Palamu & Lohardaga (Jharkhand): During an unusually cold week in January 2024, Dhanpatiya Devi’s family of five ate a wild-growing tuber twice a day, every day.

“There was nothing else but gethi,” she said of the dark and hairy potato-like root vegetable that Adivasi communities dig out from the ground in the remote forests of India's poorest state.

“It had been nearly four months since we received rations,” said Dhanpatiya Devi, a frail woman in her late forties.

The gethi offers a starch that is difficult to render edible. Dhanpatiya Devi and others of the Parhaiya indigenous tribe she belongs to—one of 75 ‘particularly vulnerable tribal groups’ or PVTGs by official nomenclature—said the peeled and boiled gethi is left overnight in a straw basket lined with paddy husk, positioned in a shallow riverbank for its bitterness to leach out with the flowing water.

It is then sliced thin and consumed with a sprinkling of salt. Dhanpatiya Devi was incredulous as she handed one sample over.

“You won’t like it,” she said.

Dhanpatiya Devi lives in Surungahi, a small hamlet adjoining Nawadih village in the Ramgarh block of north-western Jharkhand’s drought-hit Palamu district.

From September 2023 through January 2024, none of the residents of Surungahi received their monthly quota of subsidised food grains guaranteed by the National Food Security Act (NFSA), 2013.

When rice was distributed in February 2024, there was no mention of the preceding four months’ quota of rations, said Dhanpatiya Devi.

Across a handful of villages in the Palamu and Lohardaga districts of Jharkhand, the state with the second highest number of multidimensionally poor Indians according to the NITI Aayog’s 2023 report, residents said they experienced months-long periods of being turned away at fair price shops; and many were unable to access any free or subsidised foodgrain for an entire quarter even though the NFSA made food and nutrition a right that poor Indians can demand.

At the end of 2023, the government of India said it would extend its free foodgrain programme for five years, benefiting 813.5 million people or two thirds of all Indians, at a cost of Rs 11.8 trillion (over $141 billion).

The food security law is central to poverty alleviation measures in Jharkhand.

If it were a country, this state with a 26.2% population of indigenous people would have a per capita gross domestic product equivalent to Cameroon, the Central African nation that has faced recent political instability and terrorism. Nearly 35% of the rural population of the state is multi-dimensionally poor, and 40% of the total population faces deprivation in nutrition, 69% in cooking fuel and 43% in sanitation facilities.

Yet, the crucial safety net of the world’s largest food support programme has been saddled in Jharkhand by exclusions (see here and here), unexplained disruptions in supply, deletions (see here, here) and delays (here). Experienced along with the current drought in Jharkhand and the consequent migration for livelihoods, the inability to access rights conferred by the NFSA makes food insecurity a recurring problem for some of India’s most marginalised people.

In Surungahi, Gauri Devi said she spent most of the money her husband deposited into their bank account, which she withdrew at the nearby common services centre, on food and essentials. Her husband is one of 20-odd men from the hamlet picked up by a bichholiya (labour contractor) for a months-long stint at a construction site near Hyderabad, Telangana, nearly 1,300 km away.

“He went away when the drought began,” Gauri Devi said, “to earn something so the kids have everything they need.” Surungahi’s residents were all in agreement that the first casualty of the missing or irregular food aid was higher education for their children. “Because he’s working in Hyderabad, we at least have enough to eat, but nothing more,” according to Gauri Devi.

