New Delhi, Cambridge (UK) and Hyderabad: On 27 February, 2024, a union government committee approved the clearing of over 450 hectares of lush forests—prime habitat for elephants, sloth bears, leopards, hyenas and other threatened wildlife species—in the hills of Jeypore and Malkangiri in southern Odisha for a new railway line.

The cutting of these forests was cleared by a regional empowered committee (REC) of the ministry of environment forest and climate change (MoEFCC), one of 10 set up under the Forest Conservation Amendment Act (FCAA), 2023 to vet proposals submitted by states for “forest diversion”—the official term for cutting forests and replacing them with roads, dams, power plants, mines and other infrastructure.

The loss of such wildlife and its ancient habitat was compounded by a new fiddle with the law, which requires “compensatory afforestation”, itself a much-criticised concept (here, here and here) that requires any forests cleared to be replaced with the equivalent area of man-made forests.

The land for the compensatory afforestation for the Odisha rail line will be 100 hectares of what is called “proposed reserved forest”, already a forest owned by the state government but which is not notified, meaning it is not officially under the purview of the Indian Forest Act, 1927, or equivalent state laws.

So, saplings will be planted on land that is already forest—by the state forest department, which is paid by the company or agency to whom forests are handed over—to compensate for the forests lost to the railways.

The ‘afforested’ land—often a different biome, such as grassland, mountain deserts or scrub forest—remains with the forest department, but does not mitigate the loss of forests they replace, likely causing more harm by irrevocably altering the ecology, damaging resident wildlife and impinging on the rights of local people who depend on these forests.

The other compensatory component of the Odisha rail line is that the railways will pay for the afforestation of 816 acres of degraded forests in an area called the Malkangiri forest division. This is contrary to compensatory-afforestation principles, since the railways will not provide non-forest land to replace the forests being cut for the railway line.

The Odisha rail line was one of 56 such “forest diversions” approved by the MoEFCC and its regional offices in seven months after 19 February 2024. This means more than 1,300 hectares of forest will be cut for mines, dams, highways, steel and power plants and more.

The forest cleared for dams, roads, railway lines and more continue to remain as ‘forests’ on record, inflating India’s official forest area. The area afforested is also—falsely—counted as an increase in forest while it is already accounted for as government forests.

Such clearing of forests by abandoning legal checks and balances is likely to further endanger wildlife, destabilise ecosystems, jeopardise the livelihoods of forest-dependent communities and India’s ecological security.

Defying The Law

Most of these diversions contravene a basic compensatory-afforestation tenet of the environment ministry: providing “non-forest land for (loss of forest) land,” and defy three Supreme Court orders, including the latest 19 February 2024 interim order in a case that challenged the constitutionality of the FCAA.

The FCAA was criticised for nullifying the Supreme Court’s 1996 Godavarman judgement by restricting the definition of forests to only include notified and recorded forests. This would strip vast swathes of forests—guesstimated at 27%—of legal safeguards, including clearing them for development.

Forests cover no more than 21% of India’s land—of which only 12-13% are dense forests—against a national target of 33.3% in the plains and 66.6% in the hills. Under the current mechanism set by the FCAA 2023, it cannot hope to meet these targets, set by the National Forest Policy.

The February 2024 interim Supreme Court order effectively overrode the FCAA and ordered union, state and union territory (UT) governments to follow the “broad and all-encompassing” definition of forests as established by its 1996 judgment in the Godavarman case.

Over the last 15 years, India has cleared 300,000 hectares of forest or 3,000 sq km, equivalent to more than twice the area of Delhi, for everything from mining to hydel projects to cloth factories.

Despite its obvious flaws, the land component of compensatory afforestation provided some semblance of regaining forest land for effective conservation, if native forests were scientifically restored.

The MoEFCC instead allowed existing forests for use in compensatory afforestation in what is obviously deliberate defiance, passing the FCAA 10 days after the Supreme Court February 2024 order, which disallows existing forests to ‘compensate’ for those that are cleared.

The 2024 order implies that all forests would follow the “dictionary meaning”, regardless of ownership or status and any proposal to clear forests would need to get legal clearance.

Understanding Forests

The 2024 Supreme Court order, in effect, mandates that any forest land, including unidentified forests, revenue forests, unclassed forests and deemed forests, covered under the Godavarman order, must be protected and cannot be used for compensatory afforestation.

