Lucknow: Omprakash Gupta, 53, a farmer and resident of the Todi-Fatehpur gram panchayat in Jhansi district, in the arid Bundelkhand region bordering Madhya Pradesh, died by suicide on 24 July 2021.

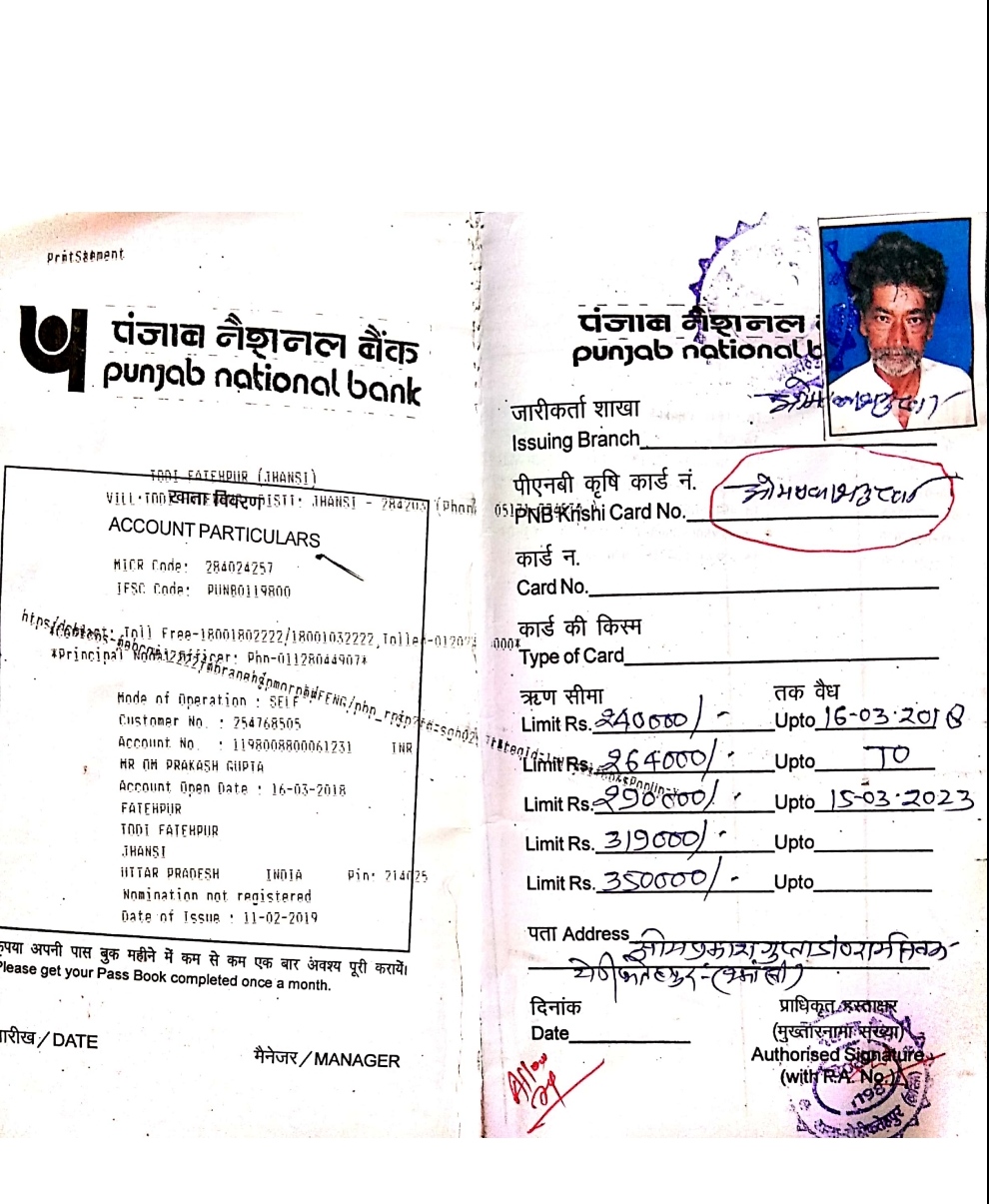

The family owns three hectares of farm land, his son Anil told Article 14. His father had availed a loan of Rs 300,000 from Punjab National Bank’s branch in their village, a crop loan offered to holders of Kisan Credit Cards, on 16 March 2018, for his kharif crop.