Notebooks As Ration Cards Record No Exclusions

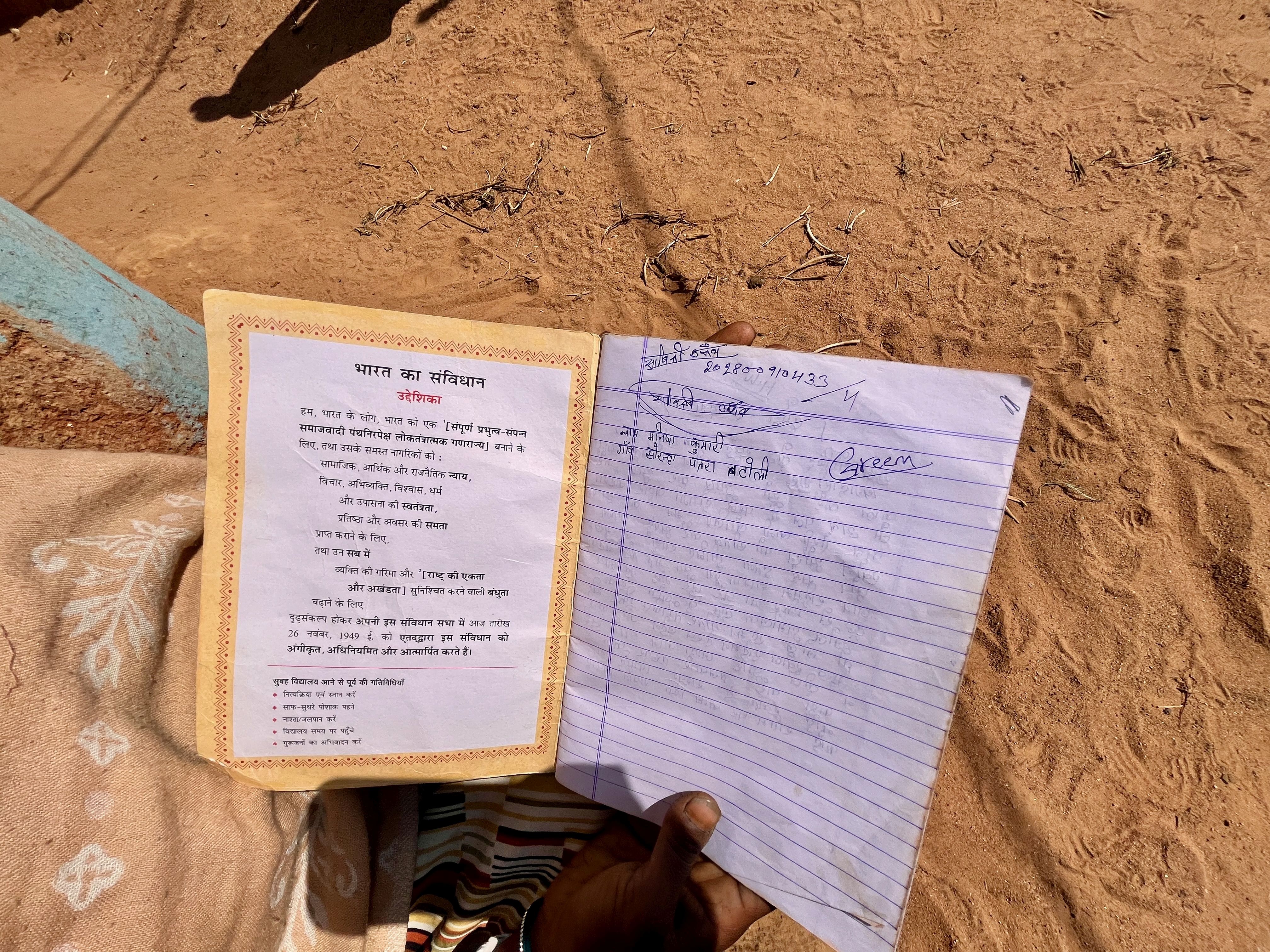

In Bhandra block of Jharkhand’s Lohardaga district, 60 km west of state capital Ranchi, most residents of Bhaunro Patra Toli, a hamlet inhabited mainly by families belonging to the Oraon tribe, invested Rs 10-Rs 20 each in long notebooks that they began to use as their ration cards once the state-issued booklets ran out of space to note grain disbursals made to them through the public distribution system (PDS).

Unintelligible rows of numbers, dates and other scrawlings by dealers or assistants fill the pages of these ‘ration cards’. The books do not bear even an official rubber stamp.