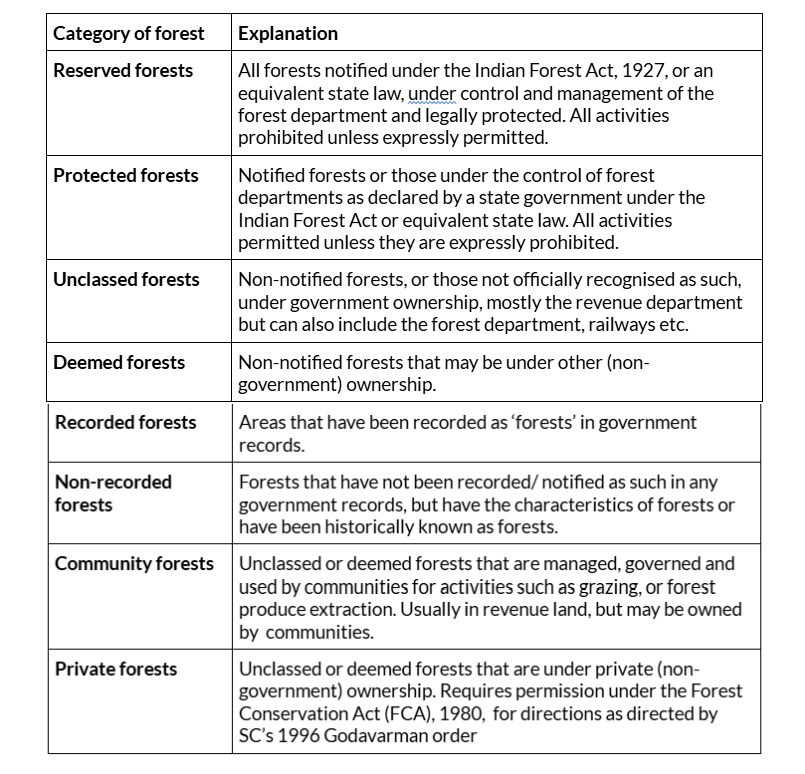

Here is an explanation of these categories of forests:

Note: All unclassed forests, deemed forests, non- recorded forests, community and private forests should have been identified and brought under the purview of the FCA (as per the Supreme Court’s Godavarman order), which implies that they cannot be used for compensatory afforestation, according to Supreme Court’s February 2024 interim order.

Following the Supreme Court’s orders, in March 2024, the union environment ministry wrote to all states and UTs directing them to “act strictly in accordance” with the court order and follow it in “letter and spirit”.

Defying The Supreme Court

Despite the law, as it has evolved, the union environment ministry and its regional offices have continued diversions of forests—in disregard to the SC’s 1996 Godavarman judgement, the interim order in the 2024 FCAA case and its own March 2024 directive.

Forests that ought to be protected by these court orders are being handed over by a deliberate misinterpretation and misapplication of laws and rules, particularly those concerning compensatory afforestation, according to our analysis.

A basic principle of compensatory afforestation is that the company or user agency must provide an equivalent area of non-forest land in lieu of the forests that will be cleared and pay for its afforestation.

Any forest land—including unclassed forest areas covered under the Godavarman order—cannot be used for compensatory afforestation, according to the 2024 Supreme Court order.

Yet, the government is allowing just this.

Our analysis of the minutes of 26 meetings of the forest advisory committee (FAC)—constituted by the ministry to vet forest-diversion proposals—and REC meetings since the passing of the interim Supreme Court order till 30 September 2024 reveals recurring breaches.

Money For Forests, Land For Free

We found that 87 proposals for forest diversion were considered by both the FAC and the RECs between 19 February and 30 September, 2024.

- In 26.8% (15 cases) clearances were given by allowing afforestation or money for afforestation on degraded forest lands. For example, degraded forests would be afforested to compensate for cutting nearly 27.8 hectares of forest for a highway in Sikkim, without providing non-forest land, as the compensatory-afforestation law requires.