[[https://tribe.article-14.com/uploads/2021/10-October/27-Wed/UPCrop3.jpg]]

Gupta also paid the premium for the Pradhan Mantri Fasal Bima Yojana (PMFBY) for 2018, 2019 and 2020—farmers who take loans must compulsorily sign up. The PMFBY was launched in 2016 to provide farmers an affordable crop insurance product that would cover risks from pre-sowing to post-harvest stage.

Farmers in the Bundelkhand region have suffered three consecutive years of crop loss on account of drought and heavy rains.

“But my father did not receive an insurance payout for even a single year,” said Anil, who is in his late thirties. If their claim had been accepted at least one year, about Rs 150,000 he estimated, a large part of their debt could have been repaid. “My father would have been alive today," he said.

[[https://tribe.article-14.com/uploads/2021/10-October/27-Wed/UPCrop8.jpg]]

For Gupta’s younger daughter’s wedding in June 2019, he took a handful of small loans, this time from villagers, said Krishna Murari, Gupta’s nephew.

Villagers in Todi-Fatehpur said they understood Gupta’s pain, for almost every farmer in the village had had similar experiences. None of his creditors in the village ever demanded that the money be repaid.

“But he was very unhappy and disheartened because of not being able to repay the loans,” said Murari. The crop insurance companies showed no interest in resolving the matter, he claimed. “They are just making profits from the crop insurance premium paid by poor farmers like us."

[[https://tribe.article-14.com/uploads/2021/10-October/27-Wed/UPCrop7%20%281%29.jpg]]

Majboot Singh, 60, of Bhalonilodh village in Lalitpur, another district of Bundelkhand, registered for the crop insurance scheme from the nearby Jan Seva Kendra on 25 July 2020, to risk-proof his kharif crop. He deposited a premium of Rs 7,800 for his 9.75-hectare farm.

Singh planted urad, or black gram, but his crop was destroyed, first by a storm and then by continuing rain. Singh informed the district magistrate of Lalitpur, logged into the PMFBY portal and posted information about the losses. He contacted the head office of the private insurance company and told them his entire crop was gone.

Speaking to Article 14 in July 2021, Singh said that a company surveyor took his documents and photos of the destroyed urad crop. The then Lalitpur district manager for the insurance company had told him that he could expect the claim to be settled.

“But due to some reason, he resigned. A new manager told me verbally after assuming charge that there was a mistake in my documents and so the claim will not be accepted,” said Singh.

The farmer asked the manager to issue a letter documenting this, and also to refund his premium. “I asked him how the insurance premium had been deducted when there was a discrepancy in my papers. But officials at the company are not ready to listen to me,” he said.

He estimated that his payout would have been Rs 321,000, a sum that would have provided relief amid continuing financial distress. “This year again my crop has been damaged due to untimely rains,” Singh said.

Launched in February 2016, the PMFBY is a compulsory risk cover for all farmers who avail a seasonal crop loan, while non-loanee farmers may also seek to be covered under the scheme, which covers different types of risks ranging from natural calamities and pest attacks to post-harvest losses.

Despite the risk cover, several hundred farmers in the Bundelkhand region ended their lives over the past three years, many frustrated by the long delays in settling insurance claims. In Jhansi district alone, more than 49,000 farmers have pending claims under the PMFBY for the kharif 2019 season.

According to farmers, those already in debt due to an illness or marriage in the family who then also take a crop loan are unable to withstand the twin blows of a crop failure and rejection of their crop insurance claims.

Farmer activist Pushpendra Pathak, who is based in Jhansi, said most of the hundreds of farmers who died by suicide in the Bundelkhand region had debts running into a few lakh rupees.

Pathak himself has a Rs 350,000 loan on his Kisan Credit Card, and a slightly smaller sum loaned from a moneylender. “When a crop fails, we still need money to maintain the family, preparations to cultivate the next crop, electricity bill used for irrigation, and for any emergency,” said Pathak. “That is why farmers have to take loans from moneylenders."

If insurance claims were settled as a matter of course, then a large number of farmer suicides can be prevented, he said.

Asked about the pending crop insurance claims, UP’s agriculture minister Surya Pratap Shahi told Article 14, "Where did you get this data? If you say a certain someone has dues, we can't give them dues just like that.”