“The dealer asked me to pay money for a fresh card,” said Dayamani Oraon, whose household income is limited to the Rs 1,000 pension received in her disabled husband’s bank account, and anything the 30-something mother of four is able to earn as day wages.

She did not know which months’ rations she received and which were skipped, but said she thought foodgrain was unavailable for a couple of months.

Some residents said officials at the block level claimed the printed ration cards no longer held much value as the PDS now has digitised records of every beneficiary.

“But how will we know if we got everything due to us?” asked Dayamani Oraon.

Shaniaro Oraon, an activist in Lohardaga who also belongs to Bhaunro Patra Toli, said that in the absence of a clear and official record, it was difficult to verify if villagers had availed their quota of food grains. The fair price shop was 3 km away, a distance most women covered on foot, sometimes returning without the monthly rations.

To protect individual entitlements and establish a unique record of eligible card-holders, the government of India has mandated seeding of Aadhaar cards with ration cards.

“Sometimes the computer does not recognise the fingerprint, so a day is lost,” Shaniaro Oraon said. On some other occasions the beneficiaries are turned away because there was no grain stock.

Over time, this meant that card-holders, in a district where 56% of the population comprises tribals, had no simple way to cross-verify what entitlements were pending, or if there had been a fake transaction recorded in their names. The notebooks are used across several parts of Jharkhand, in Lohardaga, Palamu and Gumla districts.

Those using notebooks as ration cards as well as others said it was routine for some family members to be excluded. The NFSA assures 35 kg of food grains per household for Antyodaya Anna Yojana (AAY) card-holders, identified as the poorest beneficiaries, and 5 kg per person for priority household (PHH) beneficiaries.

Three of Dayamani Oraon’s children, aged 8, 9 and 11 years, are not listed in her ration card despite her having given applications twice to the marketing officer, a block-level government employee overseeing the functioning PDS.

Half a dozen other women in Bhaunro Patra Toli immediately said they faced the same challenge. Maharangia Oraon, 26, said her name was added after she paid “cheh sau paise” for a new, printed ration card with her included as a beneficiary. She meant Rs 600.

Maino Oraon, 40, found out a couple of years ago that her family was registered as a beneficiary in Lalpur village of Gadarpur panchayat, 5 km east from Bhaunro Patra Toli in the same block. Only her name and one son’s name were included as beneficiaries, leaving out her husband, a daughter and a second son.

Shanti Oraon, whose husband is away working as a cleaner at a hospital somewhere in Kerala, about 2,500 km away, said her son’s name was not included in their card despite multiple attempts. The beneficiary names were jumbled up too—her father-in-law Birsa was listed as 19 years old, mother-in-law Etwarya as 17 years, while her son Prakash’s name was left out.

Listed as the card-holder is Akash, her elder son, shown as 73 years old. Under the NFSA, the eldest woman of the household aged 18 years or more is normally designated as the head of the household for the purpose of issuing a ration card.

Bahumani Oraon, another resident, said he received rations for his wife, two sons and a grandchild, but not for his daughter-in-law and her younger child.

Women Face Additional Exclusions

About 10 km away, in Dhanamunji village located up a bone-dry hillock, Rukmini Kumari has not been a beneficiary of the NFSA since getting married in 2019. Her husband, who died in a road accident in March 2023, was himself not a beneficiary, having had an old Bihar ration card before the state of Jharkhand was formed.

Belonging to the Lohra indigenous tribe, the couple applied for a new ration card online during the Covid-19 pandemic, not very hopeful, and also submitted their documents twice with the marketing officer at the block office.

“Tangra dekh ke baithi ho,” her mother-in-law rebukes her, Rukmini Kumari told Article 14 one February afternoon when she was alone in their mud home with a low tiled roof. Translated literally as sitting around gazing at her legs, the comments were a daily berating of the young widow with two little daughters to care for, thus unable to work as a labourer.