- In 15 cases (26.8%), forests were handed over by accepting unclassed forests as compensatory afforestation. Unclassed forests qualify as forests and so cannot be used as land for compensation, according to the Supreme Court’s Godavarman and 2024 orders. Yet, Bhubaneswar’s REC on 29 August 2024 approved the clearance of 12.7 hectares of forest, prime elephant habitat, for a railway flyover in Jharsuguda, Odisha. Degraded revenue forest land of 25.91 was offered as ‘compensation’ for afforestation, though as per law, it should have been protected.

- In 29% (17 cases) no land was proposed for compensatory afforestation, yet clearances to cut forests were granted, suggesting that compensatory afforestation could be ignored.

- In 30% (17 cases), the FAC and REC granted retroactive clearances to projects that had already violated the law, the FCA and ignored the SC’s order against post-facto approvals.

The project proposals we analysed were cleared despite multiple violations, including a breach of forest laws.

For instance, the FAC cleared cutting 4.7 hectares of forest to construct a road in Shimla district, Himachal Pradesh, even though the agency had already started construction without approval under the FCA. The compensatory afforestation proposed involved only afforesting 9.5 hectares of degraded forests, with no compensation through non-forest land provided by the user agency.

What is clearly evident in our analysis is that the union environment ministry obfuscates compensatory afforestation compliance by categorising non-notified unclassed/revenue forests as non-forest lands, a misrepresentation, as these are forests as per the Godavarman order.

The petitioners, including 11 former civil servants and two conservationists, of the FCAA case—hearings of which continue in the Supreme Court after its February 2024 order—wrote in October 2024 to the MoEFCC on 19 October 2024, pointing out the violations of the Supreme Court orders and requested corrective measures.

The MoEFCC has not yet responded, according to the petitioners.

Forests Have Grown: Govt

For decades now, compensatory afforestation has been touted by the government as the panacea to apprehensions about growing deforestation and shrinking forests nationwide.

India is ranked second in deforestation levels globally and lost 6,684 sq km—equivalent to nearly twice the size of Goa—of forests, according to a September 2024 report by a UK-based business energy comparison service.

One of the government’s main lines of defence to justify the clearing of forests is that the company or agency involved provides non-forest area to replace the forest being cleared and pays for afforesting it, a process that increases India’s forest area.

Environment and forest minister Bhupendra Yadav told Parliament on 8 August 2024 that even though India had lost 1,734 sq km of forests to “development” over the past 10 years, compensatory afforestation increased forest area by 21,762 sq km between 2011-21.

Yadav's claim would not be correct if forests are used for compensatory afforestation because not only are the cleared forests lost, no non-forest land is made available for compensatory afforestation. Without this land-for-land compensatory mechanism, there will be a double loss of forest, not gains as the minister claimed.

As per our calculation, 1126 hectares of non-forest lands should have been added to existing areas in lieu of diverted forests. Instead 954 hectares of forests, already counted as such in government records, are now officially new forests.

It is possible to calculate how much forest has been lost over the years to such distorted accounting of compensatory afforestation lands, if the government makes all records available.

No Shortage Of Money

Another issue made clear in our analysis is the shift in compensatory afforestation from exchanging land for land to funding afforestation, an easier proposition.

But the MoEFCC or state governments are not short of money to regenerate these ecosystems and do not require this money.

In 2004, the union environment ministry began receiving what are called Compensatory Afforestation and Fund Management and Planning Authority or CAMPA funds, deposited by companies or agencies cleared to cut forests.

These funds were meant to finance compensatory afforestation and allied activities, such as protection and regeneration of forests, wildlife protection and management, and related activities. As of March 2023, Rs 32,534 crore or 60% of CAMPA funds were not used.

Indeed, the government’s auditor, the Comptroller and Auditor General, has criticised governments for misusing CAMPA funds (here, and here) for, among other things, construction projects, infrastructure development, cars, teak plantations and research.

The FCA Slowed Forest Loss

Before the FCA became law 34 years ago in 1980, states could cut forests with no checks.

Over three decades to 1980, about 45 lakh hectares of natural forests—more than the area of Haryana—were cleared for “non-forestry purposes”, to use official jargon.

That meant 150,000 hectares of forests were cut every year. After the FCA, clearing of forests declined to 38,000 hectares annually.

However, forests which were not notified or were run by agencies other than forest departments, such as revenue departments and private forests, continued to be cleared without oversight.