Shahi said that a committee investigates farmers’ insurance claims: “If your car is insured and if there is no accident, then the claim will not be accepted, right?” Only if crop damage has occurred, and if the cases fall within the norms and guidelines of the scheme can claims be settled, he said.

About the pending claims of farmers of Jhansi, the minister said: “The matter is not pending.” He said data had not been uploaded on the portal within the stipulated time, and therefore claims were rejected.

The problem of pending claims is set against wider problems with the PMFBY, which has witnessed lower enrolment in 2021, with some states opting out on account of the premium subsidy to be borne by them.

The Uttar Pradesh government, however, has attempted to draw more farmers into the showcase scheme. This is despite the relatively low percentage of insured farmers receiving payouts—about 962,000 out of 3.9 million insured for the kharif 2016 season; 401,000 out of 2.58 million in the kharif 2017 season; 569,000 out of 3.16 million in the kharif 2018 season and 595,000 out of 2.38 million in the kharif 2019 season.

Across the country, according to the government’s reply to a question in Rajya Sabha, between 2018-19 and 2019-20, rejection of claims rose by 900%.

‘Suicides Not Due To Debt, Insurance Claim Rejection’

The local administration in Bundelkhand denied that the suicides were due to debt or due to insurance claims being rejected.

Sub-divisional magistrate Rajkumar said most unwell persons have an outstanding loan, and the death of such persons is often interpreted as being on account of Kisan Credit Card (KCC) debt.

About Omprakash Gupta of Jhansi, the SDM said: "He was a chronic drinker, he had his own family problems, that's why he committed suicide."

On being told that Gupta had been burdened with debt, the officer said, “90% of farmers have the KCC, does that mean everyone is committing suicide? If he had declared that this was the reason, then it would have been a different thing, otherwise how is one to believe this?”

He said the administration could only be aware of such a problem if the person had brought to their notice his financial situation.

Pass The Buck: Insurers Blame Banks For Delays

Responding to a query on pending claims, Shiv Shankar, divisional manager for the National Insurance Company Ltd, which provided the crop insurance product in Jhansi during the 2019-2020 season, said banks in Jhansi had not supplied to them the correct data on the PMFBY portal for thousands of farmers.

Shankar said that 16,411 cases are pending with the union ministry of agriculture and farmers welfare.

In another 32,727 pending cases, the insurance premium for the kharif 2019 season had been returned to the banks, he said, indicating that the risk cover had not been granted or had been cancelled.

“Now the banks are asking these farmers to seek claims from the insurance company... We told the farmers that it is the responsibility of the banks to give the claim. They can go to the court, make us a party, the bank should give its answer and we will present our side. Whoever the court orders will pay the claim,” he said.

The bank’s statement contradicted the insurer’s.

Data from the office of the deputy director for agriculture in Jhansi district showed that of 32,727 pending insurance claims, 30,823 are account holders at Punjab National Bank.

According to lead district manager Arun Kumar of Punjab National Bank, the premium amount in 30,823 pending cases of Punjab National Bank account holders was returned to the farmers’ accounts. “This issue came up in 2019 when the insurance company suddenly made Aadhaar cards mandatory,” he said.

The data of a large number of farmers did not match their Aadhar card details, due to which their insurance was “cancelled”, according to Arun Kumar. “Farmers are not literate, so they are facing problems in getting Aadhaar corrected,” he said. “Gradually the situation will be streamlined and farmers will then not face any problem."

He did not comment on whether these 30,823 farmers had been informed upon registering claims that their insurance had in fact been cancelled owing to technical glitches.

Farmers told Article 14 that while they made the rounds of various offices for more than a year seeking settlement of their claims, neither the bank nor the insurer informed them that the premia would be returned to them as their insurance stood cancelled.

How Crop Insurance Works

At the beginning of every crop season, the premium for the PMFBY is deducted from the farmer’s loan account and is paid to the private insurer. The PMFBY comes with a state subsidy, and this amount, contributed by the state and central governments, is also paid to the insurance company.

For example, in the 2019 kharif season, a total premium of Rs 719 crore was paid for 2.3 million farmers in Uttar Pradesh. This included farmers’ premium that totalled up to Rs 159 crore and Rs 280 crore paid by the state government, and a matching sum by the central government.

Four conditions were applicable for insurance claims. The first was 'failed sowing'—if 75% of the sown area in a given area fails to germinate due to moisture stress or excess rain, the insurance company will pay 25% of the farmer's cost.

