Updated: May 6, 2020

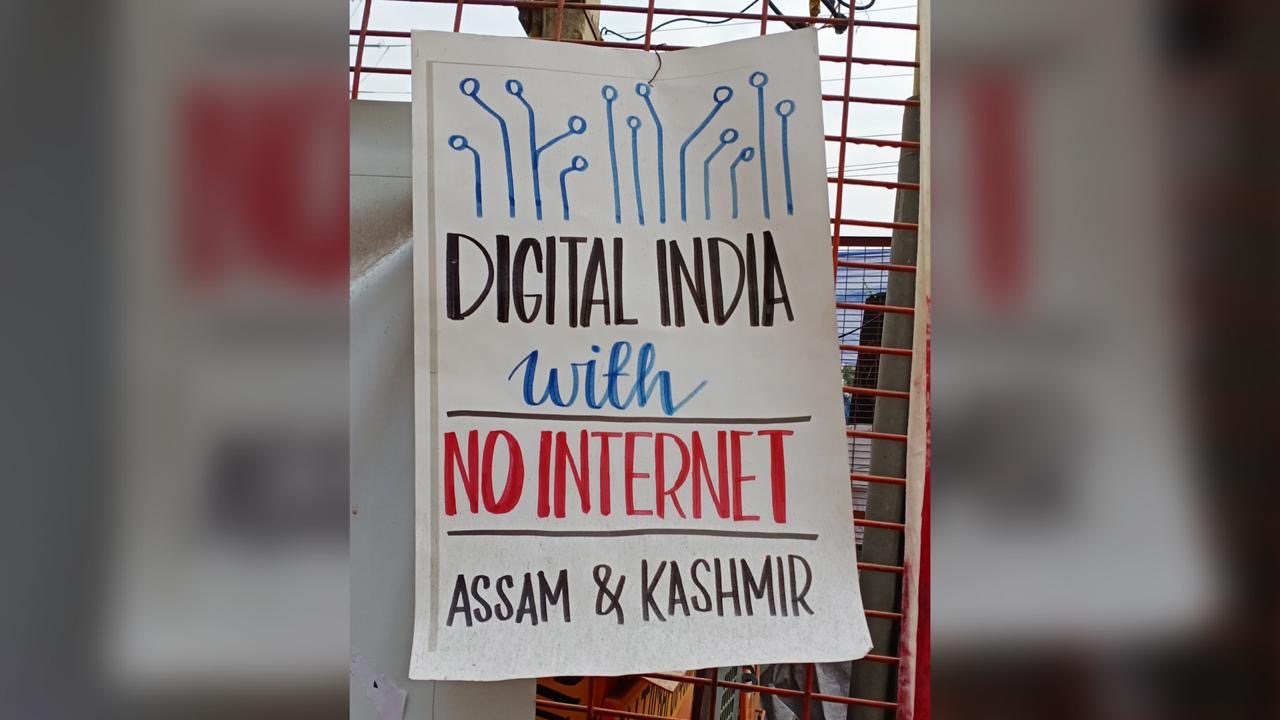

New Delhi: Despite the Supreme Court and the Kerala High Court constitutionally protecting the “access to Internet” and granting it a “fundamental” status respectively, the Indian government has now argued it is not, citing a Pakistani-fuelled insurgency, to curtail bandwidth to second-generation wireless, or 2G, which it contends is enough for "normal life” in Jammu and Kashmir (J&K).

Both arguments do not appear to be backed by fact:

Over the decade to 2018, as the number of wireless telecom subscribers grew 524%, terrorism-related violence dropped 1%, according to South Asia Terrorism Portal data; deaths in such violence fell 23% over the same period according to the government’s own data.

Slow Internet has indeed crippled “normal life”, speeding the spread of the Coronavirus, preventing work-from-home options that the government recommends, shutting local tech companies or forcing them to relocate, and as a petition in the Supreme Court details, preventing virtual classes, telemedicine and court proceedings via teleconference, as is now the norm in locked-down India.