Her husband owned a small plot of land, about half an acre, which they last tilled two cropping seasons before he died. With the rains playing truant in Lohardaga over two consecutive drought years, the land has remained fallow. “There is neither water nor money for seeds,” Rukmini Kumari said.

Food grains through the NFSA would be a lifeline for the single mother, said Shaniaro Oraon, adding that Rukmini Kumari has also been unable to obtain pension under a pan-India scheme for social security for widows; while an application for a house under the showcase public housing programme Pradhan Mantri Awas Yojana has also not met a favourable response. The PMAY’s ‘housing-for-all’ goal was to be met by 2024.

Rukmini Kumari lives on whatever groceries her mother, who lives about 35 km away, can spare. Her daughters, Manisha, almost 4 years old, and an unnamed one-year-old, also get a daily hot meal at the anganwadi centre, a key supplementary nutrition scheme for children under the Integrated Child Development Services (ICDS) scheme.

The hot meal is mandated by schedule II of the NFSA, specifying a daily intake of 500 calories and 12 grams of protein for primary school children, or take-home rations of a commensurate quantity.

Still five months short of her fourth birthday, Manisha Kumari walked everyday to the anganwadi centre with the other children of Dhanamunji, ate her meal and brought back some in a little round steel box for her baby sister. The cold dal-chawal-sabzi was the infant’s most nutritious daily meal, the tired mother conceded.

Women finding themselves removed from the ambit of the NFSA upon marrying and relocating to the marital home was a common tale.

In Bhaunro Patra Toli, Yashoda Oraon was never added to her husband’s ration card though her name was cancelled from her maternal home’s ration card four years ago when she got married. Her husband is 200 km away, working at a brick kiln in Gaya, in southern Bihar. His wages are Rs 150 for every 1,000 bricks made—Rs 2,700 to Rs 3,000 a week if he is able to make up to 20,000 bricks over seven days.

At a little over Rs 400 ($ 4.80) a day, it is better than day wages closer to home, but entails gruelling labour for 12-15 hours a day. “I went to the brick kiln last year,” said Yashoda Oraon, in her early twenties, “but those earnings are lost to doctors and medicines.” She was sickly from the back-breaking work at the brick kiln, she said.

During the months that her husband is away, she earned Rs 100 a day as a farm labourer, but only when work was available. Apart from that spare cash, she depended entirely on her husband’s quota of PDS food grains for nutrition.

Silent Cards And Green Cards

Allocation and distribution reports show 90% and above disbursals through the year, across districts and most blocks, even though activists and residents said thousands of beneficiaries had not received a regular monthly supply of food grains in August-December 2023.

However, official data also showed that as of September 2023, seven lakh ration cards in Jharkhand had not lifted rations for three months, and were termed ‘silent’ ration cards. Over 18,000 of these were AAY cards—inexplicably, thousands of the poorest were not collecting free or subsidised food grains.

Not only did Jharkhand account for over 45% of the nationwide total of 16 lakh silent ration cards, but the state also recorded over 10% of its 6 million ration cards as ‘silent’. Activists said it was unclear if those turned away from fair price stores during this period may have also been called silent ration card holders, their cards at risk of suspension or deletion.

The state government of Jharkhand, in November 2020, announced that those not covered by the central NFSA scheme would be given subsidised food grains under a state government scheme. These would be the ‘green card’ holders of Jharkhand.

Families living below the poverty line in the state and not already covered by the NFSA were to be given a green ration card by the state government and be entitled to 5 kg of grains per person at the rate of Re 1 per kilo. Poor families excluded from the NFSA beneficiary list—researchers and activists have said about 100 million poor Indians may be excluded from rations on account of old data derived from the 2011 Census of India—would thus be granted food security through the Jharkhand State Food Security Scheme.

In Bhaunro Patra Toli, many families’ notebook-ration cards had a note on the cover or first page, saying “green card”, indicating they were not covered by the NFSA and had not received state-subsidised food grains until November 2020.