The Supreme Court addressed this lacunae in its 1996 Godavarman directive, which said that all forests, irrespective of ownership and status, would be governed by the FCA. The court asked all states and UTs to create state expert committees (SECs) to “identify all forests as per dictionary meaning, irrespective of ownership” that would be granted legal protection.

This order saw poor compliance. SEC reports were only made public after the Supreme Court ordered it in February 2024. The reports were mostly superficial without details or verifiable data of unclassed, deemed, non-notified and non-identified forests.

The MoEFCC and States also failed to comply with the Supreme Court’s 2011 Lafarge order, which ordered states and the Forest Survey of India to publish “geo-referenced district forest maps containing the details of the location and boundary of each plot of land that may be defined as ‘forest’ for the purpose of the FCA”.

‘Land for Land & Tree for Tree’

The FCA emphasises a “land-for-land-and-tree-for-tree” principle, reiterated in the December 2023 FCAA consolidated guidelines, which state that any diversion of forests must be compensated by replacing it with equivalent non-forest land, with companies or agencies involved required to pay a “net present value” based on a monetary valuation of the forest to be cut.

But several clauses in another set of FCAA Rules, issued on 29 November 2023, allow forests to be cut without following the land-for-land-and-forest-for-forest requirement. These are:

- Allowing the use of degraded and unclassed forests for land compensation or only paying for afforestation.

- Exempting union and state government agencies, especially public sector undertakings, mining coal from providing equivalent non-forest land for compensatory afforestation or only paying for afforesting degraded forest land if non-forest land is unavailable.

- Allowing easier, rapid diversions by allowing forest departments to identify unclassed forests or revenue forests or those under ownership of the revenue department for the user agency to provide as compensatory afforestation, if non-forest land provided is found unsuitable or is unavailable. Such ‘land banks’ would be usually zudpi or scrub forests in Maharashtra, chote bade jhad ka jungle (forest of large-small trees) classified as revenue forests in Haryana and Punjab. But these are forests as per the Godavarman order. This clause contradicts the environment ministry’s own 2007 affirmation that zudpi forests, chote bade jhad ka jungle are deemed forests under the Godavarman order.

- Exempting renewals of mining leases from fulfilling compensatory afforestation requirements, if they have done so in the initial diversion. This ignores the cumulative impact of mining and is against the principle that all forest impacts should be offset. To illustrate, the FAC on 27 August 2024 allowed the Cement Corporation of India Limited to renew a 172-hectare mining lease in Himachal’s Paonta forest division. The initial 20-year approval lapsed in 2019, with violations recorded, but the FAC asked for no compensatory afforestation since it was done in 1999.

This means that forests leased for mining for a certain period never return to the forest department.

More Harm Than Good

While compensatory afforestation should—in principle—counterbalance forest land lost to development, the FCAA of 2023 allows compliance by providing forests already in government ownership through an array of unclassed or degraded forest lands, including revenue forests and specific ecosystems nationwide.

Many of these areas are ecologically sensitive, with high biodiversity value. Zudpi forests, for instance, support leopards, bears, pangolins, wolves and bustards—all protected as Schedule I species under the Wildlife Protection Act 1972—among other endangered species.

These areas serve as critical corridors for megafauna, such as tigers and elephants. Redefining these areas as expendable "land banks" for afforestation destroys wildlife habitat and affects species survival.

These provisions under the 2023 FCAA rules allow a “double loss” of forests, reflecting a trend of circumventing laws to speed up forest clearances for “ease of doing business” with potentially irreversible impacts on 197,159 sq km or 27% of forests that do not have legal protection because of the government’s failure to comply with the Godavarman and the Lafarge orders.

This figure is a guesstimate in the absence of digital maps showing the geographical locations of forests, since the SEC reports do not provide data on the extent and location of unclassed forests. In the absence of either it is not possible to gauge forest loss. Forest Survey of India reports do not provide this information—because the Lafarge order has not been implemented.

(Prakriti Srivastava is a former principal chief conservator of forests, Kerala, and a former deputy inspector general for wildlife in the union environment ministry. Prerna Singh Bindra is a former member of the National Board for Wildlife. Krithika Sampath is a conservation researcher.)

Get exclusive access to new databases, expert analyses, weekly newsletters, book excerpts and new ideas on democracy, law and society in India. Subscribe to Article 14.