“Since 1990, 41,866 persons have lost their lives in 71,038 incidents throughout the erstwhile State of J&K. This includes 14,038 civilians, 5,292 personnel of security forces and 22,536 terrorists,” the government said in the Supreme Court on 26 May 2020, in response to 31 March petition filed by an advocacy, Foundation for Media Professionals (FMP), which asked that the ban on 4G mobile services be rescinded.

“Modern terrorism relies heavily on the internet,” said the government affidavit, arguing that terrorist activity on the Internet is not easily traceable and “provides an easy inroad to ‘young impressionable minds’.

The Centre on 4 May 2020 argued that the pandemic has had “absolutely no impact” on “chronic anti-national activities from across the border”. Instead, there has been a “surge” in terrorist incidents post pandemic, the government said, referring to firefights in Kupwara on 5 April 2020 and in Handwara on 3 May 2020, which resulted in the death of 10 soldiers and police officers.

Between 2008 (when 3G was first introduced) and 2018, there was an inverse correlation between the number of mobile users and violence in the valley. As per a 2019 Department of Telecom report, the number of wireless telecom subscribers in J&K increased from 2.20 million in 2008 to 13.72 million in 2018, up 524% over the decade.

Over the same period, terrorism-related violent incidents dropped from 602 in 2008 to 598 in 2018, according to SATP and “Fatalities in Terrorist Violence” decreased 23% In Kashmir, from 505 in 2008 to 387 in 2018, according to Ministry of Home Affairs data.

“After a near-continuous decline in terrorism-linked fatalities after the peak of 2001, fatalities had bottomed out in 2012 at 121 (the government says 99),” said SATP’s 2020 assessment report of terrorism in the Valley.

The data undermine the Centre’s argument in the Supreme Court that the Kashmir insurgency is the reason for slow-speed internet.

Court Hearings Plagued By Glitches

In a virtual hearing, meaning over videoconference, plagued, ironically, by poor and dropped connections on 4 May 2020, senior advocate Huzefa Ahmadi, who represented the FMP, argued that restrictions on high-speed internet, especially during a pandemic, violated fundamental rights. “Let them open internet speeds for a week, and see if there is any nexus with terrorism,” said Ahmadi. “They can consider week by week.”

He pointed out that both the terror-related incidents the Centre referred to took place when restrictions on high-speed internet were in place.

The Internet was frequently snapped in J&K before the 5 August 2020 abrogation of a special constitutional provision, Section 370, but after it stayed off for 212 days after that, before being restored on 4 March 2020. After the Coronavirus pandemic broke, the internet was slowed to 2G speeds on 26 March 2020 “to maintain public order”; this high-speed ban, which was supposed to remain in effect till 3 April 2020, has been extended thrice, with the latest extension till 11 May 2020.

The Centre on 26 April 2020 argued that slow bandwidth is “reasonable” and “least restrictive”, given Pakistan’s encouragement of terrorism. “The world is fighting a war against an unprecedented pandemic”, said the government petition, but “unfortunately” J&K is fighting the Covid-19 pandemic and terrorism, which “is being aided, abetted and encouraged from across the border”.

In 2016, the United Nations Human Rights Council held that access to the Internet is a fundamental right. Three years later on 19 September 2019, the Kerala High Court echoed this sentiment when a student in Kozhikode, Kerala, challenged a mobile-phone ban between 6 pm and 10 pm in a girls' hostel.

Four months later, on 10 January 2020, the Supreme Court constitutionally protected the right to access the Internet. The right to “freedom of speech and expression under Article 19(1)(a), and the right to carry on any trade or business under 19(1)(g), using the medium of internet is constitutionally protected,” it had said.

Free speech and express has been under stress in J&K for years, and the right to business via the Internet is clearly being crippled by slow Internet. The FMP petition records how doctors, teachers, students, journalists and lawyers struggle with slow Internet. An examination of three key areas, telemedicine, education and the judiciary, reveals how.

Telemedicine

When doctors and patients cannot meet face to face, the Internet is an indispensable tool, said Riyaz Daga, PhD, spokesperson for the Doctors Association Kashmir (DAK). “You cannot diagnose a patient on the phone,” said Daga speaking to Article14. “If we had 4G we could video call.” Complicated surgeries that require consultations are “out of the question”, he said.