James Herenj, an activist for the right to food and the right to work who has been working among Palamu’s communities for over two decades, said the state government’s move to offer a state scheme for those excluded by the NFSA was laudable, but with the union government holding that the poorest were already covered as per norms, all applications for new ration cards in Jharkhand were now being considered only under the green card scheme.

“This is in violation of the Supreme Court order in the PUCL case, to give all families of primitive tribes Antyodaya Anna Yojana cards,” Herenj said.

He was referring to People’s Union For Civil Liberties Vs Union Of India, filed in 2001, a landmark case in the right to food struggle by civil society organisations.

The AAY cards provide 35 kg of food grains per family, the highest allocation among all categories under the NFSA, but for the desperately poor with large families and little to no income from farms or wage labour, even this quota proves insufficient.

Moti Korwa, a labourer who has seven daughters, returned to Surangahi in January after several months of construction labour in Hyderabad at Rs 350/Rs 400 per day. “PVTG couples are discouraged from getting the operation,” he said, referring apparently to the tubal ligation procedure, a sterilisation surgery for women. (Various sterilisation procedures are denied to PVTGs in some states, ostensibly to protect them, though other birth control measures continue to be available.)

Moti Korwa’s wife said she cooks nearly 2 kg of rice per meal. “So you can imagine the struggle upon not receiving the ration for months.”

Climate Crisis Heightens Food Insecurity

In Sarahua village of Palamu’s Ramgarh block, Sohadra Devi dragged out a sack of aitheni, a wild-growing spiral-shaped vegetable about the size of a child’s finger and as hard as leather. Over weeks of foraging in the winter, she filled a sackful of the forest produce that local Korwa and Parhaiya tribes, both PVTGs, consume particularly in times of distress.

Agricultural practice being poorly developed in and around villages such as Sarahua, the mostly small-holder villagers continue to also use traditional hunting-gathering skills. Paramsiska Kuwar (a title taken on by widows) displayed her stock of chakwod, a twig-like plant that locals thresh lightly for it to open up, revealing hard little bean-shaped peas inside that are boiled and consumed.

Growing wild on their sparse rain-fed farms, alongside small patches of mustard and wheat and green peas, is bathua, a kind of spinach called chenopodium or goosefoot in English and parippukeerai in Tamil.

The Parhaiya and Korwa women hold in their kitchen practices a deep knowledge of what can be foraged and when—the Betla national park and the Daltonganj forest are barely 20 km-40 km from Ramgarh, and on the fringes of these forests was dense wild growth that was once a rich food source.

“We always find gethi or aitheni or chakwod,” said Paramsiska Kuwar, “but not as easily as we once used to.”

Sarahua’s residents said their families were growing even as the surrounding forests were assailed by forest fires, deforestation for infrastructure projects, illegal tree-felling, etc.

There were no young men in Sarahua on a Monday in February, most of them away at brick kilns and labour construction sites in Uttar Pradesh, Bihar, Telangana and Kerala.

Several of the key observed impacts of climate change, as identified by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change’s (IPCC) sixth assessment report directly impact food security for vulnerable populations, and many of these are now visible in Jharkhand’s second consecutive year of drought. These include slowing growth of agricultural productivity, negatively impacted crop yields, with negative consequences for food security and livelihoods, and particularly so for vulnerable groups such as women, children, low-income households, indigenous/ minority groups and small-scale producers.

The IPCC report said these vulnerable populations were at higher risk of malnutrition, livelihood loss, rising costs and competition for resources.

Herenj, the Palamu-based activist, said he led a team to villages including Sarahua around 10 December 2023. “Our assessment was that the 1,600 families who were PDS card-holders in Ramgarh block were all badly affected by delays and non-disbursal of rations,” Herenj told Article 14.

At the time, some had not received rations for up to four months. Some families later received two months’ rations together.