The second condition was 'mid season adversity'—if a crop was affected by insects at the time of flowering, or if flowers were destroyed for any other reason, the insurance company will pay 25% of the cost to the farmer if 51% or more is damaged, on the basis of 'tentative yield' of harvest.

The third condition was 'localised claim'—if a farmer informed the insurance company on the toll-free number provided, within 72 hours in case of sudden lightning, water logging, hailstorm or landslide that damaged a ready crop, and if the bank informed the insurance company within a week.

The fourth condition was 'post harvest' damage— if harvested produce lying on the field is damaged by rain or cyclone or a fire arising out of natural causes, and if the farmer informed the insurance company within 72 hours.

In case of situations three or four, the insurance company would survey the crop in the presence of state government employees and employees of the insurance company. A 'tentative yield' would be fixed and the insurance company would pay the claim, through the bank.

Complaints or disputes with the insurance company are to be resolved by the state government and, in cases where the matter remains unresolved, the state government is tasked with informing the union ministry of agriculture and farmers welfare.

‘No Pending Case’: Officials Deny Data

According to the data provided by Rajesh Kumar Gupta, state director for agricultural statistics & crop insurance, 2.3 million farmers were insured, with a sum insured of Rs 7,968.75 crore.

Claim payouts were made to only 628,841 farmers, who received a total of Rs 814 crore.

According to UP’s deputy director for agriculture Uma Shankar, all pending payments of crop insurance claims were cleared until the kharif 2020 season. “Now there is no pending case,” he said. According to him, some farmers had paid an insurance premium to two different banks for the same farm land, with the same Aadhar. “Such cases cannot be called pending,” he said.

Krishna Murari Gupta, the nephew of the late Omprakash Gupta of Jhansi who ended his life in July, refuted the claim of the government. He said his uncle only deposited the premium with the Punjab National Bank, with his Aadhaar card details. “But the insurance claim was not paid.”

In the Uttar Pradesh legislative assembly, member Ajay Kumar Lallu, also state president of the Congress party, asked a question about farmers and insurance. "Under the Fasal Bima Yojana, how many farmers were insured in the last four years and how many farmers have got compensation relative to that? Will the government compensate the remaining farmers?” He sought to know how long it would be before the farmers are compensated.

Agriculture minister Shahi gave a written reply. Eligible farmers’ claims had been settled between 2016 and 2020, he said, giving details of the number of farmers insured and the number who had received payouts. In the kharif 2019 season, of 2.3 million insured farmers, 595,000 had received payouts, his reply showed.

On compensating the remaining farmers, the minister’s reply said in Hindi, “The question doesn’t arise.”

Despite the minister’s response to the state assembly and the assurance of the deputy director for agriculture that there is no pending case, the agriculture officer of Jhansi district provided Article 14 data regarding pending payment cases.

In Jhansi district alone, 49,138 farmers have pending claims under the scheme for the kharif 2019 season.

Of 49,138 cases, 16,411 cases were pending because their details were not made available by the bank to the insurance company after rectification of data. In 32,727 cases, data was not uploaded by the banks on the PMFBY portal.

According to the lead district bank manager, of 32,727 cases, the premium amount in 30,823 pending cases was sent back to farmer's accounts in Punjab National Bank, and their insurance cover cancelled.

Regarding the 16,411 pending cases, the district director for agriculture said that in these cases, a notice has been issued by the district magistrate asking the bank to clear the payment within 15 days of farmers filing an appeal.

Notably, these were 16,411 pending cases from a single district—the number would be much higher if all of UP’s 74 districts are investigated for pending crop insurance claims.

Meanwhile, another farmer from Lalitpur, Anil Kumar, who owns a 6-acre farm, said he availed a crop loan of Rs 420,000 on his Kisan Credit Card in 2017. “The premium for the crop insurance plan is deducted every year,” he said. He received a claim payment of Rs 54,000 in 2019, but his claim was rejected in the subsequent years.

“Due to a poor harvest, I could not repay the Kisan Credit Card loan. In the midst of this tension, my daughter had to be married.” For the wedding, he took a loan of Rs 100,000 from a moneylender. “Now we are forced to live in the midst of both, the debt and the stress of crop failure.”

Lalitpur’s Singh said it is a familiar story, to see farmers end their lives in Bundelkhand. “But these insurance companies don't care," he said.

(Mohammad Sartaj Alam is an independent journalist based in Lucknow.)