“I wish I had 4G, it took me whole night downloading a paper so that I could prepare for an upcoming ER duty. An internet connection, especially in a pandemic, is like an eye to the emergency physician. Kindly don’t blind us in that eye,” Khawar Achakzai, a doctor at Srinagar’s Government Medical College tweeted.

The government told the Supreme Court that “health related and other important information about Covid-19, including documents and advisories issued by the government on its websites, are being accessed by over 100,000 professionals in various health facilities in J&K through fixed line high-speed internet”. That does not help doctors who use mobile phones, as the majority do.

“Various Government websites like website (sic) of WHO, Ministry of Health and Family Welfare, etc. associated with timely information flow in the form of awareness/advisories/orders can also be easily accessed at Low Speed internet,” the government said.

Doctors disagree.

Education

It takes Dheeba Nazir, who teaches Kashmiri to class 7 students, three hours to upload study material for the day, a video less than six-minutes long.

“Network connectivity is anyway low, so I started the upload at 7:25am and after several tries, finally managed to send the video at 10:29am,” she said, adding that she was unsure if her students could download the video.

"The Centre submits that one hour of classes via television is being given. How can we complete the full syllabus with one hour classes per day?” lawyer Salman Khurshid told the Supreme Court on 4 May 2020. “Classes need to be interactive which is only possible through videoconference. Issue is not if it's possible to download via 2G but of the time it takes to download.”

“Education in the valley was interrupted in post-August 2019 when schools were shut down in the aftermath of the revocation of J&K’s special status,” argued Nazir. “This year, the coronavirus has wreaked havoc. A child has thus missed out on two years’ worth of education.”

An association of private schools in Kashmir has also filed a plea urging the government to restore 4G internet.

The Centre argued that a “majority of students of class 1st to 12th are studying in 24,018 government schools as compared to 5,690 private schools”. Since a “majority of government school students do not have mobile/smart phones or computers to access the internet”, the Ministry of Human Resource Development “has initiated some technology-based initiatives for e-learning and further proposal is being shared with it for delivering lessons on 16 DD Channels at national level.”

The government claimed e-learning apps were “easily downloadable and the video lectures can be browsed without any issue over 2G internet”.

Judiciary

Since the end of March 2020, the Jammu and Kashmir High Court has heard only urgent matters through videoconferencing, but the slow Internet cripples that process.

Advocate Salih Pirzada, who filed a plea on behalf of Azra Ismail, a Srinagar based advocate, seeking a comprehensive policy to prevent and control the coronavirus, said it was ironic that he has missed “a number of hearings” because he cannot connect to the app that links to judicial videoconferences.

“Filing a petition is not an issue, since we have to email our pleas,” said Pirzada. “The problem starts once we start arguing matters. The app used for videoconferencing is supported by 4G internet only.”

“The Vidyo App used for the virtual hearings required a certain bandwidth which cannot be supported by the broadband internet here. “Non-availability and restrictive internet is hampering access to justice,” said Pirzada..

The Centre has rejected these arguments, saying it can provide “designated” computers that lawyers can use, if they do not have computers linked to the Internet.

India's Frequent Internet Lockdowns

There were 385 internet shutdowns in Jammu and Kashmir between January 2012 and 15 March 2020, of which 237 were preventive “in anticipation of law and order situation”, according to internetshutdowns.in; 148 shutdowns were reactive, “imposed in order to contain on-going law and order breakdowns”.

India had the “highest number of internet shutdowns”, 54 in 2016 and 2017, according to data from Access Now, an advocacy for digital rights.

“Disrupting internet access during this critical period will prevent people from accessing timely information about the COVID-19 virus, thereby aiding its spread and gambling with people’s lives,” Felicia Anthonio, Access Now’s Campaigner, #KeepItOn Lead said in a 24 April 2020 statement.

Avinash Kumar, Executive Director of Amnesty International India, an advocacy, said a “public health emergency is not an opportunity to bypass accountability.”

“The people of Jammu & Kashmir are entitled to live with dignity and be informed of the threats that COVID-19 pose to their health,” said Kumar in a 19 March 2020 statement. “Measures must be taken to protect people’s human rights in the region of Jammu and Kashmir and not further weaken them.”

(Ritika Jain is a Delhi-based freelance journalist)