Herenj, who is the state convenor of civil society group Jharkhand NREGA Watch, said poor families were unable to depend on the Mahatma Gandhi National Rural Employment Guarantee Act (MGNREGA), 2005 that promises 100 days’ wages every year because long delays in payments and other problems had turned people away from the jobs guarantee programme. “The months-long delays in payments force people to lose interest in NREGA,” he said, “and we fear that this will become a stamp of approval for the government to simply close the programme altogether.”

Suhagi Kuwar, in her fifties, said during the four-month gap in receiving rations towards the end of 2023, the women asked one another for small quantities of rice or millets, and a few took cash loans from a local bania (trader). “The problem with taking a loan is that it has to be repaid,” she rued, “and there is rarely a new source of income to repay a loan with.”

The women said they heard that in a nearby village, a grocery store owner or PDS dealer collected residents’ ration cards, advanced them some quantity of food grains, and then kept the card-holders’ entire quota when disbursal finally resumed in January and February 2024.

In the last four to five months of 2023, reports emerged of ration supplies being affected in large parts of the state, including of a reduction in allocations from the centre (see here, here), and of irregularities in the mechanism to track distribution (see here). Dealers in one district reportedly told beneficiaries their quotas were curbed to recover the government of India’s expenditure on Chandrayaan, the mission to the moon.

Lower Farm Incomes, More Out-Migration

Exacerbating the food insecurity were the low incomes in recent years from the sale of traditionally grown agricultural produce.

In 2023, Angani Oraon of Bhaunro Patra Toli harvested 40 sacks of potatoes from her small land holding. A sack of potatoes averages 35 kg to 40 kg of potatoes, taking her total harvest to nearly 1.5 tonnes.

“I didn’t find a buyer even when I dropped the price to Rs 3 a kg,” she said. She brought her produce home and began to give away potatoes to anybody willing to have them, also cooking the starchy vegetable everyday at home. The remainder she left to rot.

Transporting the potatoes from her village to the nearest market cost her Rs 15 per sack, or Rs 600 in all. Like many others in the village, she had rented a tractor to prepare the soil for sowing, a two-hour job at Rs 1,200 an hour, and later Rs 200 a day for a couple of locals who worked on the harvest.

Based on that calculation, the Rs 4,500 that Angani Oraon wanted at the bare minimum for her season’s harvest barely crossed the breakeven point, but the cash would have been useful, she reasoned.

Everybody in the village produced some potatoes, and they all met with the same fate. Yashoda Oraon said the family treated their 15 sacks of potatoes as a food staple for the year. To avoid the transport costs, Jatri Oraon left most of her potatoes unharvested.

Most households in the hamlet sent menfolk away to work in the cities. Some went for a few weeks or months to Ranchi, others went as far as Kerala for six to 10 months at a time.

In Bhaunro Patra Toli, Dhanamunji, Sarahua, Surangahi and Nawadih, as in dozens of villages in Lohardaga, Latehar and Palamu districts, there are almost no men belonging to the working age still at home.

Sarahua resident Balmukund Korwa, in his sixties, said the big draw of the brick kilns was the advance payment from labour contractors, sums ranging from Rs 30,000 to Rs 75,000.

Two of his three sons, in their twenties, were in Bihar, at a brick kiln. “There’s no other way to get a lump-sum,” Balmukund Korwa said. Lump-sums are critical to farming season investments, home repairs, weddings, higher education and medical emergencies.

Left behind for many months at a stretch, the women, most with lower average levels of literacy, fell prey to frauds and rackets related to the all-important monthly ration.

Suhagi Kuwar paid Rs 350 to a local middleman a few days earlier, for a printed ration card that is normally provided at no cost. She saw it as an investment towards ensuring an interrupted monthly supply of her entitlements.

“Nothing is free,” she said, “so I gave whatever I had saved to get my rations.”

(Kavitha Iyer is a senior editor with Article 14 and the author of ‘Landscapes of Loss’, a book on India’s farm crisis.)

Get exclusive access to new databases, expert analyses, weekly newsletters, book excerpts and new ideas on democracy, law and society in India. Subscribe to Article 14.