, had been turned into a weapon “to silence a democratically elected legislator who was vocal on issues of corruption, employment and governance.”

The petition described Malik as an outspoken public representative who “raised issues of common people fearlessly in the Assembly and on social media,” often drawing criticism from the local administration and political opponents.

The plea pointed to “serious procedural lapses” in the detention process, claiming that Malik was never given the grounds for detention or the documents relied upon by the authorities.

Article 14 has previously reported on at least two cases (here and here) where the courts quashed PSA detention orders for procedural lapses.

The petition further alleged that the initial police dossier was “suppressed” and replaced with a re-submitted version dated 7 September 2025, prepared after what it calls “politically motivated” daily diary reports (DDRs).

According to the petition, the detention is based on 18 FIRs and 16 DDRs, most of which are linked to minor political protests or administrative confrontations.

“Fourteen of these cases are pending before the courts, three have been withdrawn or compounded, and one remains under investigation. None of these, even remotely, threaten public order,” the petition reads. It calls the invocation of the PSA in such a situation “an abuse of process and a mockery of constitutional guarantees.”

It also accused the DC of Doda, S. Harjinder Singh, of “personal animosity” and of acting as “judge in his own cause”.

Citing Supreme Court and High Court rulings, the petition argued that preventive detention cannot replace criminal proceedings when a person is already facing trial, adding, “No material on record suggests any imminent threat to public order or security.”

Beyond the legal grounds, Malik’s counsel said the detention has “orphaned an entire constituency politically” while the Chenab Valley struggles with floods and damaged infrastructure.

The petition further accused the administration of trying to malign Malik by “circulating doctored videos portraying him as having made inflammatory statements,” a move it said “further compounds the injustice of his detention.”

Calling for judicial intervention, the petition urged “the restoration of the rule of law”, insisting that “personal liberty, the most cherished fundamental right, cannot be curtailed on whim or administrative prejudice.”

Advocate Mujeeb u Rehman said the petition had “struck a chord well beyond the courtroom” and that the case was “about how security laws continue to collide with democratic freedoms in Jammu and Kashmir.”

The next hearing for the case is scheduled for 7 November.

Public Response And Protests

The news of Mehraj Malik’s detention sent ripples through his native village of Tandla, 70 kilometres east of Doda town. Villagers, whether working in the fields or resting at home, converged at the village chowk as whispers of the arrest quickly escalated into huge protests.

“It was about a larger question his arrest posed. If an elected lawmaker could be jailed, what security does the ordinary citizen have against the machinery of power?” said I*, a protestor, who wished to remain unnamed.

Others carried placards demanding justice and the protection of democratic representation, while discussions on social media amplified the protests, drawing attention from across the region.

Authorities responded swiftly to the demonstrations.

The DC of Doda invoked Section 163 of the Bharatiya Nyaya Sanhita, which gives the administration “power to issue an order in urgent cases of nuisance or apprehended danger”, to prohibit public movement without prior permission, limit gatherings and curb free movement in the district.

Mobile internet and broadband services were also suspended, disrupting communication and access to information.

Mehraj Malik’s father, Shams u Din Malik, described his son as a committed advocate for marginalized communities. “Mehraj cannot tolerate injustice against the poor,” he said. “He raises his voice for the oppressed, yet he is punished instead of being heard.”

*Name changed on request

(Irshad Hussain is an independent journalist based in Kashmir who reports on political, environmental and human rights issues, while Qazi Shibli is the editor of The Kashmiriyat and reports on politics, human rights, environment and social justice issues.)

Get exclusive access to new databases, expert analyses, weekly newsletters, book excerpts and new ideas on democracy, law and society in India. Subscribe to Article 14.